Download PDF of Number 26 (Spring 1991) The Nabokovian

In Memoriam

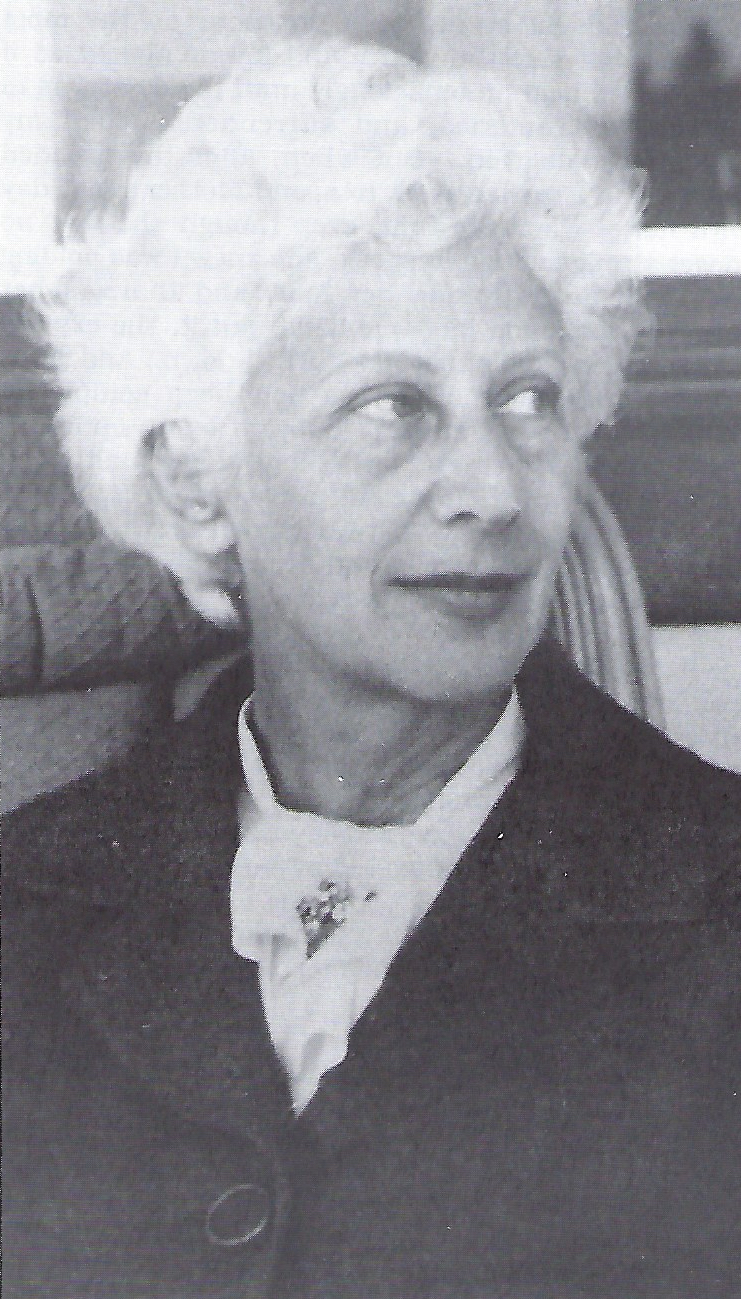

VÉRA NABOKOV

January 5, 1902 - April 7, 1991

On the morning of April 7, 1991, Véra Evseevna Nabokov, née Slonim, died in the Vevey, Switzerland hospital. She was buried at the hillside cemetery in Clarens overlooking Lac Leman. The following remarks were delivered at the funeral service in Vevey.

***

FOR MOTHER'S FUNERAL

11 APRIL 1991

On the eve of a risky hip operation two years ago, my brave and considerate mother asked that I bring her her favorite blue dress, because she might be receiving someone. I had the eerie feeling she wanted that dress for a very different reason. She survived on that occasion. Now, for her last earthly encounter, she was clad in that very dress.

It was Mother's wish that her ashes be united with those of Father’s in the urn at the Clarens cemetery. In a curiously Nabokovian twist of things, there was some difficulty in locating that urn. My instinct was to call Mother, and ask her what to do about it. But there was no Mother to ask.

[ii]

I miss most, perhaps, her nightly kiss on my accident-burned little finger, her nightly warning to drive or jog carefully even if I was traveling three hundred meters, and her desire for a phone call to reassure her that I was safe at bedtime, whether I was in Montreux or on some distant continent.

I shall miss her love and tenderness for the natural kingdom and the artistic one, and wish she could comment on my style even as I speak now. I shall remember, when I told her a pelican had made its way up to the 26th floor of a Florida tower, how she said "that's a big effort for a pelican," or her comment that the heart of a rhinoceros must be pounding in panic as it ran beneath the presumably harmless aircraft that was filming it. I shall remember, too, with what joy she read the great poets — even Dante and Leopardi who wrote in a language she had not been trained in — and the evenings we spent reading to each other Pushkin, or Lermontov, or Nabokov. I shall treasure the love she instilled in me for the great painters. I shall sorely miss the encyclopedic precision and splendid taste with which she assisted me on countless occasions.

Véra Nabokov was always reserved and modest about her important literary contributions. But even in her eighties she helped with the preparation of many editions of her husband's works, wrote an introduction for a Russian edition of his poems, assisted in the compilation of a collection of his letters, dedicated immense effort to the Russian translation of Pale Fire, and checked my first novel with a motherly but most objective eye. It is perhaps appropriate that some original research of hers, in connection with Pushkin's "Queen of Spades," has just been published by Ardis, in America, in a final, Nabokovian, issue of the Russian Literature TriQuarterly.

[iii]

[iv]

The saddest events seem to occur on the most beautiful days of the year. And it was almost as if Mother had held on tenaciously until the day I was to return from America, and surrendered when my arrival was delayed. But when, after the dreaded phone call, I rushed back to spend Mother's last day with her, I was sure that, even though she was no longer strong enough to speak, she knew I was holding her hand and stroking her hair, and that, as her faithful companion Madame Landi put it, she expired gently, like a candle that has burned down. And while her material incarnation has now been completely reduced to ashes, I am kept buoyant by an optimism that Father, Mother, and I have long shared: although we did not participate in any formal religious denomination, we have always known that things do not all end here, that pity and beauty are not wasted, and that one day we shall be rejoined.

It is sad to lose a loved one, but good to be loved. My love and thanks go to all those who have shown their affection by coming here today, or by writing, or by Calling. A few of you have said some words. Several faithful Nabokovians have sent small statements from far away. You have already heard some of them. There are two more, which I shall now transmit to you.

Professor Stephen Jan Parker, founder of the Nabokov Society and publisher of The Nabokovian, writes:

On such occasions American custom asks for personal testimony -- the recollection of special moments.

But my memory is crowded with myriad such moments, each of them special, precious, personal. In Judaic

belief it is held that personal immortality resides on this earth — in the lives of the people whom we have

touched. My life, in this regard, has been profoundly marked by the grace of

[v]

Véra Evseevna Nabokov — by the example of her selflessness, her concern for others, her maternal strength

and wisdom, her rigorous honesty, her intellectual strength, her powers of loyalty and commitment. And those

fabulous eyes — those blue, bright, radiant eyes that encompassed and sparkled and challenged — and made

one glad to be in her presence, and to be alive.

Brian Boyd, who gleaned much from Mother while preparing his superb biography of Vladimir Nabokov, says:

He dedicated his books to her; she dedicated her life to him. His genius, her loyalty, their love made a story

that readers the world over will not soon forget.

Vladimir Nabokov himself, in Speak Memory, wrote:

The years are passing, my dear, and presently nobody will know what you and I know. Our child is growing:

the roses of Paestum, of misty Paestum, are gone; mechanically minded idiots are tinkering and tampering

with the forces of nature that mild mathematicians, to their own secret surprise, appear to have foreshadowed:

so perhaps it is time we examined ancient snapshots, cave drawings of trains and planes, strata of toys in the

lumbered closet.

He also wrote, in a poem I have recently translated:

Good God, in this eerie, alien world,

letters of life, and whole lines, have been transposed by

the typesetters. Let’s fold our wings, my lofty angel.

Dmitri Nabokov

***

"Dmitri m’a demandé de dire quelques mots d’hommage à sa mère en français et de rapporter quelques témoignage reçus du monde entier pour saluer sa mémoire.

Véra Nabokov était vraiment, comme on dit en français, une très grande dame, d'une fidélité, d'un dévouement et d'une passion extraordinaires. Elle avait le sens du devoir et de l’amitié envers sa famille, son fils et son mari mais aussi pour tous ses amis à travers le monde.

Elle était une conscience formidable, un symbole pour l'histoire de la Russie exilée et d'un monde totalement disparu mais aussi une personne d’une immense érudition. En un mot elle était la meilleure spécialiste de l’oeuvre de son mari.

