Download PDF of Number 27 (Fall 1991) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 27 Fall 1991

____________________________________

CONTENTS

News

by Stephen Jan Parker 3

Nabokov At The Berg 12

Wholes and Holes: The Nabokov Archives

and the Nabokov Biography

by Brian Boyd

Nabokov on the Moscow Stage: 30

Two Events in Moscow

by Brett Cooke and Alexander Grinyakin

Annotation & Queries 34

by Charles Nicol

Contributors: Gavriel Shapiro,

Dieter Zimmer, Charles Nicol

Ada’s Percy de Prey as the Marlborough Man 45

by D. Barton Johnson

1990 Nabokov Bibliography

by Stephen Jan Parker 53

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 27, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

[3]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

The Nabokov Montreux archives, following a careful and protracted search, have found a permanent home. In October the New York Public Library announced the acquisition of the archives for its Berg Collection. The official press release of this singularly important event for all Nabokov scholars is published in this issue.

The Berg Collection of English and American Literature is a well known collection of first editions, rare books, autograph letters, and manuscripts. It includes 20,000 printed items and 50,000 manuscripts covering the entire range of English and American literature.

On October 16, to celebrate the acquisition of The Nabokov Archive, a program was held at the New York Public Library which featured remarks by Dmitri Nabokov and Brian Boyd. A summary of Brian Boyd's remarks appear in this issue; Dmitri Nabokov's remarks will appear in a future issue.

The Berg has given processing of the Nabokov Archive its highest priority. Nonetheless, with one cataloguer working full-time, the complete process may take nearly two years, and until it is completed the Archive will not be accessible. Upon completion of the project. The Nabokovian will publish a checklist

[4]

of the entire holdings at the Berg so that scholars will know the precise contents of the Archive. Further information regarding the Archive, along with the complete texts of Dmitri Nabokov’s and Brian Boyd’s remarks, will appear in the first issue of Biblion, the New York Public Library’s newly named publication, which is scheduled to appear in fall 1992.

*

The second, final volume of Brian Boyd's biography, Vladimir Nabokov. The American Years was published in October to wide acclaim from early reviews: "Rich and colorful” (Atlantic Magazine), "Magnificent" (Kirkus Reviews), "A triumphant and definitive biography" (Publishers Weekly), "Stimulating" (Library Journal). Richard Locke, reviewer for The Wall Street Journal, writes: “In his biography Mr. Boyd gives us at last a reliable life and works—a portrait of a heroic artist and his beloved family, a scrupulous historical narrative of great energy and color, and strong, enthusiastic interpretations of the master’s literary works themselves, an admirable reader’s guide .... It is fortunate that Mr. Boyd doubles as a critic as well as a biographer. His commentaries are accessible, insightful, often original and always passionate. He is sedulously old-fashioned in his method and style, explicating themes and structures, confidently connecting author and text as if post-modern theory had never been born. He utters not a word of jargon.”

*

The 1991 Nabokov Society meetings will be held in San Francisco in association with the annual national conventions of the Modem Language Association (MLA) and the American Association for

[5]

Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages (AATSEEL):

(1) At MLA, December 27, 3:30-4:45 pm, Belmont Room, Hilton Hotel: "Open Topic," chaired by Gennady Barabtarlo (University of Missouri). "Nabokov and the Fiction of Self-Begetting," Julian Connolly (University of Virginia): "Nabokov's Terror' and Other Vastations," D. Barton Johnson (University of California, Santa Barbara): "The Nabokovian in Nabokov," Mikhail Epstein (Emory University).

(2) At MLA, December 28, 3:30-3:45 pm, Monterey B, Hilton Hotel: "Feminist Approaches to Nabokov," chaired by Marilyn Edelstein (Santa Clara University). "Limited to the Male's Perceptions: Colette, Lolita, and the Wife of Chorb," Charles Nicol (Indiana State University): "Producing Woman as Text: Narrative Seduction in Lolita," Sally Robinson (University of Michigan): "Kinbote's Transparent Closet in Pale Fire” Jean Walton (Fordham University); "Re(I)nventing Nabokov: A Critique of the Feminist Critique in Roberta Smoodin's Inventing Ivanov," Susan Elizabeth Sweeney (College of the Holy Cross).

(3) At AATSEEL, December 30, 10:15 am-12:15 pm. Room C: 'The Fine Arts in Nabokov," chaired by Christine Rydel.

*

At the annual convention of the American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies (AAASS), Miami, November 23, there was a panel on "Free Will vs Determinism: Author and Character in V. Nabokov's Fiction," chaired by David Bethea (University of Wisconsin). The following papers were presented: "Nabokov and the Pleasures of Fate,"

[6]

Vladimir Alexandrov (Yale University); "The Power behind the Throne: Author and Character in King, Queen, Knave," Julian Connolly (University of Virginia); "Author as Tyrant and Liberator," Sergei Davydov (Middlebury College); Discussant, Ellen Pifer (University of Delaware).

Also on November 23, at the panel titled "Ethics and Aesthetics in Modern Literature," Clare Cavanagh (University of Wisconsin) delivered the paper, 'The Ethics of the Auteur. Hitchcock and Nabokov."

*

Mrs. Jacqueline Callier has provided the following list of VN works received May - October 1991.

May — Feu Pale [Pale Fire]. Paris: Gallimard, Folio reprint.

June — Lolita. Paris: Gallimard, Folio reprint.

— Le Guetteur [The Eye]. Paris: Gallimard, Folio reprint.

— Mon Enfance Europenne [Speak, Memory]. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Verlag.

— Desespero [Despair], tr. Manuela Madureira. Lisbon: Editorial Presenca.

— Il Dono [The Gift]. Milan: Adelphi Edizione.

[7]

— Excerpt from "The Admiralty Spire." In Humoore, Zurich: Haffmans Taschenbuch 101.

July — Nikolai Gogol. Oxford: Oxford University Press, "Oxford-Lives" collection.

— "Scenes From the Life of a Double Monster." In They Chose English, Paris: Hatier.

— Vladimir Nabokov. A Pictorial Biography, compiled and edited by Ellendea Proffer, Ann Arbor: Ardis.

August — Ada. Tokyo: Hayakawa Shobo, reprint.

September — The Enchanter. New York: Random House, Vintage International paperback.

— Pale Fire. London: Penguin reprint.

— Speak, Memory. London: Penguin reprint.

— Autres Rivages [Speak, Memory], Paris: Gallimard, Folio reprint.

— Errinnerung, Spricht [Speak, Memory]. Reinbeck bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, Collected Works.

— Fruhe Romane I [Mary and King, Queen, Knave]. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, Collected Works.

— Roi, dame, valet [King, Queen, Knave]. Paris: Gallimard, Folio reprint.

[8]

October

— Selected Letters 1940-1977. London: Vintage Books.

— Laughter in the Dark. New York: New Directions, in "Revived Modern Classics," ed. James Laughlin.

— Poems. In Van Derzjavin Tot Nabokov, tr. Marja Wiebes and Margriet Berg. Leiden, Holland: Plantage.

*

Odds and Ends

— On September 26, the Milan Museum of Natural History opened to the public an extensive exhibit on VN the lepidopterist. The exhibit included boxes of butterflies (on loan from the Lausanne Museum) gathered by VN, with his descriptions; VN's lepidopterological writings; VN's books with butterfly references; VN's lepping materials; and more.

— Four previously unpublished poems by VN dating from 1916 have been published in the Leningrad Chas pik (22 July 1991), page 10, under the title 'la derzhal v ob’iatiiakh tonen'kii skelet' [I held in my embrace a slender skeleton]?" along with an extract from Brian Boyd's Vladimir Nabokov. The Russian Years, translated from the English by Galina Lapina.

— American Nabokovists are beginning to appear in print in Russia. To wit, an essay by Sergei Davydov (Middlebury College), "Nabokov and Pushkin," appears in the Leningrad publication, Nevskoe vremmia, 20 July 1991, page 5.

— As in indication of VN's popularity in Russia, the 1990 four-volume edition of his collected Russian

[9]

prose [see the 1990 Bibliography in this issue] was released in an edition of 1,700,000 copies.

*

Publications to note:

— VIadimir Nabokov. A Pictorial Biography, compiled and edited by Ellendea Proffer. Ann Arbor: Ardis. 1991.

— Nabokov's Otherworld, by Vladimir Alexandrov. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1991.

— Special Nabokov Issue, Russian Literature Triquarterly, No. 24, ed. D. Barton Johnson. Ann Arbor: Ardis. 1991.

