Download PDF of Number 19 (Fall 1987) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 19 Fall 1987

_________________________________________

CONTENTS

News by Stephen Jan Parker 4

Nabokov at the Bakhmeteff

by Zoran Kuzmanovich 12

Emigré Responses to Nabokov (III): 1936-1939

by Brian Boyd 23

Nabokov in the USSR (Continued)

by Stephen Jan Parker 39

Annotations & Queries by Charles Nicol

Contributors: Robert Grossmith, Gene Barabtarlo,

Gerard de Vries 46

Abstract: Daniele Souton, "Vladimir Nabokov's

Machineries, The Dynamic Interplay of Discourse

and Story in Three of his Novels" 59

1986 Nabokov Bibliography by Stephen Jan Parker 61

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 19, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

[4]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

The 1987 Nabokov Society meetings will be held this year in San Francisco. Two sessions will be held in conjunction with MLA on December 27 in the Shasta Room of the San Francisco Hilton. The first - "Nabokov, Philosophy, and the Arts" — will meet at 7:00 pm. It will be chaired by Leona Toker (Hebrew University, Jerusalem) with participation by Zoran Kuzmanovich (University of Wisconsin, Madison), Leona Toker, and Ellen Pifer (University of Delaware). The second session — "The Posthumous Nabokov" — which follows will be chaired by Samuel Schuman (Guilford College). Participants will be Kim McMullen and D. Barton Johnson (both of the University of California, Santa Barbara) and Sam Schuman. The Society's business meeting will follow the formal programs. The main item on the agenda will be the election of new officers.

The Nabokov Society session in conjunction with AATSEEL - "Authorship and Authority: Nabokov's Artistic Control" - will be held 3:15-5:15, Tuesday, December 29, at the Westin St. Francis Hotel (on Union Square). Susan Elizabeth Sweeney (Brown University) will serve as Chair and John Kopper (Dartmouth College) as Secretary. Participants include Charles Nicol (Indiana State University), Galya Diment (University of California-Davis), Brenda Marshall (University of Massachusetts-Amherst), Martha Carpenter (Santa Rosa Junior College), and Phyllis Roth (Skidmore College) as discussant.

[5]

At 1:15 on Monday, December 28, at the AATSEEL session on "Memoir and Autobiographical Literature," Priscilla Meyer will present a paper entitled "Nabokov's Pale Fire as Memoir."

*

The following list of VN works received March - September has been provided by Mrs. Vera Nabokov:

March — Dreams, selected by Stephen Brook. NY: Oxford University Press; with four dreams by VN.

March — A Guide to Berlin & Other Stories. Tokyo: Kenkyusha; four stories by VN in English and Japanese.

March — Détails d'un Coucher de Soleil [Details of a Sunset], tr. Maurice and Yvonne Couturier and Vladimir Sikorskky. Paris: Julliard, Presses Pocket edition.

April — "Frühling in Fialta" [Spring in Fialta]. In Manfred Kluge. Das Frühlings Lesebuch. Munich: Wilhelm Heyne.

April — "The Admiralty Spire," The Defense , "A Fairy Tale". In Bernd Eilert, ed. Das Hausbuch der Literarischen Hochkomik. Zurich: Haffmans.

April — "A Day Like Any Other" [poem] . In Morag Styles. You'll Love This Stuff. New York: Cambridge University Press.

May— Pnin, tr. Else Hoog. Amsterdam: Uit. de Arbeiderspers.

[6]

May — "The Passenger." In Enjoying Stories. New York: Longman.

May — Lolita. Paris: Gallimard, Folio reprint.

May — "Terra Incognita." In Das Ferien-Lesebuch 1987. Munich: Wilhelm Heyne.

June — Selection from Glory. In Geschichten aus der Provence. Munich: Wilhelm Heyne.

June — Omago [The Enchanter] , tr. Jorio Dauster. Rio de Janeiro: Editors Nove Fronteira.

June — "On How to Be a Good Reader" and "The Vane Sisters". In The Bedford Introduction to Literature. New York: St Martin's Press.

June — Ada O L’Ardor, tr. Jordi Arbones. Barcelona: Edicions 62, Catalan edition.

July — Fortrylleren [The Enchanter], tr. Johannes Riis. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

July — El Hechicero [The Enchanter], tr. Rolando Costa Picazo. Buenos Aires: Emece Editores.

August — Der Zauberer [The Enchanter], tr. Dieter Zimmer. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

August — Speak, Memory. Harmondsworth: Penguin reprint.

September — Lolita, tr. Josep Daurella. Barcelona: Edhasa, Catelan edition.

[7]

September — Autres Rivages [Speak, Memory], tr. Yvonne Davet. Paris: Gallimard, second printing.

September —"Le Dragon," tr. V. Sikorsky. First French publication of the Russian story, "Drakon." In Le Journal Littéraire, no. 1 (15 September-15 November).

*

From Michael Juliar: Though out barely a year, there is no question that my Vladimir Nabokov: A Descriptive Bibliography (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1986) already needs updating. Fellow bibliographers, knowledgeable book hunters, and patient proofreaders from around the world have sent me their findings. The Nabokovian has published corrections and findings of newly discovered Nabokov publications. I have double-backed on my bibliographic trails and have uncovered an assortment of mistakes, some quite embarrassing. I have also been tracking Nabokov works published posthumously during the last year and a half.

The update is too long for one issue of The Nabokovian. I will send a Xerox of it — some 26 pages — to you or your institution at cost. For recipients in the U.S., Canada, or Mexico, that's $4.00, for those in South America or Europe, $5.00, and for the Far East, $6.00. I can make this offer only for three months after you receive your copy of The Nabokovian. Please send checks or money orders, in U.S. funds only, to: Michael Juliar, 355 Madison Ave., Highland Park, NJ 08904, USA.

*

[8]

For more on Field's folly, see the following important items: (1) Mrs. Véra Nabokov's reply to Field's ludricrous assertion that she "was a member of a team of assassins" in "Insight," Washington, DC Weekly, 22 December 1986; (2) Ross Wetzsteon's blistering review, "Stale Fire," Village Voice 30 December 1986, p. 5; (3) Dmitri Nabokov's reply to a sadly disinformed reviewer, "A Rejoinder, National Review, 30 January 1987, pp. 42-43; (4) Brian Boyd’s coup-de-grace review, Times Literary Supplement, 24 April 1987, pp. 432-33; (5) Dmitri Nabokov's review, "Did he really call his mum Lolita?," Observer, 26 April 1987; (6) Field's halting reply, Observer, 3 May 1987, p. 17.

*

— The first English translation of VN's "Pouchkine ou le vrai et le vraisemblable" (La Nouvelle revue française, Paris, 1 March 1937) will be published in December in The New York Review of Books. Dmitri Nabokov's inspired translation, "Pushkin, or the True and the Plausible," is preceded by his introduction which not only recounts the genesis of what was originally a speech, but also point the reader's attention to the uncannily apropos substance of VN's remarks on "fictionized biography." So long inaccessible to English readers, VN's thoughts on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Pushkin's death promise to be richly quoted in the future.

— On 20-22 February 1987 a Conference on Russian Literature and Psychoanalysis was held at the University of California-Davis. In an

[9]

afternoon session devoted to Nabokov, papers presented were: "The Psychosis of Charles Kinbote: A Key to Nabokov's Pale Fire," Peter Welsen (University of Regensburg): "Cloud, Castle, Claustrum: Nabokov as a Freudian in Spite of Himself," Alan Elms (University of California-Davis); "Splitting of the Ego: Freudian Doubles, Nabokovian Doubles," Geoffrey Green (San Francisco State University).

— For a book of articles on Nabokov's short stories, unpublished manuscripts are requested by Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809.

— There was a Nabokov session — "Close Readings of Nabokov's Prose" - at the AAASS National Convention held in Boston in November. The papers read were "Taking Nabokov Short Stories Literally," D. Barton Johnson; "The Spider and the Moth: In Cincinnatus's Cell," Gene Barabtarlo (University of Missouri); "De Consolatione Geographiae Universitatis: Nabokov's Pale Fire and the Works of King Alfred the Great," Priscilla Meyer.

— Don Johnson brings to our attention Carl Proffer's description of the dispute between Nadezhda Mandelshtam and Joseph Brodsky over the merits of VN's writings. It can be found in Carl R. Proffer, The Widows of Russia & Other Writings (Ann Arbor: Ardis) 1987, pp. 46-49.

*

Recent 1987 publications:

[10]

Harold Bloom, ed. Vladimir Nabokov. Modern Critical Views. New York: Chelsea House. Hardback. A collection of previously published articles selected and introduced by Harold Bloom.

___________. Vladimir Nabokov's LOLITA. Modern Critical Interpretations. New York: Chelsea House. Hardback. A collection of previously published articles on Lolita selected and introduced by Harold Bloom.