Ces dix dernières années, avec son fils, elle s'est dépensée sans compter pour organiser les archives de Vladimir Nabokov, veiller a l'unification de l'édition de ses oeuvres complètes, suggéré, amende et conseille des dizaines de chercheurs et d’éditeurs à travers le monde. L'un de ses projets les plus chers était la Pléiade des romans, actuellement en cours de préparation en France.

Sans Véra, il eût été impossible a Brian Boyd d'écrire sa biographie magistrale dont la publication a été saluée en Angleterre et aux USA récemment. Son ouverture d'esprit et son intelligence ont frappé tous ses interlocuteurs. II reste à rappeler que Vladimir Nabokov lui a dédié tous ses livres et que le dernier chapitre de Speak Memory (Autres Rivages) qui lui est consacré est assez éloquent.

[vii]

[viii]

Au moins aura-t-elle pu connaître le plaisir de voir les oeuvres de Nabokov paraître en Russie et le nom de Nabokov porté au firmament de la littérature russe par ses contemporains.

John Updike a dit "qu'elle était une dame extraordinaire et d’un savoir immense". Edmund White a dit, pour cette cérémonie, "Nabokov était un exilé fier et hautain, mais s'il était un exilé heureux, c’est parce qu'il avait Véra à ses côtes. Pour moi Véra était la lectrice idéale. Chaque fois que j' écrivais je la voyais comme mon interlocutrice: à la fois sereine, cultivée et exigeante."

(Nabokov was a proud and haughty exile but if he was a happy one it was because he had Véra behind him. To me Véra Nabokov was always the ideal reader. Whenever I wrote I always thought of her as my interlocutor: serene, cultured and demanding.)

Gilles Barbedette

***

(The following remarks came to The Nabokovian in the mail]

Those who knew her well knew that she was so much more than even the sum of the two paragons of a Russian writer's devoted wife, Countess T. in the young years of marriage and Mme D. in the last. During the fifty-two years of a supremely happy union, Véra Nabokov was, above all, a congenial wife, in the true sense of the French term of the previous century. Nabokov, of course, had been a vigorously blooming poet before he met her — indeed it was his poetry that at first engaged her interest in him -- but his serious prose had not begun until then. More than Nabokov's Muse, she accompanied him, if not steered him.

[ix]

towards the metaphysical possibilities in life that he quietly tested in fiction. Dedications to "Véra," invariably opening his English books, were not merely signs of gratitude or affection but also of earnest indebtedness.

But Véra Nabokov was a most gifted person in her own right. She possessed a combination of memory, imagination, curiosity, daring, erudition, and word-mastery of a quality that often make an artist, and it was an act of sheer self-stricting that she should have chosen to be an artist’s wife instead, his aide and inspiration. V.E.N. certainly had much to deny herself. Few realised, for instance, that she was an excellent scholar, with a keen and fresh eye, dry hand, and remarkable boldness, whose important discovery of a German source of Pushkin's "Queen of Spades" spawned a series of fruitful studies. Her filigree precision in matters of translation (which I, who have worked with her on many occasions, know so well), her firm conviction that playfulness and any other adornment, even if fortuitous, should always surrender to plain faithfulness, her unerring Russian accent, warded off numerous barbaric, albeit often well-meaning, attempts to translate Nabokov's English into exactly the sort of Soviet jargon that he abhorred. She had impeccable taste in language, one of the very last Russians with a genuine command of it, be it spoken or literary.

She was not universally liked: in this pedestrian, unceremonious, and disjointed age there were enough flat and out-of-joint people who found her aloof, much too majestic, and much too devoted to her husband and son. Such people, ranging from a wicked desert-writer who crudely coated a tasteless and callous libel with the flimsy film of fiction, to a pyknic critic who was miffed at V.E.N.'s disapproving of his feeding Nabokov with bawdy books and who passed his annoyance to

[x]

the public under the guise of a journal entry — such people would have been much more charitable to her, and to Nabokov for that matter, had both V.N. and V.E.N. been already married twice previously, the bumpier the better. A long and undiminished love can and does set certain minds ill at ease. But her friends knew how sincere, thoughtful, and true she was, and what heart-warming, lasting energy her quick, gentle, intelligent smile radiated.

Véra Nabokov was the daughter of Evsey Lazarevich Slonim, a St. Petersburg lawyer (kandidat prava), and Slava Borisovna, née Feigin, and for the benefit of those who like long distance ringing, the Slonims' telephone in Furshtadtski Street, 9, was 38-48.

Gennadi Barabtarlo

***

From the inception of the Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter in 1978, Mrs. Nabokov was a constant source of items for publication, information and encouragement. She never once questioned editorial policy or publication decisions. She took pleasure in the activities of the Society and the publication of its journal. The Nabokovian has lost its most steadfast supporter.

***

[xi]

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 26 Spring 1991

__________________________________________

CONTENTS

IN MEMORIAM: VÉRA NABOKOV i-x

News by Stephen Jan Parker 3

Nabokov Society News 13

Nabokov Society Bylaws 24

"...And I shall see a Russian autumn"

by Tatiana Gagen

translated by Jason Merrill 31

Annotation & Queries by Charles Nicol

Contributors: J.D. Quin, Gerard de Vries,

Gavriel Shapiro, S.E. Sweeney, Manfred Voss 40

ABSTRACTS

William Monroe, "The Jester Bells of Pale Fire 53

Roy C. Flannagan III, "The Revenge of the

'Gods of Semantics Against the Tight-Zippered

Philistines': The Ethics of Style in Lolita" 56

Marilyn Edelstein, "Nabokov as Romantic Theorist?" 57

Edith Mroz, "Nabokov and Romantic Irony:

The Contrapuntal Theme" 60

Karin Ingeborg Olson, "More There' than 'Here':

The Special Space and Time of Nabokov's Fiction" 63

[3]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

Nice Conference on Nabokov

A conference on Nabokov will be held at the University of Nice on June 24-25-26, 1992 on the following topic: "Biography, Autobiograph, and Fiction," a topic which is general enough to accomodate papers on anything from Look at the Harlequins! to Speak, Memory, and Brian Boyd's monumental biography, as well as on genre study. The proceedings will be published in a special issue of Cycnos, the Nice review of English Studies, and co-published perhaps by an American publisher.

The working sessions, all in English, will take place at the "Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines." The participants will stay in three-star hotels near "la Promenade des Anglais" (about $100, for room and breakfast); they will lunch in a restaurant near the Faculté and dine downtown. All expenses — travel to and from the conference, hotel, food — will naturally have to be covered by the participants themselves.

Anyone wishing to give a paper must send a one-page abstract to the organizer of the conference, Maurice Couturier, Professor at the University of Nice, before October 1. His home address: Maurice

[4]

Couturier, Professor, 31 Grange de Niel, 06780 St. Cezaire-sur Siagne, France; tel: (93) 60.28.78.

*

Michael Juliar writes: "I am offering a 110-page typeset update to and a copy of my 1986 Vladimir Nabokov: A Descriptive Bibliography. The refurbishment incorporates the 1988 update and includes additions and corrections to every section. The original bibliography's stock is about sold out and Garland is not going to print any more. I have acquired some of the remaining copies. Garland wants $88. I am asking $40 each, which includes a copy of the update. The update alone is at copying costs.

Prices (including postage) are: North America, $50; other than NA, $55/surface mail, $56-78/air (write for rates). Update alone, NA, $7.50; other than NA, $7/surface, $10/air. Payment must be in US dollars and must be drawn on a US bank to the order of Michael Juliar, 355 Madison Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904.

*

Mrs. Jacqueline Callier and Dmitri Nabokov have provided the following list of VN works received December 1990 - April 1991.

December —Tyrants Destroyed. London: Penguin reprint

— Vladimir Nabokov. Selected Letters. San Diego: Harvest/HBJ paperback, first edition.

— O Encantador [The Enchanter], tr. Manuela Madureira. Lisbon: Editorial Presenca, Collection Aura.

[5]

— Pnin. London: Penguin reprint.

January — La Defensa [The Defense], new translation by Sergio Pirol. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama, Biblioteca Nabokov.

— Le Don [The Gift], Lolita, Pnine, preface by Gilles Barbedette. Paris: Gallimard, Biblos edition.

— Eugene Onegin, tr. VN. Princeton: Princeton University Press, Bollingen Series LXXII, paperback second edition. Vol.I, introduction and translation; Vol.II, commentary and index.

— La Venitienne et Autres Nouvelles [thirteen stories], tr. from Russian by Bernard Kreise. Paris: Gallimard.

— La Defense Loujine [The Defense], tr. Genia and Rene Cannae. Paris: Gallimard, Folio edition.

— Hetscheermes [The Razor], tr. Anneke Brassinga. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij, promotion edition for Nabokov collected works which starts spring 1991.

February — Lolita, tr. E.H. Kahane. Paris: Gallimard, Folio reprint.

— Le Guetteur [The Eye], tr. George Magnane. Paris: Gallimard, Folio reprint.

— De Verdediging [The Defense], tr. Anneke Brassinga. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij.

— Wanhoop [Despair], tr. Anneke Brassinga. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij.

[6]

—Hetscheermes [The Razor], tr. Anneke Brassinga. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij.

