Download PDF of Number 24 (Spring 1990) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 24 Spring 1990

______________________________________

CONTENTS

From the Editor 3

News by Stephen Jan Parker 4

The Gettysburg Address translation

by Vladimir Nabokov 8

Nabokov's Chernyshevski in the Contemporary Annals

by Gennady Barabtarlo 15

Annotations & Queries by Charles Nicol

Contributors: Gennady Barabtarlo, Alexander Lehrman,

William Rasch, Pekka Tammi, Gerard de Vries 24

Untitled Poem, 7 December 1923 by Vladimir Nabokov

Translation by Dmitri Nabokov 46

Abstract: Khani Begum, "Sex and Gender in

Nabokov's Lolita: A Post Lacanian Feminist Dialectic" 50

V.V. Nabokov in the USSR: 1976-1981

by N. Artemenko-Tolstaia and E. Shikhovtsev 52

[3]

From the Editor

In May 1940, Vladimir Nabokov arrived in the USA, at last free of political oppression. Five years later he became an American citizen, and then proudly maintained that citizenship the rest of his life. In 1966, "with intense pleasure," he accepted an offer from The Library of Congress to translate into Russian Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. To commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of VN's emigration to America, with the assistance of the Nabokov archives, we are publishing VN's translation of Lincoln's address along with the associated documentation.

*****

Subscriptions have decreased nearly 18% in the past year, while costs continue to escalate. The number of submissions of news items, abstracts, and other pieces for publication is the lowest it has been in ten years. Has The Nabokovian outlived its usefulness

Our financial situation has always been precarious, and it is only through the generosity of several loyal subscribers that we have been able to continue publication this long. Logic suggests that this is not the time to announce an increase in rates, but reality makes it imperative. Thus, beginning with 1991 subscriptions, rates will be as follows (postage rates reflect announced federal rate increases):

[4]

Individuals: $ 9 per year

Institutions: $11 per year

surface postage outside the USA: $3.00

airmail postage to Europe: $7.00

airmail postage to Australia, New Zealand, India, Israel, Japan: $9.00

Back issues:

Individuals: $5.50 each

Institutions: $7.00 each

airmail postage to Europe: $3.50

airmail postage elsewhere: $4.50

I hope the new rates will not result in a further loss of subscriptions, and that readers will renew their commitment to The Nabokovian by submitting items for publication.

SJP

NEWS

From Galya Diment: "The Nabokov Society session at AATSEEL (December 28, 1989) was both well attended and well received. The panel, entitled "Nabokov as Critic" and chaired by Galya Diment, featured full papers by Galina Litvinov De Roeck, "Nabokov and Sartre: Critical Polemics, Literary Symbiosis" and Christine Rydel, "The Fictional Criticism of Vladimir Nabokov," and Anna Ljunggren’s informal discussion on "Nabokov as the Last Russian Dandy." Leona Toker served as the panel's discussant. While discussing organizational matters at the end of the session, it was decided that

[5]

starting with next year, sessions of the Nabokov Society at AATSEEL will no longer limit its panels to special topics. The 1990 AATSEEL session, entitled "Vladimir Nabokov Society," will take place in Chicago and will be chaired by Galina Litvinov De Roeck (Dept, of Russian, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824)."

The MLA sessions were equally well attended (approximately 40 persons) and well received. The first session, "Sexuality in Nabokov’s Narrative" was chaired by Stephen Parker, in the absence of Brenda Marshall, the announced chair. Papers presented were: "Brotherly Love: Nabokov's Homosexual Double," Susan Elizabeth Sweeney; "Love in the Hall of Mirrors: Sexuality and Sameness in Lolita and Pale Fire," Scott Long; and, "Sex and Gender in Nabokov’s Lolita," Khani Begum. The second session, "Approaches to Teaching Nabokov," was chaired by Zoran Kuzmanovich. Papers presented were: '"That Strange, Future, Retrospective Thrill': Canonizing Nabokov," Zoran Kuzmanovich; "Other Voices, Other Classrooms: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Nabokov," Ralph Ciancio; "Nabokov versus the Minimalists: Rediscovering Ornate Style," Thomas Bontly; and, "Consuming Passions: Kubrick's Lolita and the Discourse of Teen Consumerism," Ellen Berry.

This year's MLA and AATSEEL meetings will be held in Chicago. Along with the Society’s session at AATSEEL announced above, one MLA session will be: "Vladimir Nabokov as Stylist" (commemorating the 50th anniversary of Nabokov's emigration to America). Papers and proposals focusing upon the author’s English language style should be sent to Dr.

[6]

Samuel Schuman (Dean's Office, Guilford College, Greensboro, NC 27410).

*

In the Spring 1989 issue it was mistakenly reported that all American rights to Nabokov's English language works are now held by Vintage books. Actually, New Directions and Bruccoli Clark also hold rights to several titles.

*

A recent publication: Der Tod im Werk Vladimir Nabokovs "terra incognita". Christopher Hüllen. Munich: Verlag Otto Sagner in Kommission, Arbeiten und Texte zur Slavistik 48, 1990, 254 pages. Dr. Нüllеп (Bonner Ring 151, 5042 Erftstadt, West Germany) writes: "It is the first dissertation on Nabokov written in the Slavic Department of a German University. It is also the first German book on Nabokov which deals with both his Russian and English works. It contains a chapter on the history of Nabokov criticism inside and outside the emigre community and in the Soviet Union. The second chapter contains an analysis of Nabokov's philosophy with special reference to the problem of death. Chapters 3 and 4 deal with the depiction of death in Nabokov's works and with the concept and understanding of death that can be deduced from this depiction."

*

From Gene Barabtarlo: In their thorough list of Soviet notices of Nabokov’s name (The Nabokovian

[7]

#23), the compilers put to question items 15 and 19 (p.44), which I mention in my note published in No. 13 (1984, p.28-31). Yet I saw — though unfortunately did not take down — both citations in 1977, in the card catalogue (under Nabokov: a meagre batch then) of the Moscow Foreign Language Library. Even if that third article by the late Mme. Orlov should turn out to be a ghost progeny of the other two I had found there (items 13 and 18 in the Artemenko-Shikhovtsev Bibliography) — in my note I say that I am "reasonably sure" it exists, but could have erred, — I remember with perfect clarity the card with the title of the other item ("Golos s drugogo berega"), and the brief annotation. The date was between 1957 and 1959, the place, the Sovetskala Rossia daily -- or so I thought: but since the compilers could not find it there, it must have been some other newspaper (Literaturnaia Gazeta? Sel'skaia Zhizn'?). My hoaxes are limited to the special semi-sportive anniversary issue 20 (1988).

*

Many thanks to Ms. Holly Stephens and Ms. Paula Malone for their invaluable aid in the preparation of this issue.

[8]

Vladimir Nabokov’s Translation of The Gettysburg Address

To: Vladimir Nabokov

Reference Department

Office of the Director

The Library of Congress

Washington 25, D.C.

April 5, 1966

Dear Mr. Nabokov:

The Library of Congress would like to publish a small brochure of Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address translated into all the principal languages of the world.

We have been unable to find a really good Russian translation, and wish to solicit your aid. Would you consider making such a translation for the Library to publish, together with the best translations we are able to obtain in other languages? The brochure would be distributed principally to foreign visitors to the nation's capital, but perhaps also abroad by way of the information service.

I hope you will consider this seriously as a public service, since I can offer only a very modest honorarium of one hundred dollars for the work.

[9]

I shall hope to hear from you.

Sincerely,

Roy P. Basler Director

To: Roy P. Basler, Esq.

Montreux, April 9, 1966

Palace Hotel

Dear Mr. Basler,

With intense pleasure I accept your offer that I translate the Gettysburg Address, a work of art I have always admired. The translator's task is not made easy by the play on "dedicate" and other stylistic features of the speech but I think I can turn it into reasonable Russian. You will get it in a day or two.

I have two small requests: My name as translator must be mentioned, and no alterations can be made without my approval. I must also be allowed to correct the proof.

[10]

As to the honorarium, please transmit it to some worthy charity.

Sincerely yours,

Vladimir Nabokov

To: Roy P. Basler, Esq.

