Download PDF of Number 25 (Fall 1990) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 25 Fall 1990

____________________________________

CONTENTS

News

by Stephen Jan Parker 3

Moscow/Leningrad Host the First

International Nabokov Conference

by Stephen Jan Parker 12

Nabokov on the Moscow Stage

by Brett Cooke and Alexander Grinyakin 22

V.V. Nabokov in the USSR 1982-1985

by N. Artemenko-Tolstaia and E. Shikhovtsev 26

Annotation & Queries

by Charles Nicol Contributors:

Alexander Dolinin, S. E. Sweeney,

Manfred Voss, Priscilla Meyer 37

Vladimir D. Nabokov and Capital Punishment

by Gennady Barabtarlo 50

1989 Nabokov Bibliography

by Stephen Jan Parker. 63

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 25, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

[3]

News

by Stephen Jan Parker

The Nabokovian has featured only those publications, such as Michael Juliar's Bibliography, which are deemed essential sources for Nabokov scholarship. Such is the case with the publication on October 15 of Brian Boyd's Vladimir Nabokov. The Russian Years (Princeton University Press), as excerpts from some of the advance and early reviews attest:

"This is the first comprehensive account of Nabokov's life and oeuvre. The book's wide-ranging research and deep affinity for Nabokov's writings should establish it as the single indispensable source on its subject for many decades to come." Simon Karlinsky

"I cannot decide what to admire most: the dazzling array of facts which Brian Boyd managed to gather, the care and sensibility of his reading, or the independence of his judgment and style. I am certain that he will not only have written the authoritative work on Vladimir Nabokov, but one of the great literary biographies of this century." Dieter E. Zimmer

"A benchmark of biographical excellence." "Masterly, inspiring first volume of a two-volume critical life of Nabokov that lays open the heart and art of a writer as have few biographies since Richard Ellmann's James Joyce." Kirkus

[4]

"Nabokov’s life reads like a work by a very imaginative creator. Mr. Boyd gives us that life and ventures many shrewd glimpses beyond it. As a biography his book can hardly be surpassed. It is a definitive life of the man and a superbly documented chronicle of his time. We will not need another biography of Nabokov for the forseeable future. Sergei Davydov, New York Times Book Review

The second, concluding volume of the biography is scheduled for publication in fall 1991.

*

The 1990 Nabokov Society meetings will be held in Chicago in association with the annual national convention of the Modem Language Association:

(1) Friday, 28 December, 8:30 - 9:45 am, Picasso Room, Hyatt Regency Hotel. "Vladimir Nabokov as Stylist. (Commemorating the Fiftieth Anniversary of Nabokov's Emigration to America)." Samuel Schuman (Guilford College) presiding. Papers by Roy C. Flannagan (Southern Illinois University), John Burt Foster, Jr. (George Mason University), Shawn Rosenheim (Williams College), William Monroe (University of Houston).

(2) Sunday, 30 December, 1:45 - 3:00 pm, Picasso Room, Hyatt Regency Hotel. "Nabokov and Romanticism." Edith Mroz (Delaware State College) presiding. Papers by James O'Rourke (Florida State University), Philip Sicker (Fordham University), Marilyn Edelstein (Santa Clara University), Edith Mroz (Delaware State College).

Because the MLA denied our request that the two sessions be scheduled consecutively, as has been the practice in recent years, the brief business meeting of

[5]

the Vladimir Nabokov Society will be conducted following the first meeting (Friday, 28 December), 9:45 - 10:00 am.

The preliminary program of the AATSEEL national convention does not indicate a session sponsored by the Vladimir Nabokov Society.

*

At the annual convention of the American Society for the Advancement of Slavic Studies (AAASS) which took place in Washington, DC on October 18-21, there was a panel on "Nabokov and the Fairy Tale," at which the following papers were given: Priscilla Meyer (Wesleyan University), "Pale Fire and Isak Dinesen, or Nattochdag, You Are the One"; Gennady Barabtarlo (University of Missouri), "The Enchanted Hunter"; and, Susan Elizabeth Sweeney (College of the Holy Cross), "Another Version of the Same Banal Legend: Enchantment in Lolita."

*

In order to facilitate the designation of topics for future Nabokov Society meetings, given below is a complete listing of past session topics:

1978: "New Directions in Nabokov Criticism"

1979: "Nabokov: Current Critical Approaches"

1980: "Speak On, Memory: Problems of Autobiography as Fiction in the Novels of Vladimir Nabokov"

1981: "Nabokov... and Others"

1982: "The Role of Games in Nabokov"

"Vladimir Nabokov: Aesthete and/or Humanist"

1983: "Lovers, Muses, and Nymphets: Women in the Art of Nabokov"

[6]

"Nabokov and the Russian Emigré Literary Scene"

1984: "Nabokov and the 'Passion of Science'" "Nabokov and Cultural Synthesis"

1985: "Nabokov: Poet, Playwright, Critic, Translator" "Lolita at Thirty"

1986: "Translated Things: Nabokov's Art as Translation and in Translation"

"Nabokov and the Short Story"

"Nabokov on Freud and Freud on Nabokov"

1987: "The Posthumous Nabokov"

"Nabokov, Philosophy, and the Arts" "Authorship and Authority: Nabokov's Artistic Control"

1988: "Nabokov and Contemporary Critical Theories"

"Nabokov and Others: Affinities and Arguments"

"Nabokov's Poetics"

1989: "Sexuality in Nabokov's Narrative" "Approaches to Teaching Nabokov"

"Nabokov as Critic"

1990: "Vladimir Nabokov as Stylist"

"Nabokov and Romanticism"

*

Mrs. Jacqueline Callier and Dmitri Nabokov have provided the following list of VN works received October 1989 - September 1990.

October — Drugie Berega [Speak, Memory). Moscow: Knizhnaia Palata.

— Transparent Things. New York: Random House, Vintage International.

[7]

December — Autres rivages [Speak, Memory], tr. Yvonne Davet and Mirese Akar. Paris: Gallimard, revised text with annotations.

— Vladimir Nabokov/Elena Sikorskaja. Nostalgia. Milano: Rosellina Archinto, unauthorized edition.

— Lolita. Berlin: Ex Libris.

— Lolita. New York: Random House, Vintage International.

— Pnin. New York: Random House, Vintage International.

January — Laughter in the Dark. New York: Random House, Vintage International.

— 48 Poems. In Moskva [USSR], no. 6, 1989.

— "Ada und Van" [excerpt]. In Der Rabe [Germany], no. 26, 1989.

— Priglashenie na kazn'. Zashchita Luzhina. Rasskazy. [Invitation to a Beheading, The Defense, Stories.] Kishinev [USSR].

February — Ada. New York: Random House, Vintage International.

March — Strong Opinions. New York: Random House, Vintage International.

April — Bend Sinister. New York: Random House, Vintage International.

[8]

— Feu Pale [Pale Fire]. Paris: Gallimard, collection "L'lmaginaire” second printing.

— Lolita. London: Penguin reprint.

— A Russian Beauty and Other Stories. London: Penguin reprint.

— The Real Life of Sebastian Knight. London: Penguin reprint.

— Bend Sinister. London: Penguin reprint.

— Invitation to a Beheading. London: Penguin reprint.

— Glory. London: Penguin reprint.

— Lolita. London: Penguin reprint.

— Excerpts from Lolita. In Schamlos Schon. Zwolf erotische Phantasien. Munich: Wilhelm Heyne.

June — Transparencies [Transparent Things], tr. Margarida Santiago. Lisbon: Editorial Teorema.

— Lolita. Paris: Gallimard, Folio, 14th reprint.

July — Transparent Things. London: Penguin reprint.

— Laughter in the Dark. London: Penguin reprint.

August — Look at the Harlequins!. New York: Random House, Vintage International.

[9]

— Nabokov's Dozen. London: Penguin reprint.

— Nikolaj Gogol, tr. Jochen Neuberger. Vladimir Nabokov Gesammelte Werke. Reinbeck bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

— Das Bastardzeichen [Bend Sinister], tr. Dieter Zimmer. Vladimir Nabokov Gesammelte Werke. Reinbeck bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

— Skosnie w Lewo [Bend Sinister], tr. Maciej Slomozynski. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo CDN.

— The Defense. New York: Random House, Vintage International.

September — Lolita [parts 1,2]. In Moldavia literaturnaia, [USSR] no. 12, 1989 and no. 1, 1990.

— Pod znakom nezakopogozhdennikh [Bend Sinister]. In Ural [USSR] no. 1, 2, 3, 1990.

— Korol’, dama, valet [King, Queen, Knave]. In Volga [USSR], no. 2, 3, 1990.

— The Enchanter [Hungarian], In Nagy Vilag, no. 3, 1988.

— A Verdadeira Vida de Sebastian Knight [The Real Life of Sebastian Knight], tr. Ana Luisa Faria. Lisbon: Dom Quixote.

[10]

— Time and Ebb/Le Temps et Le reflux [stories], tr. Ann Grieve. Paris: Presses Pocket: bilingual edition with preface and notes to "Time and Ebb," "The Vane Sisters," "That in Aleppo Once...”, "Signs and Symbols."

— Pokana za ekzekutsiia [Invitation to a Beheading, The Defense, Other Shores], tr. from Russian Penka K'neva. Sofia, Bulgaria: Narodna kultura.

*

Books announced this fall:

Vladimir Alexandrov. Nabokov's Otherworld. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

D. Barton Johnson, ed. Russian Literature Triquarterly. No. 24. Special Nabokov Issue. Ann Arbor: Ardis.

Ellendea Proffer, ed. Vladimir Nabokov. A Pictorial Biography. Ann Arbor: Ardis.

Christine Rydel. A Nabokov's Who’s Who. Ann Arbor: Ardis.

*

Ardis (2901 Heatherway, Ann Arbor, MI 48104) announces the availability of the following Nabokov works in Russian:

Blednyi ogon'

Perepiska s sestroi Pnin

Sobranie sochinenii. Vol. I. Korol', dama, valet

[11]

Sobranie sochinenit Vol. VI. Dar

Sobrante sochinenit Vol X. Lolita

Sogliadatai

Vesna v Fial'te

Vozvrashchenie Chorba

Forthcoming in Russian:

Sobranie sochinenit Vol. III. Sogliadatai. Volshebnik

Sobranie sochinenit Vol IX. P’esy

*

Our thanks to Ms. Paula Malone and Ms. Lisa Walther for their invaluable aid in the preparation of this issue.