Stephen Jan Parker. Understanding Vladimir Nabokov. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, Understanding Contemporary American Literature series. Hardback and paperback.

*

Details concerning VN and Soviet television have been conveyed to us by Evgenii Borisovich Shikhovtsev. He writes that the first mention of Nabokov's name was in the context of a fall 1979 interview of Charles Johnston, the author of an English translation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin. In the beginning of 1980 Andrei Voznesensky, the well-known poet, read a verse about his mother which carried the line, "Liubit Bloka i Sirina" [she likes Blok and Sirin]. Then, in early 1987, Voznesensky referred to VN's views on the poetry of Khodasevich.

The first actual mention and citation of VN's writings on Soviet TV occurred on 24 May 1987 in the show, "The Writer and the Homeland." Professor V. I. Baranov, in the context of remarks on Russian émigré literature, read VN's 1927 poem, "Snimok," which had been

[11]

published in the October 1986 issue of "Knizhnoe obozrenie."

Mr. Shikhovtsev, a long-standing admirer and student of Nabokov's life and works, is one of the foremost specialists on Nabokov in the USSR. Over the years he has arduously compiled some remarkable materials, bibliographic and other, which we will be sharing with our readers in future issues.

*

NOTE — We have held the line for several years, but the inevitable increase in printing costs (up 40% since 1982) requires us to raise the yearly membership/subscription rate by $2.00 beginning with 1988 memberships/subscriptions. Please check the inside front cover of this issue for the new rates. We hope that you will maintain your membership and aid our efforts through timely renewal.

*

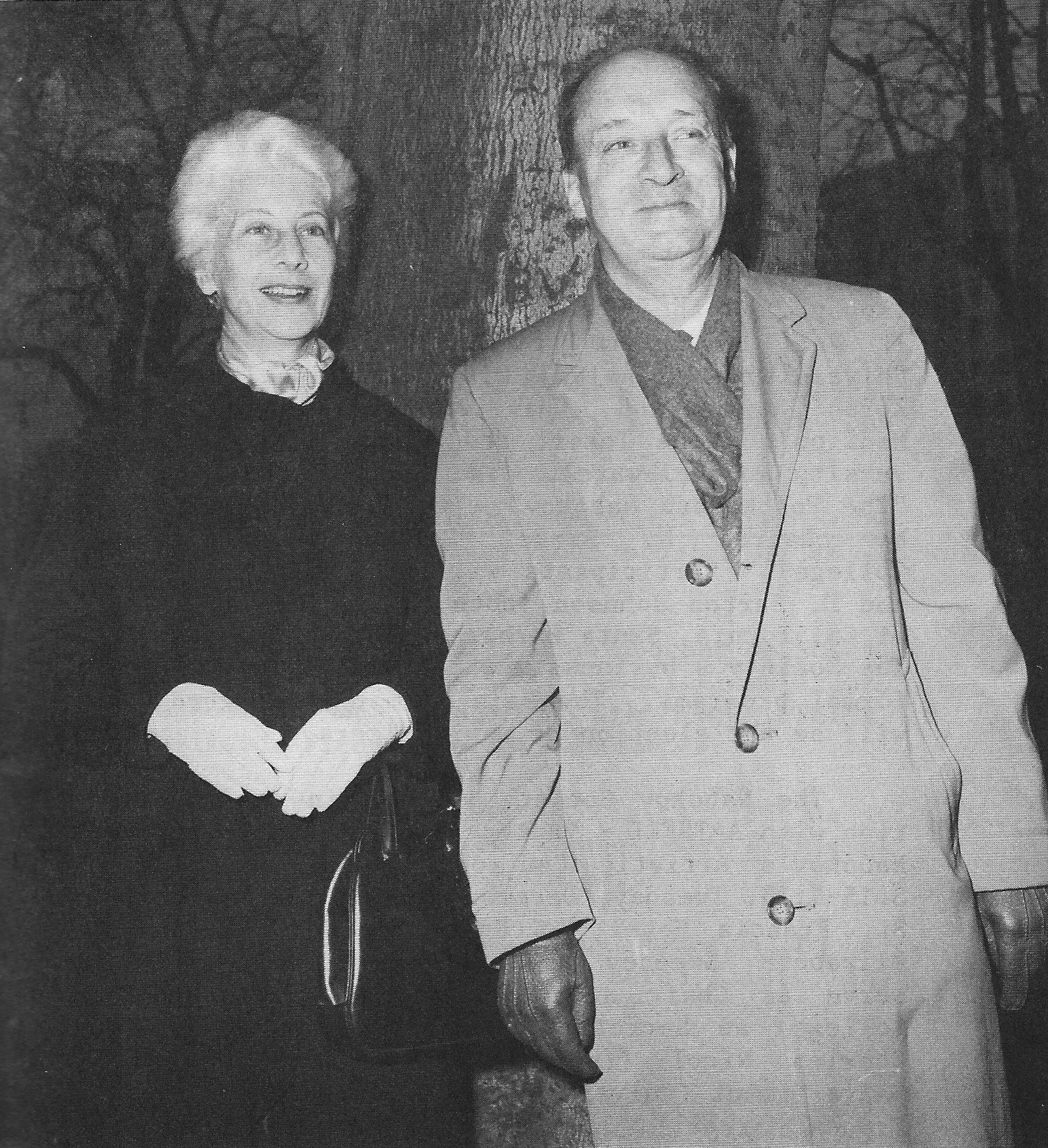

The photograph of Vladimir and Véra Nabokov was taken in Milan, 1959; photo credit to Ever Foto, Milano.

*

Once again, our thanks to Ms. Paula Malone for her invaluable aid in the preparation of this issue, and thanks also to Mr. Hyun Kim for his assistance.

*

[12]

Nabokov at the Bakhmeteff

by Zoran Kuzmanovich

Nabokov's nomadic life and his prolific production have made the study of archival materials connected with his works an international enterprise. Andrew Field's bibliography (McGraw-Hill, 1973), Michael Juliar's descriptive bibliography of Nabokov's writings (Garland, 1986), and The Nabokovian's supplements to Field and Juliar ease some of the complications of such study, but there is still Nabokoviana, especially correspondence, that has escaped cataloging. A recent publication of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies at the Wilson Center, Steven A. Grant and John H. Brown's The Russian Empire: A Guide to Manuscripts and Archival Materials in the United States (Boston: G.K. Hall, 1981), for example, lists three archives which house Nabokov's manuscripts, correspondence, and other materials which have not been fully examined by Nabokov's bibliographers. Research has turned up still other scattered items of Nabokoviana. The three repositories listed by Brown and Grant which yield items of interest are (1) the Library of Congress, (2) The Rare Books and Special Collections at Washington University Libraries in St. Louis, and (3) the Bakhmeteff Archive at the Butler Library of Columbia University in New York. The first two are confirmed by Juliar in his Appendix.

1. Some of the contents of the Nabokov Collection in the Library of Congress have already been made known to the readers of the

[13]

VNRN #3 (1979). Brown and Grant list three other Library of Congress collections that contain additional Nabokoviana. The first of these is the restricted Bollingen Foundation Collection. It contains correspondence pertinent to Nabokov's translation of Eugene Onegin. The second is the Vozdushnie Puti (Aerial Ways) Collection which contains, among his contributions to that journal and his correspondence with its editor Roman Grynberg, some photographs of Nabokov. The last Library of Congress collection listed by Grant and Brown as having some Nabokov materials is the Rachmaninoff one. However, in one of those inexplicable Nabokovian events, those letters have disappeared since cataloging.

2. The Washington University Libraries Rare Books and Special Collections Archive houses ten items covering the period from 1958 to 1964. These items include three letters (March 12, 1958-June 7, 1959) from Mrs. Vera Nabokov to Peter Russell, the translator of Mandelshtam. The letters concern Nabokov's books, translations, and his opinions about others' translations and views of translation. Nabokov's revisions of the quotations he prepared for the Jane Howard interview make most interesting reading if read side by side with the final version of the interview published in Life magazine, November 20, 1964, under the title "The Master of Versatility — Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita, Languages, Lepidoptera" and reprinted in Strong Opinions, 46-50. Also at Washington University Libraries, but in the Howard Nemerov rather than the Nabokov Papers, is a letter (February 18, 1957) from Nabokov commenting upon Nemerov's novel The Homecoming Game.

[14]

3. The one place that offers greatest rewards to the Nabokov scholar is the Bakhmeteff Archive of Columbia University's Butler Library. Boris Alexandrovich Bakhmeteff (1880-1951), the Russian Ambassador to the United States during the brief reign of Kerensky' s Provisional Government, stayed in the United States after the Revolution(s), resigning his post only in 1922 when it became clear that he was without a country to represent. He became a professor of civil engineering at Columbia University, and his papers, along with 900 other collections, largely donations and purchases of émigré papers, form the Bakhmeteff Archive.