Montreux, April 12, 1966

Palace Hotel

Dear Mr. Basler,

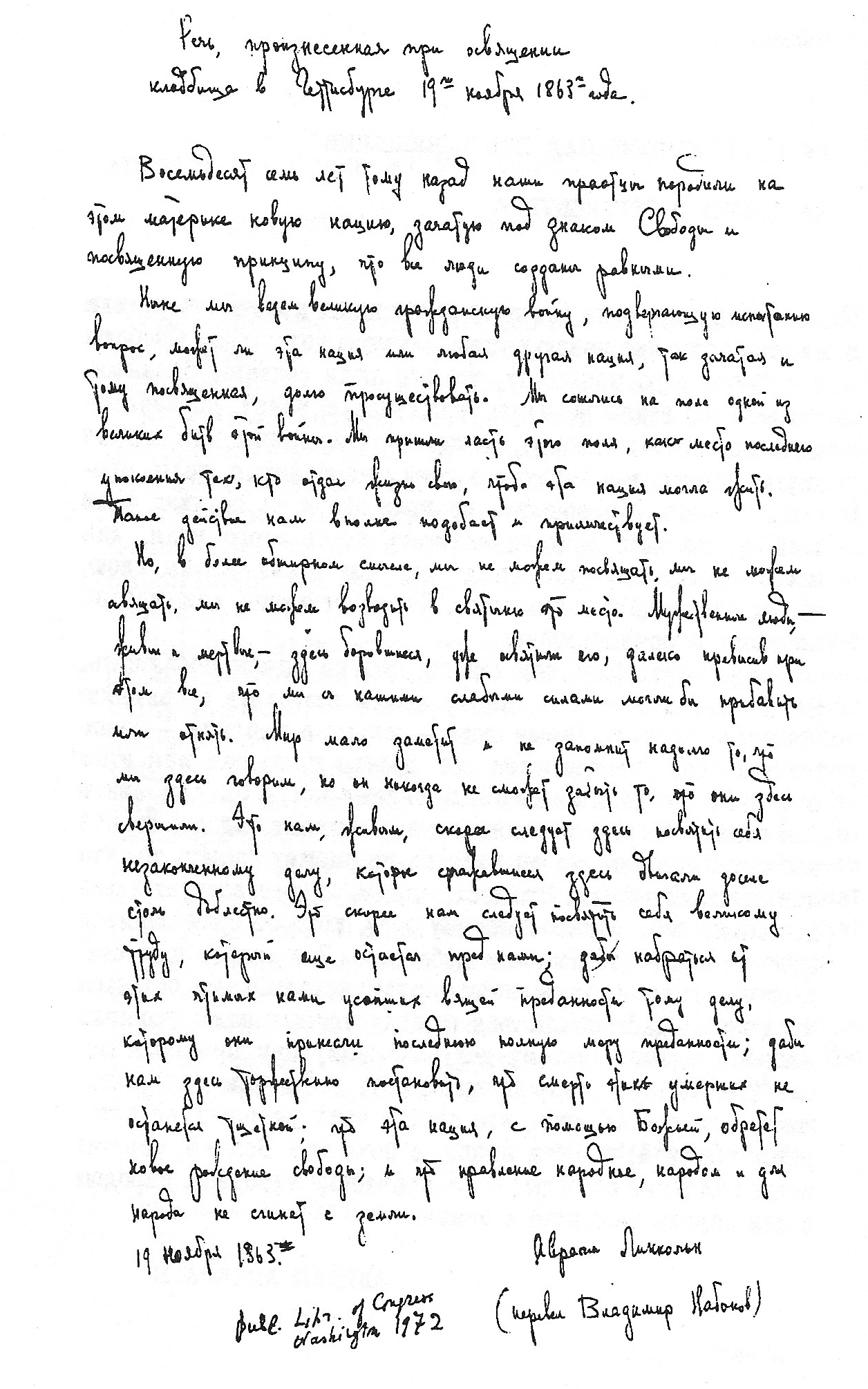

Please find enclosed my translation into Russian of The Gettysburg Address.

Sincerely yours.

Vladimir Nabokov

P.S. Incidentally, not having a Russian typewriter here, I wrote the translation in long hand. This manuscript may be added to the Library's "Nabokov collection."

Copyright © 1989 Vladimir Nabokov Estate

[11]

[12]

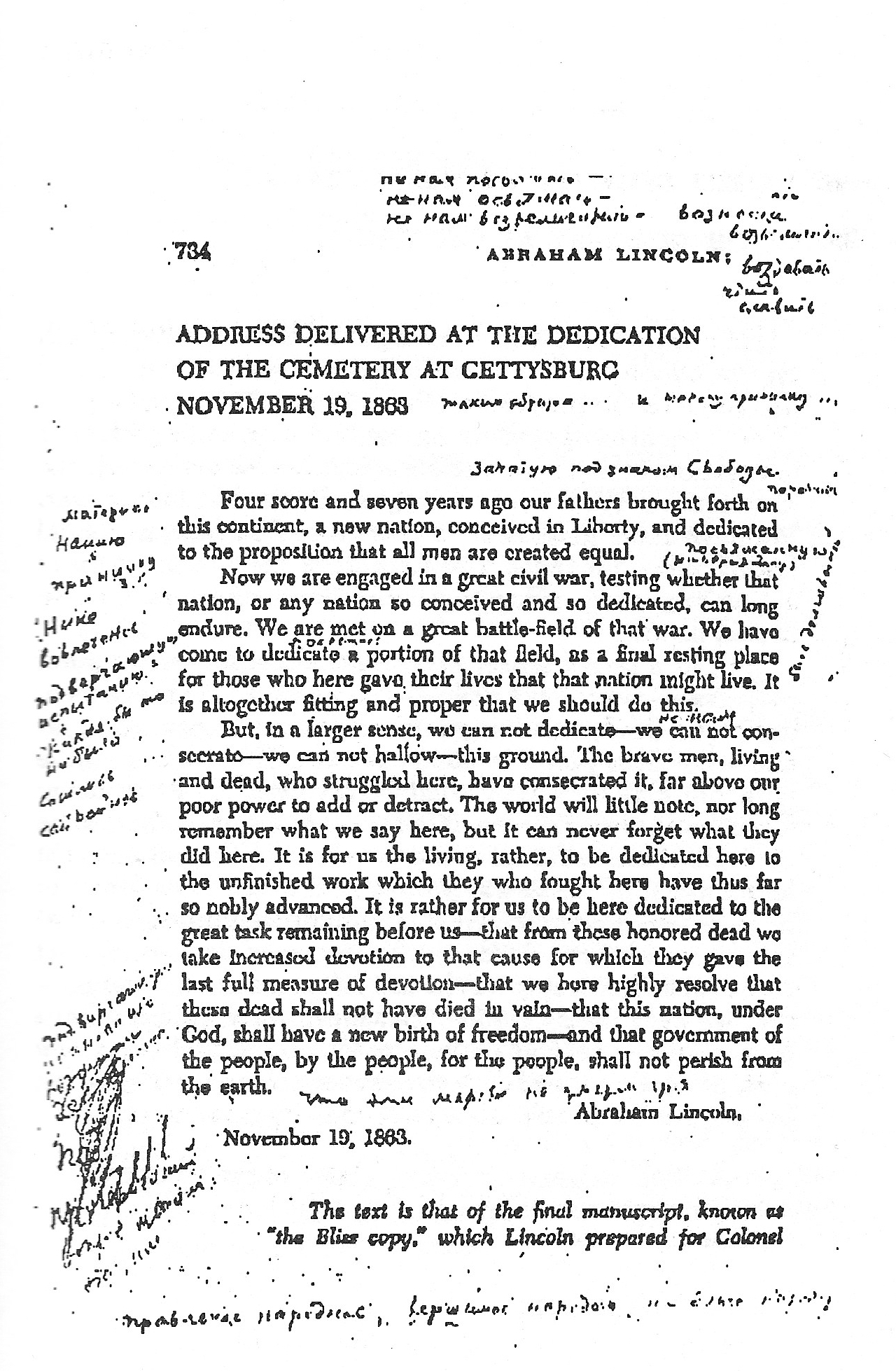

ENGLISH

ADDRESS DELIVERED AT THE DEDICATION OF THE CEMETERY AT GETTYSBURG

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion— that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

November 19, 1863.

[13]

RUSSIAN

РЕЧЬ, ПРОИЗНЕСЕННАЯ ПРИ ОСВЯЩЕНИИ КЛАДБИЩА В ГЕГГИСБУРГЕ

Восемьдесят семь лет тому назад наши праотцы породили на этом материке новую нацию, зачатую под знаком Свободы и посвященную принципу, что все люди созданы равными.

Ныне мы ведем великую гражданскую войну, подвергающую испытанию вопрос, может-ли эта нация или любая другая нация, так зачатая и тому посвященная, долго просуществовать. Мы сошлись на поле одной из великих битв этой войны. Мы пришли освятить часть этого поля, как место последнего упокоения тех, кто отдал жизнь свою, чтобы эта нация могла жить. Такое действие нам вполне подобает и приличествует.

Но, в более обширном смысле, мы не можем посвящать, мы не можем освящать, мы ие можем возводить в святыню это место. Мужественные люди,—живые и мертвые,—здесь боровшиеся, уже освятили его, далеко превысив при этом все, что мы с нашими слабыми силами могли бы прибавить или отнятъ. Мир мало заметит и не запомнит надолго то, что мы здесь говорим, но он никогда не сможет забыть то, что они здесь свершили. Это нам, живым, скорее следует здесь посвятить себя незаконченному делу, которое сражавшиеся здесь двигали доселе столь доблестно. Это скорее нам следует посвятить себя великому труду, который еще остается пред нами; дабы набраться от этих чтимых вами усопших вящей преданности тому делу, которому они принесли последнюю полную меру преданности; дабы нам здесь торжественно постановить, что смерть этих умерших не останется тщетной; что эта нация, с помощью Божьей, обретет новое рождение свободы; и что правление народное, народом н для народа не сгинет с земли.

АВРААМ ЛИНКОЛЬН.

19 ноября 1863.

Перевел Владимир Набоков

[14]

[15]

NABOKOV'S CHERNYSHEVSKI IN THE CONTEMPORARY ANNALS

by Gennady Barabtarlo

The four Nabokov's letters to Vadim Rudnev (1879-1940), publisher of the Contemporary Annals, and one to Ilia Fondaminski-Bunakov, printed here, shed light on one of the most arrant cases of censorship in Russian emigre literature — the story of the omission of Chapter Four, "The Life of Chernyshevski", from The Gift serialized in the magazine founded and edited by five prominent members of the former Russian Socialist-Revolutionary party. It was a curious instance of Fate's choosing for once not to upset her designs merely to thwart their prefigurement by their victim (in the novel's Chapter Three). The pith of this sad anecdote is well-known; the details are not. The letters below show well how Nabokov’s initially buoyant, if slightly assumed, surety that the chapter will be published in or out of sequence turns first to hopeful disbelief that it may not and then to bitter disappointment when he has realized that for reasons of camphor-ball ideology "The Life of Chernyshevski" will not be placed in the Contemporary Annals and indeed anywhere else.

All four letters first appeared in Russian in the almanac The Bygone (Minuvshee, Paris: Atheneum), No. 8, 1989, pp. 274-81, with a Foreword and commentaries by Mr. Vladimir Alloy. My English

[16]

translation is here published with the permission of Mr. Dmitri Nabokov who kindly agreed to read it in manuscript. My brief notes are in square brackets.

Copyright © The Vladimir Nabokov Estate.

To Rudnev.

1.

27 December, 1934

Dear Vadim Viktorovich,

Very soon you should receive at last the manuscript [of Invitation to a Beheading]; I am only now completing the correction and revision. Anna Lazarevna [Miss Feigin, Vera Nabokov's cousin] advised you of my financial situation. Thank you for offering an advance, it would be most welcome. Anna Lazarevna told me that some short piece of mine could be published in the next issue of C[ontemporary] A[nnals]; in talking with you she mentioned an excerpt from Chernyshevski. I, too, had been considering plucking a chunk out of it but upon examining what I had written I concluded that for the time being one could cull nothing either from Chernyshevski or from the novel of which it will be a component, without damaging the whole. One day soon I shall write a little story. I am afraid that it will be too late for the next issue but do let me know the deadline, just in case.