— A Nabokov Who's Who, by Christine Rydel. Ann Arbor: Ardis. Announced for 1991.

*

Gene Barabtarlo writes: “Material evidence has been found that the author of Romance with Cocaine (a novel published in a Paris émigré almanac in the 1930s under the name of M. Ageev, which Prof. Nikita Struve has doggedly attributed to Nabokov, even in the recent Soviet edition of the book) was indeed Marc Levi, just as Nabokov’s widow maintained all along. Mr. Gabriel Superfine, a Russian philologist and bibliographer of enormous erudition, living in Munich, suggested some time ago that the school described in the book was the Moscow Kreiman Gymnasium. The émigré weekly La Pensée Russe (Paris) now reports that Miss Marina Sorokin, a Moscow scholar, has found the school’s archives which show that the names of the 1916 graduates, Marc Levi included, correspond to the names of the novel’s personae. An elaboration is promised.”

[10]

Dieter Zimmer, who is editor of the complete works of Nabokov in German, writes: 'The Rowohlt edition, now scheduled to have twenty-four volumes, is slowly progressing. This year, volume 1 (Mashenka and King, Queen, Knave) plus volume 22 (Speak, Memory) have been published. The epilogue to Mashenka contains some information on the further destiny of Valentina Shulgin; the one to King, Queen, Knave a reasoned account of the text differences between the Russian and English version, with many examples and the entire final chapter in both versions. The lengthy appendix to Speak, Memory contains, among other things, "Mademoiselle O" in French (and partly in German) and (similar to the new German Lolita) all passages from Drugie berega that are not in SM 1967 or that differ from it substantially (about thirty pages all in all). The German reader cannot reconstruct SM 1951 and Drugie berega from this volume (SM 1951, by the way, had been translated in the early sixties), but he now has everything Nabokov has ever written for this book. We hope to finally have the German version of The Gift out next fall, after twenty-eight (!) years of preparations, if my count is correct; it is the only novel that has been missing."

*

NABOKOVIANA

1. John DeMoss has forwarded a copy of Twin Peaks Gazette (April 1991), a seven page publication devoted to the cult TV show, "Twin Peaks." On page 3 the following "Letter to the Editors" appears:

[11]

Dear Editors:

With shock and despair, I read of the spontaneous combustion of Mr. Kabonov. I had a sense of transparent things, since it might have happened to any Ada or Lolita in Twin Peaks, and king, queen, knave. A walk in the woods could be an invitation to a beheading, an eerie look at the harlequins, a bend sinister that leads to laughter in the dark. Still, such pale fire might be a gift to all of us who will remember and learn from this. We can sit back and think: "speak, memory." It was a sad death for a chess player with strong opinions.

Michael Begnal

State College, PA

Yes, but. sadness perhaps relieved by a visit to the museum. Ed.

2. Also from John DeMoss, the answer to one of the puzzles on "La Ruleta de la Fortuna" (the Spanish version of "The Wheel of Fortune") broadcast October 2, 1991 on Antenna 3, Madrid. Note the telling spelling

[12]

Our thanks to Ms. Paula Malone and Ms. Ann Christine Rudholm for their invaluable aid in the preparation of this issue.

PLEASE NOTE: Subscription renewals are now due for 1992. Rates have not changed: check the inside cover of this issue. Help us avoid the additional postage cost of mailing renewal reminders by sending in your renewals now. It will be much appreciated and will help us maintain the present subscription rates.

[13]

NABOKOV AT THE BERG

NEWS RELEASE

THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY ACQUIRES VLADIMIR NABOKOV ARCHIVE

The New York Public Library has acquired the Vladimir Nabokov Archive for the Library’s Berg Collection. Nabokov (1899 - 1977) is one of the 20th century’s most important writers.

The Vladimir Nabokov Archive documents the creative process of an extraordinary man of letters throughout his working life. Among the remarkable assemblage of materials gathered, protected, and treasured by the author, his mother, his wife, and his son, are manuscripts, draft translations, and no less than thirty-one diaries. Other treasures include heavily corrected typescripts, proofs, and galleys, annotated teaching books, drawings of butterflies by the author, and correspondence. "The Archive," Berg Collection Curator Francis O. Mattson points out, "will allow scholars unparalleled opportunities to discover and explore in depth this great writer and his work.”

Over thirty albums of Nabokov's copies of his poetry written from 1918 to 1931 make up the earliest material as well as albums in which his mother lovingly transcribed his early work, sometimes pasting in Nabokov's own manuscripts and typescripts. The composition of Nabokov's last three novels, Ada, Transparent Things, and Look at the Harlequins!, is documented in unusually complete fashion in the Archive, by original 3x5 index cards for

[14]

each work in Nabokov's hand, as well as edited typescripts, proofs, and galleys.

Among the translations, of particular interest is an early version of his Russian novel Camera Obscura in English, which Nabokov later completely retranslated into English as Laughter in the Dark, providing what is a complete rewriting of the novel. The collection also includes Nabokov's 1969 translation of Lolita from the original English into Russian, a significant literary event and an adventure Nabokov found more difficult than the creation of Lolita itself. Nabokov's controversial translation of Eugene Onegin into English is represented by manuscripts, typescripts, and other documentation gathered for this labor of love.

Many earlier novels are represented in draft translation, such as The Gift and King, Queen, Knave. These translations can be considered new works, and provide a unique perspective into the creativity of a writer who was a great novelist in both Russian and English. Also of interest are several typescripts into the French (Pale Fire, Ada, The Eye) which Nabokov heavily corrected.

Another large group of materials centers around the biography and autobiography of the writer. The manuscripts for his autobiographical jewels, Speak, Memory and Conclusive Evidence are particularly inspiring. The thirty-one diaries (beginning in 1943) contain remarks on the progress of novels and stories, observations, ideas for future works, and transcriptions of dreams. The 1951 diary was mined by Nabokov for the next twenty-one years as a source for novels and short stories. Copious correspondence with friends, students, publishers, and translators round out this part of the Archive.

[15]

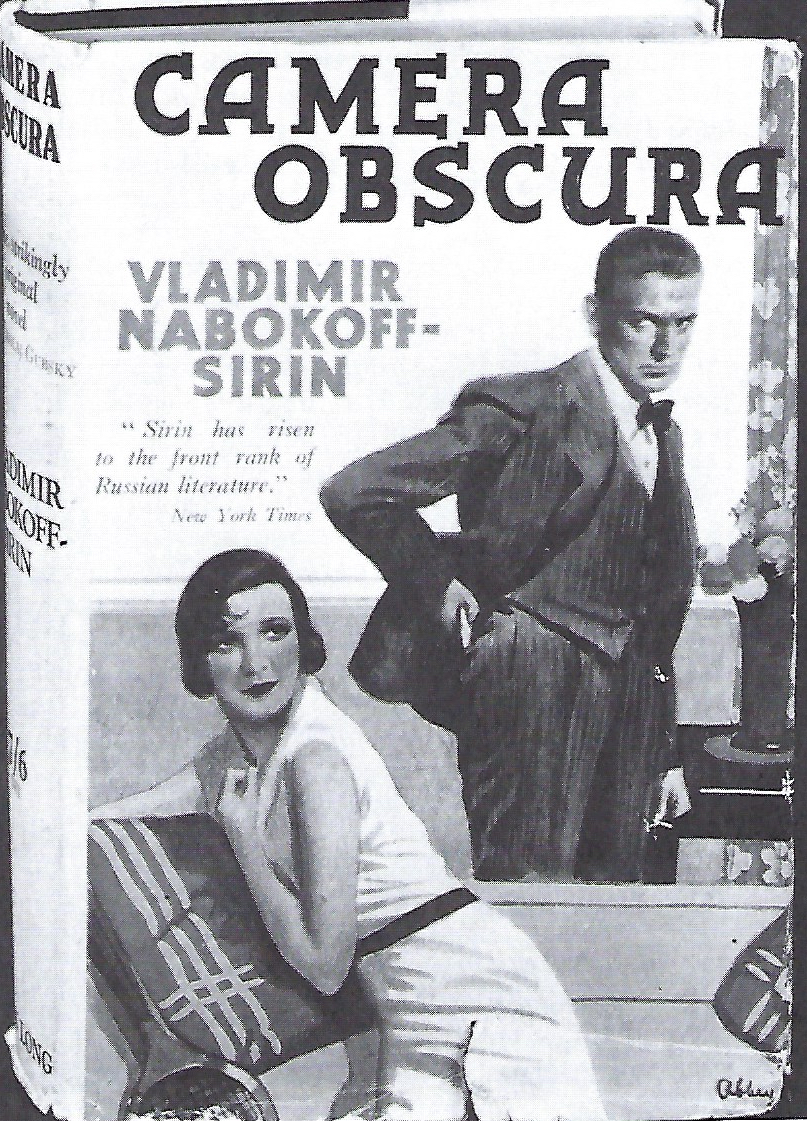

In Russia Nabokov used the pen name Sirin to distinguish himself from

his father, another Vladimir Nabokov. This 1936 British edition of

Camera Obscura, part of The New York Public Library's newly acquired

Vladimir Nabokov Archive, was considered "sloppy" by the author.

