Download PDF of Number 22 (Spring 1989) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 22 Spring 1989

_______________________________________

CONTENTS

News by Stephen Jan Parker 3

The Train Wreck

by Vladimir Nabokov translation by Dmitri Nabokov 12

Annotations & Queries by Charles Nicol

Contributors: Marina Turkevich Naumann, Charles Nicol 18

VN in the USSR

by Stephen Jan Parker 26

Exclusive Evidence

by Gennadi Barabtarlo 30

Abusive Evidence

by Dmitri Nabokov 37

Abstracts

Galina De Roeck, "History as Fiction and Fiction as

History in Nabokov’s The Assistant Producer’" 40

Yvonne Howell, "Science (and) Fiction in ’’Lance'" 42

James F. English, "Mastery, Transcendence, and the

'Hegelian Syllogism of Humor' in Pale Fire" 44

[2]

Brenda K Marshall, "’Nabokov Would be Horrified':

Authorial Position in Nabokovian Criticism" 45

Charles Nicol, "The Gift and Related Works' 47

[3]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

All American rights to Nabokov's English language works are now held by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc. At least twenty titles are projected for publication, one per month, in the new Vintage International series of quality paperbacks. Most of these editions will differ slightly from all previous ones because they will incorporate corrections of previous typographical errors, dropped items and include all of the author's final corrections. The first six volumes scheduled to appear, beginning this spring, are Lolita (March), Pale Fire (April), Despair (May), Pnin (June), King, Queen, Knave (July), Speak Memory (August).

*

Mrs. Véra Nabokov has provided the following list of VN works received October 1988 - March 1989:

October — Kаmеmа Obskura (Russian). In Volga (USSR), No. 6-8.

December — La Verdadera Vida de Sebastian Knight, tr. Enrique Pezzoni. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama, "Biblioteca Nabokov."

January — Lolita, tr. Bekespal. Budapest, Hungary: Europa Konyvkiado.

January — Lolita, tr. Bekespal. Budapest, Hungary: Alapkiadas-Europa, bookclub edition.

January — "Solus Rex" (Russian). In Aurora (Leningrad), No. 6.

[4]

January —"Ultima Thule" (Russian). In Aurora (Leningrad), No. 7.

January — Habla Memoria [Speak, Memory], tr. Enrique Murillo. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama, second edition.

January — Talle Minne [Speak, Memory], tr. Lars Gustav Hellstrom. Stockholm: Forum.

February — "Muzik." In Ad Libitum, Sammlung Zerstreuung, No. 10. Berlin: Volk und Welt.

March — Lolita. New York: Vintage International.

*

The general membership of AATSEEL, at its December meeting in Washington. D.C., voted overwhelmingly to hold all future annual meetings at the same place and time as the annual MLA meetings. Since the MLA national convention this year will be in Washington, DC, AATSEEL will return to that city for its own national convention, and once again Slavists and Americanists will be able to participate in all sessions of the Vladimir Nabokov Society.

Two sessions are planned for MLA in 1989: (1) "Sexuality in Nabokov's Narrative,” chaired by Brenda K. Marshall (107 East Greenwood Avenue #3, Lansdowne, PA 19050) and (2) "Approaches to Teaching Nabokov," chaired by Zoran Kuzmanovich (Department of English, Davidson College, Davidson, NC 28036). The session at AATSEEL, "Nabokov as Critic," will be chaired by Galya Diment (Slavic Languages, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195).

Considering the split in locations, this year's AATSEEL and MLA sessions were well attended. At AATSEEL, "Nabokov's Poetics” was chaired by John Kopper (Dartmouth). Papers read were: "The Nature of

[5]

Science in 'Lance'," by Yvonne Howell (Michigan); "About Buying a Horse: Chess and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight," by B. Rush Barrett III (Yale); "History as Fiction and Fiction as History: Nabokov's The Assistant Producer',” by Galina de Roeck.

At MLA, the first session, "Nabokov and Contemporary Critical Theories", was chaired by Geoffrey Green (San Francisco State University). The papers read were: "'Nabokov Would be Horrified': Authorial Position in Contemporary Critical Theory," by Brenda K. Marshall (U of Mass, Amherst); "Preserving the Subject, Resisting the Text: Nabokov on Kafka," by Martina Sciolino (U of Southern Mississippi); "Mastery, Transcendence, and the 'Hegelian Syllogism of Humor’ in Pale Fire," by James English (U of Pennsylvania); "Nabokov and the Role of the Reader: Lolita's Challenge to Contemporary Theories of Literature," by Brian Richardson ( U of Washington).

The second session, "Nabokov and Others: Affinities and Arguments," was chaired by Ellen Pifer (U of Delaware). The papers read were: "Nabokov's Use of Shakespeare," by Samuel Schuman (Guilford College); "Humbert and Don Quixote," by Thomas Woodson (Ohio State U); "The Presence of Proust in Ada," Pascal A. Ifri (Washington U); respondent, Edith Mroz (Delaware State College).

*

Gene Barabtarlo has sent information concerning the "Vladimir Nabokov International Conference" recently held in Paris. "It was organized by 'The Russian Literary Centre’ and the Third Wave Publishing House, both headed by Alexander Glezer, poet, publisher, and collector and patron of the arts. It was in the basement hall of the Museum of Contemporary Russian Art (owned by Mme. Cochin, Glezer's wife), on March 12, from 2:30 to almost 8:00 pm, with one 10 minute break, in the presence of about

[6]

40 people, mostly local émigrés." The program, entirely in Russian, was:

— Alexander Glezer, introductory remarks

— Viktor Erofeev (USSR), remarks on the publication of VN in the USSR; including mention that he has been asked by a Moscow publishing house to edit a four-volume set of VN works with a projected printing of about 1,700,000 copies.

— IUrii Mamlev (France), "Sarcasm in Nabokov"

— Priscilla Meyer (USA), "The German Motif in VN's Writings of the 1920s"

— Galina Bovi-Kiziloff (Switzerland), sang "romances,” accompanied by guitar, from lyrics presumably by Nabokov

— Rene Guerra (France), reading his published article (1984) on The Event

— Sergei lUrienen (Munich, Radio Liberty), "Freud and Nabokov"

— Mikhail Epstein (USSR), 'Teaming for Nabokov" (largely a textual analysis of VN’s tropes)

— Gennadi Barabtarlo (USA), reading his translation of "A Forgotten Poet"

— Galina Bovi-Kiziloff, more guitar-accompanied "romances".

All of the talks were recorded for later broadcast by Radio Liberty. The proceedings are to be published in Russian in Almanac Sagittarius, No. 2, May 1989.

[7]

The following letter to the editor of Novyi zhumal (New York) deserves widest dissemination among Nabokovians in order to thoroughly clear the record:

July 4, 1988

Dear Sir:

Recently a friend called our attention to the poem, "Isakiy," which was published in Issue No. 167 (1987) of Novyi zhumal [The New Review]. Authorship of the poem is attributed to "Vladimir Nabokov" above the text, and, following the last line, its source is given as "the archive of A. Rovner."

If your review has a literary editor, he should have realized that "A. Rovner" was pulling his editorial leg, and that Nabokov could never have produced such vulgar trash, every line of which exudes ineptitude. Who is "A. Rovner”? Do you really believe that drivel of unknown provenance can be published and freely ascribed to the poet of your choice, be it Nabokov, or, say, Blok or Pushkin?

Had this poem been by Nabokov you would have been guilty of copyright infringement. Since, for anyone who has ever read Nabokov's poetry, it cannot even qualify as a bad parody, we demand that, in your next issue, you publish a prominently displayed retraction, explaining how such an "error" could have occurred.

We reserve the right to seek damages for the harm inflicted on Vladimir Nabokov’s memory and for the illegitimate use of his name.

(Signed, Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov, Dmitri Nabokov)

The text of the poem:

[7]

ISAKII

S devchonkami Likoi i Lipol

V sirenevyi utrennii chas

My vyryli v pliazhe pustynnom

Bol'shoi i shirokii barkas.My vlezli v korabl' nash pyzatyl.