[12]

MOSCOW/LENINGRAD HOST THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL NABOKOV CONFERENCE

by Stephen Jan Parker

The idea for the first international Nabokov conference was bom at Middlebury College in conversations between Nikolai Anastas’ev, Viktor Erofeev, Vladimir Alexandrov, and David Bethea. Once the committment was made, the hosts designated Natalia Izosimova as their coordinator, and Vladimir Alexandrov agreed to serve as coordinator for foreign participants; assistance in obtaining visas and arranging Moscow logistics was provided by Ms. Dulce Murphy of the Esalen Institute, San Francisco. The conference sponsors were the journal, Inostrannaia literatura (Foreign Literature), and the newly constituted cultural organization "Mir Kultury" (World of Culture). The conference proper was scheduled for May 28-30 in Moscow, to be followed by Nabokov-related events in Leningrad, May 31-June 1.

Not without some trepidation, participants converged on Moscow during the weekend of May 26-27, uncertain as to where they would be housed and fed, the site of the conference, and the final program. Assurances had been given that participants would be met on arrival in Moscow, and that by that time all details would be worked out. As it turned out, the Russian organizers surpassed expectations in their organization of the conference. Participants in Moscow were housed in the apartments of various staff members of Inostrannaia literatura. The exceptionally warm hospitality shown by each of the hosts set the tone for the entire week. Lunches were provided at the Writer's Club of the Union of Soviet

[13]

Writers, and a lavish evening banquet at Tsaritsyn, on the outskirts of the city, capped the Moscow agenda.

The opening day sessions were held in the Rakhmaninov Hall of the Moscow Conservatory. Because the hall was needed subsequently for Conservatory examinations, the other sessions were held in a large adjacent conference room, around a table which sat 20-25 persons. Morning sessions were scheduled 11:00 am - 2:30 pm; afternoon sessions, 4:30 - 7:30 pm. Attendance ranged from 50 to 100 persons per session. The conference program was as follows:

MONDAY, MAY 28

Nikolai Anastas'ev Welcoming remarks from the editor of Inostrannaia literatura

"Nabokov's Return to Russia"

Nikolai Samvelian Welcoming remarks from the President of "Mir Kultury"

Vladimir Alexandrov "Nabokov and Otherworldliness"

Alexander Dolinin On time and space, point of view, and otherworldliness in VN's writings

David Bethea "Nabokov and Brodsky: Two Butterfly Poems"

George Nivat On Nabokov's poetry

Leszek Engelking "Time in Invitation to a Beheading"

Alexander Zverev "Nabokov's Berlin"

TUESDAY, MAY 29

Brian Boyd "V.D. Nabokov and V.V. Nabokov: Father and Son, Life and Death, Life and Art."

Vladimir Solov'ev "Nabokov's Letters"

[14]

Viktor Erofeev "Nabokov's Pronouns“

Ellen Pifer "Nabokov's Children: The Immortal and the Immature"

Robert Alter "Voluntary Memory and Nabokovian Prose"

Sergei Davydov On the Chernyshevskii section of The Gift

Ivan Tolstoy On Nabokov’s short stories

Vimala Ramarao On "Cloud, Castle, Lake"

D. Barton Johnson "’L'Inconnue de la Seine' and Nabokov's Naiads"

Galya Diment "Nabokov and Joyce"

WEDNESDAY, MAY 30

Mikhail Meilakh "Russian Sub-texts in VN's English Novels"

Stephen Jan Parker "Nabokov's Montreux Books: Part II"

David Rampton "Nabokov as Critic"

Julian Connolly "The Gaze of the Other in Nabokov's Russian Prose"

Vadim Stark On Valentina Shulgina

On the evening of May 30 the participants and several of their Russian hosts boarded the overnight train to Leningrad: an impromptu party ensued in the private and comfortable sleeping car. At 7:00 am, Thursday, May 31 they were met at the Leningrad station and bussed to the hotel "Moskva." Following check-in and snack, the afternoon was spent on a bus tour of city sites connected with VN and his family, accompanied throughout by Vadim Stark's remarkable, thorough narration. The itinerary included a lengthy stop at the site of the Nabokov residence on Gertzen Street (previously Morskaya Street) and a visit to the past site of the Tenishev

[15]

Academy. Dinner was held at Ivan Tolstoi's apartment, hosted by he and his family.

Participants had been informed for the first time during the train ride to Leningrad that an "evening" had been arranged in Leningrad and that each of them was expected to participate. At 7:30 on Thursday, the "Grand Nabokov Evening" was held in the majestic setting of the main hall of the Nikolaevsky Palace. The event, widely publicized throughout Leningrad, drew an audience of approximately 250 persons of all ages. The participants (now joined by Dieter Zimmer) sat on a stage facing the audience, and each in turn delivered remarks (hastily prepared) in response to the general question, "Why Nabokov?,” and then answered questions from the audience. Alexander Dolinin served ably as moderator, with the assistance of Evgenii Belodubrovsky. The "Evening" lasted more than four hours.

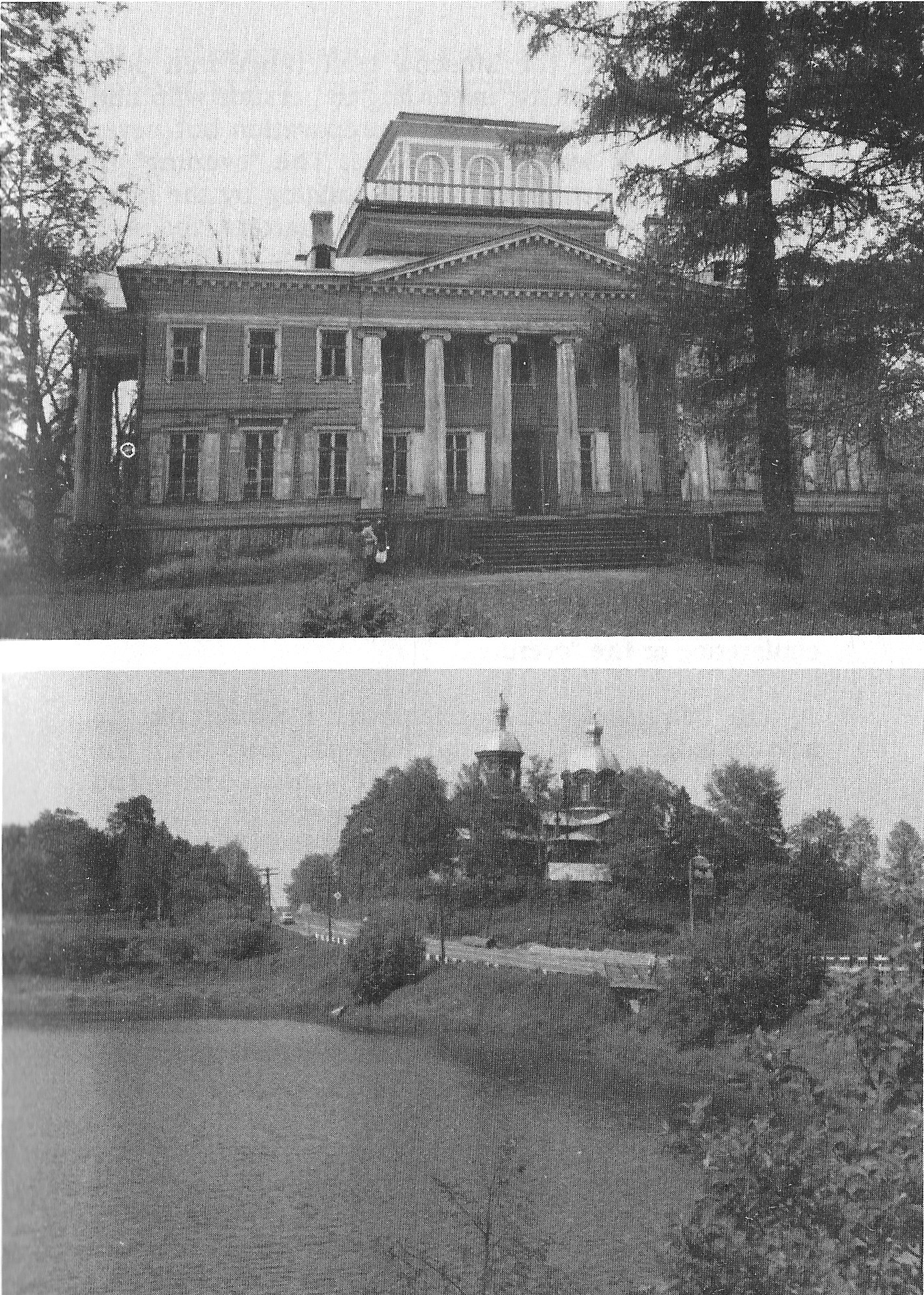

The following day, Friday, June 1 was spent visiting the locales of the three Nabokov estates about fifty miles outside of Leningrad. Nothing remains at the Vyra and Batovo sites. The sole remaining building, in poor repair, is the Rukavishnikov estate at Rozhdestveno; plans have now been drawn up for its eventual restoration. Several rooms on the ground floor house the modest beginnings of a Nabokov Museum. The exhibit consists largely of a display of family photographs, along with several graphics displaying the family tree and listing VN's works. Participants were warmly received by Valerii Melnikov, the director of the Museum and supervisor of the restoration project. He explained that they hoped to develop a literary heritage museum, giving consideration to the several literary figures prominent in the history of the region, but maintaining the central focus on Nabokov. He also explained his wish to establish a Nabokov research

[16]

center at the site. To this end he requested each of the participants to send him copies of their published work, and asked us to convey this request to all other Nabokov scholars. Books and articles can be sent to Mr. Melnikov at 188356 Leningradskaia obi., Gatchinskii r-on, s. Rozhdestveno, Istoriko-literaturnyi i memoria’nyi muzei V.V. Nabokova.

