Just as Heller introduced the made up term “catch-22”, into the language, so Nabokov changed the meaning of “nymphet” from classical allusions, to one of down to earth female sexuality in contemporary society.

'Lolita' and other images: various sources. |

(CALGARY, Alberta) - The internet will probably go down in history as one of those world-changing inventions (like fire, the wheel, the printing press, the hula hoop) that changed the direction of human progress.

Surfing the web recently I came across The Guardian online website listing of The 100 greatest novels of all time

Looking at the list I was both surprised and dispirited at the small number of books on the list I had read (nine) and another 29 I had never even heard of (author or book).

For example, there is the Japanese The Tale of Genji Genji by Shikibu Murasaki. I’ve never heard of either the book or the author although that’s just Western parochialism. I got it out of the library and just couldn’t get into it. But that’s probably more about me, than about the book.

I give two examples of me. In the late 1960s my best friend at the time, Brian, (he is not my best friend today because in 1971 he was killed by a drunk driver just outside Douglas, Wyoming) enthusiastically recommended Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. I tried reading it at least five or six times before it finally “took”, and I finished it. I loved it. I recently got a copy out of the library and I’m going to try to read it again. (I say “try” because currently I have too little time and too much to read, so it may have to be put off).

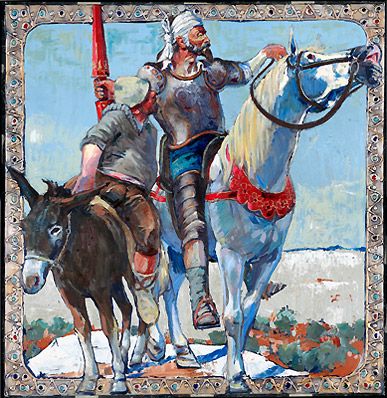

The second example is Don Quixote by the 16th century Spaniard Miguel de Cervantes. This is probably one of the more famous unread books in the world. It’s been made into a famous Broadway production Man of La Mancha with a widely popular song Impossible Dream. But the book itself? After seeing it on a Globe and Mail list as the best novel ever written, I had to give it a try. And I did, two or three times but never got very far into it.

Catch-22 did not change but, over time, I did and finally the book spoke to me. In the case of Don Quixote the book itself has changed—translated this time by Edith Grossman.

I have her version and this time it has “grabbed me”. At 940 pages, however, it is definitely not a bathtub or shower book. I expect to finish it and may, if I think it interesting enough for you, the reader, will write a report on it.

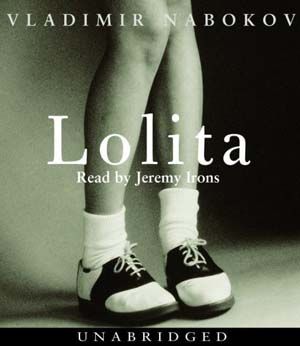

Another book on the list is Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov. Catch-22 has become an actual term in everyday discourse. Lolita, on the other hand has become, not so much an independent term, but a reference to young nymphets that most people understand in much the same way.

I never had much interest in reading Lolita but decided that I should give it a try, considering it is on the list. It turned out to be one of the strangest books I’ve ever read (and I’ve read a few).

Lolita

The book is written as a first person narrative by Humbert Humbert, a pedophile.

On the book jacket Vanity Fair is quoted: “The only convincing love story of our century.” Time called it “Intensely lyrical wildly funny.” I did find it well written—so Nabokov is a writer—but “wildly funny”? I suppose it is a matter of perspective, although while reading the book, I did smile a few times.

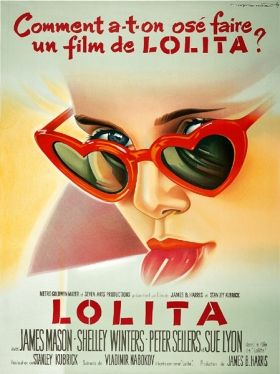

Lolita has been twice made into a movie. The first was done by Stanley Kubrick in 1962—his first independent production. (Notably: 2001: A Space Odyssey, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Full Metal Jacket, and his last film Eyes Wide Shut).