IA vzial kapitanskuiu vlast'.

Kupal'nyl kostium polosatyi

Na machte zareial, kak snast’.Таk mnogo chudes est’ na svete!

Zemlia — neizvedannjri sad.

Poedem na IAby? — No deti

Shepnuli, sklonias’: — V Leningrad.Volna nabegavshego vala

Drozhala, kаk sinii opal.

Komanda surovo molchala.

A veter kosichki trepal.Po grebniam zaprygali baki.

Vblizi nad pustynei sedoi

Siiaiushchei shapkoi Isakii

Mirazhem stoial nad vodoi.Goreli pribezhnye meli.

I klanialsia nizko kamysh.

My dolgo v trevoge smotreli

Na piatna temneiushchikh krysh.I mladshaia robko skazala:

"Prichalim? Il’ net, kapitan?”

Sklonivshis' nad krugom shturvala.

Nazad povernul ia. v tuman.

[9]

Odds and Ends

— September 1 is the official publication date for Vladimir Nabokov. Selected Letters. 1940-1977, edited by Dmitri Nabokov and Matthew Bruccoli, published by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich/Bruccoli Clark. Weidenfeld will publish the British edition.

— Brian Boyd's chapter on VN's years in the Crimea, 1917-1919 ("Foretaste of Exile") won the Thomas Carter essay prize for the best essay in Shenandoah for this year. The piece appeared in the March issue.

— Dmitri Nabokov's "Close Calls and Fulfilled Dreams: Selected Entries from a Private Journal" appeared in the Fall 1988 issue of Antaeus.

— Rowohlt (Germany) is issuing a complete collection of VN works; Penguin (England) has a new Nabokov series; Bompiani Classic! (Italy) will issue a Nabokov collection of works; Anagrama (Spain) continues to expand its Biblioteca Nabokov collection.

— Ludmilla Foster produced a special Voice of America 90th Jubilee tribute to VN with the participation of Simon Karlinsky and Ellendea Proffer.

— On the current list of Russian editions of VN works available through Ardis: Ania v strane chudes, Blednyi ogon', Perepiska s sestroi, Pnin, Sobrante sochinenii, Vol I: Korol', dama, valet, Vol. VI: Dar, Vol. IX: P’esy, Vol. X: Lolita, Sogliadatai, Vesna v Fial'te, Vozvrashchenie Chorba. Also now available from Ardis is VN's English translation, The Song of Igor’s Campaign.

— Ardis has announced for publication in 1989: Gennadi Barabtarlo, Phantom of Fact: A Guide to Nabokov's PNIN, and Christine Rydel, A Nabokov's

[10]

Who's Who. A Complete Guide to Characters and Proper Names in the Works of Vladimir Nabokov.

— A special issue of Revya (Review] (No. 11, 1988), a Yugoslav journal for literature, culture, and social questions, published in Osijek, is devoted entirely to VN's prose. Selection, forward, chronology of VN's life and works, and general editing is by Magdalena Medaric. Contents: "The Potato Elf' (tr. Irena Luksic), "Bachmann" (tr. Irena Luksic), The Eye (tr. Irena Luksic), "Ultima Thule" (tr. Ratko Venturin), "That in Aleppo Once..." (tr. Zlatko Crnkovic), "Signs and Symbols" (tr. Nada Soljan).

— Pekka Tammi, University of Helsinki and Visiting Fulbright Scholar at the University of California, Santa Barbara, delivered a lecture, "Russian Subtexts in Nabokov’s Fiction," at the University of Missouri on April 5.

— Susan Elizabeth Sweeney forwards an amusing item from Amtrak Express magazine (October 1988). In an article on the photographer, Cartier-Bresson, the following passage occurs: "He (Cartier-Bresson] spent a year in New York in 1935, prowling the city but without taking photographs. Novelist Valdimer Nabokov was a frequent companion at this time, and in his memoirs, he relates that Cartier-Bresson loved to eat apple pie à la mode, because it was the cheapest and most nourishing dish available in America." (VN, of course, came to the USA for the first time in 1940, but maybe Valdimer was here earlier, Ed.]

— Gene Barabtarlo notes the following acknowledgment citation in Modem Critical Views: Vladimir Nabokov, ed. Harold Bloom: "'Parody and Authenticity in Lolita’ by Thomas R. Frosch from Nabokov’s Fifth Avenue, edited by J. E. Rivers and Charles Nicol,

1982."

[11]

— John Yewell (P.O. Box 1668» Palo Alto, CA 94302) is a letter carrier, an editor, a Nabokovphile, and a subscriber to The Nabokovian. He has just edited an anthology of short stories by letter carriers entitled. Men & Women of Letters. The stylish jacket of the volume shows the editor's desktop replete with carrier’s cap, typewriter, Jim Beam, writer's accoutrements, and volumes of books. Identifiable among them are Ulysses, Gravity's Rainbow, Pale Fire, The Dare by Sirin, and a volume simply entitled, NABOKOV.

*

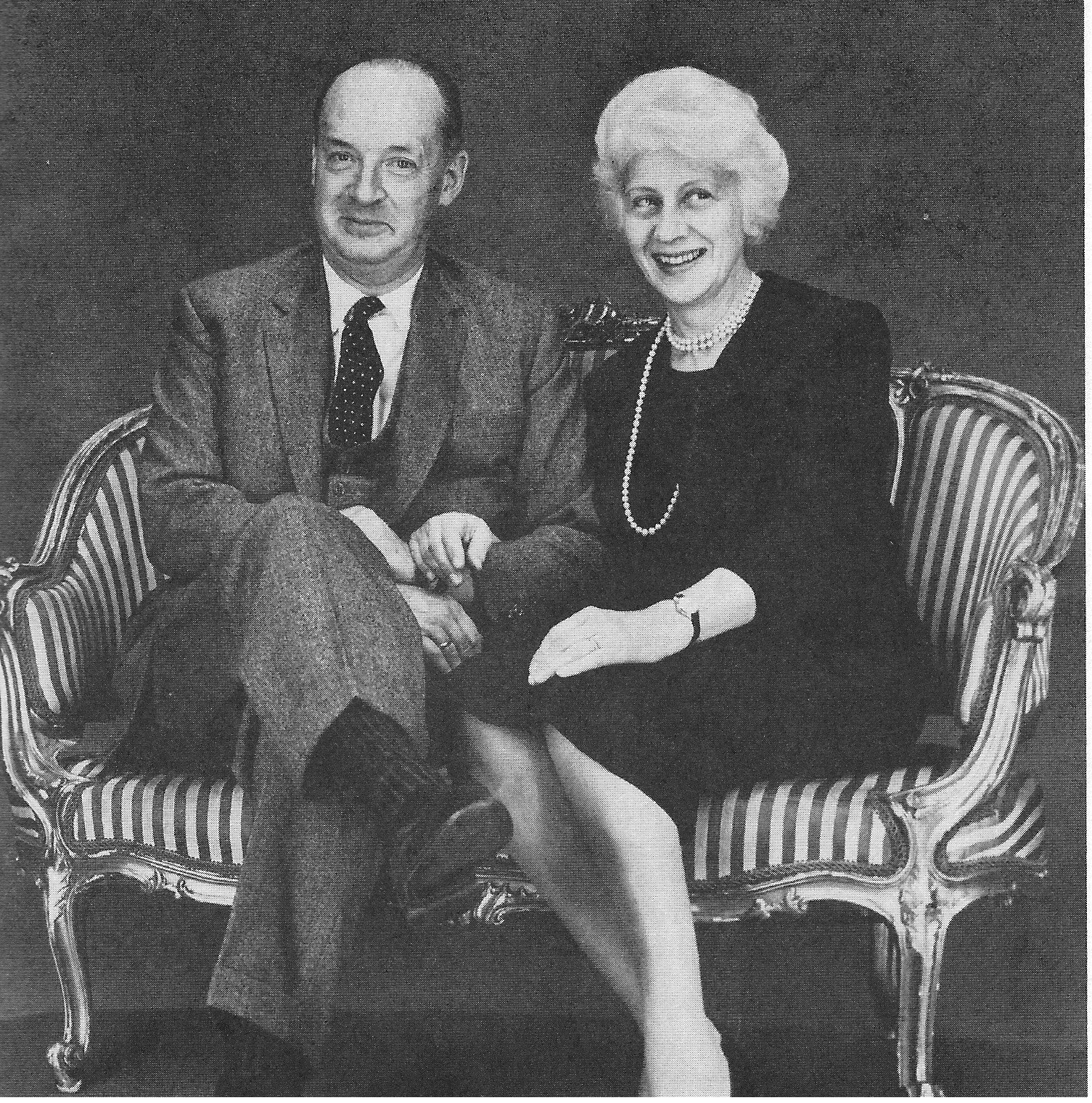

The photograph was provided by Mrs. Véra Nabokov. Credit is to Colin Sherborne, London, 1959.