Photo: Peter Bittner/The New York Public Library.

[16]

The Archive includes many documents from Nabokov's teaching career at Wellesley and Cornell, including original manuscripts and typescripts for three lecture texts he wrote, and an important collection of annotated books he used for teaching (Madame Bovary, The Metamorphoses, Ulysses).

Nabokov the lepidopterist is represented by typescripts, corrected copies of his published works, unpublished works, and numerous drawings of butterflies by the author. These are joined by manuscripts of chess problems, another extracurricular interest that features strongly in his novels.

Finally, there are clippings, both loose and mounted in albums by Nabokov's wife and muse Véra, which document his literary career and reception by reviewers and critics. The Archive contains therefore an invaluable record of Nabokov's early publications since the émigré publications in which they appeared have survived often only in fugitive copies. Later reviews of his work were sometimes annotated by the author or his wife.

***

About the Berg Collection

The Berg Collection, one of the nation's most celebrated collections of rare books, was presented to the Library in 1940 by Dr. Albert A. Berg, a famous New York surgeon, in memory of his bother. Dr. Henry W. Berg. Dr. Berg's early love of Dickens eventually led to his purchase of a Dickens novel in parts, the genesis of the Berg Collection. The Collection covers the entire range of English and American literature, with special emphasis on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Among its treasures are the original typescript of T.S.

[17]

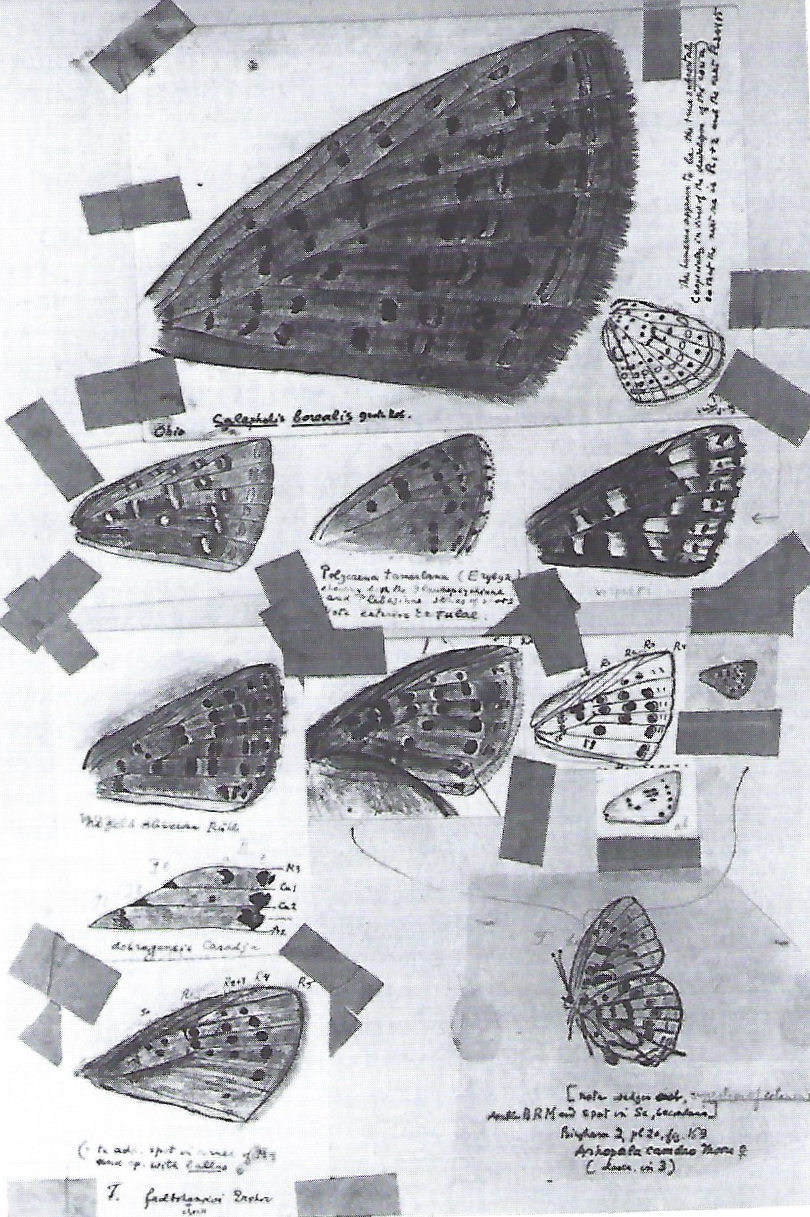

Nabokov the lepidopterist is represented in The New York Public Library’s

newly acquired Vladimir Nabokov Archive by numerous drawings of butterflies

— with often minute, detailed notations — by the celebrated author.

Photo: The New York Public Library.

[18]

Eliot's The Waste Land and the holograph novels, diaries, and letters of Virginia Woolf. In its 50-year history, the Collection has had only three curators. Dr. John D. Gordan, Dr. Lola Szladits, and current curator Francis O. Mattson.

[19]

WHOLES AND HOLES: THE NABOKOV ARCHIVE AND THE NABOKOV BIOGRAPHY

by Brian Boyd

On the occasion of the announcement that the New York Public Library had acquired the Nabokov archive for its Berg Collection, I was asked to speak on the subject of “The Nabokov Biography and the Nabokov Archive.” The complete text of the talk will be published in the New York Public Library’s journal, Biblion. Here are a summary and a sample.

The talk had several aims. First, to explain how strange it is that there is a Nabokov archive at all, and that it forms such a comprehensive record of his whole career (it is by far the largest single-author archive in the Berg Collection, which is famous for treasures like the manuscript of The Waste Land, Virginia Woolf's diaries, and a host of other major twentieth-century literary texts), given Nabokov’s theoretical hostility to biography and to the study and preservation of an author’s drafts and private papers, and his prior donation of many manuscripts to the Library of Congress. Second, to show how heavily reliant my Nabokov biography was on material in the archive, and yet to show how this material was nevertheless impossible at times to interpret without other data gleaned from interviews and Nabokov’s published work (including even his fiction). Third, to explain some of the structure I had tried to build into the biography. Fourth, to point out what remained unknown about Nabokov’s life, and why, and how it could nevertheless become part of the story of his life. And fifth, to pay tribute to Véra Nabokov, in the year of her death, for having amassed and preserved all this

[20]

material, despite the vicissitudes to which she and VN were subjected by history.

I began by citing the comparison Julian Barnes makes in Flaubert's Parrot between biography and a net: a net defined not as an object for catching fish, but as 'a collection of holes tied together with string." After detailing Nabokov’s hostility to biography, and history's collusion with him in erasing his traces, I pointed out the counter-forces that made it possible for such an extensive archive to be assembled: Elena Ivanovna and Véra Evseevna Nabokov, Nabokov's mother and wife.

Next, I explained how I had tried to shape the biography by establishing certain relationships between the art and the life, and between Nabokov's life of Nabokov in Speak, Memory and my version of his life, and between Nabokov's life and another, in each volume: his father's, in The Russian Years, his wife's, in The American Years.

Then I turned to the archive, showing how things like V.D. Nabokov's 1918 diary in the Crimea, VN's diary account of the night his father died and his letters to his mother after his father's death allowed me to make both V. D. Nabokov and his son's evocation of him in Speak, Memory into cornerstones of The Russian Years.

I concluded with Véra Nabokov. After describing Nabokov's way of making her central to Speak, Memory while never quite bringing her onstage, only by addressing her as You, I turned to Nabokov's last novel. From here I quote:

Look at the Harlequins! takes the form of an autobiography by a Russo-American writer called

Vadim Vadymich N___________, whose life is a bleak.