There are eleven collections in the Bakhmeteff Archive containing Nabokov's manuscripts and correspondence. (There is also the Nabokov Family Collection; its treasures include letters to Nabokov’s ancestors from Count Witte and Tsars Alexander II and Nicholas II.) The Dobuzhinsky collection is restricted as is the Trilling one (housed at Butler Library, but not a part of the Bakhmeteff Archive) and scholars must secure permission from relatives and trustees. (The Aldanov, Grynberg, and Zenzinov collections also contain correspondence from Edmund Wilson which pertains to Nabokov but is not cataloged as such). The unrestricted collections are presented here alphabetically by the title of the collection, with brief annotations of the most interesting items. The transliteration system duplicates the one used by the Bakhmeteff archivists.

Collection Aldanov. [Mark Aleksandrovich (1889-1957), writer and editor of The New

[15]

Review whose unavailability to lecture at Stanford in 1940 provided Nabokov with the opportunity to come to the United States].

There are twenty eight letters and four post cards to Aldanov covering the years 1946-1956. In some cases, the letters are accompanied by carbon copies of Aldanov's replies. These items can be divided into those which deal primarily with the European period of emigration and those which cover the American one. The more interesting letters among the latter indicate that Nabokov corrected the English versions of Aldanov's stories and provided him with details about English literature, such as who the person from Porlock was. (Nabokov had thought of titling Bend Sinister after the cognomen of the spectral figure Coleridge had introduced.) Other letters contain hints about a possible continuation of The Gift; Nabokov's outrage over the publication (in Aldanov’s The New Review, 1-3) of Alexandra Tolstoy's The Predawn Haze which Nabokov took to be anti-semitic in tone; negotiations for publishing Nabokov's work in The New Review and Nabokov's evaluations of various early issues of that journal (with praise for Aldanov's work on Merezhkovsky, Herzen, and Hugo). Included among these letters in a discussion of the tenderness with which Nabokov suffused Lolita and Nabokov's explanation of Lolita's origin in the 1939 novella Volshebnik, published since as The Enchanter (Putnam, 1986).

Letters covering the pre-war years in Europe contain discussions of Nabokov's attitude toward Bunin, Nabokov's refusal to attend

[16]

the meeting of Russian writers (he was unwilling to associate with Narokov, Bushuev, Adamovich, Ivanov, and Burov), adverse criticism of the work of Berdyaev and Sorokin and of Vishniak's piece on Khodasevich.

Collection Chekhov Publishing House

In this collection are letters, postcards, and telegrams sent by Nabokov from 1951 to 1955 to Nicholas Wreden, Tatiana Georgievna Terenteva, and Vera Aleksandrova, functionaries of the Chekhov Publishing House. Most of these materials pertain to business matters relative to Nabokov’s preface to a collection of Gogol's St. Petersburg tales, the publication of The Gift, possible translation by Nabokov of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea into Russian, and Nabokov's offers of The Defense and Despair for publication.

By far the most interesting item here is an unsigned page of comments on The Gift by someone who appears to have functioned as a publisher’s reader or a blurb writer. The page is included with Nabokov's letter of March 31, 1952. Three clues may help with determining the identity of this reader. The writer's incomplete control of English, the use of slashes instead of parentheses for enclosing explanatory material within the sentence, the slightly off-center small case "c" and capital "o" of the pica typescript point to Aldanov as the most likely candidate. The other possibility is that Aldanov and the writer of the blurb had access to the same typewriter. Vera Aleksandrova's letter to Nabokov, dated September 6, 1951, mentions Aldanov’s contribution to the publication of

[17]

The Gift, but does not specify what that contribution was.

Collection Goldenweiser, [Alexis or Aleksei Aleksandrovich, a lawyer associated with the Union of Russian Jews].

This collection offers two items of interest to students of reader response theories. One is Goldenweiser's spontaneous and enthusiastic reaction in 1937 to an installment of The Gift in Contemporary Annals. Tongue in cheek, he recounts his own experiences with the law firm of Traum, Baum, and Kasebier. A similar enthusiastic reaction and a catalog of the highlights of Nabokov's Gogol comprise the other letter.

Collection Grynberg, [Roman Nikolaevich (1896-1967), editor of Experiments and Aerial Ways].

Letters and postcards in this collection cover the period between 1943 and 1963 and refer to Ivan Bunin, Khodasevich, Sorokin, Vishniak, Aldanov, Gogol, Edmund Wilson, Joyce, Doctor Zhivago (Nabokov hoped the Grynbergs had been cured of him), the possibility of translating Lolita into Russian for Grynberg's Aerial Ways, criticism of Cournos's anthology of Russian poetry and of Somerset Maugham. One of the letters discusses those portions of Conclusive Evidence which offer Nabokov's opinions Of his fellow émigré writers . Edmund Wilson did not approve of the chapter containing these opinions, but Nabokov thought them very strong (in the French sense of "strong"), adding that they were philosophically and structurally justifiable.

[18]

In the manuscript portion of this collection there is a poem, in Russian, which carries the dedication "To Roman and Sonia from the hero of The Gift" and is signed" (For F. Godunov-Cherdyntsev) V. Nabokov-Sirin, 9.XII. 1951." The poem is included as a part of The Gift on page 107 of the Russian original , 106 of the English translation.

Collection Kagan, [Abram Saulovich (with the Petropolis publishing house in Berlin) ].

The collection contains five post cards sent to Kagan from various places in October, November, and December of 1938. Nabokov was trying to arrange terms for the publication of the complete version of The Gift. He indicated that the book was his favorite and shrewdly suggested that the previously unpublished Chapter Four would increase the interest of the readers. Other cards negotiate author's percentages and the book's size, that is, whether the book ought to be in two volumes.

Collection Potresov, [Sergei Viktorovich, (1870-1953); he sometimes wrote under the name S.V. Yablonovsky].

One of the Nabokov items in the collection is a handwritten three page letter of 28 September, 1921, in which Nabokov thanks Potresov for his praise of Nabokov's work and jokes about his muse being twelve years old. Nabokov also tells of translating (at ten years of age) Mayne Reid’s Headless Horseman: Strange Tale of Texas into French alexan-

[19]

drines, of kisses and crocodiles, of the gay flavoring in the stories with which he filled his school notebooks, of his activities from 1915 to 1921, and of his fear that his writing was in vain until he received Potresov's letter of appreciation. Though it may seem as if Nabokov's expression of gratitude to someone for that person's positive reaction to his work contradicts his favorite fact about himself (that he has never thanked a reviewer for a favorable review), the simple fact is that Potresov was not a reviewer.

In the manuscript portion of the Potresov collection, on page 47 of Potresov's autograph album, dated Paris, February 1939, there is an untitled poem "Na zakate, u toi-zhe skam'i" ("At sunset, by the same bench"). In the dedication to Potresov, Nabokov hints that these verses were inspired by Aleksander Blok. For more information on this poem, see the three entries under its title in the index of Juliar's bibliography.

Collection Sablin, [Evgenii Vasilevich, the last Russian diplomat in the Imperial Embassy in London].

Three letters, two undated, one dated 31 January 1937, primarily concerned with seeking a position.

Collection Vernadsky, [Georgy Vladimirovich (1887-1973), historian of the Masonic movement in Russia].

Here may be found a letter from Nabokov of 12 September 1936 to Mikhail Ivanovich Rostovtsev (1870-1952), a historian of Greek

[20]

and Roman times, associated with the Russian Liberation Committee in London. Citing his desperate economic circumstances, Nabokov recommends himself as a lecturer in English and French, even on such distasteful subjects as the Russian Marxists of 1860s, a topic Nabokov was in command of because of his research for The Gift.

Also in the Vernadsky collection, but addressed to Vernadsky himself (who was teaching at Yale by this time), are five letters and three post cards (1937-1942), most of which ask for help with finding a position for Nabokov as a lecturer in Russian at Harvard or Yale.

Collection Yarmolinsky, [Avram Savelievich (1890- )].

There are four letters from Nabokov (1940-1952), the most interesting of which deals with the near impossibility of translating The Gift, Nabokov's faithfulness to his sources in the Chernyshevsky chapter, and the quality of the Eugene Onegin translations, including that of Yarmolinsky's wife, Babette Deutsch. Portions of this collection are restricted.

Collection Zeeler, [Vladimir Feofilovich (1874-1954), a journalist, secretary of the Union of Soviet Writers and Journalists in Paris, and editor of Russian Thought].

This letter from 193? contains a rare thank you from Nabokov for Zeeler's appreciation of Nabokov's books. Again, like Potresov, Zeeler was not a professional reviewer.