— Ultima Thule [3 volumes containing A Russian Beauty, Tyrants Destroyed, Details of a Sunset], tr. Anneke Brassinga and Peter Verstegen. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij.

April — Regarde, regarde les Arlequins! [Look at the Harlequins!], tr. Jean-Bernard Blandenier. Paris: Fayard reprint.

— "Portrait of My Mother." In LC [Literary Cavalcade], Vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 32-35.

*

Odds and Ends

— The special Nabokov issue of Russian Literature Triquarterly, edited by D. Barton Johnson, has finally appeared (Ardis, 2901 Heatherway, Ann Arbor, MI 48104). The cover illustration, by Kathy Jacobi, is from her series of illustrations for Invitation to a Beheading, previously featured in The Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter (No. 10, Spring 1983). Number 24 in the series, the Nabokov issue is also the last issue of Russian Literature Triquarterly. During the twenty years of the existence of RLT, Nabokov-related items have figured prominently in its pages (see esp. numbers 3, 7, 10, 14, 16). As Ellendea Proffer notes in her remarks announcing the journal's demise, RLT "was the only thing like it in the Western world, and I doubt that there will be another journal dedicated exclusively to Russian literature any time soon."

[7]

— "The First Nabokov Conference In the Author's Homeland," by Mikhail Meilakh [Russkaia mysl (La Pensee Russe), No. 3834, 6 July 1990] presents a detailed report on the May—June 1990 USSR Nabokov Conference.

— Publication of Nabokov's works in the USSR continues apace. Full citations will appear in the annual bibliographies. Recent titles include: Ania v strane chudes [Alice in Wonderland], several volumes of short stories, Stikhotvoreniia [Poems], P’esy [Plays], new editions of The Gift and Pnin, along with individual stories and poems in various journals. Transparent Things and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight were announced for Spring 1991 publication.

— Brian Boyd’s Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years continues to receive wide acclaim and has been chosen one of the year's best by The New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Philadelphia Inquirer, Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and San Francisco Chronicle.

— Pekka Tammi notes: "you should give more credit on your pages to Roman Timenchik's "Pis'ma о Russkoi poezii Vladimira Nabokova" (listed in The Nabokovian 25, p. 71) and the Kniga edition of VN's prose edited by Dolinin and Timenchik (ibid., p. 68), as here dozens of Nabokov texts are made available that have so far been inaccessible even for a diligent Nabokovian."

— Tatiana Gagen, the author of "...and I see the Russian autumn," published elsewhere in this issue, has been one of the most ardent supporters and activists in the movement to restore the

[8]

Rukavishnikov house in Rozhdestveno. Her writings on the topic have been published in several USSR publications. She has argued strongly that the house/museum to be created at the site be devoted exclusively to the Nabokov family, rather than turning the house into a regional literary historical museum, in which Nabokov would be only one of several figures featured in the standing exhibits. Dieter Zimmer has recently published an article, lavishly illustrated, on the Rukavishnikov estate and the Vyra region, as well as the Nabokov's Petersburg townhome in Zeitmagazin (West Germany), 5 April and 12 April 1991.

— In the realm of VN and popular culture, several readers have pointed out the tasteless section in the February 1991 number of Elle magazine (American edition). The photospread, entitled "A La Lolita" and 'The Nabokov Look" reads: "The provocative style of modem literature's premiere nymphet is a la mode. When Vladimir Nabokov wrote 'Lolita' in 1955, he probably didn't have fashion in mind. How could he have known that dozens of designers would find Humbert Humbert’s fantasies so tantalizing?" Alfred Appel, Jr. in a note to the editor, remarks that "the young woman on display as The Nabokov Woman' is what VN called a 'post-post nymphet,' when I referred to Bardot, whom Simone de Beauvoir had called a nymphet." Incidentally, readers should be apprised that Vintage has recently released a new, revised edition of Appel's The Annotated Lolita.

*

D. Barton Johnson has just completed his teaching career at the University of California, Santa Barbara. In his penultimate semester's Nabokov course he gave the following final take-home exam (reprinted with

[9]

his permission). It occurred to the editor that given Don Johnson's well-known mastery of close Nabokov readings, the exam might be of general and/or specific interest. Readers might choose to adopt/adapt it for their classes, or simply take the exam themselves.

——

1. The exam, written in blue books or, better yet, typed, must be personally turned in to the instructor no later than.... Evidence of "cooperation" will lead to disastrous consequences.

2. All questions pertain to Nabokov's novel Transparent Things. In the following questions chapter numbers are referred to by Roman numerals, page numbers—by Arabic numerals. Use the same system in your responses. TT-Transparent Things; HP=Hugh Person.

3. Keep your answers brief and factual. Do not refer to outside sources. Give specific chapter or page numbers in support of your answers.

4. In the event of emergency, the instructor may be reached at...

EXAM

I. General questions. In no case should your answer be more than a few paragraphs in length.

A. Nabokov has referred to TT as "a ghost story."

Why? Comment.

B. What does the title Transparent Things refer to? Cite several passages in which this concept figures. What are its implications for this novel's narrator?

[10]

C. Who is the penultimate narrator of ТT, i.e., not Nabokov? What evidence can you offer in support of your answer?

II. Trace the following motifs (list page #) and briefly (2-3 sentences) comment on their structural role.

A. Fire B. Hands C. Nightmare/sleepwalking

D. Necks

III. Questions on Specific Points of Style and/or Structure.

1. Cull and list five of the alliterative pairs that Nabokov is so fond of, e.g., pain and plenitude.

2. Comment on the last paragraph of XI. How (and where) is it used again? Why?

3. Give two examples of how Nabokov uses italics for "special" purposes and explain.

4. Ditto for (parentheses).

5. Give a brief stylistic commentary on the following sentence: "Now the flames were mounting the stairs, in pairs, in trios, in redskin file, hand in hand, tongue after tongue, conversing and humming rapidly" (p. 103).

IV. Observant reading.

1. Who sets the final fire? Why? What evidence can you cite for your answer?

[11]

2. Whence the odd and not very accurate description of HP on p. 4 (end of paragraph) as "fantastic majesty"? Why is this page so "blurred"?

3. Page 5, last sentence. What difficulties?

4. Page 14. What is the "trim metaphor."

5. At what point in Chapter XVI does the reader first become aware of HP’s situation? What is it?

6. Pages 73-74. What is the coincidence Hugh refers to here?

7. Explicate the puns on pp. 82-83.

8. Who is the wе оп p. 1?

9. Whence, why, and who is "the green figurine" on p. 101?

V. Briefly comment on the following:

1. Tara Cataract (11) 2. Reubenson (30) 3. Doppler shift (80) 4. Figures in a Golden Window (26) 5. Mr. Wilde (98ff) 6. A "Lutwidgen" (40) 7. Giulia Romeo (80) 8. Adam von Librikov (75) 9. "balanic plum" (75)

*

The editor apologizes for the tardy appearance of this issue due to unexpected circumstances. Henceforth, subscribers can expect the Spring issue in late May, and the Fall issue in early December. Timely renewal of subscriptions in the fall would be most appreciated, as would timely announcement of

[12]

change-of-address. We are happy to announce that there will be no change in subscription costs for 1992.

*

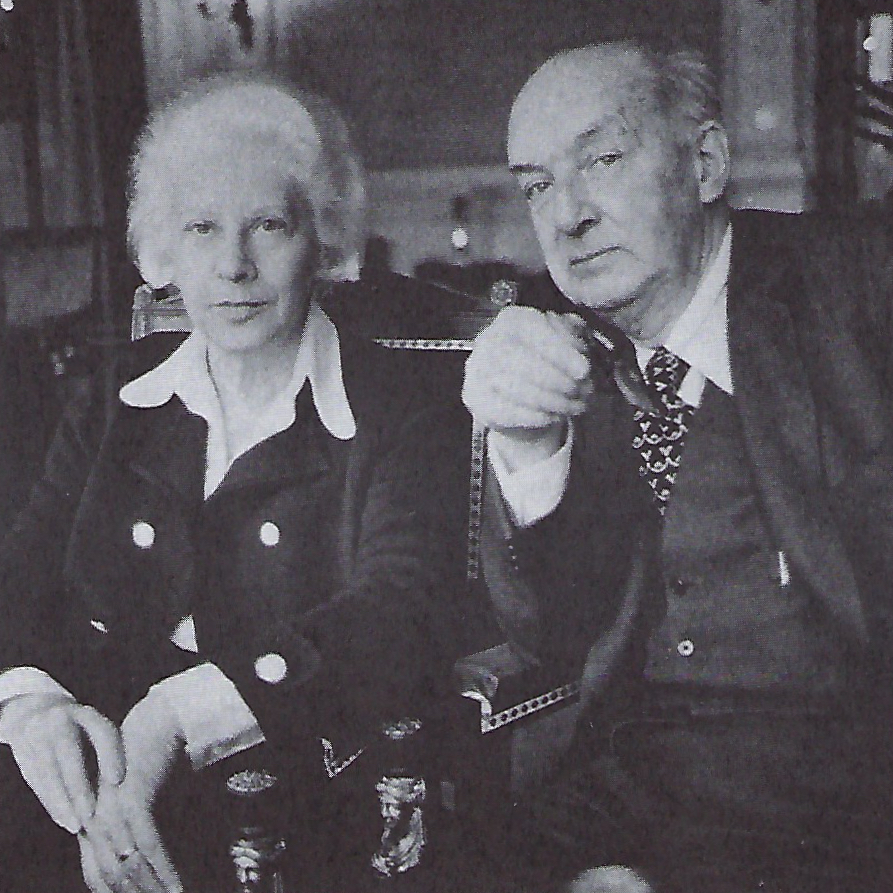

Photographs: page iii, Véra Nabokov, Villars, 1961, credit Topazia Markevich; page vii, Véra and Vladimir Nabokov, Montreux, early 1970s, credit Jill Krementz.