[21]

barren parody of Nabokov’s own, until at the end of the book a woman never given any name but

You steps into his life and turns it from rancor to radiance. Obviously it parodies, among a great

deal else, not only Nabokov’s life but his own account of his life in Speak, Memory.For a long time after I realized this much about the novel, it still puzzled me. Its self-referentiality

seemed sterile and sour. But as I began to sift through the archives, I came across a fact here and

a riddle there that in eventual retrospect added up to a long series of small revelations.In Nabokov's diary for 1973, four years before he died, he recorded on January 28 that he had

begun to read the typescript of Field's biography, Nabokov: His Life in Part, for which Field wanted

feedback within a month. He began reading intensely, and by February 6 he noted: "Have corrected

285 pages of Field's 680 page work. The number of absurd errors, impossible statements, vulgarities

and inventions is appalling." The very day he made that exasperated entry in his diary, he began to

write Look at the Harlequins!. Still vexed months later, he wrote to his lawyer: "I cannot tell you how

upset I am by the whole matter. It was not worth living a far from negligible life . . . only to have a

blundering ass reinvent it."[1]In his mid-seventies, with perhaps not too many years to live, Nabokov felt that his life had been

betrayed. In reply, he served up a deliberately grotesque version of his life that would laugh any

unwitting travesty like Field's right out of court. He was painfully aware that this could well be the

last book he would ever write. The box of cards containing the manuscript of Look at the Harlequins!,

now in the

[22]

archive, has inside its lid Nabokov's instruction: 'To be destroyed unread if unfinished."

But even the knowledge that Nabokov feared this novel might be a parting shot that he might barely

have time to fire still did not redeem it for me. A novel apparently conceived in a spirit of urgent

exasperation and corrective contempt seemed no better than the narcissistic parody it had first appeared.

As I became more familiar with the archives, however, I came to discover more about Look at the Harlequins! The novel's opening, with its image of fate trying to bring two lovers together after not quite succeeding at first, strikes a keen reader of Nabokov as a distinct echo of the entire structure of The Gift. There Fyodor retrospectively construes what seem to him like repeated, inept moves by fate to bring Zina and himself together as proof that fate persisted until it found the right combination, as if convinced that only Zina would do for him.

That much could be gleaned without the help of the archive. I also discovered from interviews and elsewhere that Nabokov liked to tell others about the various ways fate had tried to introduce him to Véra before they were finally brought together, and that he insisted that even if there had been no revolution they would have somehow met.

In the archive, in a 1975 letter to his German publisher and friend, Heinrich Maria Ledig Rowohlt, Nabokov jokingly calls his new novel "Look at the Masks!"'[2] That nickname immediately coalesced in my mind with other facts I had amassed. I had asked Véra if she could tell me anything about her first meeting with Nabokov beyond the one detail he had dropped in an interview, that they met at an émigré

[23]

charity ball "No," she said, firm as a fortress. That did not stop me asking once more, and hearing the portcullis crash down again.[4] But Nabokov's sister Elena Sikorski told me that her brother had hinted to her that his poem "Vstrecha" ("The Meeting") reflected his first meeting with Véra.

I knew by then that every year in his late diaries Nabokov scribbled a word or two under May 8, and that one could deduce, by collocating all these entries, that he was reminding himself to buy Véra something to commemorate the day they met in 1923. One year, the diary reminder was simply the phrase: "profil’ volchiy,” "wolfs profile,"[5] a phrase from the poem "Vstrecha" that refers to a wolfs profile mask.[6] The woman in the poem wears a mask throughout, and seems to have stepped out from some masquerade into the starry night. The manuscript of this intensely romantic poem, also in the archive, shows that it was written three weeks after Nabokov and Véra first met. Elena Sikorski's explanation lies behind the summary I give in the biography of the event that lay behind the poem:

During the course of the ball, he encountered a woman in a black mask with a wolf’s profile.

She had never met him before, and knew him only through watching over the growth of his

poetic talent, in print and at public readings. She would not lower her mask, as if she rejected

the appeal of her looks and wished him instead to respond only to the force of her conversation.

He followed her out into the night air. Her name was Véra Evseevna Slonim.[7]

The moment I read that Nabokov had assigned Look at the Harlequins! the private nickname "Look at the Masks!" I realized that he was alluding to his

[24]

meeting with Véra; that the real title of the novel--also, with its imperative verb, an echo of Speak, Memory—was a private allusion to the Harlequin mask Véra wore when he first met her; and that in all likelihood the whole novel was a tribute to the kind fate that united them.

All sorts of hints in Look at the Harlequins! itself and throughout the archives pointed to the possibility that the novel might be not only an inversion of Nabokov's life and of Speak Memory, but specifically of his relationship to Véra. As I examined the novel once more, it became evident that each of the unlovable women Vadim marries was indeed in a different way a pointed inversion of certain of Véra's characteristics, while the 'You" who redeems his life distills in a few traits the essential Véra.

As I write in the biography, we see almost nothing of You, Vadim's fourth wife. She appears shortly before the end of the novel. Vadim describes the scene of their meeting.

As he emerges from his office at Quirn University, the string around a batch of his letters and

drafts breaks. Coming from the library along the same path. You crouches down to help him

collect his papers. "No, you don't," she says to a yellow sheet that threatens to glide away in

the wind. After helping Vadim to cram everything back into his folder she notices a yellow butterfly

settle on a clover head before it wheels away in the same wind. "Metamorphoza," she says, in her

“lovely elegant Russian.”

In this one short scene, she helps a writer assemble his papers [like Véra as typist, secretary, archivist];

she notices a butterfly [again like Véra, who in June 1941 caught a specimen of the hitherto

[25]

unknown species Nenonympha dorothea just as her husband was catching another a few hundred

yards below, inside the Grand Canyon]; she cannot help disclosing the alertness of her imagination:

she is Véra, putting two things together—a joke, an image—to make a triple harlequin. And then

Vadim terminates the scene to announce that reality would only be adulterated if he now "started to

narrate what you know, what I know, what nobody else knows [a pointed echo of Speak Memory's

"and presently nobody will know what you and I know”], [what shall never, never be ferreted out by

a matter-of-fact, father-of-muck, mucking biograffitist."][8]

Vadim has been appallingly frank about his other wives, down to their sexual peculiarities. But the moment he introduces You, he insists on privacy. That echo of Speak, Memory, that tribute to the real privacy of a real marriage, as opposed to the three marriages that have left Vadim's life so empty to this point, made me realise for the first time how decidedly Nabokov sees married love as one of the very rare partial escapes that life allows from the solitude of the soul. That escape, he suggests, can exist only where both partners can have absolute confidence that what they share with the other will go no further: only then can there be the kind of frankness, the kind of total sharing of the self, that elsewhere in mortal life is impossible.

Now I had long understood the importance to Nabokov's work of his frustration at what he calls "the solitary confinement of the soul. "[9] in life, he stresses, it is impossible to step outside the self and as if into another soul. The only way to achieve this is to step outside life, into the unique conditions of art, or

[26]

perhaps Into some state beyond the mortal self that the strange freedoms art allows somehow foreshadow.

What I now realized, after this succession of discoveries in the archive—and after having written more than two thousand pages on Nabokov—was that Nabokov was ready to define one other escape from the terms of our mortal imprisonment: not only in the unrealities of art, but in the reality of married love. That unexpected equation between art and married love became especially clear as I looked again at the bizarre marriage proposal Vadim makes to You. And here I cite myself, just the conclusion of the argument:

Until this last confession and proposal, through all of Vadim’s previous marriages, there has been no

connection whatever between his love and his art as a writer. Now during this [final proposal] scene,

for the first time in his life, these two parts of his existence come together, and in almost miraculous

fashion. The scene records a kind of ecstasy, a standing outside the self: knowing the depths of her

artistic responsiveness, Vadim, even as he walks away from her, can follow You's thoughts as she

reads over [the] index cards [of a passage he has just completed of his new novel, which he knows she

will take as both his own personal confession and his marriage proposal to her]. Art always allows for a kind

of transcendence of the self, as one person participates in the visions of another imagination, but here the

force of Vadim's love for You grants him a still more immediate transcendence of the self, a virtual entry into

her mind as she reads.At their highest, both art and the mental harmony of married love suggest to Nabokov a kind of

[27]

foretaste of what death may bring: the release of the self from its prison. [10]

Julian Moynahan once criticized Andrew Field's first and best book on Nabokov for arguing that Nabokov's works were all concerned primarily with art. That, Moynahan suggested, was a drastic diminution of their force. [11] For Moynahan, Nabokov was above all the great celebrator of married love. [12] if we look closely at Look at the Harlequins!, we can see the extent to which both are right, since there Nabokov links arts and married love as different means towards one of his central themes, the transcendence of the self.