[21]

Collection Zenzinov, [Vladimir Mikhailovich (1880-1953), the first editor of The Will of Russia, contributor to Contemporary Annals, and memoirist. He should really be known for his account of the deserted children in the early years of Soviet Union.]

This collection offers some vintage playfully serious Nabokov.

Item 1. Nabokov excuses his not calling on Zenzinov by hinting that he got Newark and New York confused.

Item 2. Nabokov apparently forgets whether he sent a letter to Zenzinov inquiring if Zenzinov had rescued the Nabokov papers from Europe and sends another, very similar one, dated the same day.

Item 3. Nabokov refuses to sign a petition that Zenzinov had circulated with the comment that he does not sign things he had not written himself.

Item 4. Nabokov classifies all émigrés into five major groups: 1. Those who hate the Bolsheviks for confiscating their goods; 2. Victims of pogroms; 3. Idiots; 4. Philistines and social climbers; 5. Members of old intelligentsia intolerant of tyranny.

Included in the Zenzinov collection is a five page essay Nabokov wrote in memory of Amalia Osipovna Fondaminsky, the wife of Ilya Isidorovich Fondaminsky, one of the editors of Contemporary Annals. The essay formed pages

[22]

69-72 of a book privately published on the occasion of Mrs. Fondaminsky's death. The typescript essay is a variant, and includes two paragraphs which were not printed in the 1937 book published in Paris.

Also in the Zenzinov collection are manuscripts (12 pages) of materials from which Nabokov read during his appearances in 1949.

I am indebted to David Kraus of the Library of Congress' European Division, Timothy D. Murray of Washington University Libraries , Alex Rollich of the University of Wisconsin's Memorial Library, Nick Paley of Beloit College's Department of Modem Languages , Ellen Scaruffi, Kenneth Lohf, Hugh Wilburn, and Rudolph Ellenbogen of Columbia University's Butler Library for their generous assistance in tracking down and making available the items listed above.

[23]

Émigré Responses to Nabokov (III): 1936-1939

by Brian Boyd

Note: as in previous installments, an asterisk after an entry denotes information recorded from clippings in the Nabokov archives that it has not yet proved possible to verify independently from an intact original.

R. F. "O Sirine" ("On Sirin").

[VN: general comments in preparation for public reading in Brussels.]

Russkii Ezhenedel'nik v Belgii (?) c. 21 Jan. 1936.*

Georgii Adamovich. "Vecher V. Sirina i V. Khodasevicha" ("Sirin-Khodasevich Reading").

[VN: public reading with Khodasevich, Paris, 8 February.]

Poslednie Novosti, 13 Feb. 1936 (#5439), p. 3.

M. [Iurii Mandelshtam]. "Vecher V.V. Sirina i V.F. Khodasevicha" ("Sirin-Khodasevich Reading") .

Vozrozhdenie, 13 Feb. 1936.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Nov* 8.

[VN: poem "Tolstoy."]

Poslednie Novosti, 20 Feb. 1936 (#5446), p. 3.

[24]

M. [Iurii Mandelshtam]. Review of journal Nov’ 8.

[VN: poem "Tolstoy."]

Vozrozhdenie, 20 Feb. 1936 (#3914), p. 4.

Gaito Gazdanov. ") molodoi emigrantskoi literature" ("On young emigré literature").

[VN: Sirin as exception to the failed promise of young émigré literature.]

Sovremennye Zapiski, 60 [28 Feb.] 1936, pp. 404-08.

Georgii Adamovich. "Perechityvaia 'Otchaianie'" ("Rereading ’Despair'").

[VN: survey article on publication of Otchaianie in book form.]

Poslednie Novosti, 5 March 1936 (#5460), p. 3.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 60.

[VN: Priglashenie na kazn‘, Chs. 14-20.]

Poslednie Novosti, 12 March 1936 (#5467), p. 2.

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 60.

[VN: Priglashenie na kazn‘, Chs. 14-29.]

Vozrozhdenie, 12 March 1936 (#3935), p. 3-4.

[25]

Vladimir Kadashev. "Dushnii Mir" ("A Suffocating World").

[VN: survey article.]

Novoe Slovo, 27 March 1936, p. 2.

Gleb Struve. "O V. Sirine" ("On Sirin").

[VN: survey article in preparation for public reading in London.]

Russkii v Anglii, 15 May 1936 (#9), p. 3.

Georgii Adamovich. "Po povodu 'Peshchera'"

[VN: compared with Aldanov.]

Poslednie Novosti, 28 May 1936 (#5544), p. 2.

Vladimir Weidle. Review of OTCHAIANIE.

Krug, 1 [early July] 1936, pp. 185-87.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Krug 1.

[VN: influence on Yanovsky.]

Poslednie Novosti, 9 July 1936 (#5585), p. 3.

Petr Bitsilli. "Vozvrozhdenie allegorii"

[VN: compared with Saltykov-Shchedrin.]

[26]

Sovremennye Zapiski, 61 [mid-July] 1936, pp. 191-204. Trans. D. Barton Johnson, in Carl Proffer, ed. A Book of Things About Vladimir Nabokov (Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1974), pp. 63-69; rpt. Norman Page, ed., Nabokov: The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982), pp. 56-60.

Vladimir Varshavsky. "O proze 'Mladshikh' Emigrantskikh Pisateley" ("On the prose of the 'young’ émigré writers")

[VN: reply to Gazdanov; VN and the theme of solitude.]

Sovremennye Zapiski, 61 [mid-July] 1936, pp. 409-14.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of Sovremennye Zapiski 61.

[VN: story "Vesna v Fial’te" ("Spring in Fialta").]

Poslednie Novosti, 30 July 1936 (#5606), p. 3.

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of Sovremennye Zapiski 61.

[VN: "Vesna v Fial'te."]

Vozrozhdenie, 8 Aug. 1936 (#4038), p. 7.

Petr Bitsilli. "Neskol'ko zamechanii o sovremennoy zarubezhnoi literature" ("A Few Notes on Contemporary Emigré Literature").

[27]

[VN: compared to Gogol; will be part of Russian literature as long as it lasts.]

Novii Grad, 11 (1936), pp. 131-35.

N. Volkovyskii. "Nemetskii kritik o russkikh zarubezhnikh pisateliakh" ("German Critic on Russian Emigré Writers").

[VN: summarizes Arthur Luther on Mashen’ka.]

Russkoe Slovo, 196 (1936-37?).

Mark Aldanov. "Vechera 'Sovremennykh Zapisok'"

[VN: review of his reading from Dar, Paris, 24 January: "an uninterrupted torrent of the most unexpected formal, stylistic, psychological and artistic finds."]

Poslednie Novosti, 28 Jan. 1937 (#5788), p. 3.

M. [Iurii Mandelstam]. "Vecher V.V. Sirina"

[VN: public reading.]

Vozrozhdenie, 30 Jan. 1937 (#4063), p. 9.

Vladislav Khodasevich. "O Sirine"

[VN: introductory talk from public reading. ]

[28]

Vozrozhdenie, 13 Feb. 1937 (#4065), p. 9. Trans, in part, Simon Karlinsky and Robert Hughes, in Page, Nabokov: The Critical Heritage, pp. 61-64.

Gleb Struve. "Vladimir Sirin-Nabokov — k ego vecheru v Londone 20-go fevralia" ("Vladimir Sirin—for his London reading, February 20").

[VN: survey, and current controversies.]

Russkii v Anglii, 16 Feb. 1937 (#3/27), p. 5.

"Literaturnii vecher V. Sirina" ("Sirin Literary Evening")

[VN: review of public reading, London, 20 February.]

Russkii v Anglii, 3 March 1937 (#4/28), p. 2.

Petr Pilskii. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 63.

[VN: Dar (The Gift), Chapter l.]

Segodnia, 29 April 1937 (#117), p. 3.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 63.

[VN: Dar, Ch. 1.]

[29]

Poslednie Novosti, 6 May 1937.

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 63.

[VN: Dar, Ch. 1.]

Vozrozhdenie, 15 May 1937 (#4078), p. 9.

Zinaida Shakhovskoi. "Un Maitre de la jeune litterature russe: Wladimir Nabokoff-Sirine."

[VN: survey article.]

La Cite Chrétienne, Brussels, 20 July 1937.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 64.

[VN: part of Dar, Ch. 2; comparison with Gaidanov.]

Poslednie Novosti, 7 Oct. 1937 (#6039), p. 3.

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 64.

[VN: part of Dar, Ch. 2.]

Vozrozhdenie, 15 Oct. 1937 (#4101), p. 9.

___________. Review of journal Russkie Zapiski 2.

[30]

[VN: story "Ozero, oblako, bashnia" ("Cloud, Castle, Lake."]

Vozrozhdenie, 26 Nov. 1937 (#4107), p. 9.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Russkie Zapiski 2.