*

Once again we complete the "News" segment by acknowledging the indispensable assistance of Ms. Paula Malone in the preparation of this issue.

[12]

The Train Wreck

Vladimir Nabokov (1925)Translated by Dmitri Nabokov

'Neath twilight’s vault, into the meadows,

enveloped in the toppled smoke,

at full career the cars are heading

behind the engine's fiery glow:the baggage car, locked tight, foreboding,

where trunks are piled on top of trunks,

where objects that have grown demented

awaken in the dark and clunk —then, in succession, the four sleepers,

the whole row paneled with veneer,

whose windows flash like mirrored lightning,

with fleeting, alternating fire.An early drowsiness makes someone

pull down a leather window blind,

and, 'midst the clattering and crackling,

the right refrain acutely finds.

[13]

Krushenie

V polia, pod sumerechnym svodom,

skvoz' oprokinuvshiisia dym

proshli vagony polnym khodom

za parovozom ognevym:bagazhnyi — zapertyl, zloveshchii,

gde sunduki na sundukakh,

gde obezumevshie veshchi,

prosnuvshis', bukhaiut vpot’makh —i chetyrekh vagonov spal'nykh

faneroi vylozhennyi riad,

i okna v molniiakh zerkal'nykh

chredoiu begloiu goriat.Tam shtoru kozhanuiu spustit

dremota, rano podospev,

i chutko v stukotne i khruste

otyshchet pravil'nyi napev.

[14]

Those not asleep don’t take their eyes off

the ceiling’s vague concavities,

where swings, beneath dim-filtered lamplight,

the tassel of a sliding shade.A trifling thing — a bolt untightened,

and, suddenly, beneath one's head,

the clinging flange, the speeding iron,

jumps off the evil-fated rail.And, up and down the nighttime flatland,

the telegraph beats like a heart,

and people hurtle on a handcar,

their lanterns lifted in the dark.A sorry thing: the night is dewy,

but here there’s wreckage, flame, lament....

No wonder that the driver’s daughter

an eerie dream of ballast dreamt,in which around the bend came howling

a hurtling multitude of wheels,

and to its doom a pair of angels

a giant locomotive drove.

[15]

I kto ne spit, tot glaz ne svodit

s tumannykh vpadin potolka,

gde pod skvoziashchei lampoi khodit

kist' zadvizhnogo kolpaka.Takaia malost' — vint nekrepkii,

i vdrug pod samoi golovoi

chugun begushchii, obod tsepkii

soskochit s rel'sy rokovoi.I vot po vsei nochnoi ravnine

stuchit, kak serdtse, telegraf,

i liudi mchatsia na drezine,

vo mrake fakely podniav.Takaia zhalost': noch' rosista,

a tyt — oblomki, plamia, ston...

Nedarom dochke mashinista

prisnilas' nasyp', strashnyi son:Tam, zavyvaia na izgibe,

stremilos' sonmishche koles,

i dvoe angelov na gibel'

gromadnyi gnali parovoz.

[16]

The first of them, who manned the throttle,

advanced his lever with a smirk,

as, incandescent features gleaming,

he peered into onrushing murk.The second one, the winged fireman,

with steely, scintillating scales,

untiringly, with blackened shovel,

hurled coal into the firebox blaze.

Copyright © 1979 Vladimir Nabokov Estate English version Copyright © 1988 Dmitri Nabokov

[17]

I pervyi nabliudal za parom,

smeias', perestavlial rychag,

siiaia peristym pozharom,

v letuchii vgliadyvalsia mrak.Vtoroi zhe, kochegar krylatyi,

stal'noiu cheshuei blistal,

i ugol' chernoiu lopatoi

on v zhar bez ustali metal.

[18]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

[Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov's works will be to the most recent hardcover U.S. editions.}

NOVEL CAT CONNECTIONS

I should like to make some observations concerning the topic Felis Catus Nabokovi. On these pages (16:14-15), Susan Sweeney drew our attention to May Sarton’s novel (as it has been categorized by its publisher) The Fur Person (1957), reprinted in 1978 with a preface of direct interest to Nabokovians.

In Sarton’s opening remarks she engagingly confirms that the Fur Person is really her beloved cat Tom Jones, named of course after Henry Fielding's foundling. In Spring 1952, when Sarton sublet her Cambridge MA home to none other than the Nabokovs, Tom Jones remained there "as a cherished paying guest” (8). Sarton explains the significance of this literary association thus:

My study at Maynard Place was at the top of the house; a small,

sunny room, one wall lined with books, and on the windowed side

a long trestle table and a straight chair. Nabokov removed this

austere object and replaced it with a huge overstuffed armchair

where he could write half lying down. Tom Jones soon learned

that he was welcome to install himself

[19]

at the very heart of genius on Nabokov’s chest, there to make

starfish paws, purr ecstatically, and sometimes — rather

painfully for the object of his pleasure — knead. I like to imagine

that Lolita was being dreamed that year and that Tom Jones'

presence may have had something to do with the creation of that

sensuous world. At any rate, for him it was a year of grandiose meals

and subtle passions. (8)

It is in Pale Fire, however, that "the frame house between / Goldsworth and Wordsmith on its square of green” (34) rented by Charles Kinbote surely echoes Nabokov's Maynard Square home. And Andrew Field states that 'Tom Jones eventually came to live in Pale Fire'“ (VN 268). We recall that when Kinbote moves in, he discovers, "among various detailed notices affixed to a special board in the pantry,... the diet of the black cat that came with the house," a rotating menu which he ignores: "All it got from me was milk and sardines: it was a likable little creature but after a while its movements began to grate on my nerves and I farmed it out to Mrs. Finley, the cleaning woman" (84-85).

Of course, Kinbote's version is completely at odds with the reported love and tenderness felt between Tom Jones and the Nabokovs. According to Field, "when Tom became sick they took him to the veterinarian and visited him there regularly until he was better" (268). And according to Sarton, at a tea-time reunion some years later at Cambridge's Ambassador Hotel between the visiting Nabokovs, Tom Jones, and his two ladies, "a dish of raw liver cut into small pieces was laid on the floor for the hero of the occasion” by the host Nabokovs (9). Another change in the transit from Sarton’s novel to Nabokov’s is that while Fur Person is tiger striped, with a white shirt front and a white- tipped tail, Kinbote’s cat is black. Sarton's literary portrait is graphically confirmed by David Canright’s many delightful illustrations. Could the alteration be the result of artistic license or have there been cats other than Mr.

[20]

Jones who have prowled even more stealthily from Nabokov's real life into his fictional world?