A novel that appears compulsively self-referential turns out to focus on the transcendence of self; a novel that seems terminally narcissistic turns out to be a love-song, and no less passionate for all its play. And what especially interested me as a biographer was that Nabokov's career, dedicated unrelentingly to his art, and his life, devoted utterly to Véra, had begun to make a new sort of sense together.

By the time I had reached this conclusion—in the second-to-last of fifty chapters—I could finally appreciate the full measure of what the privacy of their married lives meant to the Nabokovs. By now, having solved the riddle of their first meeting, and Nabokov's sense of the difference that meeting made to his life and his art, I could afford to mind less than ever that Véra had so flatly refused to tell me how she and Nabokov had first met, or what happened next. There is a hole at the center of Nabokov’s biography, and there always will be; it is part of the romance of his story. Perhaps the hardest part of my task as a biographer was to find the right frame for that hole, the right knots for my net. And it was in the archive—

[28]

in a letter to Rowohlt, in a sequence of cryptic diary entries, in the manuscripts of a poem written in 1923 and a novel begun half a century later—that I found most of the strands I needed.

I returned to Montreux most recently in June, to help with the transfer of the archive. I have spent years there working on the manuscript materials, seeing Véra every day. Usually each time I return to the town, I am struck by the constancy of the place: the same familiar faces in the Grand-Rue, the same faces and furniture and food in the Montreux Palace Hotel. This time, I was struck by change. Véra was no more; the Palace Hotel, where she had lived for three decades, had just been radically renovated, and the Nabokovs' suite, and the small former linen room where I had sorted out the archive, had vanished. But now the manuscripts are here, in the city where Vladimir and Véra Nabokov arrived from Europe and at last found a new home, a haven from exile. Now, the archive that Véra began when she was not yet twenty and watched over until she was almost ninety has at last found its permanent home.

A coda now for Nabokov scholars: I noted in the course of the talk that although I spent just over two weeks working on the Library of Congress papers, and would have spent more time there had I needed it, I worked for almost two years on the Montreux papers that now belong to the Berg Collection. I estimate that the Berg archive contains almost ninety per cent of the Nabokov papers needed for his biography and bibliography, the Library of Congress archive about five per cent, and other collections about five per cent. These percentages will vary for different kinds of activity: for critical purposes, the Berg archive might occupy most researchers about eighty per cent of archival time; for editorial purposes, about fifty-five per cent.

[29]

The Berg Collection materials do not yet incorporate all of the papers that have been held in Montreux. Dmitri Nabokov has retained some that he needs for current business or future projects, but will send the material to New York as becomes feasible. Moreover, the materials will not be available for scholars until they are completely catalogued. Scholars eventually wishing to use the collection should contact Frank Mattson, curator of the Berg Collection (New York Public Library, Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street, New York, NY 10018).

_________________________

1. Letter to Joan Daly, May 28, 1973, VNA, cited in Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1991), p. 616.

2. Letter to Rowohlt, May 2, 1975, VNA.

3. Strong Opinions, 127.

4. Cf. The Russian Years, p. 558n.37.

5. 1969 diary, VNA.

6. ’Vstrecha," published Rul', June 24, 1923, repr. Vladimir Nabokov, Stikhi (Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1979), 106-07.

7. Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1990), pp. 206-07.

8. American Years, p. 633.

9. Conclusive Evidence (New York: Harper's, 1951), p. 217.

10. American Years, pp. 638.

11. Partisan Review (Summer 1968), 487.

12. "Lolita and Related Memories," Triquarterly, 17 (1970), 251.

[30]

NABOKOV AND THE MOSCOW STAGE: TWO EVENTS IN MOSCOW

by Brett Cooke and Alexander Grinyakin

Nabokov's return to the Soviet Union has now extended to his plays. Last year scenes from Invitation to a Beheading opened In the Teatr Ermolovy and the Edward Albee setting of Lolita was staged by the Teatr SFERA In Moscow. On May 26, 1991, the Theater on Malaya Bronnaya premiered its new production of The Event (Sobytie) under the direction of Arseny Sagal’chik, with sets by Mart Kitaev and Ekaterina Sokol’skaya’s costumes. Clearly The Event was greeted with some ambivalence. Sales fell far short of SRO status and, as we shall note, the direction was marked by much Indecision. Nevertheless, the results constituted an interesting reading of the long neglected play.

Throughout the production realism was mixed with the absurd. The unchanging set was, for the most part, a true to life room extending far back behind the proscenium, albeit walls were occasionally swung in so as to provide a different perspective. On the other hand, it was also littered with children's toys, including the balls mentioned in the text, and, as any Nabokovian must expect, butterflies, albeit with semi-nude women's bodies. For some reason a rope was hung over the front of the stage.

The stage action certainly did not lack for an interpretive point of view; it suffered, if anything, from a surfeit. Lines were delivered with emotion that

[31]

tended, as so often with Russian actors, to go to extremes. These expressed feelings, however, often clashed with the words spoken. Some of the absurdity seems motivated by the many references in the text to the theatre, etc., by now a device long since overused. Indeed, It is hardly fair to Nabokov's unjustly forgotten play that it reminds one of Beckett's Waiting for Godot, inasmuch as it was written and premiered in France long before that acknowledged classic.

Lyubov', played by L. S. Babchenko, laughs, kisses and plays with the large butterfly suspended over mid-stage as she speaks of her son's death. This in many ways accords with the play's ironic combination of the celebration of her mother's fiftieth birthday with memories of the tragic event. Her son would have been five years old the next day and, as a visual image of the enormity of the tragedy, a young child twice scampers across the stage, unnoticed by most of the players. In Sagal'chik’s vision, his parents and Ryovshin, Lyubov's lover, have internalized the child in their actions. Repeatedly they put on childish faces, make nonsense sounds, throw tantrums and strike absurd poses reminiscent for the American viewer of Tom Hanks in the movie Big. They also take turns sitting in the oversize chair at stage front right, looking somewhat like Lily Tomlin on the old TV program Laugh-In. Ryovskin (S. Y. Perelygin) delivers the seemingly fateful news of Barbashin's early release (here Nabokov has anticipated by some decades the present controversy over the role played by family members of the victim in parole hearings) while balancing on one leg. Lyubov', more than the others, again and again hops around the stage, clucking her tongue, like a child, no doubt her son, imagining a horse. These apparently unrelated fidgettings evince their latent nervous stress, their repressed memories of the event that was and, as the play develops, their vexed waiting for the event that is to be. But they are

[32]

too much. These devices not only distract and irritate the viewer, they also promote the image of Nabokov as an eccentric. Sagal’chik frequently drowns out the actors with violin music, the father’s (played by О. M. Vavilov) ”o-o-o-o" or a child's music box. Could it be that the director does not know what to do with the text? These gestures prolong an already long evening, three and a half hours in all.

Not surprisingly, the visual image of the Nabokov appears in the guise of Uncle Paul in the second act. The absurd now yields to the satirical portrait of Russian emigre life familiar to all Nabokovians. Dressed in a white suit with a maroon bowtie and wearing wire-rimmed glasses set at the end of his nose, D. D. Dorlian clearly cut a poshly double of the writer, especially with his exaggeratedly refined gestures and bent-knee dance at the end of his all-too-brief scene. Of course, that the master should be as ubiquitous as Alfred Hitchcock in stage productions of his works can only be laid to his own account, what with all the anagramic doubles who people his texts.

The second act constitutes on stage, as in Nabokov's play, a crescendo of poshlost' and it is, perhaps, a sad commentary on the contemporary state of Soviet mores that Russian actors handle this aspect of his oeuvre with much more ease than any other. Antonina Pavlovna's (A. V. Antonenko-Lukonina) reading of her Illumined Lakes ("Ozarennye ozera”) is particularly funny here. Besides her voice dying out, as in the stage directions, the Malaya Bronnaya team dims the lights and rocks the candles back and forth, back and forth ...

Although never abandoning the absurd and satire, the production turns more to Stanislavskian realism in the third act. G. Y. Martynyuk’s Barboshin the private detective is particularly memorable here.

[33]

Gestures and emotions now correspond as Lyubov' lists her husband's failing and as all await the forthcoming event that never comes forth. By now Sagal'chik shows his hand; he has reversed the text's progression from realism to farce via satire by contrary stage action the better, so it seems, to bring out relief in The Event.