[VN: part of Dar, Ch. 2.]

Poslednie Novosti, 16 Dec. 1937 (#6109), p. 3.

___________. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 65.

[VN: Dar, part of Ch. 2.]

Poslednie Novosti, 20 Jan. 1938, p. 3.

Mikhail Osorgin. "Literaturnie razmyshleniia" ("Literary Reflections").

[VN: on Dar, Ch. 2.]

Poslednie Novosti, 14 Feb. 1938 (#6169), p. 2.

V.S. Mirnii. Review of journal Russkie Zapiski 1 and 2.

[VN: mention of "Ozero, oblako, bashnia."]

Illiustrirovannaia Rossiia, 19 Feb. 1938 (39), p. 16.

[31]

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 65.

[VN: Dar, end of Ch. 2, beginning of Ch.3.]

Vozrozhdenie, 25 Feb. 1938 (#4120), p. 9.

'"Sobytie'—p'esa V. Sirina" ("Sirin's Play 'The Event’").

Poslednie Novosti, 2 Feb. 1938 (#6182), p. 2.

K. P. [K.K. Parchevsky]. "Russki Teatr. 'Sobytie' V. Sirina" ("The Russian Theater. V. Sirin's 'The Event'").

[VN: review of premiere of Sobytie]

Poslednie Novosti, 6 March 1938 (#6189), p. 5.

"V Russkom teatre" ("In the Russian Theater").

[VN: review of second performance of Sobytie.]

Poslednie Novosti, 9 March 1938 (#6192), p. 3.

Sizif. "Otkliki" ("Reactions").

[VN: on difference between audience reaction on premiere and second night of Sobytie.]

Poslednie Novosti, 10 March 1938 (#6193), p. 3.

[32]

Zritel' iz XIV arrondismana (Theatergoer from the XIV arrondissement). "'Sobytie,' p’esa V. Sirina (pis'mo v redaktsiyu)" ("Sirin's Play 'The Event': letter to the editor").

[VN: on second night of Sobytie. With reply from editors.]

Poslednie Novosti, 10 March 1938 (#6193), p. 4.

I.S. "Russkii Teatr. Sobytie,' P'esa Sirina" ("Sirin's Play 'The Event'").

Vozrozhdenie, 11 March 1938, p. 12.

Lollii Lvov. Review of SOBYTIE.

Illiustrirovannaia Rossiia, 12 March 1938 (#12), p. 14.

N.P.V. [N.P. Vakar]. "'Sobytie'—p'esa V. Sirina (Beseda s Yu. P. Annenkovym)" ("Sirin's Play 'The Event': Conversation with Yu. P. Annenkov").

[Interview with director of Sobytie.]

Poslednie Novosti, 12 March 1938 (#6195), p. 4.

"Russkiy teatr" ("The Russian Theater").

[VN: third performance of Sobytie.]

Poslednie Novosti, 15 March 1938 (#6198), p. 4.

[33]

Lolii Lvov. "Eshchyo o 'Sobytie’” ("More About 'The Event'").

Illiustrirovannaia Rossiia. 19 March 1938 (#13), p. 17.

Iurii Sazonov. "V Russkom teatre" ("In the Russian Theater").

[Review of SOBYTIE.)

Poslednie Novosti, 19 March 1938 (#6202), p. 4.

Andrey Garf. "Literaturnie pelenki" ("Literary Swaddling").

[VN: Nazi denunciation.]

Novoe Slovo, 20 March 1938, p. 7.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of Leonid Zurov, Pole (The Field).

[VN: mention: stands quite apart from other young émigrés.]

Poslednie Novosti, 24 March1938 (#6207), p. 3.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Russkie Zapiski 4.

[VN: Sobytie.]

Poslednie Novosti. 21 April 1938 (#6235), p. 3.

[34]

Vladislav Khodasevich. "'Sobytie' Sirina v Russkom teatre" ("Sirin's 'The Event’ in the Russian Theater").

Sovremennve Zapiski, 66 [17 May] 1938, pp. 423-27.

K. P——ov. "Russkii teatr. Itogi sezona" ("The Russian Theater: Summing up the season") .

[VN: Sobytie.]

Poslednie Novosti, 20 May 1938 (#6263), p. 5.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 66.

[VN: Dar, Ch. 3, conclusion.]

Poslednie Novosti, 2 June 1938 (#6276), p.

Georgii Adamovich. "Literaturnye Zametki" ("Literary Notes").

[VN: mention of translations of Pushkin.]

Poslednie Novosti, 9 June 1938 (#6283), p. 3.

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 66.

[VN: Dar, Ch. 3, conclusion.]

Vozrozhdenie, 24 June 1938 (#4137), p. 9.

[35]

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of Russkie Zapiski, April-July.

[VN: Sobytie.]

Vozrozhdenie, 22 July 1938 (#4141), p. 9.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Russkie Zapiski, September.

[VN: story "Istreblenie tiranov" ("Tyrants destroyed").]

Poslednie Novosti, 15 Sept. 1938.

S. Savelev [Savely Sherman]. Review of SOGLIADATAI.

Russkie Zapiski, 10 (October 1938), pp. 195-97.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 67.

[VN: Dar, Ch. 5.]

Poslednie Novosti, 10 Nov. 1938.

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 67.

[VN: Dar, Ch. 5.]

Vozrozhdenie, 11 Nov. 1938 (#4157), p. 9.

Lidiia Chervinskaia. "Po povodu ‘Sobytiia' V. Sirina" ("On Sirin's 'The Event'").

[36]

Krug, 3 [mid-Nov.] 1938), pp. 168-70.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Russkie Zapiski, November.

[VN: play Izobretenie Val'sa (The Waltz Invention).]

Poslednie Novosti. 23 Nov. 1938.

Zinaida Shakhovskoi. "Un nouveau livre de Wladimir Sirin-Nabokoff."

[Review of PRIGLASHENIE NA KAZN'.]

La Cite Chrétienne (?), c. Dec. 1938/ Jan. 1939.*

Sergei Osokin. Review of PRIGLASHENIE NA KAZN'.

Russkie Zapiski, 13 ([7] Jan. 1939, pp. 198-99.

Vladimir Weidle. ”20 let Evropeyskoy literature” ("Twenty Years of European Literature").

[VN: innovator like Döblin, Broch, Kafka; describer of contemporary Life, like Broch, Dos Passos.]

Poslednie Novosti, 10 Feb. 1939 (#6528), p. 3.

Petr Pilskii. Review of journal Russkie Zapiski 14.

[37]

[VN: story "Lik" ("Lik").]

Segodnia, 15 Feb 1939 (#46), p. 4.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Russkie Zapiski 14.

[VN: "Lik."]

Poslednie Novosti, 16 Feb. 1939 (#6534), p. 3.

Petr Bitsilli. Review of PRIGLASHENIE NA KAZN’ and SOGLIADATAI.

Sovremennye Zapiski, 68 ([10 March] 1939), pp. 474-77.

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 68.

[VN: story "Poseshchenie Muzeia" ("The Visit to the Museum").]

Vozrozhdenie, 24 March 1939 (#4176), p. 9.

Petr Pilskii. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 68.

[VN: "Poseschenie Muzeia."]

Segodnia, 24 March 1939 (#83), p. 2.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 68.

[38]

[VN: "Poseshchenie Muzeia."]

Poslednie Novosti, 20 April 1939.

M.K. "Iavlenie Val’sa."

[VN: meditation using Izobretenie Val'sa as starting point.

Sovremennye Zapiski 69, ([24 July] 1939), pp. 355-63.

Iurii Mandelstam. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 69.

[VN: ?]

Vozrozhdenie, 4 Aug. 1939 (#4195), p. 9.

Georgii Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 69.

[VN: poem "Poety" by "Vasiliy Shishkov" and tribute to Khodasevich.]

Poslednie Novosti, 17 August 1939 (#6716), p. 3.

Georgii Adamovich. "Literaturnye Zametki" ("Literary Notes").

[Is VN Shishkov?]

Poslednie Novosti, 22 Sept. 1939 (#6572), p. 3.

[39]

Nabokov in the USSR (Continued)

by Stephen Jan Parker

In the words of one Soviet commentator, Nabokovmania is sweeping the USSR. Here is an overview of events thus far in 1987.

In the newspaper, Moskovskie Novosti, 22 February, p. 10 appears "Iskus 'Zapretnogo' ploda. K vykhodu proizvedenii Vladimira Nabokova." [The Temptation of forbidden fruit. On the appearance of the works of Vladimir Nabokov], signed Vladimir Leksin. The most important question, says Leksin, is to determine what the proper attitude toward Nabokov should be. He places VN in the company of other once forbidden authors —Akhmatova, Tsvetaeva, Platonov, Bulgakov, Kafka, Hemingway in For Whom the Bell Tolls, Pasternak, Mandelshtam, Gumilev, Khodasevich, Zamiatin.