— Marina Turkevich Naumann, Princeton University

DATING PROBLEMS IN "THE CIRCLE"

Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev is, of course, the protagonist of The Gift (Dar). The short story "The Circle" (“'Krug") views the Godunov-Cherdyntsev family from a different perspective, that of the Leshino village-schoolmaster’s son Innokentiy, who has a one-night affair with Fyodor's sister Tanya in the summer of 1914 and meets her again by chance a number of years later in Paris. Nabokov’s introduction to its English translation twice states that the story was written in 1936, further explaining that the chance reunion also takes place in that year. Nabokov's introduction begins as follows: "By the middle of 1936, I must have completed at least four-fifths of [The Gift’s] last chapter when a small satellite separated itself from the main body of the novel and started to revolve around it." Then Nabokov conflates the chronology of the two works, in the process giving a date that perhaps not even a careful reader of The Gift could establish for himself: "the action of The Gift starts on April 1, 1926, and ends on June 29, 1929 . .. [Tanya's] marriage takes place in Paris at the end of 1926 ... her daughter is born three years later, and is only seven in June 1936, and not ’around ten,’ as Innokentiy, the schoolmaster's son, is permitted to assume (behind the author's back) when he visits Paris in ‘The Circle."' These statements appear to be mostly incorrect; for example, Ronald E. Peterson, in a prior issue of the Nabokovian (9: 36-40), has argued that The Gift actually starts in 1925. The only really accurate observation is that the story certainly does "revolve" around the novel—an observation to which I will return.

[21]

In fact, as listed in Juliar's bibliography, "The Circle” was published not in the middle of 1936 but on 11 and 12 March 1934. The nearest guess I can make to when it spun off was during the middle of The Gift's second chapter, when Fyodor's mother visits him in Berlin, gives him a photograph of Leshino, and discusses Tanya's forthcoming marriage to a man of dubious character on the rebound from an unhappy love affair.

The fact that the story was published early in 1934 leads to even greater problems in conflating the age of Tanya’s daughter than those breezily dismissed in Nabokov’s introduction. In 1934, Tanya's daughter would be, according to his chronology, only five (or six, in Peterson's chronology), and it is hardly conceivable that Innokentiy would mistake her for a ten-year-old. The explanations I can conceive are not very satisfactory for those who like things neat: Nabokov was very careless about the chronology of his characters; or he did not check back with "The Circle," perhaps not readily at hand when he reached the end of his novel; or the story and the novel somehow exist in different time-frames, not just different perspectives on the same material.

An interesting example of Nabokov's attempt to revise his work after the fact can be found here. "The Circle" itself is vague about all dates except those of the summer of 1914 — and even those are given in old style. The only internal clue we have to the date of the reunion of Innokentiy and Tanya in Paris is found, characteristically, hidden in a metaphor on the story's last page:

Suddenly Innokentiy grasped a wonderful fact: nothing is lost,

nothing whatever; memory accumulates treasures, stored-up

secrets grow in darkness and dust, and one day a transient visitor

at a lending library wants a book that has not once been asked

for in twenty-two years.

[22]

The book that has not been asked for in twenty-two years is, of course, Innokentiy’s relationship with Tanya. But 1614 plus 22 is 1936! According to the English version of "The Circle," then, the chance reunion actually does take place in 1936, as Nabokov said it did. Is it possible that this story, published in 1934, actually ended with events in 1936? No, alas; if we return to the Russian version we find

i vot kto-to proezzhiy vdrug trebuet i bibliotekarya

knigu, nevydavavshuyucya dvadtsat’ let.

In translating the story, then, Nabokov decided that his own recollection was more accurate than the text itself and added an extra two years to that book's darkness and dust; I hope that in some future edition the "twenty-two years" of the English version will be changed back to twenty.

The main technical point of 'The Circle" is, as its self-referential title points out, its circularity: the last sentence of the story is also the sentence that should appear before its first. This circularity is also a preeminent feature of The Gift, as nicely stated by D. Barton Johnson:

Like the Chernyshevski biography. The Gift displays the form

of the legendary snake swallowing its own tail. The novel

relates a period from the life of the young writer-protagonist

and ends with him outlining a novel based on the same events.

Contained within this all-encompassing master circle are a number

of episodes, some of which have their own circular shape. Most

prominent among these is, of course, the Chernyshevski biography.

A lesser example is Fyodor's book of poems about his childhood which

opens with a poem about a lost ball and concludes with a poem in

which the ball is found. The

[23]

story of Yasha . . . is aptly referred to as "a triangle inscribed in a circle."

The tale of Fyodor's explorer father, lost and presumed dead, is also

ultimately circular in shape. Another self-reflexive aspect of The Gift

is to be found in its inclusion of Fyodor’s reviews of his own work ...

In some sense all of the novel’s episodes are encompassed within its

circular framework. (Worlds in Regression, 95)

In relating the circles of "The Circle” to the circles of The Gift, we discover another dimension to the story’s circularity. For "The Circle" encompasses The Gift in its dates, being composed essentially of two episodes, one in the summer of 1914, the other in early 1934. These episodes neatly enclose the three years described in The Gift, whether they are 1926-1929 or 1925-28, and bind the novel within its curve. And this is my personal vision of "The Circle": a sort of city wall encompassing The Gift within its environs and defining the novel's possible space at a stage early in its composition.

—Charles Nicol

BANANA QUERY

I noticed an interesting recent reference to Nabokov

But language instruction is sometimes effectively enlivened

with humor. Vladimir Nabokov no doubt thought so. A Russian

textbook he wrote for English speakers begins, "Hello, I am the

doctor, and this is a banana." (Thomas Swick, 'Talking in [Foreign]

Circles," Travel & Leisure May 1988: 98-100)

The article was about learning a foreign language. I have written to Mr. Swick, but he can't remember

[24]

where he read the anecdote, although he suspects it was in a memoir or remembrance, possibly by Nabokov.

The only reference that I've uncovered to fruit and the Russian language is in an article by Nabokov in the Wellesley Magazine 29:4 (1945): "A Russian vowel is an orange, an English vowel is a lemon" (191). He then adds, probably with tongue in cheek:

I strictly avoid the humorous touch when dealing with my classes,

but such-like explanations, which are merely meant to stress the

anatomical differences between the two languages, oddly enough

provoke a ripple of laughter, when all I ask for is a bland smile of

the Cheshire cat type.

I’d appreciate any information about the anecdote quoted by Swick.

—Jim McWilliams, University of Nebraska

(Maddeningly familiar, but I couldn't help. Help. — CN]

[25]

[26]

VN in the USSR

by Stephen Jan Parker

Though news from the USSR reaches us irregularly, it is evident that publication of VN’s works and commentary on them continues to flourish, and that journals and publishing houses are vying for the number and importance of VN works published. Christopher Hope reports that in the USSR "by common consent the bestsellers are: Children of the Arbat by Anatoly Rybakov; Nabokov's The Gift and Mary — indeed anything else by him" (The Sunday Times. Books, 2 April 1989). Recent items:

— We recently received a rush order for a full set of back issues and a current subscription to the The Nabokovian from The Library of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR The order reads: "[the set] is needed very much by the specialists of the Pushkinskii Dom/the Institute of Russian Literature collections."

— A two-record album entitled V. Nabokov, Drugie Berega, Stikhi i Proza, Chitaet Vadim Maratov [V. Nabokov. Other Shores. Poems and Prose. Read by Vadim Maratov] was issued by Melodia, 1988 in 4,160 copies, price 1 ruble, 45 kopeks; jacket copy and composition author Lidia Libedinskaia, producer A. Nikolaev.

— "Russkii metaroman V. Nabokova, ili v poiskakh poteriannogo raia" (V. Nabokov's Russian metanovel, or in search of lost paradise] by Viktor Erofeev and "Interviu, dannoe Alfredu Appeliu" [translation of Alfred Appel Jr.'s interview with VN in Dembo ed., Nabokov: the Man and His Work], translation and introduction by M. Meilach, notes by A. Dolinin. Voprosy literatury. No. 10, 1988.

[27]

— Poems ("On the Train," "A Morning," "A Ski Jump," In Paradise," "What Happened to Memory Overnight") and article by M. Shapovalov. Den' poezii anthology, 1988.

— Stories ("The Aurelian," "Spring in Fialta," "Cloud, Castle, Lake," "Terror," "The Thunderstorm") and extract from Z. Shakhovskaia, In Search of Nabokov. lUnost, No. 11, 1988.

— One poem (title not known). Peterburg v russkoi poezii ed. M. V. Otradin, 1988.

— One poem ("A Forgotten Poet'). Smena 88, 1988.