My late friend Brian and I spent the day skiing at Sunshine Village just outside of Banff and, in town that evening had steaks and beer. There was one movie theatre in town and it was showing Lolita, so we took it in. The interesting thing about the movie is that I don’t remember a single thing about it. Zip. Nada.

But, in retrospect, I discovered one interesting thing. Lolita’s mother was played by Shirley Douglas, the daughter of Tommy Douglas—the “Father” of Canada’s universal health care system. Shirley was married to Donald Sutherland and in 1972 their son, Kiefer William Fredrick Dempsey George Rufus Sutherland, star of 24, was born in London, England. (I didn’t know that people outside the Royal Family were allowed to have more than three names.)

The second movie was in 1997 with Jeremy Irons which I haven’t yet seen although I am a fan of Irons’ work. Now that I’ve read the book, I’ll make an effort to see the movie. What makes the movie more interesting to me is that the soundtrack was composed by Ennio Morricone, probably the 20th century’s greatest composer of film music—he has composed music for more than 500 movies and TV shows—probably best known for his music in the spaghetti Westerns (A Fist Full of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, etc.)

Morricone also composed the music for the 1988 movie Cinema Paradiso. I happened upon this Italian film (in Italian with subtitles) in an interesting way. In the 1997 I visited an Ennio Morricone fansite where some people had made comments. I read the comments of a man named Pat Cleary who turned out to be in Dublin, Ireland. We struck up an online friendship and he told me about CP, which I’d never heard of. I rented it and found it to be an outstanding film. When I told him this, he said I had rented the “wrong” version. I had the American release which was 121 minutes. He said I had to see the uncut version which was 155 minutes, but it was not available in Canada.

But the trust level was there and he mailed me his longer VHS copy of the movie. It was in European format, so I found a place that could translate it, then mailed his back to him.

The difference between the two cuts was like two different movies. If you’re any kind of romantic (like me) I can’t recommend it highly enough. It is the saddest, most hauntingly beautiful love story I’ve ever seen.

(Note: Lolita at the beginning of the book was 12, but there would have been problems with censors, so in the two movies, she was 14. This reminds me of a line Jim Belushi said in a movie: “You know what I like about high school girls? I get older, they stay the same age”.)

Back to Lolita. When I read a book I always read the Forewords, Prefaces and Introductions. In this case I broke my own rule and did not read Martin Amis’ Introduction until after.

Amis points out that it is well known that in real life, Nabokov was a “kind man” but that “Lolita is a cruel book about cruelty,” and that “Nabokov is the laureate of cruelty”.

As narrator, Humbert Humbert says his story begins with Annabel, a childhood friend who was only a few months younger.

“At first, Annabel and I talked of peripheral affairs. She kept lifting handfuls of fine sand and letting it pour through her fingers. Our brains were turned the way those of intelligent European preadolescents were in our day and set, and I doubt if much individual genius should be assigned to our interest in the plurality of inhabited worlds, competitive tennis, infinity, solipsism and so on. The softness and fragility of baby animals caused us the same intense pain. She wanted to be a nurse in some famished Asiatic country. I wanted to be a famous spy.

“All at once we were madly, clumsily, shamelessly, agonizingly, in love with each other; hopelessly, I should add, because that frenzy of mutual possession might have been assuaged only by our actually imbibing and assimilating every particle of each other’s soul and flesh; but there we were unable to mate as slum children would have easily found an opportunity to do….The only privacy we were allowed was to be out of earshot but not out of sight….There, on the soft sand, a few feet away from our elders, we would sprawl all morning, in a petrified paroxysm of desire, and take advantage of every blessed quirk in space and time to touch each other.”

Those 211 words tell me two things; first that Nabokov really is a gifted writer; and, second, that fundamentally, Humbert Humbert is not a bad or evil person. As Amis writes: “However cruel Humbert is to Lolita, Nabokov is crueller to Humbert—finessingly cruel”.