[17]

Thank you very much for the news concerning Amalia Osipovna [Mme. Fondaminski, née Gavronski, who died in 1935 of consumption); I shall always be grateful if you keep me apprised [of her health) in the future as well.

I wish you a pleasant holiday and shake your hand.

2.

11 February, 1935

Dear Vadim Viktorovich,

It was with a heavy heart that I read what you wrote about Amalia Osipovna’s health. Who is treating her now? What does that new doctor say? Is the situation really that grave?

As for Invitation to a Beheading, I accept all your suggestions. Of course, I cannot agree to any excisions.

I have been working on the novel "about Chernyshevski" for two years now but it is far from being ready for print, to say nothing of the fact that the range of readers able to comprehend it will be perhaps even more limited.

I shake your hand.

[18]

3.

6 August, 1937

Dear Vadim Viktorovich,

Just as I thought, the substitution of one chapter for another alarmed you at first blush. I do not doubt, however, that you are over the initial apprehension now that you have read the chapter, and that you have changed your opinion: after all, this is not a random chapter from the middle of the book, with a plot development yet unknown to the reader, but a completely separate piece of independent value. (My hero and I have worked at it for four years). This is precisely what I meant when I wrote that I considered placing "The Life of Chernyshevski" to be both valuable and profitable for the magazine. On the other hand, I can understand why you are reluctant to print the chapters in the sequence 1-4-2-3-5. Therefore, here is my proposition: 1. Either do not put any chapter number at all and make no mention of The Gift but rather entitle the thing simply The Life of Chernyshevski, or 2. Print it under the title The Gift but head it with "Chapter Two" (instead of "Four").

As regards the second chapter: while working on it most rigorously here, I have come to the conclusion that its entire opening is in need of revamping, which should take me many more weeks of assiduous composition.

Sorry that I should have unwittingly upset you but

[19]

what I propose seems to be a perfectly happy solution.

Cordial greetings.

4.

10 August, 1937

Dear Vadim Viktorovich.

I have read your letter carefully and — forgive my well-meant frankness — it made a distressing impression on me. By refusing to publish Chapter Four of The Gift for reasons of censorship you in effect deny me the possibility of placing the novel in your magazine at all. Bear with me and consider: how can I give you Chapters Two and Three (it is in the latter that the images and opinions which then evolve in Chapter Four and which you reject, already take shape) and then the concluding chapter (where, by the way, I give in toto four reviews of The Life of Chernyshevski chastising the author variously for defiling the memory of that "Great Man of the '60s'" and explaining why this memory is sacred), when I know beforehand that there will be a hole in The Gift, namely a gap in place of Chapter Four (not to mention the related expunctions in other chapters), for I must say unequivocally that I cannot accept any compromise or a joint effort and shall neither take out nor change a single line. Your rejection of my novel is all the more distressing because of the special regard in which I have always held the Contemporary Annals. The fact that it has occasionally run fiction and articles espousing views which the editors obviously could not share has been a unique phenomenon in the history of

[20]

our journalism and has represented a freedom of thought (provided that thought Is expressed with talent and integrity -- almost a tautology, perhaps) has served as a most striking condemnation of the current situation of the press In Russia. Why then do you now tell me of the "public attitude" ("obshchestvennoe otnoshenie", a Russian cultural formula which defies exact rendition since "obshchestvennost’" <not "obshchestvo">, implying as it does more than the merely cultivated public, suggests rather a complex notion of the "intelligentsia"] to my thing? With your leave, my dear Vadim Viktorovich, the public attitude to a literary work is but a consequence of its artistic affect; by no means is it an apriori assessment of that work, I have no intention of defending my "Chernyshevski": in my ultimate judgment, this book is on a plane where no defense is necessary. Suffice it to say, for your colleagues' information, that I do not slight Chernyshevski the freedom-fighter — and not because I did it this way consciously (as you know, I do not care one whit about any political party on earth) but probably because there was more truth in one camp and more evil in the other. And if Vishniak [M. V. Vishniak, one of the Contemporary Annals' editors, 1883-1977] and Avksentiev [N. D. Avksentiev, 1878-1943, another founder of the magazine and, as were the other four, a prominent S-R] had respected Chernyshevski not merely as a revolutionary but as a thinker and a critic (which is the chief theme of my piece), then my research could not have failed but to make them change their minds. In conclusion, allow me to draw your attention to the curious situation I find myself in: I can place "Chernyshevki" neither in [pro-] Soviet publications, nor in any of the "right-wing" organs, nor in the Latest News [Paris Russian émigré daily] (Miliukov [the paper's publisher, 1859-

[21]

1943], to whom I had offered the fragment. Is said to have been offended by a backhand reference to the London Exhibition of 1859), nor in your magazine, as it turns out. You are asking me to help you find a solution for the Contemporary Annals; well, I dare submit to you that my situation is far more insoluble.

Please do not interpret this letter as a burst of authorial arrogance. I write my novels for myself and print them for money — the rest is but the folly of fortuitous fate, tasty tidbits, spring peas to go with my chickens. But it Is sad that you should close for me the only magazine that I find suitable and of which I am very fond.

Cordial greetings.

To Ilia Fondaminski.

16 August, 1937

Dear Ilia Isidorovich.

You are probably aware of my correspondence with Rudnev regarding Chernyshevski. Today I received his letter which left me no choice but to reply as I did: I enclose a copy of my letter to him. I can't tell you how distressing I find the decision of Contemporary Annals to censor my art by applying old partisan prejudices.

Kindly let me know, by return post if possible, whether you intend to keep your promise to print

[22]

"Chernyshevski'' in the Russian Annals, if it comes to that. [Fondaminski edited this newly founded magazine in 19371. If so. could you then possibly publish it in the very next issue (in place of the short story ["Cloud, Castle, Lake”, in No. 2, 1937])? Of course, the thing can be published only in its entirety.

I take this occasion to thank you for sending me the magazine [i.e. the first issue of the Russian Annals.] in which I liked especially Osorgin’s article [Mikhail Osorgin’s <M. A. Iliin, 1878-1943> 'The Court-Sanctioned Murder", against capital punishment] whose theses and pathos I share completely. The splendid article by Davydov [K. N. Davydov, a distinguished zoologist; his essay was entitled "The Migration of Birds"] is unfortunately diluted by needless "popularized" prattle. 'Tolstoy's Liberation" [a long essay on Leo Tolstoy by Ivan Bunin] seems to have liberated Bunin from the exigencies of his own creative writing. Vladimir Mikhailovich’s article [Zenzinov, 1880-1953; 'Youth Goes to the Arctic"] is very interesting; however, what I said was not "primitive" but "lubok" [cheap pop-pap] — a hell of a difference.*

I am also very much concerned about Invitation to a Beheading. [The novel was to appear in book form under the label of Dom Knigi, a firm associated with Fondaminski's publishing enterprise].

I embrace you and Vladimir Mikhailovich.

* [End-note:] Here is what Mr. Alloy says regarding Zenzinov's article: "[It] begins with an account of the Soviet film The Brave Seven which ran in a Paris cinema. After the show, 'a Russian writer, an

[23]

inveterate enemy of the Bolsheviks [Nabokov], exclaimed: A sort of primitive of all human virtues.' Zenzinov’s article is in effect an attempt to gainsay this pronouncement. The . author wistfully begins: 'One leaves the theatre charged with vigor, musing: if only there were more of such young men in today's Russia!' — and proceeds to describe, in the space of twenty-five rapturous pages, the Soviet achievements in Igarka, Magadan, Nogaevo, on the gold mines of Kolyma [the polar regions where the worst extermination labor camps were located, whose inmates worked on the construction sites and in the quarries mentioned in Zenzinov's article. G. B-o.] and to hold forth about the construction of factories and mine-shafts, hospitals and schools, about the cultural blossoming of the Northern tribes, and so on. 'Indeed, Zenzinov writes, they are creating there a new breed of people, people with insuperable energy, fearless people with iron-strong devotion to the cause which they have turned into the main cause of their life.' All this was written about Kolyma in the summer of 1937," reminds Mr. Alloy in conclusion.

[24]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

[Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov's works will be to the most recent hardcover U.S. editions.]

SEE UNDER SEBASTIAN

I admit that the night has been ciphered right well.

but in place of the stars I put letters.

"Fame" (1942)

Something in the name of Sebastian Knight has often made me pause and wonder. He chose his English mother’s maiden name for his nom de plume but he was christened Sevastian, a name regular enough among Russian commoners but extremely rare in the set into which he was born — and I say "rare" simply because I do not wish to expose my vanity to a sneer by saying that it never occurred, although I cannot think of a single Sevastian among the sort of gentry SK's father came from. There is no mention anywhere of Virginia Knight’s insisting on that name for her son. Why Sebastian of all names? Surely Nabokov could have selected one equally natural in its respective

[25]

form to both English and Russian (Andrew Knight, Stephen Knight, Victor Knight). There seems to be something deliberate about Sebastian, at least on the Russian side of it, and I think I now know what it is.

Students of RLSK have often noted that the tempo of the thematic pursuit of the hero receding to the edge of the book, slow and thoroughgoing at the onset, gains much speed toward the end, and finally changes to a breathless rush, chugging along frenetically as the slow, and wrong, train takes V. to the dying Knight over maddening obstacles (the more urgent the hurry the more obstacles V. encounters) and then stops abruptly, in a sudden hush, at the book's terminal where, athwart all expectations, there is no Sebastian Knight waiting. He is "gone . . . the room is empty" (the words of the policeman from Knight's Prismatic Bezel). One is reminded of such important lines as "But there was no Charlotte in the living-room," which is Lolita’s waterline (99) or, more to the point, "But there was no Aleksandr Ivanovich," the bottom line of The Defense. RLSK's final, oft-quoted paragraph contains an elusive confirmation: "Thus — I am Sebastian . . . They move round Sebastian — round me who am acting Sebastian, — and the old conjuror waits in the wings with his hidden rabbit .... The end, the end. They all go back to their everyday life . . . but the hero remains, for, try as I may, I cannot get out of my part . . . I am Sebastian, or Sebastian is I, or perhaps we both are someone whom neither of us knows." Words admitting of all manner of explication, no doubt. But whatever they mean, one thing is certain: there is no Sebastian Knight at the end of the chase, and the reader is made to feel as one who, after carefully inching one's hand into the folds of the net in the hope of finding and nipping a long-hunted rare insect, at

[26]

last triumphantly grabs one's own left thumb—and wakes up.