*

Our thanks to Ms. Paula Malone for her continuing, invaluable aid in the preparation of this issue.

[13]

NABOKOV SOCIETY NEWS

1990 MLA Meetings

I. The session on "Vladimir Nabokov as Stylist" was chaired by Samuel Schuman. His opening remarks and introduction of speakers were as follows:

'This is the whole of the story and we might have left it at that had there not been profit and pleasure in the telling; and although there is plenty of space on a gravestone to contain, bound in moss, the abridged version of a man's life, detail is always welcome."

The second paragraph of Nabokov's Laughter in the Dark makes a tidy and appropriate epigraph for this morning's session of "Vladimir Nabokov as Stylist." While Nabokov's authorial virtues are many and surprisingly varied, it is the pleasure and profit of the telling, the always welcome details, wherein we find his most stunning excellence. Nabokov is, at least some times, a satirist, a moralist, a caricaturist but most of all, he is a stylist.

The watermark of Nabokov's unique style is imprinted throughout his work: our papers today focus upon stylistic issues in two novels, a short story, and the semi-non-fictional autobiography. I am delighted to introduce these four quite differently stimulating papers. In order to save time, and also to allow (in the manner of Christopher Sly in the Taming of the Shrew) the disappearance of the narrative frame. I’ll introduce all four at once, to be presented directly one after another.

[14]

I have been very stern in limiting the presentation time of each panelist to 15 minutes: we will see if my severity actually accomplished its desired end. If, by some weird chance, someone should run over, I will be so rude as to chime-in with a reminder after a quarter-hour!

Roy C. Flannagan's paper is "The Revenge of the 'Gods of Semantics against the Tight-Zippered Philistines': The Ethics of Style in Lolita;" next will be "The Art of Retrospect: The Nabokovian Long Sentence in Speak Memory,” by John Burt Foster, Jr. Third, Shawn Rosenheim will speak on "'but Will the Mind of the Explorer Survive the Shock?’ Catachretic Style in Nabokov's 'Lance'," and the final paper is William Monroe's The Jester Bells of Pale Fire."

In the "Chronology" of Nabokov's life included in the prefatory materials for Selected Letters 1940-1977, the sole entry for 1940 is the rather abrupt "Arrives in America." Speak, Memory, of course, concludes with the beginning of that happy journey, the end of which brought our author to our shores 50 years ago. This session, devoted to Nabokov's manipulation of his adopted language, commemorates that half-century anniversary."

submitted by Sam Schuman

II. The session on "Nabokov and Romanticism" was held in the Picasso Room of the Hyatt Regency on December 10, 1990, at 1:45 pm., with Edith Mroz presiding. Even though this was the very last session of the four-day convention, attendance numbered 35.

Four papers were read. James O'Rourke of Florida State University, presented "Nabokov and the Ethics of Romantic Autobiography." This paper dealt with the narcissistic autobiographer in Lolita, Rousseau's

[15]

Confessions, and Wordsworth's Prelude, with comments on motivation from Capellanus' The Art of Courtly Love.

Philip Sicker, of Fordham University, presented "Pale Fire and Lyrical Ballads: the Dynamics of Collaboration." Exploring the "psychological dependencies and creative tensions" of the Wordsworth-Coleridge collaboration as "echoed" in the John Shade-Charles Kinbote relationship, this paper raised questions on parasitism and art.

Marilyn Edelstein, of Santa Clara University, presented "Nabokov as Romantic Theorist?" This paper drew distinctions between Nabokov and two kinds of precursors — "pure" aestheticism and Romantic theorists such as Shelley concerned with the moral element in a work of art.

Edith Mroz, of Delaware State College, presented "Nabokov and Romantic Irony: the Contrapuntal Theme," linking Friederich Schlegel’s theories on 'transcendental buffoonery," self-parody, and mirror-play in the modem novel with Nabokov's dialectic of narrative deception and romantic enchantment.

A brief question and answer session ensued, and continued after the session was formally ended. Most of the panelists had distributed handouts with key quotes: in addition, a handout and signup sheet were available to encourage those present to join the Vladimir Nabokov Society.

submitted by Edith Mroz

[16]

1990 VN SOCIETY BUSINESS MEETING MINUTES

The Society's annual business meeting was held from 9:45 to 10:15 am on Friday, December 28, at the Hyatt Regency in Chicago (as previously announced in The Nabokovian, the MLA Convention News, and on bulletin boards at MLA and AATSEEL). The meeting featured a report on the status of the Society and the Nabokovian; discussion of ways to facilitate selection of topics for future MLA sessions: the selection of topics for next year's sessions: and plans for social events at next year's conventions in San Francisco.

Susan Elizabeth Sweeney, president of the Society, read from a report by Stephen Jan Parker, secretary-treasurer and editor of The Nabokovian, in which he remarked that there was a sufficient level of subscribers and submissions for the journal to continue in its present form—although he was grateful for the interest and enthusiasm of all those who had suggested possible changes. Parker added that he would like to encourage anyone who presents a paper on Nabokov—whether at the MLA, AATSEEL, or elsewhere—to send an abstract (500-600 words) for publication in The Nabokovian.

The business meeting next discussed how the Society chooses topics for the sessions it sponsors. Several officers and members felt that the current method—proposing, discussing, and selecting topics during the business meeting itself—was too impromptu and ad hoc. The recent publication in The Nabokovian (25:5-6) of past session topics, following a suggestion made at last year's business meeting, will help to facilitate more thoughtful planning of future topics. The president made two additional suggestions: first, that the vice-president be given the additional task of chairing one MLA session during his or her two-year term; and second, that members propose topics for

[17]

sessions in advance through The Nabokovian. These suggestions were accepted and immediately implemented. Gennady Barabtarlo, vice-president, agreed to chair one session in San Francisco next year, and Susan Elizabeth Sweeney, president, encouraged members to propose topics for the 1992 convention by consulting the list of past topics in The Nabokovian and sending a proposal to Stephen Jan Parker at The Nabokovian by March 1 or September 1, 1991.

The next order of business was the selection of topics for next year's sessions at the MLA. Gene Barabtarlo will chair one session with an open topic; Marilyn Edelstein will chair another session, which she proposed, on "Feminist Approaches to Nabokov." The Nabokov Society will also sponsor an AATSEEL session, chaired by Christine Rydel, on "Art in Nabokov."

The president also proposed a social event to be held in San Francisco next year. She outlined several advantages of such a social event; it would attract new members to the Nabokov Society and offer them an opportunity to meet other Nabokov scholars; it would provide an opportunity to schedule the business meeting for an appropriate and convenient time (rather than giving up one of our two MLA sessions, or appending the business meeting to one of them); and it would allow members of the Nabokov Society who attend AATSEEL to attend the business meeting as well (one does not have to belong to the MLA or register at the MLA convention to attend a scheduled social event). Most important, it would encourage exchange between all interested Nabokov scholars; new and old, MLA members and AATSEEL members. Zoran Kuzmanovich suggested that an open cash bar, in particular, would be the most appropriate way to facilitate such an exchange. The open cash bar, could be followed, then, by dinner in a restaurant, for which

[18]

interested Nabokovians could sign up prior to the convention. Marilyn Edelstein and Geoffrey Green, who live near San Francisco, agreed to make the necessary arrangements. The business meeting then ended — with the hasty surrender of our room to another session, but with the promise of a more leisurely get-together in San Francisco.

After the business meeting, a few members of the Society made additional suggestions, and next year's schedule was planned in more detail. Gennady Barabtarlo suggested that the Society explore the possibility of awarding an annual prize—for the preceding year's best published essay on Nabokov, or best conference paper on Nabokov--to encourage Nabokov studies and recognize excellence in Nabokov scholarship. This idea will be discussed in more detail at next year's business meeting. Edith Mroz suggested that the Society prepare a one-page handout which would list the officers and their addresses, describe The Nabokovian, announce forthcoming sessions and social events sponsored by the Society, include a tear-off sheet for joining the Society and subscribing to The Nabokovian — and be distributed at all MLA and AATSEEL sessions on Nabokov. Such a handout will be prepared and distributed at the MLA and AATSEEL sessions in San Francisco next year.

