|

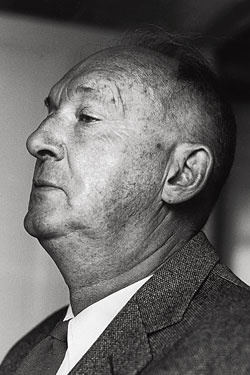

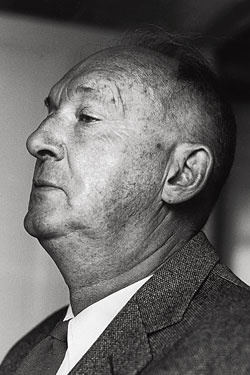

(Photo: Horst Tappe/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) |

The work of Vladimir Nabokov is an obsessive study in the risks and rewards of total control. This applies on both the micro level (his books) and the macro level (their creation). In his novels, control is often a sinister force—a tool that ends up turning on its user. Humbert Humbert controls Lolita, but the cost is that he himself is controlled by his compulsion to control her. Charles Kinbote, the unreliable pseudo-scholar at the center of Pale Fire, seizes interpretive control over a dead poet’s manuscript only to abuse it so thoroughly that his authority gradually implodes. There’s a certain irony, then, in the fact that Nabokov, as an artist, was a legendary control freak. He polished his prose all the way down to the subatomic level. “I have rewritten—often several times—every word I have ever published,” he once said. “My pencils outlast their erasers.” He mocked novelists who claimed that their characters took on lives of their own. “My characters are galley slaves,” he said. Even his interviews were scripted; he claimed (absurdly, controllingly) that his command of English, a language he had spoken since he was 4, wasn’t strong enough to allow him to speak off the cuff.

This authorial fascism yielded huge dividends—most obviously a precise linguistic razzle-dazzle that often rose to the level of Shakespeare and Joyce. Every Nabokov paragraph is a rich little stylistic Versailles: orderly cadences, exotic vocabulary, clauses nested in whimsical rows, meticulous touches of color, puzzles built out of concentric sub-puzzles, alliterative accents, perfect tropes. (One metaphor from Lolita has stuck with me for years as a model of deep simplicity: “the dandelions had changed from suns to moons.”) But this control could also be suffocating. As V. S. Naipaul once put it, “the very precision with which he gets his effects is in the long run fatiguing.” Nabokov’s wildest lyrical flights all had to be filtered through the part of his brain that liked to design chess puzzles. As a result, even his best work can leave a slightly unsettling residue: the paradoxical feeling of crazy invention fussily controlled—like the most exciting Mardi Gras of all time lavishly re-created, for a film shoot, in October, in Vancouver. His work leaves us with a nagging question: What would he have looked like with his aesthetic hair down, his literary bed unmade, his grip on the novelistic wheel slightly relaxed?

The publication of The Original of Laura, Nabokov’s very unfinished final novel, seems like a good place to start answering that question. It’s a unique chance to see the master out of control. He started writing the book in 1975 at age 76, in the midst of a late flurry of energy and ambition. (He was also assembling a book of short stories, working on the French translation of his long novel Ada, and collecting his letters and Russian poems—all while finding time for butterfly-hunting expeditions.) He hoped to finish Laura within a year; five months into the process, he estimated he was halfway done and wrote to a friend that he was having a “marvelous time.” Unfortunately, his body refused to cooperate. The last year of his life was a long tailspin of illness: pneumonia, lumbago, delirium, influenza, insomnia, fever, and various infections. As he drifted from hospital room to hospital room, and in and out of lucidity, he could see the complete book in his mind but couldn’t get it down on paper. He had to settle for reciting the finished product to (as he described it in a letter) “a small dream audience” consisting of “peacocks, pigeons, my long-dead parents, two cypresses, several young nurses crouching around, and a family doctor so old as to be almost invisible.” He died, in 1977, of fluid in his lungs.