The applaudismenty were hardly burnye ("stormy"). Nevertheless, one leaves this spectacle with the satisfaction of an often illuminating, though not entirely convincing reading of the play.

As for the other Event. Though announced on Moscow's streets and under our signatures in last Fall's The Nabokovian, we are still waiting for the Mayakovsky Theater's production of the same play to reach the boards.

[34]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

[Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov's works will be to the most recent hardcover U.S. editions.]

ANAGRAMS IN LOLITA

Nabokov's predilection for anagrams, particularly of his own name, is well known. These anagrams frequently contain important cultural subtexts, the discernment of which contributes to our better understanding of the authorial intent. Thus, in Lolita, which abounds with such anagrams, in the class roster (53-54), we come across the name of Viola Miranda—an anagram of Vladimir N. Mirando in Italian stands for "wonderful," and "viola miranda” therefore means "a wonderful viola.” This name of Lolita’s classmate may be seen as a reference to the wonder of art in general and to that of Lolita's creator in particular (cf. Nabokov’s referring to the gifted emigre poet Boris Poplavsky as "a far violin among near balalaikas," Speak, Memory 287 [or to his own Invitation to a Beheading as "a violin in a void”—CN]).

Nabokov employs a similar technique with the name of another of Lolita's classmates, Vivian McCrystal. As Gennady Barabtarlo has observed, ’Vivian” hints at Nabokov's initials, V. V. N.. and

[35]

"McCrystal" can perhaps be stretched to "magic, crystal," alluding to Pushkin's Eugene Onegin (Phantom of Fact 128) and to Nabokov's own creative art. The latter allusion is confirmed in the "Postscript to the Russian Edition of Lolita," where Nabokov speaks of "moem magicheskom kristalle, that is, ”my magic crystal" (Lolita, 1967, 299; for the English translation, see Nabokov's Fifth Arc 193).

Although Humbert Humbert imagines Viola Miranda as "of the blackheads and the bouncing bust" (55), this unappealing description is purposefully misleading. We may recall that Nabokov employs the same attention-distracting maneuver in Lolita on a number of occasions. Thus, Vanessa van Ness, whose name evidently contains an abbreviation of Nabokov’s first name, patronymic, and last name (WN), and twice the abbreviation of his first, last, and pen name (VNS), is twice described as "fat and powdered" (14). Also, the name of the playwright Vivian Damor-Blok (22), the Russian counterpart of Vivian Darkbloom (33), while presenting another anagram of the writer's name, echoes with "Damor" the Russian word morda ("snout" or "mug").

The "Russianized" name of this Lolita playwright and Ada scholar deserves closer attention. The second part of her hyphenated last name elucidates the allusion already surreptitiously present in the English original; it points, of course, to the Russian Symbolist poet Aleksandr Blok. The title of the play The Lady Who Loved Lightning (or in Russian, Dama, Liubivshaia Molniiu), which Vivian Damor-Blok co-authored with Clare Quilty, although contextually harking back to the circumstances of Humbert's mother's death, metatextually implies Blok's "Poems about a Beautiful Lady," the cycle he devoted to his wife, Liubov' Dmitrievna Mendeleeva. And the name "Damor" as well as the title-word "loved,” besides

[36]

suggesting that the cycle belongs to the genre of love poetry, both allude to Blok's wife, as her first name means "love" in Russian. "Damor" also contains the first letters—DM--of her patronymic and maiden surname and a partial anagram of the Russian word dama ("lady")—a title-word for the cycle and a keyword in Blok's poetry.

Additionally, "Damor," which reminds us of French d'amour and Italian d'amore, alludes to the other Liubov' in Blok's life, Liubov' Aleksandrovna Del'mas, with her French-sounding last name and Italian-related profession (she was an opera singer), the object of Blok's passionate love in the last decade of his life and, like his wife, an inspiration for his love poetry. Besides implying Del'mas's first name, her origin, and her profession, "Damor" is also a partial anagram of her last name as well as of the word dama, and contains her patronymic and last name initials. The allusion to Del’mas is of distinct import to Lolita, in which the Carmen theme is quite prominent. Although most of the Carmen allusions in Lolita are to Merimée's novella, Bizet's opera of the same name is not without significance there too (cf. Proffer, Keys to Lolita 45-51). In the fall of 1909 in Biarritz, the ten-year-old Nabokov met a French girl of nearly the same age, Claude Deprès—the Colette of his memoirs—with whom he intended to run away, perhaps to the mountains above Pau, after he had been inspired by Bizet's opera, recently heard, and particularly by Carmen singing "Làs-bas, la-bàs, dans la montagne" (Drugie berega 140; Nabokov's Dozen 49; Speak, Memory 150; Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years 78-79). Almost half a century later, this Biarritz experience served perhaps as a creative impulse for depicting Humbert's adolescent infatuation at the French Riviera with Annabel Leigh, Lolita's predecessor. The Blok-Del’mas association undoubtedly crossed Nabokov’s mind at the time of

[37]

writing this Lolita episode: in October of 1913, Blok first saw the singer in Bizet's Carmen in the title role, instantaneously fell in love with her, and devoted to her the poetic cycle so entitled, published the following year.

—Gavriel Shapiro, Cornell University

THE BANANA WAS A PINEAPPLE

In Speak, Memory (14, 2, page 283), Nabokov tells us that while in Berlin he "helped compile a Russian grammar for foreigners in which the first exercise began with the words Madam, ya doktor, vot banan (Madam, I am the doctor, here is a banana)." Brian Boyd drew my attention to the fact that this "grammar" probably was by one Jakow Trachtenberg. After some months' of search, I found a copy of the first edition (1927) in the municipal library of the Bavarian town of Augsburg. It may well be the only one that has survived the war. The title page reads: "Methode Trachtenberg. Lehrbuch der Russischen Sprache in der neuen Orthographie zum Selbstunterricht verfaßt von Russ. Akad. Ing. Jakow Trachtenberg unter Mitarbeit von Dr. phil. Fritz Goldberg. I. Teil. Verlag J. Trachtenberg, Berlin-Charlottenburg, Wilmersdorfer Str. 79.1927". So Jakow Trachtenberg, a Russian-German engineer, figures as publisher and author. He gives credit to a collaborator. Dr. phil. Fritz Goldberg, whose name, however, is absent from the subsequent editions (which otherwise contain only a few minor changes). In his short preface, Trachtenberg also expresses his gratitude to "the concert singer Miss Alice Bredow" for her "valuable advice in phonetic matters". In no edition is there any mention of Vladimir Nabokov.

[38]

The whole slight book is no grammar properly speaking but a text book for Germans wanting to teach themselves Russian, and quite a cranky one at that (Trachtenberg later derived a patented method of calculation which was published in America as late as 1960, I believe). The first four exercises explain the Russian alphabet. Exercises 5 through 11 contain nothing but alphabetical lists of Russian words which have similar sounding German counterparts, from "Abiturient" to "Zither", about 1.500 of them, which may be interesting linguistically, but probably of little help to beginners. The first short Russian sentences do not appear until exercise 12 (page 27). There the authors explain that in Russian the present tense of "to be" is often omitted, and as an example they have "Ich bin Doktor = ya doktor". And after giving the first 17 Russian words which don't have any similar sounding German equivalent, there comes a swarm of miniature sentences: "Gde kassa? Kto on? On moi doktor. Gdt tvoi direktor? Moi direktor tarn. Gde ananas?...." etc. No banana, though that had been listed among the words of exercise [9].

So Nabokov's memory faithfully reproduced the crankiness of the venture, but erred in the details. Trachtenberg’s course was no grammar. The foreigners were exclusively Germans. The sentences Nabokov quoted are not in the first exercise, but in exercise 12 (which, however, may be considered the first real exercise). 'Ya doktor" and the sentence about the fruit are not adjacent to each other. And the banana (which was not being proffered) was a pineapple.

THE GERMANS AT VYRA

During a visit to Vyra I was told by several people there that during the 900 days' German siege of

[39]

Leningrad (1941-1943) the Nabokov mansion had served as headquarters to "general Paulus" (I.e. field marshal Friedrich Paulus), the commander of the German forces at Stalingrad; and that the house was burnt down by the Germans when they hastily left. Valeriy Melnikov, however, who is in charge of the "Istoriko-literaturniy i memorialniy musei V.V.Nabokov" at Rozhdestveno, told me the latter part of the story is most certainly untrue, mere local lore comparable to the one that Vladimir Nabokov or his son had made their appearance in the region during the German occupation (in white uniforms, if I recall it right) and that the wooden house still was there after the war, empty and decrepit, and finally burnt down when children at play accidentally set fire to it.