The organization of sessions and social events in San Francisco was also planned in more detail after the business meeting. The MLA requires that all allied organizations scheduling two sessions hold one at a new slot on the first day of the convention. Accordingly, the society will request this schedule from the MLA: on December 27: "Nabokov: Open Topic," chaired by Gennady Barabtarlo, 3:30-4:45 pm, "Feminist Approaches to Nabokov," chaired by Marilyn Edelstein, 5:15-6:30 pm; on December 28: an

[19]

open cash bar, 5:15-6:45 pm (to be followed by a dinner organized by the Society, perhaps 7-9 pm).

Submitted by Susan Elizabeth Sweeney

Officers of the Nabokov Society

President (1989-91)

Susan Elizabeth Sweeney

Department of English

Holy Cross College

Worcester, MA01610

Telephone (508) 793-2690

(home): (508) 867-5041

Vice President (1989-91)

Gennady Barabtarlo

Department of German, Russian, and Asian Studies

University of Missouri-Columbia

Columbia, MO 65211

Telephone (314) 882-4328 (office)

Secretary-Treasurer

Stephen Jan Parker Editor,

The Nabokovian

Slavic Languages and Literatures

University of Kansas

Lawrence, KS 66045

Board of Directors

Julian Connolly

Slavic Languages and Literatures

University of Virginia

Charlottesville, VA 22903

[20]

Dr. Barton Johnson

Germanic, Oriental, and Slavic Languages

University of California

Santa Barbara, CA 93106

Charles Nicol

Department of English

Indiana State University

Terre Haute, IN 47809

Phyllis Roth Dean of the Faculty

Skidmore College

Saratoga Springs,

NY 12866

Samuel Schuman

Academic Dean

Guilford College

Greensboro, NC 27410

1991 MEETINGS - SAN FRANCISCO

MLA: "Vladimir Nabokov Society: Open Topic"

Presiding: Gennady Barabtarlo

"Feminist Approaches to Nabokov"

Presiding: Marilyn Edelstein

AATSEEL: "Art in Nabokov"

Presiding: Christine Rydel

Papers for the Barabtarlo MLA panel and the Rydel AATSEEL panel are set. Papers are still being sought by Marilyn Edelstein (Dept of English, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA 95053).

[21]

From suggestions made at the 1990 Business Meeting, participants in the "Open Topic" 1991 MLA session have provided abstracts of their scheduled talks:

"Nabokov and the Fiction of Self-Begetting."

The paper explores Nabokov’s creation of fictional characters from the point of view of what Steven Kellman has called the "fiction of self-begetting." Fiction of this type presents an account of the development of a character to the point where he is able to take up a pen and compose the novel we have just finished reading. This, of course, has obvious relevance to Nabokov. Among the issues my paper explores are the manipulation of character names in Nabokov, problems of parentage ("real" or imagined), self-reflexivity, literary allusiveness. In sum, the paper deals with the way Nabokov's characters attempt to fashion for themselves an identity or identities that may be more comforting than that which confronts them in everyday life.

'The Nabokovian in Nabokov"

The theme of this presentation is the individual peculiarities of Nabokov's style as they are expressed in his early Russian short stories. I single out a specific characteristic of Nabokov’s vision which can be defined as bent or inclined. This is confirmed by examining some of Nabokov’s specific phrasings and choice of epithets.

One of the reasons for this angled vision may be the literal meaning of Nabokov's last name, which in Russian translates as "sideways." I suppose that the style of every writer depends on the sound and the meaning of his own name. The style represents the

[22]

expansion of the name throughout the whole artistic universe. The names of Pushkin, Gogol, Dostoyevsky, and Tolstoy give ample evidence of the mystical connection between the aesthetic specificity of their writing and the semantic and phonetic structures of their names.

The other reason for the predominance of this angled vision is that it allows for the presentation of all objects and qualities in the moment of their disappearance, which was duly emphasized in one phrase of Nabokov: "My life is a perpetual good-bye to objects." The theory that Nabokov was a typical Westerner who was quite alien to the Russian spiritual tradition should be rejected, at least because of his deep roots in the apocalyptic outlook of Russian literature. Every object in Nabokov's writings is viewed at the edge of its existence, in an eschatological perspective, which makes Nabokov close to such thinkers as Soloviev and Berdiaiev.

Mikhail Epstein

"Nabokov's 'Terror' and Other Vastations"

Vladimir Nabokov's 1926 story Uzhas or ’Terror" provides a vantage point from which to survey both Nabokov's early intellectual milieu and the later scene in which he was himself an active participants. "Terror," a tale of existential vastation, contains certain echoes from literature, psychology, and philosophy. I argue that Tolstoy's "Dairy of a Madman," psychologist William James' Varieties of Religious Experience, and the writings of philosophers Immanuel Kant and Lev Shestov all lie in the background of Nabokov’s story. I further suggest that Nabokov’s use of these ideas in his brief tale underlies his subsequent hostility to J.-P. Sartre's

[23]

Existentialism which draws upon many of the same ideas.

Nabokov’s ’Terror" Is also the first formulation of a theme that will reverberate in the mature fiction for it as the earliest tale of madness to invoke the two world model that provides much of Nabokov's fictional cosmology: an "ordinary" world versus an imaginary one. This imaginary world assumes different forms in different works: Smurov's and

Luzhin’s delusional worlds in The Eye and The Defense; Cincinnatus' nightmare world in Invitation to a Beheading; the fantasy kingdoms of Sineusov and Kinbote in Ultima Thule and Pale Fire; and the antiworlds of Ada and Look at the Harlequins!. ’Terror" foregathers important pre-texts, artistically transforms them, and radiates its themes into a series of post-texts. Although perhaps not wholly successful as a work of art, ’Terror" is seminal in Nabokov's oeuvre.

D. Barton Johnson

[24]

NABOKOV SOCIETY BYLAWS

It has been pointed out that the original bylaws of the Society were published almost twelve years ago, and that it might be time to reprint and revise them. Among suggestions for revision are the inclusion of more specific, detailed descriptions of officers' duties, which would be consistent with actual practice over past years.

Article VII, Section В of the Bylaws states:

"...further amendments to the bylaws must be submitted

in writing to a business meeting of the Society, and must be

received by the Board of Directors at least 24 hours previous

to the meeting."

In order to aid members who might wish to propose revisions we reprint the existing Bylaws of the Vladimir Nabokov Society, ratified December 1979.

BYLAWS

VLADIMIR NABOKOV SOCIETY

I. NAME

The organization shall be named the Vladimir Nabokov Society.

II. PURPOSE

The Vladimir Nabokov Society is dedicated to the appreciation of the writings of Vladimir Nabokov, to the exchange of views and information concerning these writings, and to the fellowship of their readers. To these ends the Society has established a Newsletter, annual meetings, and a system of governance. All

[25]

further projects undertaken by the Society shall be evaluated in the light of these considerations and commitments.

III. MEMBERSHIP

A. Membership in the Society is open, upon payment of membership fees.

B. There shall be two classes of membership.

1. REGULAR MEMBERS. Individuals paying annual dues to the Society, at rates established by the Board of Directors, shall thereby become active members. They shall receive the publications of the Society, have the right to vote on all issues presented to the membership, and be eligible to hold offices and serve on committees. Regular members shall have one and only one vote in all issues submitted to the membership for determination.

2. INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERS. Institutional memberships shall be available for universities, libraries, or other bona fide institutions and organizations, at rates established by the Board of Directors. They shall receive all information and materials authorized for distribution as part of the privileges and rights of membership, but shall not have the right to vote or hold office.

IV. MEETINGS

A. The annual meeting of the Society shall be held in December, in conjunction with the Modem Language Association Convention.

[26]

Additional meetings may be called at the discretion of the Board of Directors.

B. The meeting shall consist of the Program and the Business Meeting.

1. The Program shall be conducted by the Program Director or other person designated by the Board of Directors It shall be open to the public.

2. The Business Meeting shall be conducted by the President, or in case of absence, the Vice-President, through the succession of officers. It shall be restricted to voting members of the Society.

a. An agenda shall be printed in the Newsletter or other previously mailed material or

shall be available from the Board of Directors no less than 24 hours before the meeting.

Any member may propose additional business from the floor.

b. The voting membership present at the meeting shall constitute the quorum needed to

carry on business matters. A simple majority of those present shall decide an issue, but

any individual or the Board of Directors may ask that a given action be confirmed by the

vote of the entire membership of the Society, in which case general membership participation

shall be obtained through the Newsletter or a mailed ballot.

[27]

c. Proceedings of any business meeting shall be reported to the membership through the

Newsletter.

V. OFFICERS

A. The Editor shall be responsible for publishing the Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter and any other publications required by the Society. The Editor shall be appointed by the Board of Directors.

B. The Program Director shall conduct the Program at Society meetings, shall be appointed by his/her predecessor with the advice and consent of the Board of Directors, and shall serve a one-year term.