— Stories ("The Return of Chorb," "The Port," "A Letter that Never Reached Russia," "Christmas," ’Terror," "The Reunion," "Music," "Perfection") and an article by A. Muliarchik with photograph. Literatumaia ucheba. No. 1, 1989.

— Play ("The Pole") and article by N. Tolstoy. Russkaia literatura, No. 1, 1989.

— Pnin [The Ardis Russian edition, tr. Gene Barabtarlo and Véra Nabokov]. Inostrannaia literatura. No. 2, 1989.

— Stories ("A Bad Day," "Orache," "A Dashing Fellow," "A Busy Man," "The Aurelian," "Perfection," "A Slice of Life") and Raevsky, "Remembering Nabokov." Prostor, No. 2, 1989.

— Play ('The Waltz Invention"). Novyi mir. No. 2, 1989.

— The Eye, stories ("A Reunion," "A Slice of Life," "A Russian Beauty") and article, "Coloured Dreams." Moldavia literatumaia, No. 8, 1989.

— Lolita [VN's translation]. Inostrannaia literatura. Nos. ?, 1989 (its publication has been confirmed by several people without the exact citation].

[28]

*

Of direct concern to members of the Vladimir Nabokov Society is the following communication from John Kopper (Department of Russian, Dartmouth College; Hanover, NH 03755);

"I attended a Nabokov evening in Leningrad's Dvorets molodezhi in July, and a second evening on September 30. The latter was organized by the Leningrad Fond kul'tury, and was held in the former Tenishev Academy, now the Institut muzyki i kinematografii on ul. Mokhovaya. The hall in which the event took place was apparently the gymnasium of the Tenishev Academy in Nabokov's time. Nikita Alekseevich Tolstoy chaired the literary evening, which included presentations by Vladimir Gerasimov and Ivan (Nikitich) Tolstoy, I also addressed the gathering briefly. A wealth of biographical material from Nabokov's Russia years was introduced, and reports were made on progress in building the collection of Nabokov memorabilia at Rozhdestveno, as well as in placing a memorial plaque on the wall of the former Nabokov townhouse on ul. Gertsena (form. Bolshaya Morskaya). I promised the participants that I would report on the evening to The Nabokovian, and relay their request for 'obshchestvennaya pomoshch" (public assistance). Soviet Nabokov fans need not so much money for the restoration of Vyra and the hanging of the plaque as pressure from the international community of Nabokov scholars to have Nabokov recognized as a major Russian talent. Apparently bureaucratic ignorance, rather than antipathy, is now slowing the commemoration ventures of Nabokov's Soviet admirers."

In a subsequent letter. Prof. Kopper goes on to say: "My sense is that "public assistance" offered to Soviet Nabokovians might take a couple of forms in the short run. First and foremost is the need to establish contact. I would suggest letters from the VNS, expressing

[29]

interest in establishing ties with Soviet Nabokovians, suggesting that they might consider forming a Soviet chapter of the VNS, and requesting help in identifying Nabokovians who would be interested in joining either such a society or — if no organization is founded there — the VNS directly. And if the political climate still makes international membership a risky venture — unlikely-at least the VNS could get a list of names of people to receive publications and announcements.

In the longer term, Soviet Nabokov scholars desperately need certain documents not coming out in the USSR yet; Nabokov's letters, published photographs relating to his life, and certain literary works, especially the plays. Furthermore, once a group of Soviet Nabokovians has been identified, the VNS could encourage Western scholars setting up Nabokov panels/conferences—and producing journal issues or essay collections devoted to Nabokov—to consider inviting Soviet colleagues. Travel abroad by invitation to meet other Nabokovians would probably be the greatest single boon one could offer Soviet Nabokov scholars."

Following from Prof. Kopper’s suggestions. The Nabokovian has written to several Soviet VN admirers indicating (1) we would welcome their membership in the international VNS; (2) we would like to know what materials they need; (3) we would like to know what we can do to support their efforts in regard to Vyra and the memorial plaque; (4) we would like to know what else we can do in the way of "public assistance”; and (5) we would like to have a list of Soviet Nabokovians with whom we can establish contact.

The matter is an important one and the editor encourages comments and suggestions from readers, sent either to The Nabokovian or to Julian Connolly, President of the VNS (Slavic Languages & Literatures, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22903).

[30]

EXCLUSIVE EVIDENCE

By Gennadi Barabtalo

The Russian version of Nabokov's memoir. Other Shores (1954), has been brought out recently in the U.S.S.R., in two issues of the Moscow monthly Nations' Friendship (Druzhba Narodov, 5 and 6, 1988). Naturally, the book is unprintable there in toto even at the time of general censoring lenity. I learned of the publication's many excisions, marked by suspension dots in elbow brackets, from a note in La Реnsée Russe, a Russian émigré weekly (of June 17, 1988, p. 10), which listed major omissions. I endeavored to collate the Soviet text with the original; here are my findings.

The publication is prefaced by a mediocre overture by Andrey Chernyshev who, unlike some of his predecessors, bends no nails in order to cast Nabokov as a politically indefinite Russian patriot whose exile was a tragic mistake, but says instead that, being "an aristocrat by origin, a convinced individualist, [Nabokov] did not accept the new reality — the Soviet Union and its difficult and heroic destiny". In the same nimble fashion he dims the fact of censor's meddle by hinting at it in a swift demure clause only syntactically related to the main sentence it severs: "The book Other Shores — which is published here with some abridgement — is, in a way, a key to Nabokov's artistic prose.” Below are all of those "nekotorye sokrashcheniia", both in transliterated Russian, for the sake of the wronged Soviet reader (there are more and more reports that The Nabokovian does find its way to the U.S.S.R.), and in English. Where the two versions are at variance, I supply my translation. Pagination is given first by Russian, then by Soviet (issue No.6 containing all the excisions), and finally by English (1966) edition.

Text in italics was cut.

[31]

1. R121/S87/E131

Kakoi-to bol’shevitskii chasovoi, kolchenogii duren's ser'goi v odnom ukhe...

[A Bolshevik sentry, a bow-legged blockhead with an earring in one ear...]

2. R210/S118/E241

V amerikanskom izdanii etoi knigi mne prishlos' ob"iasnit' udivlennomu chitateliu, chto era krovoprolitiia, kontsentratsionnykh lagerei i zalozhnichestva nachalas' nemedlenno posle togo, chto Lenin i ego pomoshchnikci zakhvatili vlast'. Zimoi 1917-go goda demokratiia eshche verila, chto mozhno predoturatit bol'shevisiskuiu diktaturu

[In the English edition of this book, I had to explain to the surprised reader that the era of bloodshed, concentration camps, and hostages had begun immediately after Lenin and his accomplices had usurped the power. In the winter of 1917 <Russian> democrats still believed that the Bolshevist dictatorship could be thwarted].

3. R214/S119/E245

Za iskliucheniem nekotorykh dragotsennostei, sluchaino zakhvachenny i khitroumno

skhoronennykh v zhestiankakh s tualetnym tal’kom, u nas ne ostavalos' nichego. No ne eto bylo, konechno, sushchestvenno. Mestnoe tatarskoe pravitel'stvo smeli noven'kie sovety, iz Sevastopolia pribyli opytnye pulemetchiki i palachi, i my popali v samoe skuchnoe i unizitel'noe polozhenie, v kotorom mogut

[32]

byt’ liudi, — to polozhenie, kogda vokrug use vremia khodit idiotskaia prezhdevremennaia smert', ottogo chto khoziainichaiut chelovekopodobnye, i obizhaiutsia, esli im chto-nibud’ ne po nozdre. Tupaia eta opasnost' plelas' za nami do aprelia 1918-go goda. Na ialtinskom molu, gde Dama s Sobachkoi poteriala kogda-to lornet, bol’shevistskie matrosy priviazyvali tiazhesti k nogam arestovannykh zhitelei i postaviv spinoi k moriu, rasstrelivali ikh; god spustia, vodoloz dokladyval, chto na dne ochutilsia v gustoi tolpe stoiashchikh na vytiazhku mertvetsov.