— In the newspaper, Sovetskaia Rossiia, 20 February, p. 4 appears "Vyvod sdelaite sami" [Draw your own conclusions], by Lev Liubimov, and "Vmesto zakliucheniia" [In place of a conclusion] by G. Orekhanov. In the former it is noted that the editor has been receiving many letters concerning the appearance of works by VN, Gumilev, Khodasevich. The recurring question is how they should be received by readers. In the latter piece Orekhanov quotes from Liubimov’s book on the Russian emigration, in which the old émigré view of VN as a cold stylist outside of the Russian literary tradition is repeated. This is then followed by a defense of the values of traditional Soviet Russian literature.

[40]

— In the newspaper, Severnaia pravda, 10 February, p. 3, on a page devoted to the Pushkin celebrations appears "Perevod s russ-kogo" [A translation from the Russian] in which E. B. Shikhovtsev explains and lauds VN's translation and commentary to Pushkin's Eugene Onegin. Shikhovtsev points out that VN's work is of value even to USSR Pushkinists.

— The magazine Ogonyok no. 15, 1987 carries an interview with Bela Akhmadulina, a well known Soviet poet. In the interview she describes her meeting with VN in Montreux in March 1977, several months before his death. She calls it one of the most important events in her life.

— The newspaper, Moskovskii literator, November 14, carries a speech by Feliks Kuznetsov First Secretary of the Moscow Union of Writers. Entitled "Perestroika — Delo kazhdogo" [Restructuring — Everyone's affair] it carries references to "the new modishness of Gumilev and Nabokov" on page 4. Kuznetsov remarks that though he was in favor of publication of The Defense, he is upset when he sees that VN's poems published in Khizhnoe obozrenie (October 14, 1986) carry claims that VN belongs in the line of classic Russian writers. Kuznetsov stresses that VN was a foe of the Russian revolution, and strongly reminds his listeners that "perestroika" does not mean abandoning the Revolution and its socialist principles.

In Literatumaia gazeta of March 18, p. 5, B. Baranov comments in "Vo s to rzhenno ili obiektivno? O nekotorykh literaturnykh publi-

[41]

katsiiakh poslednego vremeni" [Rapturously or objectively? About several recent literary publications] that though The Defense certainly is written in a marvelous style, it is about a defense against life. He attacks Voznesensky's positive view of VN.

— Novyi mir no. 4, April 1987, pp. 173-227 publishes VN's Nikolai Gogol, with an introduction by Sergei Zalygin (chief editor). The translation was rendered by the late Elena Golysheva in 1980 or 1981. It was offered to various journals and rejected. In 1986 Larisa Bespalova contacted Golysheva's son and asked for the MS for Novyi mir. The contribution of Viktor Golyshev, her son, was to search out quotations which VN uses in his book but without direct citations. Bespalova then collated the translation MS with VN's original. See Gene Barabtarlo's note on this translation in the Annotations section of this issue.

— Inostrannaia literatura, no. 5 (May) carries VN's translations, "Dekabr'skaia noch"' (from Musset) and "P'ianyi korabl'" (from Rimbaud) and an article by N. Anastas'ev.

— Literaturnaia gazeta of May 20, p. 5, publishes A. Muliarchik’s "Fenomen Nabokova" [The Nabokov phenomenon] in which Muliarchik takes issue with those who claim to find nothing enchanting in VN's work. He points out that broad conclusions are being drawn based largely on only one novel, The Defense. He reminds his readers that VN was the author of eight [sic] novels and many stories, plays, and poems in Russian. He then speaks about the dual language phenomenon in VN. He refers

[42]

to VN's view of Soviet poshlost in The Defense, and refers to VN's views on "art for art's sake." He pointedly notes that some commentators link VN with Chekhov, another writer who was opposed to social commentary in imaginative literature.

— In the newspaper, Moskovkie novosti no. 21, May 24, appears the short piece, "Vam zaplatiat, Ms'e Nabokov!" [You will be paid. Monsieur Nabokov] by Melor Sturud. Sturud replies to Dmitri Nabokov's interview with Voice of America. Sturud misunderstands Dmitri's concern with the way in which VN's works are being selected, translated and presented in the USSR without any prior contact with the Nabokov family. Sturud prefers to understand it as a demand for the payment of royalty rights. [As if anyone would want Russian rubles!]

— The newspaper, Moskovskii literator May 15, p. 3, publishes "O Vladimire Nabokove" [About Vladimir Nabokov] by V. Afanas'ev. He reports the various views of VN published in the press and the central question of VN's relation to Russian culture. He feels that one can orient one’s views differently according to which VN work one refers to. He speaks about Shikhovtsev’s work, and informs readers of the existence of The Nabokovian and The Vladimir Nabokov Society!!

— In Literaturnaia gazeta June 3, 1987 the unsigned piece, "Chitatel1-gazeta-chitatel"’ [Reader-Newspaper-Reader] reports that two weeks earlier readers of Literaturnaia gazeta were asked to name the best items in the May 20 edition. Responses reveal that the most

[43]

popular was Muliarchik's article, "The Nabokov phenomenon."

— Druzhba narodov, no. 6 (June) publishes eight VN poems, including the full text of "Slava" (Fame, 1942).

— Iunost' , no. 6 (June) publishes VN's "Le Vrai et le vraisemblable" translated from the French under the title, "Pushkin, ili pravda i pravdopodobie," on pages 90-93, with a photo of VN. In an accompanying piece, "From the Translator," Tatiana Zemtsova presents a brief sketch of VN’s life and works.

— [The New York Times Magazine of July 18 publishes an exchange of letters between Vladimir Voinovich (exiled Soviet writer) and Sergei Zalygin (chief editor of Novyi mir) between March 24 and May 17, 1987. Voinovich, once a favorite author of Novyi mir before being exiled in 1980, writes to Zalygin following Zalygin's speech at the University of Paris. In that speech Zalygin had spoken about glasnost' and his plans to publish suppressed authors in Novyi mir. Voinovich offers his own works: Zalygin demurs. Voinovich charges that Zalygin is only interested in publishing dead authors. Zalygin replies there are limits to glasnost', and speaks of publishing Platonov, Nabokov, Bulgakov, Pasternak. ]

— Ogonyok no. 28 (July) pp. 10-11 publishes VN's story "Krug" ["The Circle"]. In an afterword, V. Enisherlov says that he is proud to introduce VN the short story writer. He notes the great interest in VN's writings, and says that the publication of VN's works is a very good thing.

[44]

— Literaturnaia gazeta, September 2, publishes "Literaturnaia panorama", unsigned, in which the editor of Druzhba narodov reports that next year VN's Drugie berega [the Russian edition of VN's memoirs] will be published.

— The newspaper, Molodoi Leninets, September 3, publishes four VN poems along with a short essay by Evgenii Shikhovtsev.

— Ogonyok, no. 37 (September) p. 8, carries a photo of VN, and an extract from the anthology of poetry, Russkaia Myza XX Veka [Russian Muse of the Twentieth Century], selections and introduction by Evgenii Evtushenko. The extract consists of five poems by VN and brief laudatory remarks by Evtushenko.

*

Reports and rumors concerning past and future VN matters in the USSR:

1. It is reported that at a concert given last year in Moscow's Manezh, Alexander Grad-sky sang some of his own ballads composed on VN's verse.

2. Mashen'ka [Mary] will be published in Literaturnaia ucheba no. 6, Nov-Dec 1987, along with a round-table discussion by VI. Gusev and P. Palamarchuk.

3. Efforts are being made to have "University Poem" and "Anya v strane chudes" [VN's translation of Alice in Wonderland] published.

4. Several VN stories are under consideration by the journal Znamia.

[45]

5. It is rumored that the journal Druzhba narodov will publish Priglashenie na kazn’ [Invitation to a Beheading] in 1988.

6. There is a rumor that the rare monthly, Rodnik (Riga, published in Russian and Lettish) already started, last August, to serialize Priglashenie na Kazn’.

7. It is rumored that publishing houses in Moscow are considering (1) a single volume of VN works which will include Zashchita Luzhina [The Defense] and several stories and/or (2) a volume of VN works which will include Dar [The Gift], Priglashenie na kazn', and some poetry.

8. It is rumored that there is interest in publishing some of VN's literary criticism, such as his Cervantes lectures.

More in the next issue.

[46]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

[Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov's works will be to the most recent hardcover U.S. editions.]