The day ended with a farewell dinner at the apartment of Mikhail Meilakh, hosted by he and his wife. About half the group then returned to Moscow on the night train; the other half remained in Leningrad. Individuals subsequently dispersed according to their separate itineraries.

The Moscow/Leningrad events provided the first opportunity for non-Russian Nabokov scholars to discover that there are a fair number of excellent scholars and a great many Nabokov enthusiasts in the USSR, as well as a good deal of Nabokov-related activity. Aside from those on the official program, mention should be made of several others who were in attendance: Evgenii Shikhovtsev, co-author of the bibliography appearing elsewhere in this issue, and a prominent Nabokov scholar; Natalia Tolstaia, Nabokov scholar and the other co-author of the bibliography; Evgenii Belodubrovsky, Alla Solov'eva, and Vladimir Kirghizov all active in Russia's newly formed Nabokov Society; Tatiana Gagen, journalist and activist, centrally concerned with the renovation of the Rozhdestveno estate and creation of the Nabokov museum. The Nabokovian, as it turned out, pledged more than a dozen new complimentary subscriptions.

There appear to be abundant plans in the USSR for the publication not only of more Nabokov works, but also translations of non-Russian Nabokov scholarship. Given the success of the conference, there

[17]

was also much talk of future conferences, the next one perhaps being hosted in Leningrad within two years. A brief item which appeared in Knizhnoe obozrenie (Book Review) on September 14 gives a good idea of the range of planned activities: "The initiating group of the [Soviet Union's] Nabokov Society has as its goals to prepare an academy-edition of Nabokov's collected works: establish a Nabokov cultural center in Moscow; publish a journal, Nabokoviana: set up a Nabokov prize for literature and award Nabokov stipends; create a Nabokov home/museum at the site of the family estates...."

_______________________________________________________________________

Photographs on the following pages

Top left

The Nabokov town house on Gertzen St. (previously Morskaya St.), Leningrad (previously St. Petersburg)

Lower left

Several of the participants: standing, left to right, Mikhail Meilakh, Leszek Engelking, Robert Alter, Vladimir Alexandrov, Alexander Dolinin, Julian Connolly, Carol Alter, the unknown but ever-present individual, David Rampton; in front, David Bethea, Sergei Davydov

Upper right

The Nabokov estate at Rozhdestveno

Lower right

The Oredezh river and the church at Rozhdestveno

[18]

[19]

[20]

In conclusion, the Moscow conference had poor local advance publicity, according to persons who had heard that a conference was in preparation but never learned that it was taking place. The "evening" in Leningrad was better publicized, judging by the large attendance. As for post-conference matters, the staff of Inostrannaia literatura sought copies of all papers delivered in Moscow, either for publication or for abstracting [this was never made clear). Copies of papers were also sought for an extensive report to be published in Russkaia mysl’ [La Pensee Russe, Paris). Several persons were interviewed for Moscow news programs; several participants were taped for a special Nabokov show being prepared for Leningrad television. A brief article describing the conference has since appeared in Literaturnaia gazeta, June 10, p. 7. Other than that, this writer is not aware of other published reports or proceedings deriving from the conference or the "evening."

On behalf of the participants I would like to acknowledge and thank the following persons: the Moscow organizers — Nikolai Anastas'ev, and particularly Natalia Izosimova who was in charge of the many daily details and complex logistics; the Leningrad organizers, Evgenii Belodubrovskii and Alexander Dolinin; Ivan Tolstoy and Mikhail Meilakh, for their exceptional hospitality to the entire group; Vladimir Alexandrov, for his service as organizer outside the USSR and official spokesman inside the USSR; David Bethea, for his yeoman's work as official and unofficial translator/ interpreter, with occasional assistance from Sergei Davydov, Alexander Dolinin, and others; Dieter Zimmer, Galya Diment, Ellen Pifer, Julian Connolly, and Vladimir Alexandrov for providing The Nabokovian with copies of their photographs; and last, but really foremost, to the individuals on the staff of Inostrannaia literatura,

[21]

all of whose names I do not know, for opening their homes and their hearts to a group of strangers.

[22]

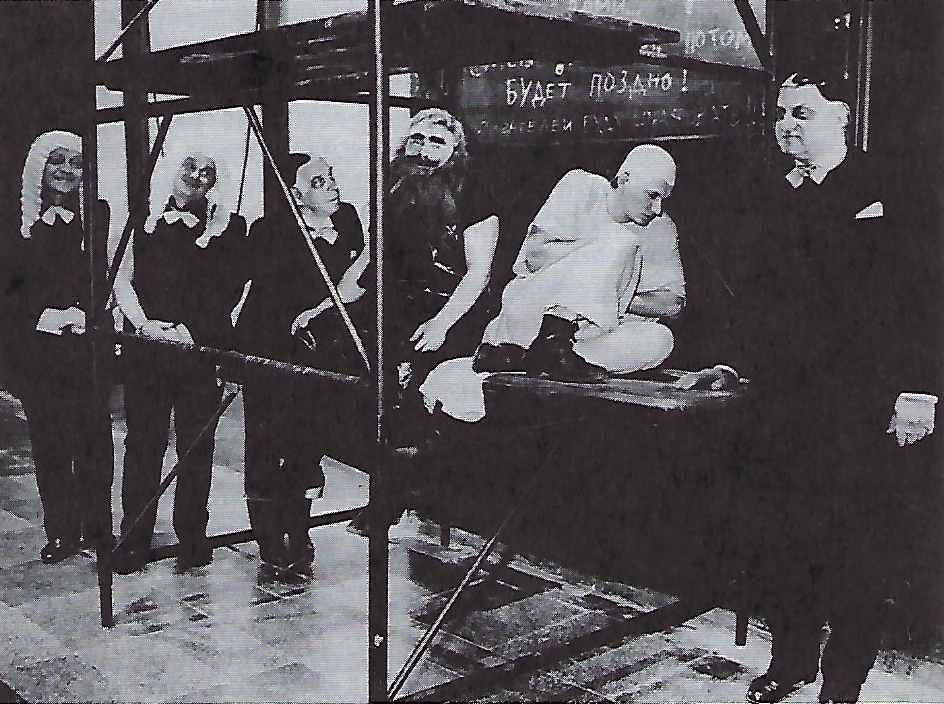

NABOKOV ON THE MOSCOW STAGE

by Brett Cooke and Alexander Grinyakin

Despite all the riches of Russia's dramatic literature, Russian theater directors have long been forced to look to Russia’s many great novels for material in order to satisfy the country's strong stage traditions. So, when Nabokov’s works began to be published in the USSR, there was little wonder that Russian audiences would not have to wait long for stagings of Nabokov's novels; by the spring of 1990 there were two such productions on the Moscow stage. Although the people involved knew little about Nabokov's reception in the West, it is interesting to note how in some instances their sensitive readings of the novels unwittingly dovetailed with interpretations long established in the scholarly literature unavailable to them.

First off the mark was the Ermolova Theater's "elite" staging (for an audience of about 100) of Invitation to a Beheading, which opened in February 1989. When Galina Bogolyubova, Associate Producing Director for the theater, first read the novel years ago, she immediately saw its potential for a stage production. She and Oleg Menshikov, one of the actors at the Ermolova Theater, only began to develop a text when it became clear that a production would be permitted. Rather than attempt to set the entire novel, they preferred to stage selected scenes from the novel: these included the opening scene with the judges and lawyers, Cincinnatus' arrival at the prison, his attempted flight with Emmie, his first meeting with M'sieur Pierre, his discussions with Pierre, visits by his wife and his mother, the meeting with the city fathers (played by women in men’s suits and derby hats), the night before the execution and execution

[23]

itself. There was little attempt to link these scenes, which were separated by darkening the entire theater.

From the very start of their project, Bogoliubova and Menshikov decided to use only material from the novel, adding no words of their own. Their sole artistic license consisted in transposing the narrator's account of Cincinnatus' thoughts from third person to first. Nabokov's widow and son both read the script and gave their approval, as they did to a videotape of the first staging.

The first production of Invitation took place on a small stage, set between two stands of spectators, facing each other. Under Valery Fokin's direction, Aleksey Levinsky played Cincinnatus. In the concluding execution scene, Levinsky would walk off the platform and, with the aid of guide-wires, float above the audience and the other characters, who stood motionless, amazed at the sight of the resurrected Cincinnatus. During the summer of 1989, however, Levinsky suffered a heart attack at this point and this production had to be abandoned.

Fokin then decided to do a different staging with another actor, Andrey Ilin, playing the role of Cincinnatus. Now the stage was placed in close confrontation with the middle of the audience, like the stem of a "T" meeting the top. The narrow proscenium was covered with citations from the novel. Claustrophobia was the prevailing mood in this rather dark production; Cincinnatus' cell consisted of a cube of pipes roughly 6' x 4' x 14'. Although he only left the cell in the concluding scene, all of the other characters constantly intruded on this metaphor for Cincinnatus' "internal world." To express his vulnerability, he wore a skull cap and a white shift, sometimes only his underwear. The style of acting emphasized both vulgarity and the absurd. Prison officials walked in

[24]

Pairs — the lawyers were handcuffed to each other — wearing similar make-up (one of them resembling the author), usually talking either in unison or repeating one another in various weird intonations. At his execution, the other characters wrap Cincinnatus in a heavy black tarp and tie it with a rope. They then watch in amazement to see Cincinnatus, who has climbed out from under the bundle unseen, appear from the side of the proscenium and silently walk around them to face the audience.

The production was much praised in the Soviet Union and tickets were very hard to find. Some spectators saw in Ilin's Cincinnatus a representation of Andrei Sakharov. The Teatr Ermolova enjoyed

[25]

even greater success with the second version in Brezzia, Italy, June 1990, playing five times before standing room only audiences and despite direct competition for one Saturday performance with the World Cup of Soccer. Italian critics called Fokin "the new Nabokov."

The SFERA Theater's staging of Lolita opened this past March. Although Ekaterina Elanskaya used a Russian translation of Edward Albee's script, she knew little about the New York production; she was completely unaware of Stanley Kubrick's film. Just the same, as in the film, a realistic portrayal of American ’’poshlost" prevailed and T. Filatova's Lolita was decidedly post-pubescent. Yury Sherstnev played both the narrator —”a certain gentleman," "a playwright and a writer (guess who?) — and Clare Quilty. On the other hand, the production was often violently expressive, especially A. Koshcheev’s rather Slavic Humbert.