(Except for a few jewels randomly taken along and astutely buried in the talcum powder containers, we were absolutely ruined. But this was a very minor matter, of course. The local Tatar government had been swept away by a brand-new Soviet, expertly machine-gunners and headsmen arrived from Sebastopol, and we found ourselves in the most preposterous and humiliating situation of all, when idiotic premature death toddles by your side all the time because the ruling humanoids get offended whenever something goes against the grain with them. This dull danger trudged in our footsteps until April of 1918. On the Yalta pier (where the lady with the lapdog once lost her lorgnette) Bolshevik sailors attached weights to the feet of detained citizens and, placing them with their backs to the sea, shot them. A year later, a diver reported that upon reaching the bottom he found himself in a dense crowd of corpses standing at-attention.]

4. R223-4/S122/E262

To nemnogoe, chto moi Bomston i ego druz’ia znali о Rossii, prishlo na zapad iz kommunisticheskikh mutnykh istochnikov. Kogda ia dopytyvalsia u gumanneishego Bomstona,kak zhe on opravdyvaet prezrennyi i merzostnyi terror, ustanovlennyi Leninym, pytki i rasstrely, i vsiakuiu druguiu poloumnuiu pravdu, — Bomston vybival trubku о

[33]

chugun ochaga, menial polozhenie nog i govoril, chto ne bud' soiuznoi blokady, ne bylo by i terrora.

[The little my Bomston <named so after Lord Edward of Rousseau’s Julie. He is Nesbit of the English version of the memoir. GA.B.> and his pals knew about Russia had come to the West through polluted Communist channels. When challenged to justify the despicable and abject terror sanctioned by Lenin — the torture-house, the blood-bespattered wall, and all other kinds of raving truth — the most humane Bomston would tap the ashes out of his pipe against the fender knob of the mantelpiece, recross his huge legs, and say that had there been no "Allied Blockade", there would have been no terror.

5. R224/S122/E262-3

Emu nikogda ne prikhodilo v golovu, chto esli by on i drugie inostrannye idealisty byli russkimi v Rossii, ikh by leninskii rezhim istrebil nemedlenno.

[He never realized that had he and other foreign idealists been Russians in Russia, he and they would have been destroyed by Lenin's regime at once].

6. R224/S122/E263

Osobenno menia razdrazhalo otnoshenie Bomstona k samomu Il'ichu, kotoryi, kak izvestno vsiakomu obrazovannomu russkomu, byl sovershennyi meshchanin v svoem otnoshenii к iskusstvu, znal Pushkina po Chaikovskomu i Belinskomu i "ne odobrial modemistov", pri chem pod "modemistami” ponimal Lunacharskogo i kakikh-to shumnykh ital'iantsev; no dlia Bomstona i ego druzei, stol' tonko sudivshikh о Donne i Khopkinse, stol' khorosho ponimavshikh raznye prelestnye podrobnosti v tol'ko chto poiavivsheisia glave ob iskuse Leopol'da Bluma, nash ubogii Lenin byl chuvstvitel'neishim.

[34]

pronitsatel’neishim znatokom i pobornikom noveishikh techenii v literature, i Bomston tol'ko sniskhoditel'no ulybalsia, kogda ... etc.

[The thing that irritated me most was Bomston's attitude toward Ilyich himself who, as all cultured Russians know, was an accomplished Philistine in aesthetic matters, knew Pushkin by Chaykovski's operas and Belinski's essays, and "disapproved of modernists" - by that meaning Lunacharski and some rowdy Italians. But for Bomston and his friends, who could talk about Donne and Hopkins with such subtle discrimination and could understand so well various delightful intricacies in the recently published chapter on Leopold Bloom's temptation, our paltry Lenin was the most sensitive and perspicacious connoisseur and promoter of the newest trends in literature and Bomston would only smile a superior smile when ...]

7. R225/S123/E264-5

la kstati gorzhus', chto uzhe togda, v moei tumannoi, no nezavisimoi iunosti, razgliadel priznaki togo, chto s takoi strashnoi ochevidnost'iu vyiasnilos' nyne, kogda postepenno obrazovalsia nekii semeinyi krug, sviazyvaiushchii predstavitelei vsekh natsii: zhovial'nykh stroitelei imperii na svoikh prosekakh sredi dzhunglei; nemetskikh mistikov i palachei; materykh pogromshchikov iz slavian; zhilistogo amerikantsa-linchera; i na prodolzhenii togo zhe semeinogo kruga, tekh odinakovykh, mordastykh, dovol'no blednykh i pukhlykh avtomatov s shirokimi kvadratnymi plechami, kotorykh sovetskaia vlast’ proizvodit nyne v takom izobilii posle tridtsati s lishnim let iskusstvennogo podbora.

[Indeed, I pride myself with having discerned even then, in my nebulous but independent youth, the symptoms of what is so dreadfully clear today, when a kind of family circle has gradually been formed, linking representatives of all nations — jolly empire-

[35]

builders in their jungle-clearings, German mystics and hangmen, the good old pogromshchik of Slavic descent, the lean American lyncher, and, on the extension of the same family circle, those identical, square-jowled, rather pastefaced automatons in highshouldered jackets whom the Soviet State produces now on such a scale after more than thirty years of selective breeding.]

8. R232-3/S125/E272

V svoe vremia, v nachale dvadtsatykh godov, Bomston, po nevezhestvu svoemu, prinimal sobstvennyi vostorzhennyi idealizm za nechto romanticheskoe i gumannoe v merzostnom leninskom rezhime. Teper', v ne menee merzostnoe tsarstvovanie Stalina, on opiat' oshibalsia, ibo prinimal kolichestvennoe rasshirenie svoikh znanii za kakuiu-to kachestvennuiu peremenu k khudshemu v evoliutsii sovetskoi vlasti. Grom "chistok", kotoryi udaril v "starykh bol'shevikov", geroev ego iunosti, potrias Bomstona do glubiny dushi, chego v molodosti, vo dni Lenina, ne mogll sdelat's nim nikakie stony iz Solovkov i s Lubianki. S uzhasom i otvrashcheniem on teper’ proiznosil imena Ezhova i Iagody, no sovershenno ne pomnil ikh predshestvennikov, Uritskogo i Dzerzhinskogo. Mezhdu tern kak vremia ispravilo ego vzgliad na tekushchie sovetskie dela, emu ne prikhodilo v golovu peresmotret', i mozhet byt' osudit', vostorzhennye i nevezhestvennye predubezhdeniia ego iunosti: ogliadyvaias' na korotkuiu leninskuiu eru, on vse videl v nei nechto vrode quinquennium Neronis.

Bomston posmotrel na chasy, i ia posmotrel na chasy tozhe, i my rasstalis'.

[Formerly, in the early twenties, Bomston, owing to his ignorance, had mistaken his own ebullient

[36]

idealism for a romantic and humane something in Lenin's ghastly rule. Now, in the days of no less ghastly reign of Stalin, he was wrong again, for he was mistaking a quantitative increase in his own knowledge for a qualitative change to the worse in the evolution of the Soviet regime. The thunderclap of "purges" that had struck at "old Bolsheviks", the heroes of his youth, had given him a profound shock, something that in Lenin's day all the groans coming from the Solovki <forced labor camp on an island in the White Sea> or the Lubyanka <Cheka dungeon in Moscow> had not been able to do. With horror and disgust he pronounced now the names of Ezhov and Yagoda, but quite forgot their predecessors, Uritski and Dzerzhinski. While time had improved his judgment regarding contemporaneous Soviet affairs, he did not bother to reconsider and, perhaps, condemn the admiration and preconceived notions of his youth. Looking back at the short Lenin era, he still saw in it a kind of quinquennium Neronis.

Bomston looked at his watch, and I looked at mine, and we parted.]