One of the possible interpretations of the novel's meaning and workings may be that, as the wrappings around Sebastian's "real life" are being unwound, his essence becomes more vaporous, and he wanes to naught when the last layer is removed. This method is akin to one described in Knight's first novel, The Prismatic Bezel (and nutshells of Knight’s novels are all the reader's chief navigation instruments), where at first everyone is suspected of murder, then, gradually, none, then it suddenly becomes clear that no murder has been committed, and the corpse whose looming presence was taken for granted at the beginning turns out to be the chief suspect in disguise. The knot is untied, "the gradual melting process" (in V.'s words, 93) complete, the novel done.

I think that Nabokov encoded this process in the slightly uneasy name of Sebastian which carries the code on its bosom, as it were. "Sebastian Knight" can be rearranged to yield "Knight is absent" with only the indefinite article left on the emptied rack.

The possibility of Nabokov's hiding the key to the book's contrivance by working it into the hero's name and putting it at the entrance (title), or rather under its door-mat, is quite fathomable. He fashioned anagrams carrying secret messages for at least one of his Russian novels and for almost every English one that followed his first. RLSK marked the first stage of the painful tongue-transplant operation, one result of which was the sharply increased frequency and intricacy of verbal acrobatics, tricks at which a prosthesis may be defter than a natural organ. RLSK

[27]

was meant for a London literary competition, and this fact might have particularly moved Nabokov to leave a private watermark visible only through special glasses. The novel was his experimental field where he purposely tried, for the first time in his English prose, various paronomastic games: the corpse of Mr. G. Abeson reversed to good old Mr. Nosebag (the suspect), which obverted to Abeson: and the name of Jeanne D'Arc’s native village (Domremy), which V. erroneously presumes to be written in the same Russian cursive as the rest of Sebastian's letter and thus fails to decipher in meaning or allusion (186; discovered by Mme. Hélène Sikorski). V. receives this letter on a Thursday "in the middle of January" (187, 185), which in 1936 was the 16th, and that night sees a queer dream and in it Sebastian; at the end of the dream Sebastian vanishes but calls out his half-brother to tell him an important truth, "and a phrase which made no sense when I brought it out of my dream, then, in the dream itself, rang out laden with such absolute moment, with such an unfailing intent to solve for me a monstrous riddle, that I would have run to Sebastian after all, had I not been half out of my dream already .... the nonsensical sentence which sang in my head as I awoke was really the garbled translation of a striking disclosure" (190). The word absent appears ten lines below ("it was doubtful whether I could absent myself at all for the weekend"; Knight could, and did).

On Friday the 17th V. receives a telegram from Dr. Starov in which the good doctor spells Knight’s name the Russian way, with the v, and this fact is immediately thrown up. Knight expires in St. Damier that night as V. rides past St. Damier to Paris; then V. returns late on Saturday, spends the night near a

[28]

perfect stranger assumed to be Knight (their names share consonants), makes his ultimate discovery, and the novel ends on Sunday the 19th, the Eve of St. Sebastian.

A curious additional detail: when Nabokov translated into Russian the titles of his English novels for the 1966-67 editions of Priglashenie na Kazn' and Zashchita Luzhina, he retained the English b and ia (instead of the usual Russian soft sign-уa) in Sebastian and did not decline Nait in the genitive case (the Russian spelling of the surname makes an amusing gratuitous anagram of its own: Taina Naita, Knight’s Secret, half-a-century old, born to blush unseen), suffering the whole name to sound foreign, and thus perhaps preserving the cipher

Task: invent a Christian name existing in both English and Russian which would contain a clean anagram of an English phrase that, combined with the surname, would encapsulate the novel's important strategy and would be positioned as its weathercock. Given the vertiginous difficulty of this task, the superfluous a in the anagram is so minuscule a fault that it only underscores VN’s awesome glossal power, for the whole scheme, with all its restrictions and functions, is a mind-blaster, as unlikely to be surpassed in serious literature as the closing acrostic of "The Vane Sisters." The sheer complexity of the thing stretches credulity, and it is great wonder that Nabokov designed it so cleverly and cleanly, and little, that it should have a barely perceptible limp. And even that extra article can be of employment if applied to a chessman, as it is in LATH, in the phrase that may be relevant to this note: "...or the chess set (in Pawn Takes Queen) with a missing Knight 'replaced by some

[29]

sort of counter, a little orphan from another, unknown, game?"’ (my italics, p. 83).

There is no positive proof of Nabokov's having loaded the hero's name, yet this is not mere bluster. All pieces of circumstantial evidence conspire to recommend it, not the least the rule of contraries, for to suppose that this clever and meaningful arrangement is but an unsolicited coincidence would be so much more miraculous—not unlike pulling open a combination lock by dialing one's birthday. Indeed, a coincidence of such tremendous aptness would mean nothing short of just the sort of yellow-ashen magic that is recorded in that short story about the sibylline siblings.

SCRAMBLED BACON

At the beginning of Chapter Seven of Bend Sinister, the reader is nudged to examine, one after another, three emblematic engravings of Shakespearean reference hanging above Ember's bed. On the first, "a humble fellow . . . holds a spear and a bay-crowned hat in his left hand," and the narrator's index points to the "sinistral detail" and to the "wooden voice" of the Droeshout portrait which, judging by the trimming running down what seems to be the outer side of each sleeve, gives the impression of Shakespeare having two left arms. (This observation is not universally accepted: M.H. Spielmann, a great expert in Shakespeare's portraiture, writes with scarcely veiled irritation: "... an American write was the first to declare that [the trimming] made two left sleeves—how is not apparent-and this tailor-authority has been

[30]

acclaimed with rapture and found followers even here in England among the heterodox"—Studies in the First Folio [London, 1924] 32-33). The legend "Ink, a Drug," which Ember especially values, besides containing, among other things, his friend's name, yields a bizarre but complete anagram, Grudinka, "which means 'bacon' in several languages" (93). Actually, the word means the breast, not the back of, say, a pig, but the purpose of this difficult trick is to advert, obliquely, to Bacon. The punning play on Shakespeare's presumed ghost-writer's name continues in the legend under the second picture: "Ham-let, or Homelette au Lard." The rhetorical passage that follows ("His name is protean. He begets doubles at every comer . . . Who is he? William X, cunningly composed of two left arms and a mask [i.e., on the Droeshout portrait—GB]. Who else? The person who said . . . that the glory of God is to hide a thing, and the glory of man is to find it," etc., 94) launches the great Shakespearean theme of Chapter Seven; at the same time, it sharply brings to mind Stephen's soliloquy on Hamlet in the library, in the ninth episode of Ulysses, of which the above-quoted words seem to be a capsule. (The common pointed theme of paternal love draws the two novels closer to each other than is generally recognized; that of Shakespeare's unhappy marriage, which Stephen Dedalus also belabors, wafts over Sebastian Knight's Success.)

This word-processing (grudinka—bacon—Bacon— Ham-let, etc.) may have sprung from an odd but plausible source. In Stuart Gilbert's James Joyce's Ulysses, which in his lecture on the novel Nabokov dismissed as dull nonsense (Lectures on Literature, 288) and which he had, therefore, obviously read or at least leafed through, a curious passage immediately

[31]

precedes the Shakespeare Chapter (so-called "Scylla and Charybdis"). Closing the discussion of the Luncheon episode, Gilbert evokes Finnegans Wake where, in an utter exaggeration of the same technique, Joyce shows food's disintegration through spoonerisms and anagrammatic scrambling. There, in the farrago of "kates and epas and erics and oinnos on kingclud” (that is, steak, peas, rices, onions on duckling) and such-like mush (Wake 456), one comes upon the "naboc" which must have caught Nabokov's eye as he was glancing over Gilbert's book and which, being positioned, let me repeat, only a few lines above the chapter on the Shakespeare episode in Ulysses, by sheer verbal association points to, and (for Nabokov) puns on, the Bacon controversy variously touched in Bend Sinister. Nabokov's treatment of the Droeshout portrait as a mysterious mask includes many arguments of the Baconians who "have used this portrait as evidence in favour of their thesis, calling attention to such points as the wooden appearance of the face, the peculiar dark line resembling a border between cheek and neck, and the fact that both head and collar seem to be too big for the body and appear to be floating above it, suggesting a mask. They also point out that the left sleeve of the coat is reversed, a device used in Elizabethan England to indicate a hidden message" (O.W. Driver, The Shakespearean Portraits and Other Agenda [Northhampton, 1964) 8, italics mine).

Although Nabokov read parts of Work in Progress as they appeared in the 1930s, he could not bring himself to finish Joyce's last opus, which he disliked, until much later (SO 74), and so the possibility of his having chanced upon that bit of scrambled bacon in the original book by the mid-

[32]

1940s is remote. Nor is this place to be found in the offprint Haveth Childers Everywhere (1930) presented to Nabokov by the author when the two met in 1938 (as registered in Brian Boyd's forthcoming biography of VN which I read in MS). I suppose, therefore, that Nabokov spotted the pun in Gilbert—and I mean, of course, the first (1930) edition of the book where the quotation in question appears on p. 205. If my conjecture be right—if Nabokov did take note of "naboc and erics and so on" prior to or during the composition of Bend Sinister, — then indeed the strong paronomastication effect of Joycean peculiar word-trickery, interlarded with various encoding possibilities, could have set off the chain reaction of rich Shakespearean puns in Chapter Seven and its ominous Shakespearean emblemata.

— Gennady Barabtarlo, University of Missouri

AN ETYMOLOGICAL FOOTNOTE TO CHAPTER THREE OF SPEAK MEMORY

The founder of the Nabokov family, Nabok Murza (may he flourish, "floreat," forever in his 1380), "a Russianized Tatar prince in Muscovy" (Speak, Memory 52), had a Persian name. Nabok is a northeast Iranian, or Tajik, form of the adjective nabok, "fearless," eighty per cent of which has an impeccable genetic affinity with the Russian ne boitsya, "he is not afraid." Nomen omen. The scripture of the Nabokovs' coat of arms (ˆ, "for valour" [51]) heralds the essence of the name. Whether the scripture with its hrabrost' — almost

[33]

literally bezstrashie—is a mysterious etymological insight or the unheeded echo of an old tradition, it is, in any case, a hidden sense rhyme whose pang this etymologist was delighted to feel.