The SFERA Theater is built for theater "in the round" productions. The small stage in the middle was scattered with toys, dolls and stuffed animals — a pointed reminder of the enormity of Humbert's transgression. The actors made much use of microphones set in the audience and their movements were accompanied by a stage band playing music much like that which drove the great writer to sue the Muzak Corporation of America. This production has been popular with Moscow crowds and recently sold out several performances in Kharkov.

The interest in Nabokov's novels has not been such as to cause Moscow's theaters to completely ignore his plays. The Mayakovsky Theater recently advertised their staging of ’The Event," set to open in January 1991 under the direction of Sergei Artsibashev.

[26]

V.V. NABOKOV IN THE USSR A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SOURCES: 1982-1985

by N. Artemenko-Tolstaia and E. Shikhovtsev

[The first segment of this bibliography, 1922-1975, appeared in issue #23 (Fall 1989);the second segment, 1976-1981, in issue #24 (Spring 1990). Citations are transliterated; commentaries are translated from the Russian. Our thanks to Ms. Holly Stephens for her assistance.]

1982

168. Alekseev, M.P. "Russko-angliskie literaturnye sviazi." Literaturnoe nasledstvo, t. 91. Mos: Nauka, p. 642, 847.

169. Anninskii, L. Leskovskoe ozherel’e. Mos: Kniga, p. 89.

170. Anon. "Nabokov, VI. VI." Sov. entsiklopedicheskii slovar'. Izd. 2-e. Mos: Sov. entsiklopediia, p. 851. In comparison with #129, the text is enlarged and more complimentary.

171. Apdaik, Dzh. "Budushchee romana." Pisatel'i SShA o literature, t. 2. Mos: Progress, pp. 296-298, 449.

172. Baevskii, V.S. Struktura khudozhestvennogo vremeni v EVGENII ONEGINE. Izv. AN SSSR. Ser. lit-xy i iazyka, t. 41, no. 3, p. 208, 218.

[27]

173. Baevskii, V.S. "Traditsiia 'legkoi poezii' v Evgenii Onegine." Pushkin. Issledovaniia i materialy, t. 10. Len: Nauka, p. 114, 380, 385.

174. Bashkirova, G. "Varianty sud’by.” Puti v neznaemoe. Pisatel’i rasskazivaiut o nauke. Sb. 16-i. Mos: Sov. pisatel', p. 404.

175. Bursov, B.I. Izbr. raboti v 2-kh t, t. 1. Len: Khudozhestv. literatura, p. 99. (Reprint of #94).

176. Buchis, A. "Natsional'naia samobytnost' i mirovoi kontekst." Voprosy literatury, no. 12, p. 143.

177. Vidal, G. "Amerikanskaia plastika. Znachenie prozy.” Pisateli SShA... [see #171], p. 368, 373, 449.

178. Gel'perin, IU.M. "Blok v poezii ego sovremennikov. ” Aleksandr Blok. Novye materialy i issledovaniia. Lit. Nasledstvo, t.92. Mos: Nauka, pp. 553, 584-585.

179. Gilenson, B. "Komentarii." Pisateli SShA... [see #171], pp. 434, 439, 449.

180. Dzhonston, Ch. and D. Kugul'tinov. "Dialog о Pushkine." Inostrannaia literatura, no. 1, p. 182.

181. D'iakonov, I.M. "Ob istorii zamysla Evgeniia Onegina." Pushkin...[see #173], pp. 89, 94, 380, 385.

182. (Erofeev, V.V.). "Opyt latinoamerikanskogo romana i mirovaia literatura." Latinskaia Amerika, no. 5, p. 104.

183. Zaitsev, V.N. "Omar Khaiiam i Edvard Fittsdzheral'd." Vostok-Zapad. Issledovaniia. Perevody. Publikatsiia Mos: Nauka, p. 121.

[28]

184. Zasurskii, IA. "O nekotorykh formakh ideologlcheskogo vozdeistviia na literaturu v SShA." Inostrannaia literatura, no. 8, p. 191. (Reprinted in #200, #222).

185. Zverev, A. "K voprosu ob amerikanskom postmodenizme." Inostrannaia literatura, no. 6, p. 202.

185a. Koreneva, M.M. "Golos avtora-golos deistvitel'nosti." Novye khudozhestvennye tendentsii v razvitii realizma na Zapade. 70-e gody. Mos: Nauka, pp. 258,318.

185b. Kugul’tinov D. and Ch. Dzhonston. "Dialog o Pushkine.” Teegin gerl/Svet v stepi/Elista. Kalmytzkaia ASSR no. 1, p. 90. (An expanded and changed version of #180.

186. Mikhailov, O. Stranitsy russkogo realizma. Zametki о russkoi literature XX veka. Mos: Sovremennik, pp. 133-134. (Reprint of #66 with changes and abridgements.)

187. Muliarchik, A. "Sud'by 'literaturnogo isteblishmenta' v SShA." Inostrannaia literatura, no. 5, p. 208. (Reprinted in #238, p. 20).

188. Onetti, Kh.K. "Po vine Fantomasa." Pisateli Latinskoi Ameriki o literature. Mos: Raduga, p. 329, 389, 395.

189. Petrushevskaia, L. "Smotrovaia ploshchadka" [rasskaz], Druzhba narodov, no. 1, p. 58. (The usage of the name Lolita as a common noun).

190. Rait-Kovaleva R Chelovek iz Muzeia Cheloveka. Povest’ o Borise Vil'de. Mos: Sov. pisatel', pp. 233-234.

[29]

190a. Reiser, S.A. Russkaia paleografiia novogo vremeni. Neogrqfiia. (Uchebnoe posobie dlia studentov vuzov spets. "Istoriia"). Mos: Vyshaia shkola, p. 75.

191. (Sokolov, M.N.) "Nasekomye." Mify narodov mira. Entsiklopediia v 2-kh t. t. 2. Mos: Sov. entsiklopediia, p. 203.

192. Sokhriakov, IU.I. "Vospriiatie tvorchestva N.V. Gogolia v SShA.” Filologicheskie nauki, no. 4, pp. 25, 26, 28-29, 31, 32.

193. Kharitonov, V. "Izbrannaia bibliografiia." L'iuis Kerrol i ego mir. Mos: Raduga, p. 142.

194. Johnston, Ch. and D. Kugultinov. 'Talking About Pushkin." Soviet Literature, no. 2, p. 171. (Same as #180).

1983

194a. Andzhaparidze, G. "Sovremennyi angliskii roman." Sost. M. Bredburi i D. Palmer. Sovremennaia khudozhestvennaia literatura za rubezhom. Inf. sbomik, no. 2, 158, p. 24.

195. Baevskii, V.S. "Vremia v Evgenii Onegine." Pushkin. Issledovanniia i materialy, t. 11. Len: Nauka, pp. 115, 117, 119-121, 123-124,352, 356.

196. Berdnikov, G. "Tvorcheskoe nasledie Gogolia." Znamia, no. 10, p. 211. (Reprinted in #231)

196a. Braginskii, A. '"Nashivki slavy' Dzhein Birkin." Kino (Riga), no. 8, p. 28. [The use of Lolita and "nimfetochka" as common nouns).

[30]

197. Brill, T. Vozdeistvie na proizvedeniia iskusstva. Mos: Mir, p. 7. [Epigraph from Nabokov]

198. Voznesenskii, A. Sobr. soch. v 3-kh t., t.l. Mos: Khudozhestv. literatura, p. 81. [reprint of #132].

199. Evtushenko, E. Voina - eto antikultura. Mos: Sov. Rossiia, p. 70. [reprint of #158]

200. Zasurskii, IA.N. "Izuchenie amerikanskoi zhurnalistiki i literatury v usloviiakh sovremennoi idieologicheskoi bor'by." Problemy amerikanistiki, 2. Mos: Izd. Mosk. gos. un-ta, p. 312. [Reprint of #184 with changes]

201. Korotich, V. Litso nenavisti Roman v pis'makh. Oktiab’, no. 7, p. 97. [see #202, #224a, #235]

202. Korotich, V. Litso nenavisti Roman v pis'makh. Mos: Pravda, p. 181. [reprint of #201]

203. Kuznetsov, F. Nigilisti? D.I. Pisarev i zhurnal "Russkoe Slovo." 2-e izd. Mos: Khudozhestv. literatura, p. 5. [reprint of #148].

204. Likhachev, D.S. Tekstologiia. Na materiali russkoi literatury X-XVE vekov, 2-e izd. Len: Nauka, p. 541.

205. Lotman, IU.M. Roman...see #149. 2-e izd. Len: Prosveshchenie. [photocopy of #149]

205a. M.P. "Posviashchaetsia Gogoliu." Voprosy literatury, no. 12, p. 267. [Nabokov is mentioned in the speech by G. Berdnikov, "The Socio-Historical and Common in the Works of N.V. Gogol," at the Third Soviet-Japanese literary scholarship symposium in Tokyo.]

[31]

206. Mendel’son, M. Roman SShA segodnia-na zare 80-kh godov. izd. 2-e. Mos: Sov. pisatel', pp. 31, 241-242. [reprint of #104]

207. Muliarchik, A.S. "Konformizm i literatura 50-kh godov." Problemy amerikanistiki... [see #200], pp. 324-327. [reprint of #96 with changes and additions]

208. Semenov, IU. Litsom k litsu. Mos: Politizdat, p.184.

209. Skachkova, O.N. "Temy i motivy liriki A.S. Pushkina 1820-kh godov v Evgenii Onegine." Boldinskie chteniia. Gor'kii: Volgo—Viatskoe knizhnoe izd., p. 47.

209a. Tvardovskii, A. ”Iz pisem о literature." Voprosy literatury, no. 10, p. 207. [reprinted with additions to the footnotes in #210, #241]

210. Tvardovskii, A. Sobr. soch. v 6-ti t., t. 6. Mos: Khudozhestv. literatura, p. 254, 567, 656.

211. Time G.A. i P. IU. Danilevskii. "Novyi perevod Evgeniia Onegina na nemetskii iazyk." Vremennik Pushkinskoi komissii 1980. Len: Nauka, 1983, p. 159.