Nabokov fully intended that his imaginary audience of birds and ghosts would be the largest group ever to enjoy Laura. Before his death, he left instructions that the manuscript should be destroyed. (Only amateurs keep drafts, he once said.) His wife, Vera—who had stopped him at least twice from burning drafts of Lolita—couldn’t bring herself to do it. Their son, Dmitri, couldn’t do it either. The manuscript sat in a Swiss bank vault for 30 years, the subject of occasional long-distance arguments over whether it should be published or burned.

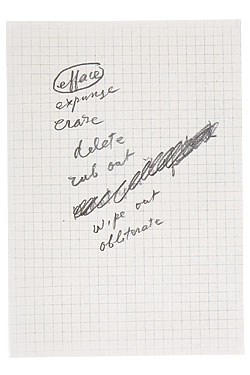

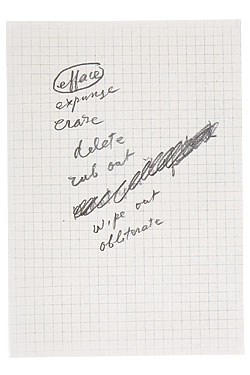

And now, finally, we have the object itself. It turns out to be an exquisite thing. Knopf has tried to bring us as close as possible to the original of The Original of Laura, and the result is a showpiece of intelligent book design built on a deep respect for the manuscript. Nabokov handwrote the book on index cards (his standard late-career practice), and all 138 of them are reproduced here, back and front, in full color, with the text transcribed underneath. The cards are even perforated, so you can punch them out and shuffle them, as Nabokov would have done as he revised. Every page contains the author’s surprising handwriting: biggish and slanted and loopy, with generous white space around his words. (I was expecting, for some reason, tiny cramped writing that colonized every available millimeter of space.) Some of the cards are heavily revised, which allows us to see, for the first time, the work of Nabokov’s famous eraser: fuzzy little storm clouds of smudged graphite loom behind neatly rewritten words. It’s a fascinating read on many levels. If Knopf were to publish a series of painstakingly reproduced Nabokov manuscripts, I’d pawn my Kindle to buy them all.

|

A fragment of Nabokov's last manuscript.

(Photo: Courtesy of Knopf) |

The Original of Laura is a glorious mess. It tells the story—or begins to attempt to tell the story—of two main characters: a 24-year-old petulant beauty named Flora and her rotund older husband, the famous neurologist Philip Wild. Flora enters the novel in a burst of pure attitude, sleeping with a lover after a party, on someone else’s bed, her fur coat spread out “with comic fastidiousness” underneath her. (She uses the tender post-coital moments to call another lover and cruelly break up with him.) When she returns to her villa, we get a vintage Nabokovian micro-scene. Flora’s fat husband appears “walking a striped cat on an overlong leash.” (“The scene might be called somewhat incongrous,” Nabokov writes—one of the subdermal pleasures of reading Laura is watching the great perfectionist persistently misspell words.) As Flora heads for the front door, her husband picks up the cat and follows, and the episode ends with an odd, trivial detail that adds a tiny flare of joy to an otherwise miserable scene: “The animal seemed naïvely fascinated by the snake trailing behind on the ground.”

Flora has a depressing backstory: a photographer father who commits suicide after discovering “that the boy he loved had strangled another, unattainable boy whom he loved even more”; a ballerina mother who sells the father’s self-portraits of his suicide to a tabloid, then takes up with a creepy older lover whose improbable name, “no doubt assumed,” is Hubert H. Hubert. (He tries to feel up Flora one day; she kicks him in the crotch; her mother scolds her.) The upshot of all of this is a life of casual and joyless promiscuity. Flora is a shadowy, unfinished character, which seems to be at least partly by design: “Everything about her is bound to remain blurry.”