— Alexander Lehrman, University of Delaware

THE REAL LIFE OF CONRAD BRENNER

Recently Gene Barabtarlo and I were talking of books, bookstores, and book collecting. When the topic of the New Directions editions of Nabokov's works came up, I mentioned I had a copy of the 1959 edition of The Real Life of Sebastian Knight because a friend of mine had written the introduction. From Gene I learned that not only did Nabokov scholars value this introduction, but that the identity of its author, Conrad Brenner, has remained a mystery to them. I have therefore arrogated to myself the privilege of offering certain recollections and reconstructions of Conrad Brenner's life to those of you who are interested.

Conrad was born in 1933 in Brooklyn, New York. He majored in English at the University of Michigan, where, in a gesture that is almost too typical of him to be believed, he dropped out in his final semester. He was drafted by the army and stationed in Germany in the early ’50s. It was there, in a base library, that he discovered an English translation of Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities. It is one of the ironies of his life that this work, which has served through the

[34]

years as his chief literary touchstone, remains only partially accessible to him since it has never been translated in full and he knows no German. A complete translation is scheduled to appear in the spring of 1991, and Conrad is apprehensive, fearing that Ulrich's mystical turn will prove to be less than revelatory.

Conrad's literary pantheon— he is a maker of lists—is not large, does not fluctuate, and centers on a few works of a few authors: Musil, selected Wyndam Lewis, Ford Madox Ford, Stendhal (especially The Charterhouse of Parma) and pre-Pale Fire Nabokov. His published oeuvre includes one introduction and two articles, all on Nabokov. "Nabokov: The Art Of the Perverse" was published in the June 23, 1958 issue of The New Republic. In it, he gives lengthy accounts of Lolita (not yet published in the U.S.), Laughter in the Dark, "That in Aleppo Once . . and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, which he credits with discrediting "forever ... the revelatory Jamesian literature which little by little discloses the kernel or 'essence' of a character" (20). Because of the New Republic article, Conrad came to write the introduction for Sebastian Knight. According to his recollection, New Directions wanted Harry Levin to write it, but for one reason or another he demurred. Someone (Nabokov?) had liked the piece and New Directions contacted him. The introduction in turn gained him one more commission. He was asked to contribute to a special Nabokov edition of the French journal L'Arc in 1964. This piece, he says, was botched in the translation. He has written a few other articles, including one on Musil, which remain unpublished.

[34]

At the time of his literary activity (late ’50s), Conrad worked at the Eighth Street Bookshop in Greenwich Village in New York. I got to know Conrad when I started working for him there in 1974. He lived alone, was aloof, intimidating, instantly judgmental, and he acted like a magnet on me. In my youthful and romantic naivete I took his studied indifference to be a strength I lacked. I saw him as a mentor, at least in the realm of literature. Because of my interest in Ezra Pound (an interest Conrad did not endorse), I also shared an interest in Pound's friends, Lewis and Ford. In 1973, Conrad founded Jubilee Press (named after the planned celebration in Musil's novel) and reprinted three titles—Lewis' Tarr (unrevised version) and The Vulgar Streak (first American edition), and Malraux’s Temptation of the West—before folding his tent. He gave me copies of all three books and recommended other novels to me, above all Musil's magnum opus. Since I read German, he gave me the German copy he owned but never could make use of.

In 1976, the bookshop burned down. I went to Iceland to pursue solitude and philological matters. Conrad went to Boston with ideas of opening his own bookshop, but changed his mind. In 1979, my wife (who also worked with Conrad at the Eighth Street Bookshop) and I moved to Seattle, and shortly thereafter Conrad came to live with us in the hopes of escaping New York for good. We argued about his smoking in the apartment and made feeble plans to open a bookstore; he offered devastatingly accurate evaluations of my own poetry and made lists of out-of-print books that deserved to see the light of day once again. I watched him spend the better part of a day composing a one-page letter on a manual typewriter asking the University of California Press for a job. It

[36]

was a beautiful letter, densely packed with the same painstaking prose exhibited in those early proclamations of love for Nabokov. But he could not find work on the West Coast and returned to his inner emigration in New York City.

In 1982, he made one final attempt at reprint publishing — Conrad Brenner Books. Among the twelve titles advertised on his pre-publication flyer are two by Ford (The Benefactor and A Call), one by Stendhal (Lucien Leuwen), and one Ford/Joseph Conrad collaboration (Romance). The number of prepublication orders did not warrant his continuing the project. He currently works in a large, mid-town Manhattan bookstore and, irony of ironies for an ex-Dodger fan, lives in the Bronx.

— William Rasch, University of Missouri

I. THE THREE SPRINGS/FOUNTAINS

Exegetes of Dar (The Gift) have been intrigued by the possible presence of Pushkin's 1827 lyric "Tri kliucha" ("The Three Springs") as an enciphered subtext behind the surface of the novel (D. Barton Johnson, Worlds in Regression 100-01; Leona Toker, The Mystery of Literary Structures 158). It has been suggested that the Pushkin poem enters Nabokov’s novel via mentions of the homonymous Russian word kliush (a "key" as well as a "spring"), consistently threaded through the verbal texture of Dar until a

[37]

thematic link between the two works becomes established. Each of Pushkin's three springs finds its counterpart in the motifs associated with Fyodor's life: the Spring of Youth (kliusch iunosti); the Castalian Spring nourishing with its swell of inspiration the exiles of the world ["Kastal'skit kliuch volnoiu vzdokhnovenia / V stepi mtrskoi izgnannikov poit j; and the Spring of Oblivion that subdues the ardor of the heart ("kliuch zabven'ia, / On slashche vsekh zhar serdtsa utolit)—the third reference according rather nicely with Fyodor's own forgetfulness about his keys (i.e. kliuchi) which effects the putting off of his ardors with Zina at the end of the novel. From a thematic standpoint, then, the proposition is a plausible one. Still, since even a thorough combing has failed to yield any direct quotations from Pushkin's poem, it may seem doubtful whether VN himself intended this connection when writing the novel.

Now, it is generally futile to inquire into an author's intentions. But one way of looking at the question might be to see if the same subtext has been used elsewhere by VN. I have come across two other occurrences of "The Three Springs" in the Nabokovian corpus, and as these have not been recorded previously let us mark them down.

The first instance appears in the French essay "Pouchkine, ou le vrai et le vraisemblable" that VN wrote on the centennial of Pushkin's death for La Nouvelle Revue Française 282 (1 March 1937: 362-78: reprinted in Magazine Littéraire 233 [Sept. 1986]: 49-54 and trans. Dmitri Nabokov, "Pushkin, or the Real and the Plausible," New York Review of Books 35 [1988] 5: 38-42). Here, the originally eight-line lyric is

[38]

rendered into French in the liberal fashion characteristic of VN's pre-Onegin method of translation:

Dans le désert da monde, immense et triste espace,

trois sources ont jailli mystérieusement;

celle de la jouvence, eau brillante et fugace,

qui dans son cours presse bouillone éperdument;

celle de Castalie, où chantea la pensée.

Mais la dernière source est I'eau d’oubli glacée ...

Despite the unexplained deletion of the two lines — essential for the Dar connection — containing the mention of thirsty exiles and the heart's ardor, the existence of the French version shows, if nothing else, that the Pushkin poem was indeed in VN's mind in early 1937 when he was putting the finishing touches to his last Russian novel. (There are other links between this essay and Dar, as well as The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, VN's next novel, but these require a new note.)

Moving on to the English fiction, in the concluding chapter of Pnin we find this account of the narrator's and Pnin’s encounter in the early twenties, at a Paris literary cafe:

It was the custom among émigré writers and

artists to gather at the Three Fountains after the

recital of lectures that were so popular among

Russian expatriates; and it was on such an

occasion that, still hoarse from my reading, I

tried not only to remind Pnin of former

meetings, but also to amuse him and other people

around us with the unusual lucidity and strength

of my memory. (179-80)

[39]

Again, the allusion to Pushkin (if there is one) is thematically motivated. A number of other Pushkin lyrics figure in Pnin. With regard to "The Three Springs" we notice the recurring motifs of a vanished youth, artistic inspiration, exile, quenching of thirst, and memory contra oblivion. But as all readers of Pnin know, the narrator's memory may be less than trustworthy. Perhaps, among other things, he has slightly misremembered the name of that cafe, which might also have been Trois sources?

A final remark: I notice that the Russian translation of Pnin (Gennady Barabtarlo with the collaboration of Véra Nabokov) renders the name of the cafe as Tri fontana" ("17 emigrantskikh pisatelei i khudozhnikov bylo zavedeno sobirat'sia v 'Trekh fontanakh'" 170). This is of course the literal sense. A fountain is not quite a spring. [Kinbote mentions "three fountains," in Zemblan "tri phantana," Pale Fire 108—CN.] Given the contextual clues, the possibility of a Pushkinian kliuch surging underneath might still be entertained.

II. THE TRUE BATCH OUTBOYS THE RIOT

One idiosyncratic and fascinating feature of Nabokov's games with quotations from other authors has to do with the phenomenon of cross-lingual homonyms. That is, VN has always been fond of teasing out hidden homophonic or otherwise sound-

[40]

related correlations between diverse languages and in this way creating unexpected links between seemingly unrelated literary texts.

A previously noted example (first pointed out by Simon Karlinsky, "Illusion, Reality and Parody in Nabokov's Plays," Nabokov: The Man and His Work 190; and afterwards by Rene Guerrat in "Vladimir nabokov v neprivychnoi ipostasi,” Kontinent 45 [1985] 374) occurs in Bend Sinister when Ember renders the beginning of a famous monologue into Russian as "Ubit il' ne ubit'?' (105). Literally, this is "to kill or not to kill," which is appropriate enough in Padukgrad, but it is also a close homophonic variant of "to be or not to be" as well as of its normal Russian rendering "byt ili ne byt." On the other hand, in the Russian original of the 1938 play The Event a character utters; "Zad, kak skazal by Shekspir, zad iz zyk veshchan” (Sobytie in Russkie zapiskt 4 [April 1938]: 80). "Zad iz zyk veshchan" is both a comically garbled variant of "that is the question" and an untranslatable Russian nonsense phrase referring to one's backside, i.e. zad. (Dmitri Nabokov translates this as simply 'That, as Shakespeare would have said, is the question," The Man from the USSR and Other Plays 209.) In VN's own, early Russian rendering of Hamlet III.i.56 the line was translated conventionally: "Byt’ ili ne byt': vot v etom vopros" (Rul' 3039 [23 Nov. 1930]: 2).