Four months after that frustrating summer, Annabel dies of typhus. “Long after her death I felt her thoughts floating through mine”.

“I leaf again and again through those miserable memories, and keep asking myself, was it then, in the glitter of that remote summer, that the rift in my life began…”

Later:

“While a college student, in London and Paris, paid ladies sufficed me. My studies were meticulous and intense, although not particularly fruitful. At first, I planned to take a degree in psychiatry as many manqué talents do; but I was even more manqué than that; a peculiar exhaustion, I am so oppressed, doctor, set in; and I switched to English literature, where so many frustrated poets end as pipe-smoking teachers in tweeds”.

Just as Heller introduced the made up term “catch-22”, into the language, so Nabokov changed the meaning of “nymphet” from classical allusions, to one of down to earth female sexuality in contemporary society. He defines a nymphet:

“”Between the age limits of nine and fourteen there occur maidens who, to certain bewitched travellers, twice or many times older than they, reveal their true nature which is not human, but nymphic (that is, demoniac); and these chosen “creatures I propose to designate as ‘nymphets’”.

“Between those age limits, are all girl-children nymphets? Of course not. Otherwise, we who are in the know, we lone voyagers, we nympholepts would have long gone insane. Neither are good looks any criterion; and vulgarity, or at least what a given community terms so, does not necessarily impair certain mysterious characteristics, the fey grace, the elusive, shifty, soul-shattering, insidious charm that separates the nymphet from such coevals of hers as are incomparably more dependent on the spatial world of synchronous phenomena than on that intangible island of entranced time where Lolita plays with her likes. Within the same age limits the number of true nymphets is strikingly inferior to that of provisionally plain, or just nice, or ‘cute,’ or even ‘sweet’ and ‘attractive,’ ordinary, plumpish, formless, cold-skinned, essentially human little girls…”

And so the story of Humbert Humbert begins. I am reminded of something written in the 1950s by the manqué writer Gerald Kersh: “There are men whom one hates until a certain moment when one sees, through a chink in their armour, the writhing of something nailed down and in torment”. Nabokov gives us this insight into Humbert—a man in torment.

Lolita, the book, clearly exists on several levels—most of which I missed on the first reading. I don’t know that I’ll read it again because I have gotten to that stage in my life where (I used to joke, but no longer): So many books, so little time.

============================================

Daniel Johnson was born near the midpoint of the twentieth century in Calgary, Alberta. In his teens he knew he was going to be a writer, which is why he was one of only a handful of boys in his high school typing class — a skill he knew was going to be necessary. He defines himself as a social reformer, not a left winger, the latter being an ideological label which, he says, is why he is not an ideologue. From 1975 to 1981 he was reporter, photographer, then editor of the weekly Airdrie Echo. For more than ten years after that he worked with Peter C. Newman, Canada’s top business writer (notably on a series of books, The Canadian Establishment). Through this period Daniel also did some national radio and TV broadcasting. He gave up journalism in the early 1980s because he had no interest in being a hack writer for the mainstream media and became a software developer and programmer. He retired from computers last year and is now back to doing what he loves — writing and trying to make the world a better place

Daniel Johnson was born near the midpoint of the twentieth century in Calgary, Alberta. In his teens he knew he was going to be a writer, which is why he was one of only a handful of boys in his high school typing class — a skill he knew was going to be necessary. He defines himself as a social reformer, not a left winger, the latter being an ideological label which, he says, is why he is not an ideologue. From 1975 to 1981 he was reporter, photographer, then editor of the weekly Airdrie Echo. For more than ten years after that he worked with Peter C. Newman, Canada’s top business writer (notably on a series of books, The Canadian Establishment). Through this period Daniel also did some national radio and TV broadcasting. He gave up journalism in the early 1980s because he had no interest in being a hack writer for the mainstream media and became a software developer and programmer. He retired from computers last year and is now back to doing what he loves — writing and trying to make the world a better place