212. Feinberg, I.L. Abram Petrovich Gannibal - pradel Pushkina. Razyskaniia i materialy. Mos: Nauka, pp. 23-24, 40, 46-48. [reprint of #166 with insignificant changes]

213. Chupinin, S. "Andrei Voznesenskii: logika alogizma." Krupnym planom. Poeziia nashikh dnei: problemy i kharakteristiki. Mos: Sov. pisatel', p. 172. [reprint of #98a]

[32]

214? It is said that in the summer of 1983, the journal Kino, which is published in Riga in Russian and Latvian, mentioned the film, "Lolita."

1984

214a. Anastas'ev, N. Obnovlenie traditsii Realizm XX veka v protivoborstve s modemizmom. Mos: Sov. pisatel', p. 59.

215. Arapov, M. "Skol'ko slov v iazyke? ili Kratkoe opisanie lingvisticheskogo opyta, prodolzhit' kotoryi avtor priglashaet chitatelia." Znanie -sila, no. 2, p. 25.

216. Brink, A. "Na raznye golosa." Inostrannaia literatura, no. 3, p. 188.

216a. Voznesenskii, A. Iverskii svet Stikhi I poemy. Tbilisi: Merani, p. 14. [reprint of #132, p. 170 and #58]

217. Voznesenskii, A. Sobr. soch. v 3-kh t, t.2. Mos: Khudozhestv. literatura, p. 69. [reprint of #58]

218. Gal'tseva, R, IA. Rodnianskaia i V. Bibikhin. '"Obeskurazhivaiushchaia figura' (N.V. Gogol v zerkale zapadnoi slavistiki)." Voprosy literatury, no. 3, pp. 127, 132, 138-140, 149, 152. [reprinted in #232]

219. Granin, D. "Eto bylo pri nas..." [interview with L. Lazarevym], Voprosy literatury, no. 9, p. 129.

220. Dubin, B. "Kommentarii." Borkhes KH. L. Proza raznykh let Mos: Raduga, p. 291.

221. Evtushenko, E. Sobr. soch. v 3-kh t., t. 2. Mos: Khudozhestv. literatura, p. 482. [reprint of #59]

222. Zasurskii, IA.N. Amerikanskaia literatura XX veka. Izd. 2-e. Mos: Izd. Mosk. gos. un-ta; pp. 485, 498. [reprint of #184]

223. Kataev, V.P. Sobr. soch. v 10-ty t, t. 6. Mos: Khudozhestv. literatura, p. 498. [reprint of #45]

224. Kataev, V.P. Sobr. soch...[see #223], t. 7, p. 151. [reprint of #116].

224a. Korotich, V. Nenavist. Roman v pis'makh. Mos: Khudozhestv. literatura, Roman-gazeta #20, p. 58. [reprint of #201]

225. Melen'tev, IU. "Almaz istiny i ugol' izmyshlenii." (Nasledie N.G. Chernyshevskogo i nekotorye voprosy sovremennoi ideologicheskoi bor'by). V mire otechestvennoi klassiki. Mos: Khudozhestv. literatura, p. 86. [reprint of #120 with changes]

225a. Myrav'ev, V.S. "William Golding. Bumazhnye liudishki." Sovremennaia khudozhestvennaia literatura za rubezhom. 167, no. 5, pp. 21-22.

226. Saitanov, V. "Pervyi sovetsko-amerikanskii simpozium po pushkinistike." Voprosy literatury, no. 10, p. 277. [Clear suggestion that V. Soloukhin, at the symposium on June 6, 1984, called for the popularization of VN's Eugene Onegin].

227. Khrapchenko, M.B. Niklai Gogol. Literaturnyi put'. Velichie pisatelia. Mos: Sovremennik, pp. 621, 623-625, 627, 649. [reprint of #154]

228. Chagin, A. "Poety i politikany." Lit gazeta, no. 30, 25 Iunia, p. 2.

[34]

1985

229. Anastas'ev, N. "Preodolenie Ulissa." Voprosy literatury, no. 11, p. 160.

229a. [Anon.] "Iz kommentariia k Evgeniiu Oneginu. Vremennik Pushkinskoi komissii, 1981. Len: Nauka, 1985, p. 159. [see #240, #244a]

230. Baranova-Gonchenko, L. "Lovtsy zhemchuga, pokhutiteli velosipedov...l o vysokom." Lit ucheba, no. 4, p. 131.

231. Berdnikov, G.P. Nad stranitsami russkoi klassiki Mos: Sovremennik, p. 49 [reprint of #196]

232. Bibikhin, V.V., R.A. Gal’tseva, i Rodnianskaia. "Literaturnaia mysl’ Zapada pered 'zagadkoi Gogolia’." Gogol istoriia i sovremennost‘. Mos: Sov. Rossiia, pp. 391, 397-398, 404-406, 408, 422-423. [reprint of #218 with insignificant changes]

233. Voznesenskii, A. Mat. Studentcheskii meridian, no. 9, p. 33. [reprint of #132]

234. Vosnesenskii, A. "Saga o sapogakh." Oktiabr', no. 10, pp. 89-90.

234a. Gubin, A. "Zhestokii miatezh." Afina Pallada Iz knigi poetov. Stavropol'skoe knizhnoe izd-vo, p. 299.

234b. Denisova, T.N. Ekztstentsialism i sovremennyi amerikanskii roman. Kiev: Naukova dumka, pp. 221, 243.

235. Korotich, V. Litso nenavisti Roman v pis'makht publitsistika. Mos: Sov. pisatel', p. 226. [reprint of #201]

[35]

235a. Mar'ianov, B.M. Krushenie legendy. Protiv klerikal'nykh fal'sifikatsii tvorchesta A.S. Pushkina. Len: Lenizdat, p. 84.

236. Molotkov, G. i L. Orlov. "Tlkhle diversanty. Dokumental'nyi ocherk." Zvezda, no. 3, p. 176.

237. Muliarchik, A.S. "Realizm v poslevoennom romane SShA." Problemy amerikanistiki. 3. Mos: Izd. Mosk. gos. un-ta, p. 263. [reprinted in #238, p. 12]

238. Muliarchik, A.S. Spor idet o cheloveke. O literature SShA vtoroi poloviny XX veka. Mos: Sov. pisatel’, pp. 12, 20, 29, 35, 67-69, 93, 355. [reprinted with changes and additions in #96, #187, #207, #238]

238a. Oleneva, V.I. Modernistskaia novella SShA. 60-70-e gody. Kiev: Naukova dumka, pp. 107-108, 111, 121, 136, 138, 139, 208.

239. Stepanov, V.G. "Kritika otsenki povestei N.V. Gogolia burzhuaznym literaturovedeniem Anglii i SShA 40-kh - 60-kh godov XX veka: I. Perri, V. Nabokov, B. Erlich." Funktsional'noe i sistemno-tipologicheskoe izuchenie iazyka i literatury. Mos: 1984, pp. 206-213. Rukopis' deponir. v INION AN SSSR No. 18858 ot 29/11/84. Zaregistrir: Novaia sovetskaia literatura po obshchestvennym naukam. Literaturovedenie. Bibliografich. ukazatel', 1985, no. 7, p. 85.

240. Stepanov, V.P. "Iz kommentariia k Evgeniiu Oneginu." Vremennik Pushkinskoi komissii. 1961. Len: Nauka, 1985, p. 160.

240a. Suslova, A.V. i A.B. Superanskaia. O russkykh imenatkh. Len: Lenizdat, pp. 146, 149.

[36]

241. Tvardovskii, A.T. Pis'ma o literature. 1930-1970. Mos: Sov. pisatel’, pp. 319, 470, 494. [reprint of #209a with insignificant changes]

242. Terterian, I. "Khulio Kortasar: igra vzapravdu." Kortasar, KH. 62. Model' dlia sborki. Mos: Raduga, p. 7.

243. Feinberg, I. Chitaia tetradi Pushkina. Mos: Sov. pisatel', pp. 424, 450, 456-457. [reprint of #212]

244. Folkner, U. Beseda v Vest-Pointe, 20/4/62. Stati rechi interv'iu, pis'ma. Mos: Raduga, pp. 385-386, 471, 482.

244a. Fomichev, S.A. "Iz kommentariia k Evgeniiu Oneginu." 6. Vremennik...[see #229a], p. 167.

245. At the end of the 70s and in the 80s, in Moscow and several other cities in the USSR, E. Evtushenko's photo exhibits were repeatedly organized, and they included a series under the title "Lolita."

246. In the 80s a documentary, directed by V.B. Vinogradov, was shown several times on Leningrad television. "Elegy," the documentary, was dedicated to the places where Nabokov spent his childhood. Family photographs of the Nabokovs were included in the film, but without any sort of reference to their name. In the fall of 1986 the film was shown on national television.

[37]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

[Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov’s works will be to the most recent hardcover U.S. editions.]

DONT RIDE BY, RE-READER

In Nabokovian 23, Pekka Tammi drew attention to Turgenev's phrase "Mimo, chitatel', mimo," quoted in both "Lips to Lips" and Ada, and translated in the latter as "Ride by, reader, ride by." The source for this allusion, however, is found not in A Sportsman's Sketches, as Tammi, citing Leszek Engelking, erroneously suggested, but in Smoke [Dym), which seems to have been one of Nabokov's favorite targets when he chose to mock at Turgenev (for example, it is twice ironically alluded to in The Gift). After telling a rather vague and elliptical story of a seduction, adultery and suicide, the narrator of Smoke writes: "Strashnaia temnaia istoria. . . . Mimo, chitatel', mimo" (Sochinenia v 15-ti tomakh [Moscow-Leningrad, 1965] 9: 280). Translation: "A terrible, dark story. . . . Pass by, reader, pass by.” What Turgenev means here by mimo is absolutely clear: the morbid story he has just outlined is so unpleasant and depressing that it would be better for readers to pass

[38]

over, skip, not probe deeper. Therefore it is not only dull Ilya Borisovich from "Lips to Lips" but also the over-inventive narrator of Ada who misinterprets Turgenev by translating his mimo as "ride by." This intentional distortion of the original produces a typical Nabokovian effect—a play on the alliteration of "read” and "ride," which makes these two verbs semantically related. Thus, the change in the phrase and the introduction of the additional allusion to Yeats in the French translation of Ada mentioned by Tammi were most likely intended to serve as a partial compensation for the loss of this phonetic interplay (cavalier-Tourgueniev-Yeats), and a means to maintain a connection between "reading" and "riding" ("cavalier" anagrammatically contains "lire" and "livre").