Flora’s husband is a famous lecturer whose body—like Nabokov’s—is failing him: He has chronically painful feet and a “humiliating stomack ailment” (“I loathe my belly, that trunkful of bowels”). He spends most of his time conducting radical experiments in what he calls “auto-dissolution,” an ecstatic process in which he puts himself into “hypnotrances” and flirts with death by mentally making parts of his body disappear. “By now I have died up to my navel some fifty times in less than three years,” the professor writes in a manuscript about his experiments.

Wild’s manuscript is one of two books hidden inside The Original of Laura. The other is a best-selling novel called My Laura, written about Flora by one of her ex-lovers. (This makes Flora “the original of Laura.”) Wild declares it “a maddening masterpiece”; Flora buys a copy but just sits with it, hesitating to read.

Was Nabokov right to want his Laura destroyed? I’m still undecided about the ethics of its publication. (In his gratingly arrogant introduction—about which probably the less said the better—Dmitri Nabokov offers no real justification for his decision.) But from a purely selfish standpoint, as a reader holding the book in my hands, I’m glad Nabokov was overruled. Laura offers just enough of the familiar Nabokovian pleasures to be enjoyable as a straightforward read: style, invention, humor (“I strongly object to the bipedal condition”), occasional sprays of archaic vocabulary (inguen, nates, hallux, omoplates, volupty). But its deepest pleasure is the one Nabokov wanted us never to have: a peek at the imperfect, ordering intelligence behind all of his finished products. This glimpse shouldn’t hurt his reputation; if anything, it should help. It’s like seeing an unfinished Michelangelo sculpture—one of those rough, half-formed giants straining to step out of its marble block. It’s even more powerful, to a different part of the brain, than the polish of a David or a Lolita. It humanizes the perfection. Laura helps us to imagine, more concretely, the labor behind the rest of Nabokov’s labor-intensive masterpieces. His index cards are precise, incremental—a paragraph here, an obsessively revised image there—the exact opposite of, say, Kerouac’s giant On the Road scroll. It’s fun to watch the systems and subsystems organize themselves and begin to cohere. (He uses an entertainingly wide variety of little tags to keep his cards in order: numbers, letters, Xs, circles progressively filling with lines.) Nabokov’s published polish is so familiar, so thick, that the eye almost bounces off it. To see him rough is to see him new.

In his introduction, Dmitri calls the book an “embryonic masterpiece.” Unfortunately, it’s too embryonic to make that kind of judgment with any confidence—it could just as easily be an embryonic minor work. If it is a masterpiece, I’d like to think it’s a more radical one than Dmitri suggests. The circumstances surrounding The Original of Laura are deeply, almost ridiculously Nabokovian. He was, after all, the Einstein of the text-life continuum, proving over and over that books and life are always intertwined. His novels are full of lost manuscripts, self-parodies, authorial stand-ins, writers who wander into their texts and tamper with characters. And it’s impossible to imagine him ever ceding control, even to death. My inner Kinbote suspects, in fact, that Laura isn’t unfinished at all—that it’s actually a perfectly executed work of literary performance art, a carefully engineered posthumous spectacle that its author spent his entire career preparing us to receive. I imagine him reaching down, even now, to crank the recursion machine harder than it’s ever been cranked. Those 30 years of drama, perhaps, were part of the work itself. He may not have even wanted the manuscript destroyed: It’s possible he wanted it read at precisely this moment, under precisely these circumstances. Incompleteness is the book’s central theme, so it could only have been finished by being left unfinished. Like Philip’s body in the midst of one of his trances, Laura survives, ecstatically, with key parts missing. It could be Nabokov’s very last brilliant joke: a black hole of textuality that he conjured and then slipped into, pulling his pencil behind him.

In the end, Philip Wild’s manuscript—the first-person account of his experiments in “self-deletion”—ends up finished but unpublished: He dies of a heart attack before his secretary gets a chance to type it up. One of Laura’s last cards suggests that a mysterious figure steals the book, intending to publish it in a different venue than Wild had planned. Nabokov’s manuscript, of course, was published, yet remains eternally unfinished. Both books, however, teach the same lesson, the orgasmic pleasures of incompleteness.