The first part of the story I checked with the Bundesarchiv/Militararchiv in Freiburg, and I can report it is wrong as well. The German troops operating in the Leningrad region all belonged to the "Heeresgruppe Nord", the Northern Army, and Paulus never had anything to do with that. No German war diaries from that area are extant, but from a few army maps in the Freiburg archives it is clear that at Vyra a very minor detachment of the German army was quartered, "Nebeltruppen 3", whose job apparently was the spreading of smokescreens. The headquarters of general Lindemann, the commander of the 18th army which occupied this area (about 30 miles south of the ring around Leningrad) and one of whose main endeavours seems to have been the fight against Russian partisans, was at Druzhnoselie, about seven miles straight to the east, the former property of Prince Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg, a relative of the Nabokov family. Vladimir Vladimirovich had visited there repeatedly.

If the local rumours are correct in this instance, the German troops prior to their departure were

[40]

preparing to blow up the Rukavishnikov mansion at Rozhdestveno which Vladimir Vladimirovich had inherited shortly before the revolution and which now houses the Nabokov museum, but were prevented from doing so. The museum that was in the house when Nabokov was still taboo in his home country and that now is relegated to a few rooms mainly commemorates the time of the German occupation. There are maps showing the locations of numerous camps the Germans had set up in the area for Soviet prisoners of war and for civilians, most of them refugees from besieged Leningrad. After the war, many mass graves were found. At Rozhdestveno the Germans captured the Tartar poet and resistance fighter Musa Dzhalil who was executed in the Plötzensee prison of Berlin, where the Nazis also hung most of the conspirators of the failed 20th of July attempt on Hitler’s life. The title of Dzhalil's widely read prison notes, "The Moabit Notebook", inadvertently echoes the title of a book of poems by the German writer Albrecht Haushofer who was incarcerated and shot in the same place, "Moabiter Sonette”.

—Dieter Zimmer, Hamburg, Germany

DID LUZHIN HAVE CHESS FEVER?

In his weekly syndicated column, "Evans on Chess," Larry Evans drew attention on 24 March 1991 to a two-reel silent comedy from 1925, Chess Fever, directed by Vsevolod I. Pudovkin at the beginning of an important career as a Soviet film-maker: Mother came a year later. Chess Fever appears to have been constructed around an actual international chess tournament in Moscow, and incorporates footage of all twenty-one players, including the winning Bogolyupov, world champion Capablanca, Lasker,

[41]

Marshall, Tartakower, Torre, Reti, Gruenfeld, and Rubenstein. With that tournament as backdrop, Pudovkin's film told the story below, summarized here in Evans' words:

The hero is so obsessed with chess that his hat, scarf, sweater,

socks and tie are checkered in a black-and-white pattern. His shelves

are lined with chess books, and a board is always set up in his room

so he can compete against himself while eating or dressing.A note comes asking him to meet his fiancee at noon, but it is hard to

tear himself away from chess. Hurrying to her, he is lured into a chess

shop and plays another addict. When he finally arrives hours late, his

tearful fiancee curses chess as 'the greatest menace to a happy domestic life."He begs forgiveness by kneeling on his handkerchief, which is also

checkered, but begins a game on it with 32 pieces and a chess book

stashed in his coat. This is the last straw! She tosses the book from the

window and storms out, vowing to poison herself.Two cossacks in the street below retrieve the discarded book and promptly

use it to set up a position on their own board. A policeman, about to nab a

miscreant, instead starts a game when the rogue pulls out a pocket set.No longer able to tolerate the chess mania, she tries to buy poison in a pharmacy.

But the clerk, in the throes of a game, carelessly hands her a captured piece

instead of the fatal vial. On the way out she bumps into Capablanca and, not

recognizing him, stammers out that chess has made her hate life. "I understand

how you feel," he

[42]

says, gallantly disposing of the piece still in her hand. "I myself can't stand the

thought of chess when I'm with a lovely lady."Charmed and delighted, she gets in a taxi with Capablanca, unaware that he

is going to the tournament for a game. There she sees her swain, who is

despondent over losing her and has resolved to kill himself.She embraces him. "Darling, I never realized what a wonderful game this is!

Let’s play the Sicilian," she urges. They play chess and live happily ever after.

There seem to be many similarities here to The Defense, of which the most striking is not the obsession with chess but the decision to use an actual chess tournament as the background for a film. In the last chapter of The Defense Valentine announces his "brilliant idea":

I want to film a kind of real tournament, where real chess players would play

with my hero. Turati has already agreed, so has Moser. Now we need

Grandmaster Luzhin. ..

How frustrated he would have been had he found out that Pudovkin beat him to it!

-CN

EARLY BUCHAN, LATE NABOKOV

John Buchan is probably best remembered today for his novel The Thirty-nine Steps, made into a fine film by Alfred Hitchcock in 1935. But his most popular novels were published during and soon after

[43]

Nabokov's Cambridge years, and possibly formed part of N's extracurricular reading. Two curious items are listed below, but I make no great claims for them.

A few MacNabs

In a letter to Edmund Wilson, 24 November 1942, Nabokov listed a number of different people he had "collected" during a recent tour, including a college president who "has the students call him by his Christian name—and called me McNab because [he] could not pronounce it properly." Simon Karlinsky noted that "'McNab' is to be found in Nabokov’s last completed novel, Look at the Harlequins, as the nickname of the narrator-hero” (Nabokov/Wilson Letters 1980—the more accurate paperback edition— 88-89). As far as I can tell, this nickname bestowed on the narrator by Ivor Black was only mentioned twice, first in the novel's second chapter, as "McNab," and then in the second to last chapter as "MacNab" in the following passage:

Why had allusions to a Mr. Nabarro, a British politician, cropped up

among the clippings I received from England concerning the London

edition of A Kingdom by the Sea (lovely lilting title)? Why did Ivor call me

"MacNab"?

We should not overlook a possible reference here to Buchan's rather silly 1924 novel John MacNab, where three bored politicians all attempt minor daredeviltry under this nom de guerre. (Somehow, the major result of their group exploit under a borrowed name seems to be that they will be more sensitive Tories afterwards, i.e., better able to meet the challenges from the far left.) The theme is perhaps not altogether different from that of Vadim Vadimovich parading a sort of serial self for Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov. And

[44]

perhaps that college president had Buchan's novel in mind as well.

Another Pale Fire

At least as interesting is the 1922 Huntingtower, which features not just a Russian princess but "her dress, which was the tint of pale fire" on its first page. The plot involves smuggling the crown jewels out of a Scottish castle and into a local bank and then rescuing the princess from her Bolshevik captors. The rescue team (a retired grocer, a young poet, and some boys) is eventually joined by the man for whom the princess had been waiting ("a tall man with a yellow beard, who bears himself proudly"), the Russian nobleman Alexis Nicolaevitch who now goes under an Anglicized version of his name, Alexander Nicholson. Alex explains himself as follows:

For the present ... I am an Englishman, till my country comes again to her senses. Ten years ago I left Russia, for I was sick of the foolishness of my class and wanted a free life in a new world. . .. And now I have only one duty left, to save the Princess and take her with me to my new home till Russia is a nation once more.

I would guess that Nabokov read this Buchan novel (his British friends probably would have forced it on him), and that it should be listed alongside Anthony Hope's The Prisoner of Zenda as a colorful romantic fiction that influenced Kinbote's fantasies in a kind of half-forgotten way.

— CN

[45]

ADA’S PERCY DE PREY AS THE MARLBOROUGH MAN

by D. Barton Johnson

Percy de Prey is one of a trio of Ada's doomed lovers: limp music teacher Phillip Rack, robust Lt. Percy de Prey, and a bisexual actor named Johnny Starling. All have the good fortune to die (or be hopelessly maimed) before jealous Van can dispatch them. The present remarks focus on the unfortunate Percy and the motif complexes associated with him. The first centers on the French folk ditty "Malbrough s'en va-t-en guerre” whose tune (with different subject matter) is known in English as "For he's a jolly good fellow." The second, more obscure, motif complex involves cigarettes, presumably Marlboros. In what follows we shall treat the variant spellings Marlborough, Marlboro, Malbrough, and Malbrook as equivalent.