9. R246/S129/E289

...v svoe vremia Rossiia izobrela genial'nye etiudy, nyne zhe prilezhno zanimaetsia nagromozhdeniem serykh tem v poriadke udarnogo perevypolneniia bezdarnykh zadanii. <It is amusing to watch the Soviet editors stumble here of all places for the second time: the very first publication of Nabokov in the U.S.S.R., in the chess weekly "64", omitted the whole sentence altogether; now they cannot bring themselves to let stay the last two words of it, thereby lopping off the point of the pun>.

(...in times past Russia invented brilliant end-game studies, but now she has applied herself to the assiduous piling up of dull themes, overfulfilling quotas for brainstorming scatterbrained tasks.).

[37]

If printed, all these passages would have proved beyond the slightest doubt that Nabokov indeed never accepted the "insane reality" (poloumnuiu pravdu) of Sovietdom, heroic as a slaughterhouse and apparently perdurable. But cut as they have been, they prove it even more conclusively.

ABUSIVE EVIDENCE

by Dmitri Nabokov

Drugie berega [Other Shores] has also recently appeared in book form, accompanied, in the same volume, by Mashen'ka [Mary], Zashchita Luzhina [The Defense], and Priglashenie na kazn' [Invitation to a Beheading] (Moscow, Khudozhestvennaya Literatura, 1988). At present I shall briefly address mainly Drugie berega, as a kind of post scriptum to Gene Barabtarlo's meticulous dismemberment of the Druzhba narodov variant.

The unscholarly and offensive introduction to the entire volume, in this case by one Oleg Mikhailov, is hardly worthy of comment, unless it is to point out such ludicrous howlers as, on the first page, "[Nabokov] umer v svoem imenii Montreux" ["(Nabokov) died on his estate (called) Montreux”], and the title Vsglyani na arlektna [Glance at the Harlequin"(sic)] for Look at the Harlequins!. One might also explode the argument that controversial Nabokov cannot be published "v Soyuze" without the counterpoint of a negative introduction. Witness Lidia Libedinskaya's highly complimentary (and very perceptive) sleeve notes for a 1988 two-record set by

[38]

Melodiya (and you can’t get more official than that), Vladimir Nabokov, Drugie berega stikhi i prosa.

The principal "political" cuts correspond more or less to the ones in Druzhba narodov (e.g. pp. 437, 495, 497).

(For Nabokov's English equivalents of the latter two omissions, which are substantial, see Speak, Memory, ch. 12, subchapters 3 and 4.)

Then there are the hilarious inanities, such as translating (footnote to Priglashenie na kazn', p. 320) "en fait de potage" as "prigotovit sup" ["to make soup”) and ascribing the note to the author for good measure; attributing to Nabokov a footnote explanation (Drugie berega, p. 374) that muscae volitantes is a "French" term; or (Compiler's Notes," p. 510) proposing "kabina zada” ["Buttocks' cabin"! for "Zed’s cabin,” a tongue-in-cheek reference by Nabokov in one of his lectures to Doctor Zhivago.

This is only a sampling, and I shall not even bother to list any of the sundry minor warts resulting from insufficient erudition or sloppy proofreading.

I learn now that the same publishing house has commissioned its own translation of Pnin, when an excellent one, done by Barabtarlo and blessed by Véra Nabokov's collaboration, exists and has in fact already been published in a Soviet review. All of this -- the ignorant attitude to art, the utter disregard for the artist, the fear of his superiors' wrath — is more typical of a KGB thug than of a literary editor.

I have repeatedly been invited to visit Russia, both officially and unofficially. I am certain there are individuals there I would like to meet, and forests I would like to smell. But I will not visit a country where one must still delete paragraphs for political reasons, or where glasnost', whatever it is, has caused

[39]

piracy to prevail In the publication of my father's work ever since the flight of the first swallow in 1986.

ABSTRACTS

HISTORY AS FICTION AND FICTION AS HISTORY IN NABOKOVS "THE ASSISTANT PRODUCER"

by Galina De Roeck

(Abstract of a paper delivered at the Annual AATSEEL Convention, Washington, D.C., December, 1988)

This paper is a prologomenon toward the general topic of Nabokov’s fictional relationship to history, using as an initial test case the short story 'The Assistant Producer." "The Assistant Producer" seems to be entirely dependent on the events of a cause célèbre of the 30's, namely the abduction in Paris of General Miller, head of an émigré veterans’ association, the Russian General Military Union. My premise is that once hired as an assistant producer, life or more properly history (since in this case the peripeteia of private lives are displayed on the public stage of history) needs to be paid off in some historically viable currency as well as in the more familiar coin of fictional pleasure. A study of the historical materials which Nabokov uses yields an insight into the poetics of his fiction at the boundaries of history, and the masterful exploitation of those boundaries.

My discussion of some historical sources demonstrates the pitfalls of history as to reliability of fact and sureness of judgment. As an illustration, I

[41]

cite the arguments in the pages the New York Times and the New York Review of Books between the historians Stephen Schwartz and Theodore Draper around the identity of Dr. Eitigon, a peripheral figure in the Miller affair and Nabokov’s story. As may be expected, Nabokov exploits these problems of history by presenting it from the start as more fictional than fiction itself, using film as the ultimate metaphor of authenticated deception. It would appear then that history was invited as an assistant producer to be given enough rope to write itself which it did in displaying its cinemascopic standards of taste in matters of truth. It is time for the man in charge, the producer/narrator, to step in to set the record straight.

His claim on truth is a broader one. If he does not exactly place himself above the facts, he insists on the right to follow his own powers of divination and sympathy should those facts fail. (For the truth writ large across the screen of history is not the only truth, and hence perhaps not truth at all.) The narrator's claim as an eye-witness concerns the hidden recesses of the soul as well as the melodrama of historical appearances. He is obviously an insider, one who perhaps shared the dream of the silent majority of the Russian emigration, those "...working families in remote parts of the Russian diaspora, plying their humble but honest trades, as they would in Saratov or Tver ...mainly believing that the WW (White Warriors) was a kind of King Arthur's Round Table.” That dream, so painfully caricatured in the annals of history, is at least part and parcel of the truth and may not be allowed to be "pruned” as a "mere excrescence upon the main theme.” That the dream deserved, perhaps, to be caricatured at the hands of history is by no means overlooked. In short, the dream of fiction and the nightmare of history are both fertile ground for typically Nabokovian free play and double dealing, where in the interests of truth history outdoes the probability of fiction and fiction naturalizes the improbability of history.

[42]

SCIENCE (AND ) FICTION IN "LANCE"

by Yvonne Howell

(Abstract of a paper delivered at the Annual AATSEEL Convention, Washington, D.C., December, 1988)

Simon Karlinsky has described "Lance” as a short story combining "... three distinct superimposed levels of reality: interplanetary exploration, mountain climbing, and medieval romance." I will argue that there is an additional metaphorical layer of gnostic imagery; that is, a fourth, spiritual "level of reality" not to be overlooked.

On the level of "interplanetary exploration," we are dealing with the characteristic plot structure of science fiction. Nabokov takes advantage of two of the genre’s salient features: 1. The romantic roots of the science fiction genre make it amenable to the depiction of a spiritual quest (Lance, Lancelot, the search for the Holy Grail); 2. Science fiction lends itself well to a spatial depiction of the discontinuity between reality and its representation. The narrator of "Lance” claims to "utterly spurn and reject so-called 'science fiction,'" which is notoriously inept in its pretentions to give the alien, the nonhuman, the Other, a humanly imaginable form. However, the author of "Lance" seems to enjoy the conventions of science fiction as at least one way of naming the inexpressible, giving shape to the unimaginable, in order to grapple with it, to transcend it. Already in the second sentence we are told that the planet Lance is going to "... may well be separated from the earth by only as many miles as there are years between last Friday and the rise of the Himalayas—" This simile contains the compositional and conceptual import of the whole: the interchangeability of time and space not only justifies the characteristic plot structure of science fiction, it is also — in Nabokov’s handling — the underlying theme of the story.

[43]

Emery L[ance] Воkе, the hero of the story, participates in the first manned expedition to a planet in outer space (Mars). His anxious parents imagine his progress and await his hoped-for return in terms of the images and metaphors of the medieval romance — the "out of date" tinge old Mr. Boke gives to this description of interplanetary travel is justified by Nabokov's observation that "out of date" terms are "the only ones in which we are able to imagine and express a strangeness no amount of research can foresee."