Another instance of this device that has to my knowledge eluded former commentators can be seen in Ada. Sandwiched between the more or less authentic snatches of "gipsy songs" from Russian romantic poets that Van Veen hears during his evening with Ada and Lucette in the Ursus restaurant there occur these lines:

[41]

Nadezhda, I shall then be back

When the true batch outboys the riot. . . (412)

Van calls this an "obscurely corrupted soldier dit of singular genius" and the lines are indeed corrupted. Beneath the layer of homophonic play the following source is disclosed:

Nadezhda, ia vemus' togda, kogda trubach otboi sygraet

(Nadezhda, I shall then return when the horn blower signals that the battle is over)

This is the opening of Bulat Okudzhava’s 1964 pacifist lyric—a relatively subversive thing for a Soviet poem of the mid-sixties—'"Sentimental'nyi marsh" (quoted from Proza i poeziia [Frankfurt/Main: Possev, 1968) 134). There is no military bugle blowing in Ada, but otherwise the motif of a delayed reunion in Okudzhava’s song is thematically quite appropriate to Van’s and Ada’s story. (In a recently published letter dated 21 July 1972 (Selected Letters 502] VN verifies that this is, indeed, a "marvelously garbled echo of Okujava's moving melody," but the source is not revealed.)

A final example of this playful strategy (which would merit further study) can be chosen from Selected Letters itself:

gore vidal i bit bival (468)

(in Dmitri Nabokov's translation, "I've seen woes and suffered blows," 469)

[42]

Gore Vidal, certainly. But what else?

— Pekka Tammi, Academy of Finland, Helsinki

SHOES

In Tristram Shandy (VI, 19) Sterne lists no less than eighteen varieties of shoes, but is surpassed by Nabokov. In Pale Fire we run across a bigger "collection of footgear" such as "snowboots,” "slippers,” "reversed shoes," "brown shoes," "bottekins," "Cinderella's slippers," "morocco bed slippers," "pumps," "buckle shoes," "sneakers," "shoes--mahogany red with sieve-pitted caps," "elegant jackboots of soft black leather," "loafers," "girl’s galoshes," "furred snowboots," "white wellingtons," and "booties." In Bend Sinister we trip over 'bedroom slippers," "seedy looking pumps," "slippers trimmed with moth-eaten squirrel fur," 'bloodstained arctics," "black shoes," "half boots with screwed on skates," and "old bed slippers." In several other cases Nabokov's protagonists are barefooted.

Feet and footwear have left earlier marks in Russian literature. In Eugene Onegin there is the "famous pedal digression" as Nabokov calls it, "one of the wonders of the work” (2: 115) which extends into chapters 1, 5 and 7 of Pushkin's novel in verse. In Gogol's Dead Souls chapter 7 finishes with the "Rhapsody of the Boots" (Nikolai Gogol, 1959, 83) while in chapter 8 a very charming lady is dancing on slippers. And in Gogol's "immortal" 'The Overcoat" the hero is named Bashmachkin, coming from bashmak, a shoe. But the

[43]

whole family of Akaky Akakyevich used to wear boots (so that his name, after replacing the Russian shoe by the English boot, turns into Bootkin).

Shoes are not the only garments which adorn the rich texture of Nabokov’s prose. Suits, gloves, hats, glasses and canes too appear so frequently that they seem to fit into certain opaque patterns, and the allocation of coiffures leaves the same impression. In literature pedal affairs have traversed many ages. The Greek mythology produced the Achilles' heel and motifs of the Cinderella story have been traced back for 2000 years (Neil Philip, The Cinderella Story). Welsh mythology, as preserved in The Mabinogian, made a god of blew Llaw, a shoemaker (Robert Graves, The White Goddess).

In several novels, most prominently in Pnin, Nabokov refers or alludes to the fairy tale of Cinderella (see Charles Nicol, "Pnin's History," reprinted in Critical Essays on Vladimir Nabokov). As is well known, the tale is about Cinderella’s transition from unhappiness to bliss, thanks to her merits and the lost slipper of which she can prove ownership. In Nabokov's novels the changing of shoes often coincides with the entering of a new stage of the protagonists' lives, while slippers may mark the transition to the final stage, the afterlife.

In The Gift, at the end of the first chapter, Fyodor buys new shoes, with which he will step upon the shore after crossing the Lethe, the river of oblivion, or the Styx, which river bars the entrance to the afterlife. At the end of the novel Fyodor is walking through Berlin "wearing bedroom slippers” and involved in a peripatetic discourse, a monologue on life and art which

[44]

culminates in a praise of death, being a justification for festivities. Then his left slipper falls off his heel, a clear reference to the Cinderella story. Moreover, as he kept the other slipper, his right heel remains protected, a hint at Achilles whose right heel was the only mortal part of his body (see Robert Graves, The Greek Myths [Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1955] 316). The indication of an afterlife is also presented in the poem at the very end of the novel, denoting its endlessness.

In Bend Sinister, at the turning-point of the novel when he meets his destroyer, Krug, "otherwise fully dressed," is wearing bedroom slippers which he is forced to change for a pair of half boots. At the end of the novel he enters barefoot the "immortality" the author has conferred upon him. A recurring theme in this novel is the footprint-shaped puddle which also indicates the transition to another world as it, according to D. Barton Johnson, is "the gateway between Krug's world of limited consciousness and the world of infinite consciousness inhabited by Krug's creator" (Worlds in Regression 194).

In Pale Fire the shoeing of people is cultivated as well. At the night of the dramatic departure of King Charles from his country's capital which changed his life so sweepingly, his slippers were taken away but he was lucky enough to find a pair of sneakers. In the "Foreword" Shade is visualized as eternally losing one of his "brown morocco slippers" because no indication of time is given. At the evening of his death, just after having written that he is "reasonably sure that we survive / and that my darling [his predeceased daughter] is alive," Shade is wearing "loafers" which

[45]

are shoes made of soft leather, thus approaching slippers.

These examples can be augmented by many more, for instance the "sloppy" slippers worn by a slipshod Lolita in Hunter Lane some three months before her death in Gray Star; the new shoes Lik wanted to sport in the second act, which is "all sunny weather and bright summer clothes," or the changing of the shoes of Cincinnatus before his beheading after which he "made his way in that direction where, to judge by the voices, stood beings akin to him."

So shoes seem to transport Nabokov’s main theme, the belief in an afterlife. Far from being a solution, this conclusion seems rather the beginning of many questions with respect to the plethora of feet, shoes, boots and slippers (not to speak of the skis which abound also in Nabokov's novels) which seems to cover many impenetrable patterns remaining to be unearthed.

— Gerard de Vries, Voorschoten

[46]

(7 December 1923) by Vladimir Nabokov

translated by Dmitri Nabokov

An India invisible I rule:

come 'neath the azure of my realm.

I shall command my naked wizard

to change a snake into a bracelet for thee.To thee, О princess who defies description,

I offer, for a kiss, Ceylon;

and, for thy love, my whole, luxuriant, ancient,

star-weighty firmament.My peacock and my panther, velvet sheeny,

both languish; 'round the palace,

like showers, the palmy copses patter:

we're waiting, all of us, to see thy face.

[47]

7. 12. 23.

Ia Indiei nevidimoi vladeiu:

pridi pod sinevu moiu.

Ia prikazhu nagomu charodeiu

v zapiast'e obratlt' zmeiu.Tebe, neopisuemoi tsarevne,

otdam za potselui Tseilon,

a za liubov' — ves' moi roskoshnyi, drevnii,

tiazhelozvezdnyi nebosklon.Pavlin i bars moi, barkhatno-goriashchii,

toskulut: i krugom dvortsa

shumiat,kak livni, pal'movye chashchl,

vse zhdem my tvoego litsa.

[48]

I'll give thee earings, twin teardrops of sunrise,

I’ll give the heart out of my breast.

I'm emperor, and if you don't believe it,

then don’t — but come in any case.

[49]

dam serdtse — iz moei grudi.

Dam ser'gi — dva stekaiushchikh rassveta,

la tsar', i esli ty ne verish' v eto,

ne ver', no vse ravno, pridi!

Vladimir Nabokov

Copyright © 1989 Vladimir Nabokov Estate English Version Copyright © 1989 Dmitri Nabokov

[50]

ABSTRACT

SEX AND GENDER IN NABOKOVS LOLITA: A POST-LACANIAN FEMINIST DIALECTIC

by Khani Begum

(Abstract of a paper delivered at the Annual MLA Convention, Washington, D.C., December, 1989)

Alice Jardine, in Gynesis: Configurations of Woman and Modernity, says that the crises in legitimation "experienced by the major Western narratives have not, been gender-neutral. They are crises in the narratives invented by men” (Gynesis 24). As a result, analysis of those narratives and their crises has taken the critic back to the Greek philosophies in which they are grounded leading to explication in terms of dualistic oppositions such as: Activity/passivity, Sun/Moon, Culture/Nature, Day/Night, Father/Mother, Head/Heart, Intelligible/sensitive, Logos/Pathos, Form/Matter, Man/Woman, etc. Nabokov's Lolita is one such narrative that also explicates the truths of gender and male/female sexuality within such binary oppositions, and as such it is a participant in phallocentric discourse.