C. The other officers of the Society shall be elected by the membership. They shall include a President, Vice-President, and, at the discretion of the Board of Directors, a Secretary and a Treasurer. They shall take office on January 1 of the year succeeding their election. Officers antecedent to these bylaws shall be assumed to have taken their positions as of January 1, 1979.

1. The President shall serve for a two-year term and be ineligible to succeed himself/herself. The President shall be the chief executive officer of the Society, preside at business meetings, have the management of the business of the Society, and see that all orders and resolutions of the Board of Directors are carried out. The President shall be an ex-officio member of all standing committees and shall report to the Board of Directors on all matters within the

[28]

President's knowledge that may affect the Society.

2. The Vice-President shall be vested with all the powers and shall perform all the duties of the President during the absence of the latter and shall have such other duties as may be determined by the Board of Directors. The Vice-President shall serve for a two-year term and be ineligible to succeed himself/herself.

3. The officers of the Secretary and Treasurer may be instituted at the discretion of the Board of Directors. These officers shall then serve terms of two years, and these terms shall be renewable. Until such time, the power of Treasurer shall reside with the Editor, and the power of Secretary with the President and the Board of Directors.

a. The Treasurer shall be charged with the responsibility of paying authorized expenses

and preparing an annual report, to be approved by the Board of Directors.

b. The Secretary shall prepare the agenda for business meetings of the Society and shall have

such other duties as may be determined.

D. The Board of Directors shall appoint from among its members, or members of the Society at large, a committee to supervise nominations and conduct elections.

E. Should an officer resign or be unable to assume the duties of the office, the Board of

[29]

Directors shall appoint a replacement until the next designated meeting of the Society.

VI. BOARD OF DIRECTORS

A. The Board of Directors shall consist of all officers of the Society and the five previous presidents, provided they have maintained their membership.

B. The Board of Directors shall decide the policies of the Society, and shall approve all budgetary requests beyond ordinary operating expenses.

C. The Board of Directors may appoint committees to carry out projects initiated by the Board or the Society as a whole.

D. All actions of the board of Directors shall be reported to the membership by means of the Newsletter or other appropriate publication.

VII. AMENDMENT OF BYLAWS

A. These bylaws shall remain in effect until ratified, replaced, or amended at the next meeting of the Society.

B. After ratification, further amendments to the bylaws must be submitted in writing to a business meeting of the Society, and must be received by the Board of Directors at least 24 hours previous to the meeting.

C. Amendment to the bylaws, shall require a simple majority of those present at a duly constituted business meeting. The Board of Directors may ask that such amendment be confirmed by the vote of the entire

[30]

membership of the Society, through the Newsletter or mailed ballot.

D. Amendments to the bylaws required by the laws of incorporation shall not require ratification but shall be presented to the membership of the Society.

[31]

...And I shall see a Russian autumn.'

by Tatiana Gagen

translated by Jason Merrill

Exactly seventy years ago, a large family left Russia. A steamship carried a middle-aged man and woman into emigration, and their five children along with them. The oldest boy was twenty years old.

This young man, who was very proud of belonging to one of the richest and most prominent noble families of Russia, was an esthete, an anglophile, and according to his peers, "a monstrous snob." He would soon force emigre literary circles to speak of him, earn the restrained praise of Bunin himself, and at a mature age would write the sensational and scandalous novel Lolita, which it seems to this day has not been unravelled. He would receive reporters, come to know esteem and world-wide fame, and would change cities and countries with ease, but...until the end of his day he would not find a home.

He would take up residence in a chic Swiss hotel,... Not one interviewer would receive a straight answer to the question: "With your tremendous income, Mr. Nabokov, why don't you leave the hotel and buy a house of your own?

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov would take the answer to this riddle with him. But he would hide keys to this innermost of his secrets in his books: in his poetry, in the "Russian" cycle of novels, and in the semi-autobiographical Other Shores. For the careful reader of Mary, The Defense, Glory, and The Gift, this secret is transparent and obvious. It is the writer’s estate outside of St. Petersburg ("our Vyra" as he was used to calling it from childhood), and the house on this estate. It alone remained for Nabokov that one Home, nearby and inside which he could imagine his

[32]

existence. Any other place on earth could only be a temporary shelter.

While describing his life in Russia, Nabokov was inwardly transformed. As never before this author's voice became trusting, and his pen began to flow easily...

For many years Nabokov received no news from Russia, and he did not know what had become of his estate. Had it survived? Had it perished? At these times he was visited by a bitter vision: "The house has burnt down, and the groves chopped down, where I spent the days of my youth."...

This estate on the Oredezh river, and the river itself, with its "lazy bend,” and the as familiar as "your own blood circulation" route from "our Vyra” to the village of Rozhdestveno, and the long familiar 'birch-lyre" with its double trunk, this childhood heaven, his first young love, all of this came together for him in his concept of Russia, Motherland, and Home.

Returning to Russia was just as impossible as bringing back the happiness of childhood, for Nabokov knew how prophetic his own lines could turn out to be for him: "There are nights when I lie down, and maybe my bed will set sail for Russia..." But his memory stubbornly summoned new visions, and contradicting himself, the writer added: " But my heart, you really wanted it to be that way: Russia, stars, the night of the execution, and the entire ravine covered with cherry trees."...

In Russian émigré literature there is not a more sincerely felt nor more expressively written confession in which the bitter taste of foreign lands and the thirst for recovery of the abandoned Fatherland is expressed so keenly and tragically.

What exactly did this strange writer with a Russian surname leave behind in his native land? What did he

[3]

bid farewell to, watching from the deck of the steamship as the shores of his country moved further away? What did he hope to find once again, as from novel to novel he forced his lyrical hero, his second "I," to travel countless times the same route to his native Home? That road which he knew "by touch and by sight, as you know a living body.” And where is it, this cherished land, this "old wooden house shaped like a Christmas tree, painted pale green, large, sturdy, and unusually expressive, with balconies level with the linden branches, and verandas decorated with precious window panes." That river, "sparkling between banks of brocaded pond scum;” the bridge which "spoke under the hooves" of horses: the park "here dark under the pine branches, there illuminated by the foliage of birch trees, immense, dense, with many paths...” What was their fate?

Beyond city limits each season of the year is felt more keenly. It seems that there was not a more dismal day in that distant autumn than that day when I first came to Rozhdestveno. I happened to be in this area accidentally. I knew nothing about it, I was only here because of business concerns. I finally decided to go to the city, but there was not a bus and there would not be one for another hour and a half... The highway to Luga. The bend in the Oredezh. Log cabins. An old church built of red brick. Not a soul around. It is empty, grey, and bare.

Suddenly, high above the river, a house appears. It is two-storied, with a belvedere and white columns supporting a portico. A wooden staircase leads steeply up the hill. There is a sign: "Regional Museum." Next to the house is a park. The slightly rotted former main wing. Resounding, empty, dry rooms. Stands with random exhibits, someone's diplomas and certificates of good work under glass. From somewhere behind closed doors there are heavy footsteps, and a weak voice asks "who's there?” It is the caretaker of the museum.

[34]

"Excuse me, whose estate was this?

"A man lived here, but I don't remember what his name was. They say that he owned another house on the other side of the river. They used to come to visit him from Batovo, Ryleev's former estate. Of all the old estate homes in the area, this is the only which survived."

She sighed: "The war..." She was quiet for a while, then suddenly suggested: "There is one thing that has been saved from those times. Would you like to look at it? I'll get it..." She returned with a thick photo album in her arms. She unlocked the bronze buckle and opened to the first page. She shook her head: "That’s how they once lived," and left. The precious family photograph album remained in my arms. This was the only surviving relic which preserved memories of the house, the people who once inhabited it, and the life to which there is no return. This alien life known to us through the stories of Bunin and Chekhov looked out form these pages, and the pictures themselves could be looked upon as illustrations to famous stories. At that time the name of the writer Vladimir Nabokov was not very well known in his motherland. Therefore there were very few who would think of looking for photographs of his parents in an old album stored in a regional museum. Moreover, who could draw an analogy between the detailed descriptions of artistic landscapes in his novels and the real lands of the backward "Leninets" collective farm of the Gatchinskii region of Leningrad oblast, which was, and remains, the main landlord?

At this point in my narrative I cannot avoid telling the story of the rural architect Aleksander Semochkin, local resident and expert. According to his own words, "five generations of my ancestors lived here, grew old, died, and now lie in the Rozhdestvenskii cemetery." Here is his story.

[35]

"What is the Upper Ordezh for me and every Russian? Holy places. The Runov estate is here, the place where Pushkin was almost born. (As his mother Nadezhda Osipovna was about to give birth, she left for Moscow and bore our genius there.) The first owner of the estate was Abram Petrovich Gannibal... Now the house is not cared for, being passed from owner to owner. Not far from here is the village of Kobrino, where Arina Rodionovna was born; her home, fortunately, is intact. Derzhavin often stayed in Orlino, and in Zarech’e was the estate where the architect Domenic Trezini lived and died in his manor. Ryleev lived in Batovo, and his mother is buried in the Rozhdestvenskii cemetery. Petrov-Vodkin and Kramskoi painted their pictures here. Shiskin lived here nineteen years, and all of his later works were written here. In the Rozhdestvenskii cemetery his second wife, the artist Ol'ga Lagoda, is buried. She was one of the first women to be accepted into the Academy of Arts. The artist and philosopher Rerikh lived in Izvar, after having laid down a spiritual bridge to the East. Nabokov, whose childhood was spent right here on the Oredezh, united Russia and the West. That's what kind of surprising places are here in this land which has attracted so many geniuses. What happened to it, how it deteriorated — you yourself can see, you have eyes."