Lance's "distant relation," Mr. Nabokov himself, sees Lance’s exploits first in terms of a mountaineering expedition, where the son’s very real, physical confrontation with death provokes both apprehension and admiration from the narrator/parent, "who [is] fifty and terrified." Finally, the spiritual content of Lance's cosmonaut/alpinist exploits exerts a tremendous pull on the language and imagery used to describe the climb, as the Bokes presumably watch Lance through their telescope: "...crossing a notch between two stars...[then] dreadfully safe, on a peak above peaks, his eager profile rimmed with light." The "notch between two stars" suggests the celestial charts of the Neo-Platonists. Ascendance through the successive astral and planetary spheres is equivalent to unburdening oneself of layer upon layer of evil (matter), and approaching the state of a pure, divine, acosmic spirit. Thus, Lance's interplanetary trek turns into another metaphor for the gnostic journey through matter and evil back up to divine light. Lance can remain of a body, and the conventions of science fiction allow him to travel, bodily whole, through the concentric spheres of being.

Viewed in this way, the story "Lance" offers a rare, but fine refutation to the commonly-held notion that "science fiction" is inherently trashier than "surrealism," or, in other words, that projecting Time outward into cosmic space necessarily results in aesthetically clumsier monsters than those produced

[44]

when Time is projected inward, as psychological space.

University of Michigan

"MASTERY, TRANSCENDENCE, AND THE 'HEGELIAN SYLLOGISM OF HUMOR’ IN PALE FIRE'

by James F. English

(Abstract of paper delivered at the Annual MLA Convention, New Orleans, December, 1988)

As a modernist writer, Nabokov saw the aesthetic not as an end in itself but as a means of transcending prevailing social conditions in the direction of what Jurgen Habermas has called a "'happier' communicative experience,'' an "experience of solidary living with others." Nabokov's participation in this modernist project of "art for life's sake" can be clearly observed in the humor of his texts. The special "Hegelian" movement of his humor, a quasi-dialectical movement of subjects and objects, jokers and targets, is meant ultimately to defeat the social categories of "insider” and "outsider" on which that humor depends, and thereby to open the way for ideally "happy" communication, for tolerant and non-coercive sociality. But, as the example of Pale Fire demonstrates, a joke's syllogistic movement cannot be controlled by the author/humorist from a stable position of mastery. Whatever the author's "serious" intentions, the joke-work performed by Pale Fire remains as hegemonic as it is emancipatory; like other modernist texts Pale Fire reinforces old lines of exclusion and hierarchy even while it struggles to secure the communicative conditions of a better society.

University of Pennsylvania

[45]

"NABOKOV WOULD BE HORRIFIED": AUTHORIAL POSITION IN NABOKOVIAN CRITICISM

by Brenda K. Marshall

(Abstract of a paper delivered at the Annual MLA Convention, New Orleans, December 1988)

Many of us, as Nabokov critics, accede authority to Nabokov in our determination of what constitutes appropriate criticism. It is rare indeed to find an article on Nabokov that doesn't at some point use an opinion of his as a support for the argument being made. I am calling for an increased awareness of how our criticism fits within, and is determined by, what I call a "Nabokovian matrix." For example, each of us knows of Nabokov’s emphasis on how something is said over what is said. So when we direct our criticism toward statements that Nabokov's works are about art and the artist, we remain comfortably within a framework authorized by Nabokov. But we also know that there are terms of import besides the how and the what, notably, the why. I am not speaking of authorial intention, but rather, of critical intention: what are the underlying assumptions that we need to acknowledge when we, for example, write articles that assume an absolute and accepted definition for morality, or when we write articles that assume that the centers for Nabokov's novels are consistently the "male genius." My point is that there is a real and controlling relation between how we do our criticism and Nabokov's opinions, that our criticism often uncritically replicates and reinforces a patrilineal pattern.

Edward Said's discussion of the concepts of filiation and affiliation in The World, the Text, and the Critic provides useful terms by which to discuss this patrilineal pattern. Filiation is the concept of natural, biological descent, a progression ensured by

[46]

natural bonds and authority (obedience, fear, love, respect). Said posits that filiation has been replaced by the compensating order of affiliation, that is, through ties that link through cultural constructs: institutions, associations, and communities. What is significant for our purposes is "the deliberately explicit goal of using that new [affiliative] order to reinstate vestiges of the kind of authority associated in the past with the filiative order" (Said, p. 19). As Nabokovian critics we base our own importance, not on vertical descent from Nabokov, but on our horizontal affiliation with Nabokov's role in the genealogy of great literature. Within our compensatory order of affiliation, the Nabokov community of scholars often replicates the underlying assumptions of filiation itself. Either way, the dead father lumbers along.

My concern is with the normalizing potential for any "authoritative" affiliative community. We need to be aware of and acknowledge our own interpretive positions; we must function as critics who recognize our own social, political, cultural positions and agendas which create our own strong opinions. Although our affiliation may replace the authority of the filiative structure, it is up to us to use our affiliative authority not to replicate paternalistic filiation, but, rather, to challenge it.

University of Massachusetts-Amherst

[47]

"THE GIFT AND RELATED WORKS"

by Charles Nicol

(Abstract of a paper delivered at the AAASS meeting in Boston, November 1987)

My general contention is that The Gift occupied Nabokov's imagination more fully than any other work during his Russian period, and that other works written as interruptions to his creation of that novel are frequently related to it. In considering the works written during its composition which Nabokov himself In one way or another cross-referenced to it, I find substantial evidence pointing to 1934 as the major year of his creative and combinational activity on The Gift. This brings into question Nabokov's statements that 1935-1937 were the major years of his work on his greatest Russian novel.

The most obviously related work, "The Circle," was published early in 1934 (not in 1936 as Nabokov stated). In my reading, this story is related to The Gift’s second chapter (not its fourth as Nabokov stated), and the actual dating of the story's publication leads to a suggested correction in one passage of its English translation. A detailed revision of this section of the essay appears in the Annotations & Queries section of this issue of the Nabokovian.

A second item is the poem, originally untitled with the heading "Iz F. F. Ch." and later titled "L’Inconnue de la Seine," which appeared in late June 1934. While the ostensible author is clearly the writer-protagonist of The Gift, the only conclusion I could reach was the tentative suggestion that the poem was in some way a joke on, or criticism of, "the anemic 'Paris school' of émigré poetry." The fact that nine months later.

[48]

"Torpid Smoke" makes another reference to L'Inconnue de la Seine, this time as, apparently, a popular print, leads to a discussion of the drowned-woman theme in European art in the late nineteenth century, and to a poem by Nekrasov discussed in the fourth chapter of The Gift. (Many of the puzzling aspects of this reference have since been cleared up by D. Barton Johnson in an as yet unpublished essay.)

A substantial section on Invitation to a Beheading finds its origins in Nabokov's Chernyshevsky research and compares it to similar and counter impulses in Russian science fiction, including Zamyatin's We, that find their origin in Chernyshevsky. I suggest that Invitation may well have been written while Nabokov was struggling with Chapter Four of The Gift (the Chernyshevsky biography). I hope to expand on these observations at a later date, once Invitation’s birth date is confirmed.

A less important relationship of "Recruiting" (August 1935) to the last chapter of The Gift is also discussed, based on the similarity of situations (an imaginary conversation on a park bench) and the statement in the story that "I had to have somebody like him for an episode in a novel with which I have been struggling for more than two years." I suggest that the narrator, whether Fyodor or Nabokov, is referring to The Gift, and that this reference is more accurate than later reminiscences in suggesting that Nabokov had been working on The Gift since the middle of 1933.

A final section speculates on why, if the novel was indeed close to completion by late 1935, it only began to appear in early 1937. Inasmuch as I anticipate that Brian Boyd's biography will soon confirm or outdate these speculations, I have no plans to publish this tentative dating of the composition of The Gift in greater detail.

Indiana State University