Pointing to the fact that psychoanalysis was born from women’s "hystericality” and that "its most consistent emphasis has been on localizing, defining and confirming the linguistic space of the Other" (89-90), Jardine claims that Lacan, like Freud, was never able to fathom the "dark continent" of female sexuality and his theories of absolute sexual difference never moved beyond the male subject as absolute metaphor. Perceived in terms of the dialectic between Lacanian psychoanalysis and contemporary feminist criticism, Nabokov's Lolita functions as a

[51]

representation of the Other. Before the feminist critic and reader can find meaning that is not gender inflected in Lolita she/he needs to open up a new space, one that either circumvents or goes beyond binary oppositions in their traditional sense. [This paper attempts to open up that space in order to re-examine Nabokov's Lolita for the hidden silences that reveal a "sub-text" beyond traditional conceptions of gender and sex relations.] Jardine finds such a process, namely, "gynesis," the putting into the discourse of "woman," or a process that valorizes the feminine, to be intrinsic to the condition of modernity. While feminist critics have objected to the Lacanian conception of woman as the Other, some of Lacan's defenders (like Catherine Clement) have posited that this is exactly what feminism is about, that women should not be abstracted, idealized, and universalized. Also, in perceiving woman as not Subject, she is actually freed from the binary opposition and can be perceived in Luce Irigaray’s terms as "the sex which is not one." Hence a strain of post-Lacanian feminist psychoanalysts who posit their feminism on the notions of difference see in this view multiple states rather than binary ones.

This paper employs Lacanian and Feminist readings concurrently to analyze, through the interactions of the male subject and the female Others in the novel, Nabokov's own subconscious desire for achieving transcendence through literature. The disagreement produced out of the feminist and the psychoanalytic interpretation points towards what Jardine calls a "post modem" writing about interpretation. The feminist discourse, primarily political, is brought together with the analytical in a mutual desire for explicating, what Derrida calls, the "truth in fiction."

Youngstown State University

[52]

V.V. Nabokov in the USSR A Bibliography of Sources: 1976-1981

by N. Artemenko-Tolstaia and E. Shikhovtsev

[The first segment of this bibliography, 1922-1975, appears in issue #23 (Fall 1989). Citations are transliterated; commentaries are translated from the Russian.]

1976

92. Bitov, A. Ptitsy, ili Novye svedeniia о cheloveke. [povest'] In his book: Dni cheloveka. Povesti Mos: Molodaia gvardiia, p. 318. (mention of "Vladimir Vladimirovich a").

93. Bitov, A. Sem' puteshestvii. Len: Sov. pisatel', p. 554. (Reprint of #7la).

94. Bursov, B. Kritika kak literatura. Len: Lenizdat, p. 99. (Reprint of #73 with changes).

94a. Mauler, F.I. "Nekotorye sposoby dostizheniia ekvilinearnosti [on the nature of the English translation of Eugene Onegin]. In Tetradt perevodchika* 13th edition. Mos: Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniia, p. 13. [Nabokov's translation is mentioned in a cursory manner without reference to his name]

[53]

95. Mikhailov, О. Strogii talant. Ivan Bunin. Zhizn. Sud'ba. Tvorchestvo. Mos: Sovremennik, pp. 187, 263-266, 277. [Separate passages from #66 and #79 are reprinted in the text with changes]

96. Muliarchik, A.S. "Smena literaturnykh epokh" [Literature in the USA from the "Angry 30s" to the "Revolutionary 60s"]. Voprosy literatury, no. 7 (July), pp. 80, 105-109. [for reprints see #207, #238]

96a. Muliarchik, A.S. and I.Khassan, "Sovremennaia amerikanskaia literatura. 1945-1972. Vvedenie." Obshchestvennye nauki za rubezhom. Ser. 7, Literaturovedenie, no. 1 (January-March) p. 274.

96b. Nikoliukin, A.N. Teoriia romana [Sbornik statei]. Obshchestvennye nauki za rubezhom. Ser. 7, Literaturovedenie, no. 3 (July-September) p. 109.

97. Pugachev, V.V. "Pushkin i Adam Smit." In SravniteVnoe izuchenie literatyr. Sb. statei k 8-letiiu akad. M.P. Alekseeva. Len: Nauka, p. 238 (footnote 4).

98. Solotaroff, T. "Trebovaniia vremeni obiazyvaiut nas obratit'sia k real'nosti." Inostrannaia literatura, no. 4 (April) p. 225.

98a. Chuprinin, S. "Logika alogizma.” Literaturnoe obozrenie, no. 2 (Feb) p. 76. [article in a discussion concerning A. Voznesenskii, with citations from #58. For reprint see #213].

99. Epshtein, M. "V poiskakh 'estestvennogo' cheloveka. 'Seksual'naia revoliutsiia' i degumanizatsiia lichnosti v zapadnoi literature XX veka." Voprosy literatury, no. 8 (August) p. 131-134.

[54]

1977

100. Alekseev, M.P. "Zametki na poliakh. 2. Epigraf iz E. Berka v 'Evgenil Onegine’." In Vremennik Pushkinskoi komissit 1974. Len: Nauka, pp. 102-104, 107-108.

100a. Vol'pert, L.I. "Bomarche v tragedii ’Motsart 1 Sal'eri." Izv. AN SSSR. Ser. lit-iy i lazyka, t. 36, no.3 (May-June) p. 244-245 [reprinted In #145, pp. 179-180, 182].

101. Grigor’ev, A. Russkaia literatura v zarubezhnom Itteraturovedenif. Len: Nauka, p. 155 (footnote 38), 291.

102. Kataev, V.P. Izbra. proizv v 3-kh t, t. I, Mos: Khudozhestv. literatura, p. 486-487. [reprint of #45].

102a. Kraineva, I.N. "Natural’naia shkola v zaru-bezhnoi rusistike." Russkaia literatura, no. 2 (Apr-Jun) p. 208-209.

103. Libman, V.A. Amerikanskaia literatura v russkikh perevodakh i kritike. Bibliografiia. 1776-1975. Mos: Nauka, pp. 30, 382.

104. Mendel'son, M.O. Roman SShA segodnia. Mos: Sov. plsatel', pp. 43, 235-236, 397. [reprint of #90 with changes]

105. Molchanov, V. "Korroziia vechnoi metafory" (O 'rolevykh' kontseptsiiakh v zapadnom

[55]

literaturovedenii i kul'turologii). Voprosy literatury, no. 4 (April) p. 141.

106. Shtainberg, V. Shliapa komissara [roman]. In Sovremennyi detektiv GDR. Mos: Progress, pp. 52, 76 [reprinted in #167]

Posthumous bibliography

1977

107. Allen, U. "Postskriptum k Traditsii i mechte'." Inostrannaia literatura, no. 12 (Dec) p. 213-214.

108. Muliarchik, A. "Neskol'ko slov po povodu stat’i Uoltera Aliena.” Inostrannia literatura, no. 12 (Dec) p. 218-219.

108a. Cherichenko, L.L. and R. Detweiler, "Priem igry v sovremennoi amerikanskoi proze." Obshchestvennye nauki za rubezhom. Ser. 7. Literaturovedenie, no. 4 (Jul-Aug), p. 69-70.

1978

109. Anastas’ev, I. "Uroki bibliograpii." Voprosy literatury, no. 11 (Nov) p. 292.

110. Borovik, G. "Rastliteli" (Industriia, ubivaiushchaia dushi). Moskovskaia pravda (12 August) p. 3. [reference to the pornographic journal "Lolita" without any reference to Nabokov's Lolita].

111. ____________. "'Sekspluatatsiia' detei.” Argumenty i fakty, no. 9 (Sept), p. 2 [reprint of #110].

[56]

112. Gardner, M. "Annotirovannaia ’Alisa.' Vvedenie." In Kerroll L. Prikliucheniia Alisy’ v Strane Chudes. Skvoz zerkalo i chto tam uvidela Alisa, ili Alisa v Zazerkal'e. Ser. Lit. pamiatniki. Mos: Nauka, p. 255.

113. Gorianin, A.B. "Mnogoiazychie." In Kratkaia literaturnaia entsiklopediia v 9-ti t., t. 9, Mos: Sov. Entsiklopedia, p. 539-540.

114. Dmitriev, A.B. and E.V. Bolbovskaia. "Alfabitnyi predmetno-imennoi ukazatel' k tt. 1-9 KLE'". In KLE, t. 9 [see #1131pp. 896, 929.

115. Isaev, A. [Shikhovtsev, E.B.]. "Primyk nam fakel, pervokursnik!." Mendeleevets (Moskva), tip. Mosk. khim-tekhnol. in-ta im D.I. Mendeleeva, no. 23 (8 Sep) p. 3 [Citation of the closing sonnet in The Gift, without quotation marks or any sort of reference]

116. Kataev, V.P. "Almaznyi moi venets." Novyi mir, no. 6 (July) p. 98. [reprinted in #136, #161, #224].

117. Kondratov, A. Zvuki i znaki Biblioteka'Znanie'. fed. 2-e, per. Mos: Znanie, p. 189.

118. Krasavchenko, T.N. "Angliiskaia i ameri-kanskaia kritika 70-kh godov о Pushkine.” (Obzor). In Zarubezhnoe literaturovedenie i kritika о russkoi klassicheskoi literature. Referativnyi sbornik. Mos: fed. INION AN SSSR, p. 69.

119. Lilli, I.K. i B.P. Sherr, ’’Zarubezhnaia literatura po russkomu stikhovedeniiu, izdannaia s 1960 g. Materialy i bibliografii.” In Issledovantia po teorii stikha. Len: Nauka, p. 226.

[57]

120. Melen'tiev, IU.S. "Filosofiia N.G. Chernyshevskogo i nekotorye voprosy sovremennoi ideologicheskoi bor'by." Voprosy filosofii, no. 6 (Jun) p. 55. [At the plenary session of the All-Soviet Scientific Conference, "The Theoretical and Literary Legacy of N. G. Chernyshevskii and the Present," May 25, 1978 in Leningrad, the Minister of Culture of the RFSFR, YU. S. Melen'tiev, delivered the speech, "The Philosophical Outlook of N.G. Chernyshevsky and Several Questions on the Contemporary Ideological Struggle." See Russkaia literatura, no. 4, p. 210. [reprinted with changes in #2251

121. Motyleva, T. "Svobodnaia forma." Voprosy literatury no. 12 (Dec) p. 171.

122. Muliarchik, A.S. "O vzaimovlianii dvukh kul'tumykh traditsii." SShA. Ekonomika. Politika. Ideologiia, no. 2 (Feb) pp. 69-79.