The direct allusion to Turgenev's phrase in Ada, however, should not be viewed as a casual aside and deserves further consideration. As is often the case with Nabokov’s allusions, it triggers a chain reaction of complementary associations and points to a cluster of Turgenev’s motifs, images and names hidden in the nearby context. The very tour of Ardis Hall brings to mind numerous descriptions of country estates in Turgenev novels and tales: "A yellow drawing room hung with damask" which "opened in the garden" (42) seems to mimic similar rooms in A Nest of Gentlefolk, Fathers and Sons, or Virgin Soil; "the music room with its little-used piano” (43) hints at Turgenev's overused "night and music” theme which Nabokov alluded to in Lectures on Russian Literature (65, 85) and in Lolita (cf.: "As in a Turgenev story, a torrent of Italian music came from an open window," 290: Alfred Appel was not able to identify the correct source of this allusion—a fantastic story "Ghosts" [Prizraki] where the hero finds himself in Rome and listens to the sounds of an Italian aria coming from an open window of a palace [Sochinenia 9: 92-93]; at the same time the

[39]

word torrent implies another Turgenev story with the Italian setting, 'Torrents of Spring"); the Gun Room (43) evokes Turgenev's hunting theme, and a "stuffed Shetland pony which an aunt of Van Veen’s, maiden name forgotten . . . once rode” (43)—well-known Turgenev amazons, seductive, alluring, sexy women who destroy happy engagements and marriages. It is worth noting that one of the most famous among these riding temptresses, Countess Irina Osinina from Smoke, is the namesake of Dan Veen's aunt. Countess Irina Garina whose second name, forgotten by Ada but not by the author, is semantically related to the title of the Turgenev novel (Russian gar' means cinder or any other product of burning). In fact, all the other Russian names in the passage under discussion have an aura of Turgenevesque associations: in A Nest of Gentlefolk we meet another Anna Pavlovna, the hero’s grandmother, and the nickname Paul-minus-Peter could be explained as an ironic transformation of Uncle Pavel Petrovich in Fathers and Sons. Even the Russian equivalent of "wallflower" — zheltofiol' — takes its literary origin in A Nest of Gentlefolk, where the rare word is used to prove the botanic erudition of the heroine (Sochinenia 7: 242).

I'm quite sure that all these examples are rather loose and could be easily written off as pure conjecture. But still, they illustrate an important point often missed by zealous Nabokov subtext-hunters, who tend to simplify the intricate semiotic machinery of his allusive games—namely, the retroactive effect of an explicit allusion. More often than not, a cited name of a writer, a given title or an open quotation sends us back to the preceding part of the Nabokov text and thereby generates a layer of collateral significations in it. In other words, it introduces a new code for rereading which activates implicit associations with the corpus of the cited writer's works—not only with a single isolated subtext but with his style in general.

[40]

with his Idiosyncratic themes, details and characters, with his vision of the world. When Nabokov quotes the phrase from Smoke, it serves as a signal for the re-reader not to "ride by" such a layer of potential Turgenev parallels which, if revealed, would add a certain flavor to the multilevel and multilingual discourse of Ada.

—Alexander Dolinin, Pushkinskii Dom, Academy of Sciences, Leningrad

NABOKOV’S BORROWED TRAMPOLINE

In his perceptive review essay of Nabokov’s early novels and stories in Russian (1930), Nikolay Andreyev wrote of The Defense, the most recent novel, that "this extremely complex story turns out to be simply a trampoline enabling Sirin to make a brilliant leap into breathtaking expanses of art and deep secrets of human psychology" (Nov' 3 [1930], trans. Andrew Field as "Nikolay Andreyev on Vladimir Sirin [Nabokov]," rpt. in Critical Essays on Vladimir Nabokov, ed. Phyllis Roth 53). A decade later, Nabokov used a similar figure to describe the narrative strategies of his fictional writer Sebastian Knight:

he used parody as a kind of springboard for leaping into the highest region of serious emotion. J. L. Coleman has called it "a clown developing wings, an angel mimicking a tumbler pigeon," and the metaphor seems to me very apt. Based cunningly on a parody of certain tricks of the literary trade, The Prismatic Bezel soars skyward. (RLSK 91)

[41]

Several elements in this passage suggest that unlike Sebastian (39), Nabokov collected his reviews or at least read Andreyev's: the parallel imagery (the text as a springboard used in tumbling, which propels the writer into faraway regions); the attribution of the metaphor to someone else (the presumably fictional "J. L. Coleman"); and the emphasis on parodying "certain tricks of the literary trade."

It would be fitting, too, for Nabokov to describe Sebastian Knight's narrative technique with a figure borrowed from one of his own Russian critics. The Real Life of Sebastian Knight was the first novel that Nabokov composed in English, and the first published under his own name; as several critics have pointed out, the ambiguous doubling of Sebastian and his Russian half-brother seems to reflect Nabokov’s own bilingual literary career. Accordingly, Nabokov may have appropriated this evocative image from a Russian review of V. Sirin's oeuvre, translated it into English, attributed it to a fictitious Englishman, and woven it into his novel, in order to ironically acknowledge the relationship between Sirin and himself—just as, in Speak, Memory, he playfully refers to Sirin (and émigré critics' "acute and rather morbid interest in his work") only in the third person (287-88).

—S. E. Sweeney, College of the Holy Cross

HOW NOT TO READ ZEMBLAN

In the fourth chapter ("Language: Anglo-Saxon") of her recent book on Pale Fire (Find What the Sailor Has Hidden, 1988), Priscilla Meyer proposes etymologies for a number of Zemblan words and names. An earlier

[42]

version, "Etymology and Heraldry: Nabokov's Zemblan Translations (A bot on the Nabokov Escutcheon)," appeared in Texas Studies in Literature and Language 29 (1987): 432-41; in the following discussion page numbers refer to the book version.

Compared to earlier treatments of Zemblan (John R. Krueger, "Nabokov's Zemblan: A Constructed Language of Fiction," Linguistics 31 [1967]: 44-49; Ronald E. Peterson, "Zemblan: Nabokov's Phony Scandinavian Language," VNRN 12: 29-37) which refrained from investigating the function of that invented language, Meyer's is far more ambitious: "The etymologies of several Zemblan words discover themes important both to Pale Fire and to Nabokov's life" (88). She claims that the "Anglo-Saxon" roots of Zemblan carry hidden meanings concealed by modern Germanic surfaces (88). Unfortunately, Meyer's discussions are a travesty of serious scholarship. A foretaste of what is to come is given by her handling of harvalda, "the heraldic one" (89). Meyer turns to a dictionary and finds "that the word heraldry derives from Anglo-Saxon: har, "the highest, glorious," plus valda, "to rule over, to be the cause of." I do not know what kind of dictionary Meyer used but any modem desk dictionary would tell her that heraldry is derived from herald which in turn goes back to Old French (or Middle French) and ultimately to continental Germanic. The unabridged Merriam- Webster, 2nd. ed., gives hari, heri, "army," and waltan, "to manage, govern" as sources. The "Anglo-Saxon" words quoted by Meyer do not exist; apparently she has not consulted a dictionary of Old English (under which name the language is known nowadays). There are, of course. Old English w(e)aldan, "to rule," and Old Norse valda (in spite of the title of her chapter Meyer keeps confusing the two languages). Whether Kinbote and, by implication, Nabokov used an Old English dictionary is extremely doubtful. One does not have to be an

[43]

Anglo-Saxonist to discover that a cat-and-mouse game is going on in muscat (89). Equally I fail to see why the obsolete past tense rad of read should direct the reader to Anglo-Saxon any more than the regular past (89). Instead of reading preconceived ideas into Zemblan words Meyer should have turned to a "Bible-like Webster" and "a stolid grown-up" encyclopedia (Pale Fire 166, 83). Webster's is an especially rich source of Zemblan vocabulary (and then there are several European languages).

I proceed to discuss Meyer's etymologies (90-98) one by one. Special attention is paid to the "Anglo-Saxon" components.

The Kongs-skugg-sio

This is neither Zemblan nor Anglo-Saxon, so does not properly belong in this chapter. Kinbote only claims that Hodinski collected Zemblan variants to the Old Norse speculum regale (Pale Fire 76). In Meyer’s discussion the ghost of Nabokov's father makes his appearance.

grad

There is no Anglo-Saxon grada as claimed by Meyer, but there is an Old Norse gráda. The Old English equivalent would be grad(e). Both derive from Latin gradus (as does German Grad). Nothing is gained by bringing the "Anglo-Saxon" and Old Norse forms into play.

sampel

Meyer splits the bird-name into sam and pel. The second element is claimed to be derived from Anglo-Saxon paell, "pall, purple," and a

[44]

quotation from Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica is adduced. The latter is garbled (for confictur read -ficitur) and mistranslated (Bede, Incidentally, is speaking of whelks). Meyer is not sure about what the first element is to represent: Latin semi, "half," or the Slavic

sam, "oneself, lonely"? She fails to take into account the useful translation provided by Kinbote: a sampel is supposed to be a bird called "silktail" (Pale Fire 73). When one looks for "silktail" in an unabridged dictionary of English one discovers that there is indeed a silk-tail, another (dialectal) word for the waxwing. In the Linnaean classification the waxwing is called Ampelis garrulus (cf. older and better editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica). I submit that sampel goes back to ampelis. So after all, Kinbote "sam” has not "assumed the paell “(93). (Note for future Pale Fire exegetes: cf. Russian sam pel!)

narstran

Another of Meyer’s howlers is her treatment of narstran, "a hellish hall where the souls of murderers were tortured under a constant drizzle of drake venom coming down from the foggy vault" [Pale Fire 213). Narstran has nothing to do with Slavic strana or with Valhalla, which is quite a desirable place for any Germanic warrior and not the dismal dungeon suggested by Kinbote's definition. A search in the unabridged Webster's yields the following:

Na'strond#..., Na'strönd#..., n. ON. naströnd, fr. nar corpse + strönd (gen. strandar) strand, shore. Norse myth. A dank, venom-dripping hall, in

[45]

Niflheim, the place of future punishment of murderers and perjurers.