The Twin Abysses of "Lik"

As Andrew Field has pointed out (Life in Art, 194), the plot of "the 1938 story "Lik" appears to be a play on the idiom "I'd like to be in your shoes." A Russian émigré actor bearing the stage-name Lik is touring France with a provincial theater company when he meets by chance an acquaintance from his childhood — one Koldunov, formerly the tormentor of Lik’s schooldays but now an embittered and derelict drunkard. Lik finds himself invited to the latter’s home, where he is preyed on for a hand-out. He escapes but returns to retrieve the box containing the elegant new shoes that he left behind in his haste to depart. There he discovers that Koldunov, wearing the shoes, has shot himself in the head. However, as I hope to show, there is rather more to this longish (30-page) story than this somewhat bald synopsis might suggest.

The action of the story takes place between the two performances of a play, set a

[47]

week apart, in which the story's eponymous hero appears. Like many of Nabokov’s protagonists, Lik is afflicted with a weak heart, and suffers on the night of the second performance a near-fatal attack, a "dress rehearsal of death" (to borrow V.'s phrase from Sebastian Knight). The play in which Lik is appearing is called L'Abîme or The Abyss, supposedly "by the well-known French author Suire" (Tyrants Destroyed, 71), and this title, together with the fact that, as the narrator parenthetically notes, "only two [performances] were scheduled" (78), suggests that the story may be more than the straightforward naturalistic study in exile and alienation it first appears. For the two Abysses of "Lik" invite interesting comparison with the favorite Nabokovian notion of the twin "abysses" of pre-natal and post-mortal eternity, as formulated in Speak, Memory and elsewhere. Nabokov's autobiography begins with the observation that "The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for." Likewise, in Bend Sinister Adam Krug wonders why we regard our retrospective eternity with less fear than our prospective one, and suggests that what we are trying to do when we equate the two "is to fill the abyss we have safely crossed with terrors borrowed from the abyss in front, which abyss is borrowed itself from the infinite past" (193). Similar statements can be found in The Gift, Pale Fire, and Ada.

[48]

The implication appears to be, as far as "Lik" is concerned, that Lik will not survive the second performance of The Abyss. This idea is borne out by a number of other details in the story. Lik believes he is soon to die, for example, and that his death will occur on stage, though he senses that such a death will transform him, elevating his shabby émigré existence ’’into the actual world of a chance Play, now blooming anew because of his arrival" (78). In an ironic variation on the well-trodden "life is a stage" tradition, Lik regards his stage-life as an idealization of his "real" existence, and death as more authentic than life—a typically Nabokovian inversion recalling Cincinnatus' distinction between the illusoriness of waking life and the reality of dreams in Invitation to a Beheading, or the "real lives" of Sebastian Knight and Luzhin in fiction and chess. Thus, Lik feels that "if death did not present him with an exit into true reality, he would simply never come to know life" (80). This comically paradoxical formulation of the death-in-life condition in which Lik feels himself trapped is enhanced by the associations contained in his name: the narrator remarks that the stage-name Lik has chosen for himself is an acronym of his initials meaning "countenance" in Russian and Middle English ("appearance" in the earlier version of the story collected in Nabokov’s Quartet), but Nabokov was doubtless also aware that Lik means "corpse" in Old Saxon, Norwegian, Swedish, etc.

Following Lik's heart attack shortly before the second performance of The Abyss, he again identifies his anticipated death with

[49]

the prospect of his entry upon the stage: "The thought of death coincided precisely with the thought that in half an hour he would walk out onto the bright stage and say the first words of his part" (98). The suggestion seems to be that his appointment at the theater for the final performance of The Abyss and his anticipated appointment with death will coincide . Such an interpretation helps to explain Nabokov's remarks, in his introductory note, that the story "attempts to create the impression of a stage performance engulfing a neurotic performer though not quite in the way that the trapped actor expected when dreaming of such an experience."

Lik's ultimate fate is not disclosed, since the story ends before the second performance of the play begins. Like Cincinnatus and a number of Nabokov’s other protagonists, he is imprisoned between the two abysses in a world of mere illusion. And except for momentary glimpses beyond (Lik’s idealized stage-life, Cincinnatus' dreams), this world of illusion is all they can ever know.

Finally, one wonders about the name given by Nabokov to the invented author of The Abyss. In view of the story's "shoe" theme, it may be worth noting that suire in Old French is a variant of suor, meaning "shoemaker."

Corrigendum: In an earlier note on Transparent Things ("Person's Regress," Nabokovian 15, 18-20), I mistakenly attributed to Baudelaire the quotation "Je me souviens, je me souviens de la maison où je suis né," which Nabokov/R. attributes to "Goodgrief" (Transparent Things, 94). Actually, the quote.

[50]

in its original English, is from the opening of Thomas Hood's poem "I remember, I remember." The choice of "Goodgrief" as a mask for Hood may be partly explained by the equivalence of the g and h consonants when transcribed in Cyrillic (cf. the wordplay on Gerald Emerald/herald in Pale Fire, note to line 741, and hamlet/Gamlet in Ada, p. 35).

— Robert Grossmith, University of Keele, England

NIKOLAI GOGOL: Selected Passages

The year-long streak of Nabokov publications in the U.S.S.R. culminated in January, when the Moscow Magazine printed The Luzhin Defense practically intact (proving wrong my pessimistic prognosis in The Nabokovian, 17). It had been preceded by an excerpt on chess problems from Other Shores (section 4 of Chapter 13), where suspension dots camouflaged the extraction of a sentence in which Nabokov blasts en passant the drab Soviet school of chess composition: if printed, it would have contradicted the efforts of Fazil Iskander (who wrote the introduction) to recommend Nabokov as a politically neutral person ("We criticize ourselves much harsher"). This was followed by the publication of two batches of Nabokov's sundry poems, "To Prince Kachurin" being the only poem mangled thoroughly.

Translation, however, is the most effective tool for caponizing a literary work employed by the Soviet censorship over the years to glib perfection. Unwanted passages can be easily mitigated, modified, or simply

[51]

omitted in translation. The April issue of the New World magazine (Moscow) contains a Russian version of the entire Nikolai Gogol. It is prefaced by Sergei Zalygin, chief editor, who tries to justify the publication of the book on its artistic merit and at the same time to point out Nabokov's limitations as an "elitist stylist", a routine strategy remindful of that hapless Bulgakov announcer who introduced a certain black magician by promising the discreditation of all his tricks. Zalygin speaks highly of what he calls Nabokov' s "exquisite style", which, he muses, Nabokov must have owed to his "aristocratic schooling". Here is one of his compliments: "Every word in his prose has its own place, and you can't move it one centimeter left or right, let alone up or down" [p. 173). But then he catches himself wondering whether the best "Russian classics", namely Tolstoy, Dostoevski, and Chekhov, would have retained enduring glory if they had adopted such a refined, polished, frail manner of writing, and answers his query in the firm negative. In fact, Nabokov's much too elegant style, continues Zalygin, "alienated our artist not only from the Russian folk language but also from the language of the masses" [ne tol'ko narod-nogo, no i massovogo yazyka], an interesting pronouncement.

At the bottom of that riotous piece is a footnote which says that in spite of a "series of inaccuracies that Nabokov committed" in his Gogol the editors have decided to let them stay uncorrected. This statement was meant, perhaps, to hypnotize the reader into thinking that what followed was an exact rendition of the original; however, even a superficial

[52]

examination revealed several local resections. I had neither the time nor the inclination to check the translation thoroughly but I assumed that the most troublesome for the Soviet editors chapter would be the one on poshlost'. Indeed, the passage

Ever since Russia began to think, and up to the time that her mind went blank under the

influence of the extraordinary regime she has been enduring for these last twenty-five years

... (the 1961 ed., p. 64)

was dropped in translation. And in

Propaganda (which could not exist without a generous supply of and demand for poshlust)

fills booklets with lovely Kolkhos maidens and windswept clouds [67]

the phrase in parentheses is rendered as "which cannot exist without a generous measure [bez shchedroj doli] of poshlost'" [NW, p. 197]. There are some curious omissions and alterations in other sections of the book as well. The sentence

No Tsar could break this backbone [the Russian democratic public opinion] (it was snapped

only much later by the Soviet regime) [127]

is excised completely, while "... the first symptoms of civic minded literary criticism which was to result in the ineptitudes of Marxism and Populism..." [29] is serenely transformed into the "criticism … that ultimately degenerated into the inane writings of

[53]

populists of various kinds” [NW-185, my emphasis].There are other small cuts, some more, other less baffling. They also seem to have left out consistently passages that they found too obscure or unimportant (see, for example, top of p. 80 of the original).