123. Murav'iev. V.S. "Berdiaess." In KLE, t. 9 [see #113], p. 121.

124. ____________. "Perevody i izdaniia russkoi I sovetskoi literatury za rubezhom." In KLE, t.9 [see #113], p. 607.

125. Ovcharenko, A. "Razmyliaiushchaia Amerika." Novyi mir, no. 12 (Dec) p. 246.

126. Sedakova, O.A. "N.V. Gogol' v sovremennoi zarubezhnoi kritike." (Obzor). In Zarubezhnoe... [see #118], p. 107.

[58]

127. Tropov, V. "Movizma osen' zolotaia. Podrazhanie Kataevu." Lit obozrenie, no. 10 (Oct) p. 58.

127a. Cherichenko, L.L. and K.N. Kenner. "Amerikanskie pisateli-modernisty.” (see citation in #108a], no. 3 (May-Jun) p. 177.

128. Sharypkin, D.M. "Pushkin i 'Nravouchitel'nye rasskazy’ Marmontelia." In Pushkin. Issledovaniia i materialy, t. VIII. Len: Nauka, pp. 108, 118, footnote 302.

1979

129. Anonymous. "Nabokov VI. VI.” Sov. entsiklopedicheskii slovar'. Mos: Sov. entsiklopediia, pp. 862-863. [Reprinted in #144, #156].

130. Anonymous. "Poemy Pushkina v angliiskom perevode." Inostrannaia literutura, no. 3 (Mar) p. 278.

131. Voznesenskil, A. Izbrannaia lirika. (Poeticheskaia biblioteka). Mos: Detskaia literatura, p. 108 [reprinted in #132].

132. Voznesenskii, A. "Mat'." Kolymskaia pravda, 2 July, (reprinted in #131, 133, 198, 216a, 231]. [This poem was read by the author August 29 on program I of the All-Union Radio Network and at the end of 1979 or the beginning of 1980 on the National Television Network on the occasion of an evening devoted to the author: the program was later re-telecast].

133. ____________. Soblazan. Stikhi. Mos: Sov. pisatel’, p. 15. [reprint of #132]

[59]

134. Dzhonston, Ch. On October 14 an interview of Ch. Dzhonston was telecast on the National Television Network [reference to him in #180). He mentioned Nabokov's translation of Eugene Onegin as a too literal word for word translation.

135. Zverev, A.M. Modemizm v literature SShA. Formirovanie, evoliutsiia, krizis. Mos: Nauka, pp. 216-218, footnote p. 318 [abridged reprint of #65a]

136. Kataev, B.P. Almaznyi moi venets. Mos: Sov. pisatel', pp. 216-218. [reprint of #1161

137. Likhachev, D.S. "Sady Litseia." In Pushkin. Issledovaniia i materiali t. IX, Len: Nauka, p. 188, footnote p. 349.

138. Lotman, M. "Nekotorye zamechaniia о poezii i poetike F.K. Godunova-Cherdyntseva." In Vtorichnye modeliruiushchie sistemy. Tartu: izd. Tartuskogo gos. un-ta, pp. 45-48.

139. L'osa, M.V. Tetushka Khuliia i pisaka [roman]. Inostrannaia literatura, no. 11 (Nov), p. 170; in the same book are footnotes by the translator, L. Novikova, regarding the common noun usage of the name "Lolita.”

140. Mashinskii, S. Khudozhestvennyi mir Gogolia. Posobie dlia uchitelei. Second edition. Mos: Prosveshchenie, pp. 418-420 and footnote page 429. [reprint of #56]

141. Muliarchik, A. "Krizisnye semidesiatye? Beseda v redaktsii: Osnovnye tendentsii v sovremennoi

[60]

literature Anglii i SShA." Inostrannaia literatura, no. 10 (Oct) p. 209.

142. Plekhanov, S. "Anatol’ Kuragin, vozvedennyi v Pechoriny?” Literaturnaia gazeta, no. 1 (Jan 1), p. 5. [The usage of "Lolita" as a common noun] [reprinted in Plekhanov's 1986 book]

143. Khassan, I. "Posle 1945 goda." In Literaturnaia istoria SShA v 3-x t. T. III. Mos: Progress, p. 562 and footnote p. 628. [Index of names compiled by V.A. Libman]

1980

144. Anonymous. "Nabokov." In SES (see #129), latest edition.

145. Vol'pert, L.I. Pushkin i psikhologicheskaia traditsiia vo frantsuzskoi literature. (K probleme russko-frantsuzskikh literaturnikh sviazei kontsa XVIII-nachala XIX vv.). Tallin: Eesti raamat, pp. 46, 173, 179-180, 182. [includes #100a with insignificant changes]

146. Evtushenko, E. Izbr. proizv. v 2-kh t t.2, Mos: Khudozhestv. literatura, p. 322. [reprint of #59 and #88]

147. Zverev, A.M. Pinchon: sbornik statei. Ref. zhurnal Obshchestvennye nauki za rubezhom. Ser. 7. Literaturovedenie. no. 2 (Mar-Apr) p. 172.

148. Kuznetsov F. "Rodoslovnaia nashei edei. Revoliutsionno-demokraticheskaia kritika i

[61]

sovremennost'." Lit gazeta, no. 43 (22 Oct) p. 4. [reprinted in #203]

149. Lotman, IU.M. Roman A.S. Pushkina EVGENII ONEGIN. KommentariL Posobie dlia uchitelia. Len: Prosveshchenie, pp. 12, 31, 207-208, 228, 380. [reprinted in #205]

150. Makeev, A.V. "Russkaia klassicheskaia literatura v krivom zerkale angliiskogo i amerikanskogo literaturovedeniia." Vestnik Mosk. un-ta. Ser. 9. Filologiia, no. 1 (Jan-Feb), p. 19.

151. Muliarchik, A. Poslevoennye amerikanskie romanisty. Mos: Khud. lit., p. 34. [Allusionary usage of a phrase from Lolita, cited in #96. The manuscript contains a passage about Nabokov in a clumsy, obvious way, but it does not appear in the text]

152. Nikoliukin, A.N. "Amerikanskii roman v XX veke." Ref. zhurnal Obshchestvennye nauki za rubezhom. ser. 7. Literaturovedenie, no. 1 (Jan-Feb), pp. 145,148.

152a. Stroev, A. "Alen Rob-Griie. Tsareubiitsa." Sovremennaia khudozhestvennaia literatura za rubezhom. Inf. sbornik, no. 4/142 (Jun-Aug), pp. 63-64.

153. Tvardovskii, A. Sobr. soch v 6-ti t. t.5. Mos: Khud. lit., pp. 79-80. [reprint of #31]

154. Khrapchenko, M.B. Sobr. soch v 4-kh t. t.l. Mos: Khud. lit., pp. 679, 681-683, 686, footnote on 708. [reprinted in #227]

[62]

155. "Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin in a New English Translation" (discussion). Soviet Literature, no. 2 (Feb), pp. 150, 154, 156. [Nabokov's name is mentioned in the editor's foreword and in the comments by I. Zhelanova and R Deglish)

1981

156. Anonymous. "Nabokov". In SES (see #129), latest edition.

157. Arenshtein, L.M. and IU.D. Levin. "Perevody I izuchenie Lermontova za rubezhom." In Lermontovskaia entsiklopediia. Mos: Sov. entsiklopedia, p. 390.

158. Evtushenko, E. "Neobiazatel’no liubit’ tol’ko bol'she derev'ia. Parizhskie zametki." Lit. gazeta, no. 29 (15 Jun), p. 15. [reprinted in #1991

159. Zasurskii IA. "V razdum'iakh о budushchem. Besedi s amerikanskimi pisateliami." Lit. gazeta, no. 2 (7 Jan), p. 15.

160. Zubkov, N.N. "O vozmozhnykh istochnikakh epigrafa k Bakhchisaraiskomu fontanu." In Vremennik Pushkinskoi komissii. 1978. Len: Nauka, 1981, p. 110-111.

161. Kataev, V. Almaznyi moi venets. Povesti. Mos: Sov. pisatel', p. 150. [reprint of #1161

161a. Kuleshov, V.V. "Uproshchenie slozhnogo" [about D. Fanger’s The Art of Gogol]. In Russkaia literatura v

[63]

otsenke sovremennoi zarubezhnoi kritiki. Mos: Izd. Mosk. gosud. un-ta., p. 284.

162. Kushner, A. Kanva. Iz shesti knig. Len: Sov. pisatel’, p. 130. [reprint of #891

163. (Lakshin, V.). "F.M. Dostoevskii i morovaia literatura. Beseda v redaktsii.” Inostrannaia literatura, no. 1 (Jan) p. 197.

164. Levin, IU.D. "Novyi angliskii perevod Evgenii Onegin." Russkaia literatura, no. 1 (Jan-Mar), pp. 220-225.

165. Muliarchik, A. "Pered vyborom. Вогbа realizma i modernizma v literaturnoi zhizni SShA." Lit. ucheba, no. 5 (Sep-Oct), pp. 172, 176.

165a. Pomerantseva, E.S. "Sovremennyi angliiskii roman". Ref. zhurnal Obshchestvennye nauki za rubezhom. Ser. 7. Literaturovedenie, no. 4 (Jul-Aug), p. 177.

165b. Puchkova, G.A. "Neravnotsennye etiudy о klassikakh." [Concerning the collection, Russian Literature of the 19th Century: Essays, ed. J. Fennel] In Russkaia literatura... (see #16la), p. 162.

165c. Sarukhanian, A. "Shon O'Faolein. I opiat?" Sovremennaia khudozhestvennaia literatura za rubezhom. Inf. sbornik, no. 4 (Jun-Aug), p. 27.

166. Feinberg, I. "Arap Petra Velikogo.” In his book, Chitaia tetradi Pushkina. Izd. 2-e. Mos: Sov. pisatel', pp. 72-73, 92-93, 99-101. [reprinted in #212, #243] [A

[64]

speech delivered at the Pushkin Museum, Moscow, November 3, 1970]

167. Shtainberg, V. "Shliapa komissara...” (reprint of #106).

167a. Shuripa, N. "Ierun Brauvers. Cherovye nabroski." Sovremennaia... (see #165b), no. 5 (Sep-Oct.), p. 51.

The last installment of the bibliography, 1982-1985, will appear in the next issue of The Nabokovian.