Grindelwod

The Zemblan place-name is connected by Meyer with Nabokov’s spurious yam of an ape who drew a picture of the bars of his cage (cf. his afterword to Lolita). The components of Grindelwod as suggested by Meyer are Anglo-Saxon grindel "bar, bolt, pl. iron grating," and wod, "mad." A simpler and far more likely derivation is from the Swiss place-name Grindelwald. Grindelwod is mentioned together with Aros (Pale Fire 138) which is derived from Arosa, another Swiss resort.

shargar

Meyer's etymology of shargar is as a compound of Anglo-Saxon and Old Icelandic sar, "pain, wound, grief," and gar, 'javelin, spear." She is unable to see that the word in hand starts with a /s/ sound and not with an /s/. The Bible-like Webster has an entry shar'gar explained as "a lean, faded, or stunted person or animal; a starveling. Scot." This is not too far removed from Kinbote's definition ("puny ghost"). (A non-rhotic pronunciation of shargar may call forth associations of Russian sag, "step," and its inflected forms—one more permutation of Gradus.)

Radugavitra

One should by all means stop where normally, according to Meyer, the reader does when he takes the name as a compound of Russian

[46]

raduga, "rainbow," and English vitreous, "glassy" (or Latin vitrum, "glass"). The rest of Meyer's note is pure speculation.

Kinbote's name is linked by Meyer with the Old English hapax legomenon sar-bot, "compensation for a wound." As demonstrated s.v. shargar there is no sar, so there is no sar-bot either. The most lucid discussion so far is the one by D. Barton Johnson, Worlds in Regression 68-73. I will return to the name below.

raghdirst

This compound is clearly derived from German Rach(e)durst, "thirst for revenge." Ragh- (with a voiced velar fricative) is certainly not related to English rage or Latin rabies. Under raghdirst Meyer also mentions wodnaggen, "a white-and-black, half-timbered house." Just as there is not an Anglo-Saxon wod, "mad," concealed in Grindelwod, there is not one in wodnaggen (wod = wood I do not see where Old English gnagan, "to gnaw," comes in. I am by no means sure from where naggen is derived, but hesitantly suggest English nogging, "rough brick masonry used to fill in the open spaces of a wooden frame." The further discussion of bogtur is funny beyond words.

velkam ut Semblerland

"Ufgut, ufgut, velkam ut Semblerland!" goes back to Swedish "Adjö, adjö, välkommen till Sverige!" (New York Times 20 July 1959; cf. Beverly Lyon Clark, Reflections of Fantasy:

[47]

The Mirror-Worlds of Carroll, Nabokov, and Pynchon 80). Why Nabokov chose to translate till as ut is a crux that has yet to be solved by Zemblan philology. The claim that ut is Anglo-Saxon "out" seems to be far-fetched after all. It could be Swedish, for instance.

As I hope to have shown, there is no need to credit Kinbote (or Nabokov) with any deep-going "Anglo-Saxon" expertise. Meyer's etymologies are spurious (and sometimes hilarious). She fails to present any solid evidence for the notion of "compensation for a murdered relative”: "The Anglo-Saxon etymologies that Nabokov has hidden in Kinbote's Zemblan coinages show that Pale Fire is a remedy for Nabokov too, a recompense for a murdered relative" (i.e. his father) (98). The ’’Anglo-Saxon” etymologies do not show anything, but again a possible clue is hidden in Webster's (and Meyer might have spared her readers the whole chapter if she had consulted it). Compare the dictionary s.v. kinbote (for what it is worth):

kinbote’..., kin'bot’..., kin'boot'..., n. Old Law. Bote given by a homicide to the kin of his victim.

In addition the definition given in the Oxford English Dictionary should be considered (s.v. kinboot): "A wergeld or man-boot paid by a homicide to the kin of the person slain. (Not the same as the O.E. cynebót or royal compensation.)" I still fail to see the ghost of Nabokov's father, and it appears that Meyer's etymologies are but a simplistic attempt at linking Nabokov's biography with the world of Pale Fire. As one researcher into the Zemblan language put it: "we must be extremely careful in our analysis of this fanciful and now extinct language" (Peterson 37).

—Manfred Voss, Cologne, Federal Republic of Germany

[48]

IN REPLY

I am grateful to Mr. Voss for pointing out an error in my chapter on etymology, har and valda are indeed Old Norse and not Anglo-Saxon. But Mr. Voss and I do not disagree—waltan, w(e)aldan, and valda are different places on the same elephant—that is, closely related forms of the same word used at the same period in the same geographical area. My book contends that Pale Fire represents a synthesis of Nabokov's Russian with his Anglo-American tradition; the term "Anglo-Saxon" has cultural as well as linguistic connotations and I use it as much to denote a period as a language, as is, I hope, clear in the context of my book. It would be a shame were Joseph Bosworth's An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon, 1848) cited in my bibliography to be disqualified by Mr. Voss for the archaic usage of Anglo-Saxon to connote Old English.

Let us remember that the Zemblan language does not exist (though it is spawning myriad experts). And that Nabokov is having fun with Kinbote's "spurious and hilarious" derivations (as Mr. Voss begins to do with his ingenious Russian source for sampel, one which I note echoes but does not address my speculations). I trace possible meanings of Zemblan words in Anglo-Saxon, Old Norse and Old Icelandic roots on the one hand, and in Slavic on the other, finding associations with Nabokov’s thematic concerns hidden behind Kinbote's ostensible etymologies. Certainly I should have mentioned Old Norse Nastrond in the derivation of the Zemblan Narstran. But here is the crux of our disagreement: Mr. Voss and I agree that Nar means "corpse," but he finds the Slavic strana (aptly) a "howler." That Nabokov has

[49]

changed "strond" to stran in Zemblan suggests to me (and naturally this is only speculation) that he wanted the word to permit of both Old Norse and Slavic roots. The ideas of "strand” and "strana" are close enough to allow this deliberate conflation. Thus neither Kinbote's nor Nabokov's etymologies represent some fixed etymological truth, but rather point to a theme that runs through the Zemblan vocabulary. This theme is epitomized by the word bot. I do not see that Mr. Voss and I differ in our definition of bot as "bote given by a homicide to the kin of his victim" (Voss) and "recompense for a murdered relative" (Meyer). D. B. Johnson does indeed discuss Kinbote's name and its relation to Botkin (cited in my book); he does not however essay any possible etymology of the name. Johnson and I both naturally discuss the connection to Hamlet's dagger. My book treats Kroneberg's translation of Hamlet (edited by V. Botkin), and the potential (but unprovable absolutely) source of the novel's title in King Hamlet's ghost's parting words to his son ("the glowworm . . . 'gins to pale his ineffectual fire," I,v), further links in an extensive chain of evidence of Nabokov's theme of revenge for a murdered father. But Mr. Voss discusses the etymologies in isolation from the context of my book (where "solid" evidence may be found).

Since Mr. Voss accepts at least "the strand of the corpse" and the concept of wergeld (derived from AS wer, "man," and ME gelden, "to castrate"), I fail to see why he fails to find the shadow of a ghost in Pale Fire.

—Priscilla Meyer, Wesleyan University

[50]

VLADIMIR D. NABOKOV AND CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

by Gennady Barabtarlo

Many have said that Nabokov's special revulsion toward murder and execution, various types of which are staged and studied in so many of his novels, owes much to his father's views on the matter and to his terrible and valiant death — which is a flashing and engirding theme in Speak, Memory.

V. D. Nabokov was a lifelong opponent of capital punishment and railed against it fiercely both as a jurist writing on legal matters and as a member of the Russian parliament. His first published work on the subject, "Proekt ugolovnago ulozheniia i smertnaia kazn'" (A Draft of the Penal Code and the Death Penalty, "Pravo", 30 Jan. 1900, pp. 257-63), he ends by applying words from an early Alexander I’s edict banning the practice of torture, to capital punishment (he invokes them again in the essay printed below); He says that, just as torture, murder by law must be abolished "so that eventually the very term, which inflicts shame and reproach upon mankind, may be forever blotted out from the [Russian] people’s memory.’’

In the First State Duma (1906), Nabokov was in the center of the debate on the death penalty that began on May 18th, and made a famous speech on June 19th, the day when the Duma was to vote on the abolition of capital punishment. VDN's speech was a response to the weak argumentation for preserving the death penalty for political terrorists that was put forward by

[51]

Shcheglovitov, Minister of Justice. Here is an excerpt from the speech, in my translation:

"As early as the 1880s, the editorial committee in charge of the Penal Code Bill, consisting as it did of the foremost authorities in criminal law science, issued a unanimous opinion that 'Russia could take a new and further <sic> step along the historic path charted even during the reign of Elisabeth, and not only limit as much as possible instances of the death penalty application but strike it altogether out from the list of penalties inflicted under common law.’ The committee had arrived at this conclusion upon analysing all the arguments adduced in favor of preserving capital punishment and after seeing their total groundlessness.

"The events of our time show convincingly what enormous danger lurks in the government’s preserving the death penalty, even as an extraordinary measure. Although its very notion suggests an extreme form of punishment applied in rare cases and with the observance of all the guarantees of due judicial process, in reality the death penalty quite easily degenerates into mass murder that can have no justification either from the moral or social standpoint; that strikes a huge number of victims, whose guilt often has not been established with satisfactory precision; that enrages the entire society, and brings forth new crimes. Faith in the significance of the death penalty as a deterrent has been completely lost. It remains in our laws only as vestige of the old barbarity.