The translator, Mrs. E. Golyshev, is a ranking Soviet literary figure who has been entrusted with sensitive translating jobs before (Falkner, Hemingway, McCullers, Arthur Miller). I found her translation on occasion resourceful and bold but often imprecise, with lapses into the very massovyi yazyk the absence of which in the original Zalygin bemoans . She navigates around some difficult quodlibets while levigating others into a smooth naught, and some of her mistakes are awfully bizarre. The queerest one among those I spotted is on page 195, where Nabokov’s "dark stratagems and incalculable dangers (beautiful word, stratagem - a treasure in a cave)" [59] yields an arrant galimatias: "...the result of dark intrigues, ineffably dangerous (a beautiful world, an intrigue... a treasure in a cave)" [...rezul'tatom temnykh intrig, neskazanno opasnykh (prekrasnyi mir, intriga... sokrovische v peshchere].

One will remember that in the Soviet Union translation is a coveted way of making a living and is therefore an ugly world of ineffable intrigues, and that the translator is the first and often the most ruthless pruner of his work, so much so that I am not at all certain that the official censor, who read the MS after the New World in-house censor had combed it after Mrs. Golyshev had thinned it, had much left to cut out.

— Gene Barabtarlo, University of Missouri at Columbia

[54]

Zembla in the League of Nations

This summer I received a letter from a Mr. Eugene Shikhovtsev, who lives in Kostroma, USSR (some 200 miles NE of Moscow) and evidently reads with some regularity The Nabokovian through the good offices of its editor. He kindly sent me a curious note he had detected in the Paris émigré daily The Latest News [Poslednie Novosti] of July 30, 1939, asking me to translate and publish it. Here goes.

The Republic of Zembla

"The [London] Daily Telegraph recalls the first days of the League of Nations, when each nation was entitled to five seats for its delegates. Those who were not members of the delegation could occupy the peripheral seats [na bokovykh mestakh—Mr. Shikhovtsev notes the calembour on our author's name] where one could see or hear nothing.

M. Daniele Varè, a member of the Italian secretariat, decided to take the vacant seats behind the Venezuela delegation for his compatriots. He sneaked into the Assembly Hall at night and on a placard where the name of a country was to be displayed, wrote 'Zembla.'

On the following day, pundits cast one quick glance at the placard and nodded with significance, 'Zembla, of course.’ And so the five delegates of the 'Republic of Zembla’ sat there through the entire session, and it occurred to no one that there was no such republic and that its representatives were of pure Italian stock.”

[55]

I could not find the original Daily Telegraph article, but then Professor Priscilla Meyer, of Wesleyan University, referred me to an article by Peter Steiner entitled "Zembla: A Note on Nabokov’s Pale Fire" (in Russian Literature and American Critics, ed. K.N. Brostram, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1984, 265-272), which quotes not only the original text (in the DT of November 28, 1935, not 1939) but also an even more interesting piece in Fortune magazine of December, 1935, 60-62. I realized at once that the Russian compilation drew from both sources while it acknowledged only the earlier one. Varè stealing into the hall at night and the unstirred international everts are mentioned apparently only in the magazine version. Professor Steiner further quotes a most curious continuation of the story in Fortune ("...one can only regret that the League has outgrown Zembla ... a lovely country ... one can sit and dream for hours of its mountains and lakes, its coy princesses and ardent courtiers, and most of all its busy diplomats, so loyal to their young king ... a natural ally of Graustark where all of us spent our youth..."), mentions a book of Daniele Varé memoirs Laughing Diplomat (London, 1938), and provides elegant commentaries and parallels. He is unaware, however, of the Russian émigré digest of the two articles; in fact, he admits that the possible connection between Varè's practical joke and Nabokov's Zembla is so asthenic that it can be projected but hardly sustained. Mr. Shikhovtsev's finding may well be the missing link that suddenly reinforces this connection. Indeed, if Nabokov knew the anecdote at all he probably read it in the Latest News which he must have occasionally unfolded during the

[56]

summer of 1939, when he tweaked the nose of Adamovich, the paper's literary critic, in a famous hoax crowned by the publication of "Vasili Shishkov" in the September 12 issue of the LN. And if he missed the report, well, then the coincidence of time (Solus Rex in progress), place (Paris), matter (the quid quo pro, the utopia, the whiff of the Pale Fire Index in that vacant space for Zembla behind Venezuela) would be of such wonderful complexity and nearly perfect fit as to make it the kind of delightful footnote to certain Nabokovian theories of art that he himself was fond of procuring. In any event, Mr. Shikhovtsev ought to be congratulated on his splendid discovery, the more so because merely to get hold of an issue of The Latest News in Kostroma (or, for that matter, anywhere else within the USSR) is much more difficult than to locate the brochure The Tentative Staff of the Kostroma Province (St. Petersburg, 1778) in the Liberty University Library at Lynchburg, Virginia.

— Gene Barabtarlo, University of Missouri at Columbia

Squirrels

The squirrel has an important role to play in Pnin, as has been pointed out by Charles Nicol ("Pnin's History," reprinted in Critical Essays on Vladimir Nabokov) and developed thereafter by William W. Rowe ("Pnin's Uncanny Looking Glass," in A Book of Things about Vladimir Nabokov). In Speak, Memory we can read about its origin. In chap-

[57]

ter seven we see how Nabokov, emerging from a "trance," finds himself seated on a "bench in the park" where the "greenish flora" has been replaced by "violet tints." The trancelike state was caused by the intense searching for the solution to the problem: how to finish a poem properly. The next day he finds at the same place "a farmer and his son, who were similarly diverted by the sight of a young cat torturing a baby chipmunk—letting him run a few inches and then pouncing upon him again. Most of his tail was gone, the stump was bleeding. As he could not escape by running, the game little fellow tried one last measure: he stopped and lay down on his side in order to merge with a bit of light and shade on the ground, but the too violent heaving of his flank gave him away."

The coincidence of the feverish artistic struggle to solve the problem of the universe (in a poem) and the presence of an innocent squirrel is quite similar to the situation which befalls Pnin in Whitchurch "seated on a bench in a green and purple park." The squirrel is, at least for this moment, redeemed by the artist and is peacefully nibbling at a peach stone (24-25). The torturing re-enters later in the novel when we see how Mira Belochkin (belka is Russian for squirrel) is destroyed in a German "extermination camp" (135). The same exchange between beloved girl and squirrel is encountered in Lolita. When humiliated and humbled Lolita is driven away by Humbert from the Enchanted Hunters where they have spent the night, H.H. describes his feelings "as if I were sitting with the small ghost of somebody I had just killed." Lolita remains silent for a long time until she draws

[58]

the reader's attention: "'Oh, a squashed squirrel," she said. "What a shame" (142). There is also a small squirrel in King, Queen, Knave, a present from Drayer to Martha during their courtship, but this only occurs in the Russian edition; in the English version a monkey is substituted, and its life also ends in destruction (Carl R. Proffer, "A New Deck for Nabokov's Knaves," in Nabokov: Criticism, Reminiscences, Translations, and Tributes).

— Gerard de Vries, Voorschoten, The Netherlands

[59]

ABSTRACT

"Vladimir Nabokov's Machineries. The Dynamic Interplay of Discourse and Story in Three of His Novels."

by Daniele Souton

(Abstract of a Dissertation for a Doctorat D'État, University of Montpellier, France.)

Characterized by the recurrence of an original narrative organisation, described by the writer himself as a machinery, and the remarkable homology of constitutive parts, Vladimir Nabokov's creation has authorised the analysis of a limited number of his novels.

The first part of the thesis deals with Bend Sinister and the fictional exploitation of the elaboration of a totalitarian language and of the circulation of a fantastic tale meant to bend those Vladimir Nabokov antithetically calls "the beloved", for "the be-lowed", to the tyranny of a surreality. So as to denounce it, the Nabokovian discourse doubles and burlesques the mad sociolect. A second part centers the treatment of two other novels, The Defense and Despair, on the description of the psychotic central character's system - that is to say, on his particular and very private interpretation of events - which brings him to his doom. For the ambiguous quality, respectively, of a passion for chess and of the meeting with a fake double, aggravates the disorders of an original disposition, leading Luzhin to suicide and Hermann to murder. A first encompassing intratextual

-59-

relationship binds to a social "tale" that is no longer totalitarian but compelling all the same, the individual psychotic reply. Because the latter is taken charge of by the Nabokovian discourse, there appears, in each novel and at its different narrative and linguistic levels, a quite complex interplay that engenders a remarkable narrative dynamic.

The critical awareness of creative necessities , ascribed by Nabokov to the mutual solicitation of a personal truth and its caricature, prompts the elaboration of a third and last part in which to consider this difficult dialectic and the superior game of a split subject; for this very quality paradoxically promotes unifying reality within the split fiction.

Such an achieved narrative technique rises to the level of metaphysics and the Nabokovian quest for "aesthetic bliss" engenders a quality of ethics qualified as aristocratic. Thus, the autonomous self-reflexive artistic work, examined at first as an organic system, is finally questioned in the legitimate hope of getting from it, as one would from a speculative work, valuable insights into man's nature, part and place in the world.