Before I continue to the most depressing part of my story, I will tell you about something else. The Nabokovs owned three houses in the area. The first, "our Vyra," came to the family in the dowry of Elena Ivanovna Rukavishnikova, Vladimir Nabokov's mother. In this house he made his entrance into the world, her first bom, the future famous writer. The Nabokovs owned the house until the Revolution. In the 1920’s a veterinary school was organized here, and at the end of the 1930’s children of Spanish republicans were housed here. In 1942, before setting off for the southern front, the headquarters of Fieldmarshal Paulus were here. In 1944, during the retreat of the German forces, the estate home was

[36]

destroyed by fire. Only sad recollections about the manor, the once shady park, and the miraculously preserved man-made hill "Pamas" have survived to the present. In 1857 the writer’s grandfather on his father's side bought the house in Batovo which had once belonged to Ryleev. The Nabokovs owned it until 1917. Under the Soviet government a people's club was founded here. In 1925 the house and its wings perished from a nighttime fire, and burned to the ground. It is true that the estate park was saved, but it has been neglected. It is also surrounded on three sides by housing and the industrial zone of the local poultry processing plant with its waste treatment buildings. And finally we come to Rozhdestveno. This "house with the columns," as they have long called it in the area, is the only memory we have of Nabokov.

However, we shall have to start from afar: the house is at least one hundred fifty years old. Once Paul I awarded the village of Rozhdestveno to a certain Efremov. At the beginning of the last century he built a manor with columns and a belvedere on the most beautiful spot, a high bank above a bend in the Oredezh. He destroyed the wonderful park and built an open-air theater. He owned the estate for forty years. After his death it changed hands many times, until Elena Ivanovna Rukavishnikova's father bought it at the close of the last century. Her parents died early, and as a young boy Nabokov found himself the owner of the estate of his mother's brother, Vasilii Ivanovich Rukavishnikov, a diplomat who rarely travelled to Russia. Having premonitions of an impending death, he declared that his favorite nephew would become the owner of the estate upon coming of age. The future writer did not have time to assume ownership.

In this house there is now a regional museum, which until recently did not contain a single authentic exhibit. Now there is one: that same old photo album. It was brought here once by either the son or grandson of the Nabokov’s cook, an older local man. He found it in his attic and could not bring himself to throw it out.

[37]

And where, the reader will ask, is all of that luxury for which the house was famous in this region: the marble floors, fireplaces, paintings, expensive furniture, the large, painstakingly selected library... Where are they? Long-time residents often recall how, during the second year of the Revolution, twenty or so carts of all sorts of goods were taken from the Rukavishnikov home. Where they were taken to, only God knows.

Let this document which I found in the archive of the Gatchinskii museum tell what this house was like, and how the young Nabokov found it. With astonishment and pain I read these pages, typed on an old "Underwood:"

"List of items of artistic value in the former estate of V. I. Rukavishnikov in Rozhdestveno of the Gatchinskii district and the decision of the Gatchinskii district local government concerning their transfer to the Gatchinskii museum. January, 1923.”

1. A list of sixteen oil paintings in gilded frames.

2. Seventy-six miniatures

3. Seven watercolor paintings.

4. China, delftware, crystal.

5. Bronze.

6. Twenty-four etchings and lithographs.

7. Minerals.

8. Eight hundred eighty-nine books in foreign languages.

9. Photographs, albums, and portraits in wooden frames.

10. Furniture.

[38]

Above is a list of works of art which were transferred to the Gatchinskii museum from "our Vyra."

Where are these things? What happened to them? Believe me, even the most qualified art historian, the head curator of the Gatchinskii museum, Adelaida Sergeevna Elkina, cannot answer this question. She has dedicated her entire life to searching for the treasures of the museum which disappeared during the war, among which were valuables from the Nabokov's Rozhdestvenskii houses.

Here is what bothers me most of all about this story. "Sometimes, having tom myself away from writing, I shall look out the window and see a Russian autumn," a lyrical hero of Nabokov once nostalgically sighed. Vladimir Nabokov passed away not having seen it once again. I am afraid that the time is not far away when the writer's native and familiar countryside will have changed beyond recognition. The old park around "the house with the columns" is being chopped down, and recently a concrete warehouse for construction materials was built in it. The house itself has become delapidated. The columns, once covered with white-primed canvas, having long since been bare, and some of them sway or tilt to one side. All that remains between them and the parapet are cracked and dark beams from the bannister. The floors have worn thin, and are now devoid of parquetry. The roof leaks, there is glass missing from the windows, and almost everywhere the shutters have been torn off. The Rukhavishnikov family crypt was robbed; for a long time the icon which was hanging in the comer was not touched, but now even it has been carried off. At the beginning of the century, two "pink dachas" were the ornaments of the local area. These were wooden buildings with unique finely wrought carvings. Now they are also doomed to be demolished. With an unshaking hand the director of the "Leninets" collective farm sold them

[39]

to private interests for next to nothing. The end to this bitter list is not yet in sight.

In the face of this barbarity, the directors of the regional museum axe powerless. Valerii and Evgeniia Mel’nikov, through whose efforts a small, but comprehensive exposition in the former Rukavishnikov house was founded, tirelessly knocked on every door of the local division of the Foundation of Culture, Inspectors of the Protection of Historical and Cultural Monuments, the Administration of the Leningrad oblast’ local government, and other high authorities. This all came to nothing. All that is left for us and them to do is dream about that time when the former estate house will become a real "reserve for the protected." Its visitors will look with new insight at the works of the world-renowned writer who once sadly admitted that "I have dreamed about this too long, too idly, and too wastefully."

Once Vladimir Nabokov uttered the following: "Of course it is easier for me than for someone else to live without Russia, because I know that I shall return... I will live there in my books." He is now returning. Only we should greet him in a more fitting manner.

[40]

ANNOTATIONS AND QUERIES

by Charles NIcol

[Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov's works will be to the most recent hardcover U.S. editions.)

NABOKOV'S CARDIOLOGY

On retrospective study of Nabokov's novels a high prevalence of cardiac pathology has been noted. A representative series of four patients are described with clinical information derived from the texts. Current management of the medical conditions detailed is discussed along with an explanation for the high frequency of their occurrence.

Case One

S.K., a young writer prone to suffering from headaches, neuralgia, insomnia and toothache, gave a history of "pain in my chest and arm" (89). This is typical of angina pectoris. Angina arises when the blood supply to the heart muscle is compromised, most often by the process of atherosclerosis or "hardening of the coronary arteries." Unchecked this can lead on to a myocardial infarction (M.I.) or "heart attack." Angina would be an unusual diagnosis in such a young man, as it usually occurs in middle age. A family history of elevated blood lipid concentrations (e.g. cholesterol)

[41]

might be expected. Such individuals are at higher risk of an inherited lipid disorder which would predispose them at a young age to the development of coronary artery disease due to atherosclerosis. S.K.'s mother, Virginia K, had a cardiac history and died from heart failure described by his brother as "Lehmann's disease," a rare form of angina (89). In fact this Condition does not exist and is a "Lehm" joke [for the layman—CN]. It may be no more of a joke, however, than the clinically accepted label for a poorly understood variant of angina known as "Syndrome X" where the coronary arteries appear normal. S.K. was then reviewed in Berlin by a physician who "discussed coronary arteries and blood supply and sinuses of Salva (sic]," the latter probably a reference to the sinus of Valsalva which is part of the venous draining of the heart. At the early age of 30 he appears to have suffered a "heart attack" (115), although whether this was a myocardial infarction remains in doubt. Further consultations with a Dr. Oates (106) and a Dr. Starov (185) occurred. His brother once stated, "I would get all the heart specialists in the world to have him saved” (202). His fate remains unclear.

Case Two

A fifty-year-old male of mid-European origin, H.H. initially presented in his early twenties complaining of "dizziness and tachycardia" (27). His other past medical history included long-standing dyspepsia (sometimes relieved by milk and radishes), haemorrhoids and prostatism in later life. A period of psychiatric in-patient stay was also noted. During his subsequent stay in America he described an episode where he developed "a quite monstrous pain in my chest" which was promptly associated with vomiting. This episode was almost certainly his first M.I. He then states that he managed to drive the next day, a

[42]

fact that in later years "no doctor believed" (240). And no wonder: today the management of an M.I. implies a 48-hour stay in a coronary care unit, treatment with "clot-busting" thrombolytic agents, and constant monitoring of the cardiac rhythm. He later gave a history of an incident post-M.I. where his "pulse was 40 one minute and 100 the next" (271). Today this story would lead the clinician to perform 24-hour ambulatory cardiac monitoring, as it is highly suggestive of the "sick sinus syndrome." This is a condition where the sino-atrial node (the heart's natural pacemaker) is faulty, often as a result of earlier damage due to ischaemic heart disease. Normal cardiac rhythm is easily restored by the insertion of a pacemaker. Sadly this was not to be for H.H. who died of a probable further coronary thrombosis on 16 November 1952 (5).