"Having chosen the path of renewal, Russia must immediately, once and for all, break with that heritage of cruel and gory times. She must join the countries that have admitted that punishment by

[52]

death is incompatible with a certain level of moral evolution of the nation. The State Duma has already spoken unanimously in favor of the abolition of capital punishment; now it ought to effect an official realization of this recommendation." [In VDN's report "The Bill of the Abolition of Capital Punishment", in the collection The First State Duma (Second Issue, "Legislative Activity"), published by VDN and A.A. Mukhanov (St. Petersburg, 1907, p. 77).]

VDN was then unconditionally against capital punishment, no matter what crime, be it under common law, or special laws (various military codes), or even extraordinary laws (treason, wartime crimes, etc.). Eleven years later he found himself obliged to accept the latter when, in August of 1917, in his speech in the Petrograd City Duma, he, in the words of a colleague, "had valour enough to give support to Kerenski's government in its attempt to restore the death penalty in the army intoxicated by the revolutionary agitation. The fact that Nabokov, at that fateful moment for Russia, chose to make the judicial principle so dear to him subservient to his understanding of the patriotic necessity was a great sacrifice and a truly courageous civic feat." [A. Tyrkova, "V. D. Nabokov and the First Duma", in Russkaia Mysl', 1922, 6-7, pp. 282-3].

In Chapter One of his Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years , Brian Boyd points up a remarkable coincidence; the Manchester Daily Dispatch carried the report of VDN’s assassination in the very issue (of March 31, 1922) in which they placed his article regarding capital punishment received the day before and written, evidently, shortly prior to his violent death. (Another odd coincidence: this same issue prints the news of Lenin's rumored death). This posthumously published document, which the paper

[53]

calls "poignant", VDN's last invective against executions, advances the same moral argument, and turns for evidence to the same set of literary works, as the 1909 essay published infra,—which, needless to say, makes one recall some of his son's artistic schemes and public remarks on the matter. Since it is very little known, and since it is a rare example of V. D. Nabokov's English style, this little note is printed here unabridged and literatim:

"On the subject of capital punishment, discussed in the leading article of the Daily Dispatch of March 22, the attitude of the great majority of students of criminal law is quite definite.

"A series of objections to capital punishment that had been made in bygone days are now considered beside the mark. One of those objections was that capital punishment was not a deterrent. If this objection applies to capital punishment, it should apply even more to any other punishment. The logical deduction from this objection ought, therefore, to be complete renunciation of the present system of punishment by law, and reversion to the system of education, when possible, or of rendering the criminal innocuous if he cannot be improved. Nobody, however, advocates such a logical deduction.

"On the other hand, all efforts at appraising the effect of the abolition of capital punishment upon criminality, like all statistics of that kind, are doubtful. It is very difficult to make exhaustive and convincing investigations. When it was pointed out that the abolition of capital punishment in this or the other country was not followed by an increase in crime, the reply was that that the abolition of capital punishment is merely a result of the diminution of the criminal

[54]

elements in society. A controversy on this point might be carried on endlessly, but it leads nowhere.

"There is, however, another point of view, that of the Coroner of Durham. That is the ethical viewpoint on capital punishment, which has been expressed with striking conviction by the great analysts of the human heart. Suffice it to recall Victor Hugo's "Le Dernier Jour d'un Condamné," the description of Fagin's last night in Dickens's "Oliver Twist," Turguenev’s "The Execution of Tropman," and the wonderful pages of Dostoievsky in 'The Idiot." Dostoievsky, as we know, had been condemned to death and reprieved on the scaffold.

"These objections obviously presuppose a certain level of ethical perfection of the entire commonwealth. For this reason they presumably appear the least convincing to the present-day society.

"There is, however, another argument, which is particularly up to date at present in connection with the execution of Landru in France and the sentence of death passed in Berlin upon Peter Gruppen. It is the argument concerning the possibility of a judicial error. History proves that no criminal procedure, however perfect, is immune against such errors, which are always possible in such trials as that of Landru, when the evidence is entirely indirect.

"If there is anything which human conscience cannot tolerate it is the execution of an innocent person. Even in the eighteenth century, when humanity was somewhat less sensitive, the famous cases of Calas and Lesurques exercised a tremendous influence from that point of view. Special essays on judicial errors contain

[55]

numerous examples confirming the fact that these errors frequently occurred in the nineteenth century.

— V. Nabokov"

VDN dilates upon these points in his now almost forgotten essay published in the collection O smertnoi kazni: Mneniia ruskikh kriminalistov [Views of Russian Criminologists on Capital Punishment] (Moscow: Zveno, 1909). The book is so uncommonly scarce that, besides the citation in the Knizhnaia Letopis' for 1909 (item 9059), I could find only one reference to it (in N. S. Tagantsev's excellent Smertnaia Kazn', St. Petersburg, 1913, where from the footnote on p. 93 one learns that the French version of the 1909 collection was circulated among the participants of the Washington Congress on Prisons in 1910). In America, as far as I know, only Harvard has a film copy—which I have not seen. When translating this little essay into English I had at my disposal only a transcription of it by Mme. Elena Nabokov who, while in Prague, copied in her beautiful long hand, in an oilcloth notebook, some of her late husband’s published speeches and articles. Her daughter, Mme. Elena Sikorski, kindly showed me the notebook and allowed its translation and publication.

In its original Russian, the thing is couched in V. D. Nabokov's usual strong, wonderfully lucid yet neutral language with its smooth, "rounded" syntax, "disdain for superficial eloquence" (Tyrkova) its precise terminology of a legal writer, and the reinforcing iterations of an orator and barrister. My English version often fails to render these special marks of V. D. Nabokov's rhetoric but aims above all at accuracy. In one instance I could not restore the text because of a slip of transcriber’s pen; I mark the place in a note. Words in elbow brackets were added to clarify the

[56]

meaning of the original. I thank Mr. Dmitri Nabokov for his editing of the translation; the University of Missouri Research Council, for its generosity; and the University of Illinois Library, for its hospitality.*

— — — — — — —

While not denying the enormous significance of the criminal and political aspects of the problem of the death penalty — indeed, completely accepting the notion that they ought to be put forth persistently, both in theory and in legislature, I submit that today this problem should be shifted to ethical grounds. It is imperative to state that, apart from philosophical and politico-legal considerations that speak against the death penalty with utmost conclusiveness, the unassailable and decisive fact remains that the death penalty is ethically inadmissible.

As late as in the end of the eighteenth century, arguments were <still> possible over the practicability and expediency1 of torture as a very important instrument of obtaining the truth in criminal procedure. The famous criminologist Muyart de Vouglans2 demonstrated in 1767 that for every innocent man tortured during the <preceding> hundred years there were thousands of terrible criminals who but for the application of this method would have gone unpunished; that torture ought to be preserved because no available substitute is sufficiently effective and suitable; and, lastly, he points up the ancient origin of torture and its widespread practice.

* © Copyright: The Vladimir Nabokov Estate and Mme. Helene Sikorski.

[57]

Can one fathom anyone accepting a debate on such grounds today and arguing that torture is <merely> an inept and inexpedient procedural method? Considering that even <a century ago> Alexander I3 proclaimed that the very term torture, inflicting as it does "shame and reproach upon mankind”, ought to be forever banished from people's memory, how totally absurd the people of the 19th and 20th centuries should find the idea of arguing with Muyart de Vouglans over the procedural merits of torture. Once the notion of the ethical inadmissibility of torture, so marvelously worded by Emperor Alexander I, has entered the common consciousness and been firmly implanted in it, all arguments concerning the right to use torture and its expediency become meaningless.

Another example is serfdom and the institution of slavery in general. Once people have realized that turning one man into another’s property is ethically inadmissible, any further discussion of the merits and flaws of serfdom has assumed but an academic, historical significance.

In the course of the 19th century, the morality of civilized mankind rejected special forms4 of the death penalty, as well as crippling corporal punishment, and we would now regard a person demanding the reinstatement of execution by breaking on the wheel, by pouring melted tin down the throat, etc., as a madman and moral monster.

It is from this, ethical, position that one should approach the problem of the death penalty, and this standpoint should prevail over all considerations of expediency which should take the back seat. The solution is furnished not only, and not so much, by rational considerations but above all by the dictates and interdictions of conscience. Assuming this point

[58]

of view, we can say that the question whether or not capital punishment is a deterrent should be of as little importance as the analogous argument over torture or crippling corporal punishment. From this viewpoint, even if it were possible to eliminate court errors altogether, even if justice were to become infallible, not one iota would be added <to arguments> in support of the death penalty, for the protest of our moral sense would still remain unsilenced.

An awareness of the moral inadmissibility of the death penalty can be gained not so much through logical reasoning as by appealing to the moral sense, to the conscience of civilised mankind. The first of the speakers debating the problem of capital punishment in the French Parliament made the following curious remark. He referred to a poll taken by one of his colleagues among the members of a French Magistrature. This poll revealed that all of the opponents of capital punishment had witnessed an execution and, conversely, none of its supporters ever had. This is a convincing example of the way the moral sense can be roused by an immediate impression.

A number of indications attests to the true relation of this moral sense, undaunted by a centuries-old burden of traditional prejudices, Philistine indifference, and misanthropic convictions to...5 In olden days executions were performed publicly on holidays, for all the masses to see and with pompous solemnity. Nowadays, the very procedure of the execution tells one that something horrible and repulsive is being done. For those who must attend the execution this duty is a painful, often unbearable experience. The unwilling witnesses have been known to develop mental illness owing to the impressions received during executions.

[59]

The instinctive protest of our moral sense also manifests itself in our attitude toward executioners. The Russian executioner has never been on the government's payroll, and vainly would we leaf through our State fiscal records in search for those special entries that were struck from the French budget. To carry out the death sentences, the government has to resort to the services of outcasts who have lost the last vestiges of moral sense. And as often as not even these people can bring themselves to accomplish their job only by getting drunk to the point of almost total stupor....

Our Russian literature (and I mean fiction, not legal writings) depicts this particular side of capital punishment with shocking force and clarity. A few pages of Turgenev ("The Execution of Troppmann'),6 from Tolstoy (Kryl'tvos's story in Resurrection),7 from Dostoevski (Prince Myshkin's story in The Idiot)8 are more convincing and incontrovertible than thousands of scholarly works and columns of statistical figures. They do not argue, they portray, hence their powerful effect. One cannot question them; one can only plug up one's ears and close one's eyes....