Case Three

An elderly Russian professor, T.P., teaching at an American campus, developed sweating and palpitations on leaving a bus (20-21). Electrocardiograms had already "outlined fabulous mountain ranges" (20). Perhaps of significance was his treatment as a child by a Dr. Belochkin (22); rheumatic fever would have to be considered as a diagnosis here as it is well known to cause long-term cardiac valvular sequelae and indeed is common in young children. T.P. later developed "a certain extremely unpleasant and frightening cardiac sensation" which was "not a pain or palpitation but rather an awful feeling of sinking and melting into one's physical surroundings" (131). Once again a 24-hour cardiac monitor would be helpful here to exclude transient dysrhythmias. Radiological examination was thought to show "a shadow behind the heart" (126). Today this would be more fully evaluated by

[43]

computerised tomography (CT) scanning and if a pulmonary cause was suspected then one would go on to perform bronchoscopy.

Case Four

The poet J.S. suffered from syncopal episodes from an early age (38). He suffered from asthma as a child and had a family history of cardiac disease, his father dying from a "bad heart" (35). The sudden nature of these episodes does not favor an epileptiform collapse but is more suggestive of a Stokes-Adams attack. During these, cardiac rhythm is disturbed and may cease transiently. Recovery is swift. Again 24-hour monitoring is useful in diagnosis and once again a permanent pacemaker is often curative. In 1958 he survived a myocardial infarction. However, sadly, shortly after this event he was murdered.

Discussion

These four cases represent only a fraction of the cardiac pathology detailed in V.N.'s novels and short stories. His clinical descriptions are accurate and beg the question, why were his characters thus afflicted? V.N. himself suffered from recurrent chest pains, which he described as "neuralgia" (Selected Letters 99). He too was once told that he had "a shadow behind the heart” (Field, Nabokov: His Life in Part 251). As a student at Cambridge he suffered from palpitations and changed from smoking Turkish cigarettes to a pipe (Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years 181). In 1948 he had a bronchoscopy which involved swallowing "a vulcanised rubber tube," an experience which he described as "controlled panic" (Field 253-54). He wrote, "I have often noticed that after I had bestowed in the characters of my novels some treasured item of my past, it would pine away in the

[44]

artificial world where I had so abruptly placed it" (Speak, Memory 95). Perhaps it was the case that the less treasured torments of his recurrent neuralgia and chest pains were bestowed on his characters detailed above in the hope that these too might pine away from his own existence.

—Dr. J.D. Quin, Stirling Royal Infirmary, Livilands, England

PALE FIRE AND THE LIFE OF JOHNSON: THE CASE OF HODGE AND MYSTERY LODGE

With the epigraph of Pale Fire Nabokov saddled his readers with a rather contumacious riddle:

This reminds me of the ludicrous account he gave Mr. Langton, of the despicable state of

a young gentleman of good family. "Sir, when I heard of him last, he was running about

town shooting cats.” And then in a sort of kindly reverie, he bethought himself of his own

favorite cat, and said, "But Hodge shan't be shot no, no, Hodge shall not be shot.

—James Boswell, the Life of Samuel Johnson

Is it Langton, Boswell, Johnson or the young gentleman we have to look after, or is it the cat which plays the key role? The young mem, a nonrecurrent passer-by, can be left aside and the same goes for Langton, certainly not the most colorful of Johnson's friends. Boswell and Johnson, however, are personalities so rich that similarities with Kinbote and Shade force themselves on the reader. Boswell as biographer more than once thrust himself into the foreground, as is very much the case with Kinbote.

[45]

And Shade has a lot in common with Johnson. Both wrote poetry, devoted a study to Pope, had happy marriages, and attempted, reluctantly and unsuccessfully, to abstain from liquor. But the differences are more numerous and serious than the similarities. Their views on the afterlife, for both a main concern, were in stark contrast. For Shade the hereafter held the promise of a reunion with his beloved daughter: "I'm reasonably sure that we survive / And that my daughter is alive." But Johnson was captured by fear: "No man can be sure that his

obedience and repentance will obtain salvation" (Boswell entry of 15 April 1778). It is, moreover, unlikely that Nabokov could have been attracted by the peremptory hypochondriac and his lecherous, dipsomaniac biographer. (The deficiencies in Johnson's character have been explicated with unwonted soundness of judgment by Walter Scott in only a few pages which, without being less well written, are more revealing than many a page of Boswell: see his "Samuel Johnson" in Biographical Memoirs I; The Miscellaneous Prose Works 3 (I860): 260-72). It seems therefore improbable that the pairing of the duos—Johnson and Boswell: Shade and Kinbote—can be a fruitful approach, and one can agree with Maaja A. Stewart who has studied the similarities in greater detail, that "they remain more different than alike" ("Nabokov's Pale Fire and Boswell's Johnson," Texas Studies in Language and Literature 30 [1988]: 239). Scrapping the persons mentioned in the epigraph as an onset for finding its clue leaves us with Hodge, the cat. (Johnson had a weakness for cats, such as Hodge, his other weakness being a propensity to stodginess.) Hodge is discussed only once in Boswell's Life. (The word "Hodge," however, reappears in a note stating that the expression "hodge-podge" can be "applied to all discordant combinations," which might imply that

[46]

Hodge was a tortoiseshell.) It seems therefore unavoidable to peruse the two books.

Apart from a very casual remark on Timon of Athens the main text of Boswell's Life seems to contain only one passage which, primafacie, is related to Pale Fire, the following remark by Johnson: "Modern writers are the moons of literature; they shine with reflected light, with light borrowed from the ancients" (29 April 1778). This immediately calls to mind the "pale fire" which is snatched from the sun by the moon. An illustration of Johnson's statement (in which the borrowing seems more topical than the reflecting) can be found in his Life of Pope: "It is remarked by Watts that there is scarcely a happy combination of words, or a phrase poetically elegant hi the English language, which Pope has not inserted into his version of Homer. How he obtained possession of so many beauties of speech, it were desirable to know. That he gleaned from authors, obscure as well as eminent, what he thought brilliant or useful, and preserved it all in a regular collection, is not unlikely" (ed. A.R. Weekes [London: W.B. Clive, 1917) 102). Pale Fire can be regarded as an equally distinct example. Numerous references and borrowings are recorded or woven into its text. In Strong Opinions Nabokov says, "I see myself as an American writer, raised in Russia, educated in England, imbued with the culture of Western Europe; I am aware of the blend, but even the most lucid plum pudding cannot sort out its own ingredients, especially whilst the pale fire still flickers around it” (192). However, gathering "beauties" has not been the main object of this borrowing and reflecting; the name-dropping in Pale Fire is primarily meant to focus the attention on the richness of his cultural inheritance. As Priscilla Meyer concludes in her panoramic study, "in Pale Fire Nabokov creates a drama in ten centuries of the intertwinings of the literary cultures of Russia,

[47]

Europe, and America" (Find What the Sailor Has Hidden [Middletown: Wesleyan UP, 19881 133).

Boswell's Life also contains a footnote which Kinbote has 'jotted down" in his "black pocketbook." This must be the fifth note added to Boswell's text for the year 1754, which contains the following remark by Johnson: "A fly. Sir, may sting a stately horse, and make him wince; but one is but an insect, and the other is a horse still." Kinbote is called a "botfly; a macaco worm; the monstrous parasite of a genius." Botfly larvae are parasitic in animals; the Encyclopaedia Brittanica gives the horse botfly first among the different families to be discussed. Here we see the moon-sun metaphor repeated: Kinbote is a parasite on Shade as contemporary authors borrow from their predecessors. Johnson's observation means that the botfly inflicts no lasting harm on the horse. In Timon of Athens Shakespeare wrote that the moon "snatches” her pale fire from the sun, while in Kinbote's retranslation from Uncle Conmal's version, the moon "steals" its light from the sea. But the sun "robs" as well; and when robbery is reciprocated, no lasting harm is done. During his discourse on Bernard de Mandeville's The Fable of the Bees Dr. Johnson noted that robbery might produce good, "not by the robbery as robbery, but as translation of property" (April 15, 1778). Literary borrowing turns into "literary evolution," a term used by Nabokov to describe Eugene Onegin, "a character borrowed from books but brilliantly recomposed by a great poet to whom life and library were one, placed by the poet within a brilliantly reconstructed environment, and played with by that poet in a succession of compositional patterns — lyrical impersonations, tomfooleries of genius, literary parodies, and so on" (Eugene Onegin 2: 287; 2: 151). So the fire which is fetched might be pale, but it is reflected with the brightest colors.

[48]