Percy is the son of Count and Praskovia de Prey who own an estate near Ardis (90 & 284). These de Preys are not to be confused with a second, kindred de Prey family: the late Major de Prey and his comedy actress widow. Their daughter, Cordula de Prey, (Percy's second cousin), becomes Van's on-and-off mistress. Percy, Van's schoolmate at Riverlane and three years his senior, is expelled in late 1884 after being caught in the rooms of "an ecletic prefect" with a lass disguised as a lad (168 & 190). By the second Ardis summer in 1888 Percy is already Ada's secret lover. Van's jealousy is fanned when Marina hints to Van, (and Praskovia de Prey to Demon) that Percy and Ada are involved (232 & 242).

[46]

Matters come to a head at Ada's birthday picnic on 21 July 1888 (I, 39). After Van and Ada have returned from a blissful sexual interlude overlooking Burnberry Brook (cf. Malbrook 266-67), Percy arrives uninvited and baits Van. Percy is no less jealous than Van since he knows of the cousins' love-making from his mistress Madelon, a servant at his mother's estate and sister of Blanche who works at Ardis Hall (335). As the picnic draws to a close, the young men amuse themselves at the brook by chucking pebbles at an old signboard. Percy then goads Van by displaying his oversized coeur de boeuf-shaped member, ostensibly to relieve himself. A brook-side scuffle ensues, and in parting, a duel is mentioned. On their trip home, however, Ada's love seems so total that Van's happiness leads "to the complete eclipse of the piercing and preying ache" that has troubled him (281, my underscoring—DBJ).

The next day Ada has gone to Ladore. Van lies reading when a messenger is brought to him: "a slender youth clad in black leather neck to ankle, chestnut curls escaping from under a visored cap" (283). The silent androgynous figure who echoes the lass-as-lad involved in Percy's expulsion from Riverlane later proves to be the younger sister of Blanche and Madelon (168 & 335). She bears a note informing Van that Percy is about to leave for combat duty and offering to assuage Van's honor, should he bear a grudge. Reassured of Ada's love, and content that his rival will soon be in the far-off Crimea, Van declines the opportunity (284). Dressing for dinner the next evening. Van finds an anonymous note in his pocket warning him he is a dupe (287). Going down, he finds Ada and Lucette copying orchid pictures while Blanche's voice is heard humming "'Malbrough' (...ne sait quand reviendra, ne sait quand reviendra) followed by the verse "Mon page, mon beau page, / — Mironton-mironton-mirontaine — / Mon page, mon

[47]

beau page..." (287-289). That night Van leams that Blanche has slipped the note in his pocket at the behest of her sister Madelon, Percy's jealous mistress (292-4 & 299). Confronted, Ada pleads that Percy means nothing to her, adding that "he left yesterday for some Greek or Turkish port" (296). As Van leaves Ardis forever, he learns from Blanche that Madelon, in order to avert a duel between the rivals, had put off her warning "until 'Malbrook’ s'en va ten guerre" (299). Percy is fatally shot in the first days of the Crimean campaign.

The text of Ada gives none of the "Malbrough" lyrics apart from those quoted above. These suffice to establish it as Percy's motif but other verses of the song also relate to the novel. We quote in full the first verse:

"Malbrook s'en va-t-en guerre,

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine,

Malbrook s'en va-t-en guerre,

Ne sait quand reviendra."

Subsequent verses follow the same pattern: the first line of each verse introduces the theme which is repeated in the third line; the second line is always the fixed rhythmical refrain "Mironton,...", while line four completes line one. In the following we give the first and fourth lines:

(1) Malbrouk s'en va-t-en guerre, / Ne sait quand reviendra.

(2) Il reviendra-t-a Pàques, / Ou à la Trinite.

(3) La Trinite se passe, / Malbrouk ne revient pas.

[48]

(4) Madam à sa tour monte, / Si haut qu'elle peut monter.

(5) Elle voit venir son page, / De noir habille.

(6) Beau page, ah mon beau page! / Quelles nouvelles apportez?

(7) Aux nouvelles que j'apporte, / Vos beaux yeux vont pleurer.

(8) Quittez vos habits roses, / Et vos sattins brochés.

(9) Mr. d'Malbrouk est mort, / Est mort et enterré.

(10) J' l'ai vu porter en terre, / Par quatre officiers.

(11) L'un portoit sa cuirasse, / L'autre son bouclier.

(12) L’un portoit son grand sabre, / L'autre ne portoit rien.

(13) A l'entour de sa tombe, / Rosmarins l’on planta.

(14) Sur la plus haute branche, / Le rossignol chanta.

(15) La cérémonie faite, / Chacun s'en fut coucher.

(16) Ainsi finit l'histoire, / De Malbrouk renomme.

The song (which some think dates back to the Crusades) is commonly thought to refer to the Duke of Marlborough (1650-1722), warrior, courtier, and diplomat, and his wife Sarah Jennings. The Duke, whose family name was Churchill, won a great victory over the forces of Louis XIV and lived to a ripe old age. Nonetheless, a surviving French soldier, perhaps in a fit of wishful thinking on the evening after the battle.

[49

supposedly made up the lyric of his death which quickly passed into popular use. Marie Antoinette overhead the Dauphin's wet nurse singing to the child and took up the song. The melody was soon used by Beaumarchais in his "Le Mariage de Figaro" and swept Europe following 1784. Goethe refers to it in his verse. Napoleon hummed it, setting off on his Russian campaign. Beethoven used it in his "Wellington Symphony and so on. ThroughzBeaumarchais' play, the tune became popular at the court of Catherine the Great and was performed at the funeral of her lover Prince Potemkin in 1791. It entered Russian popular usage as a wordless funeral dirge. Another folk version used a Russian translation of the French lyrics, but substituted the deceased Alexander I for "Marlborough." Still another version was reportedly obscene.

The most famous occurrence of the Malbrough song in Russian literature is in Tolstoy's War and Peace when Prince Andrei visits his father Prince Bolkonsky before leaving for the Napoleonic wars. As Andrey discusses the coming campaign, the old prince, distracted, begins to sing "Malbrook s’en va-t-en guerre. Dieu sait quand reviendra" (I, sections 23 & 24). Tolstoy places the song in Prince Bolkonsky's mouth to foreshadow the death of his son. "Malbrough" was known to nearly every member of the Russian gentry. In the years after the French Revolution even the most provincial Russian homes had émigré French nannies and tutors who must have taught the air to their young charges.

Nabokov chose "Malbrough" for Percy de Prey's motif for obvious reasons: its theme of the death of a lover in foreign battle. More specifically, jealous Blanche sings "Malbrough" to betray Percy to Van and, unwittingly, foreshadows Percy’s death. Apart from the "dead lover” theme, other fragments of the lyric

[50]

appear in Ada. Most important is the page who brings not the news of Percy's death, but the tentative duel challenge from Percy to Van. As in the song, the messenger is dressed in black (283). Another, more remote echo may be in Van's bitter reference to the maimed and mute Johnny Starling playing the page role of a "stable boy disguised as a kennel girl who brings a letter" in the play "Stambul, my Bubul" (381). The bulbul or nightingale may echo the nightingale singing over Malbrook's grave. These references would seem to exhaust Ada's direct allusions to "Malbrough s'en va-t-en guerre."

The second, more tenuous, motif complex identifies Percy de Prey with cigarettes, although he is never shown smoking. On two occasions Van smells Turkish tobacco on Ada after she has had secret rendevous with Percy (234 & 287). The key scene of the tobacco motif is the family dinner with Demon, Marina, Van, and Ada (260). Marina takes "an Albany from a crystal box of Turkish cigarettes tipped with red rose petal....” Ada and Demon also light up. Van then remarks: I think I'll take an Alibi—I mean an Albany—myself." To which Ada responds: "...how voulu that slip was! I like a smoke when I go mushrooming, but when I’m back, this horrid tease insists I smell of some romantic Turk or Albanian met in the woods."

The romantic Turk or Albanian is certainly Percy who is firmly identified with the Duke of Marlborough through the song motif discussed above. We would also note that Percy is persistently linked not only with tobacco, but with places with Turkish associations— Albania (Albany), Greece, Stambul, and the Crimea where he will meet his death. There is also perhaps a faint allusion to the Percy-Marlborough association in the cigarette brand "Albany" ('alibi') which shares its key letters "a", "l", and "b" as well as its dactyllic

[51]

shape with the manly Marlboro brand, presumably named in honor of the elegant and redoubtable Duke of Marlborough, who, like Lord Chesterfield and Sir Walter Raleigh, lent his name to the tobacco industry — as did the Duke's descendant Sir Winston, although he was a cigar rather than a cigarette smoker. It is via Sir Winston Churchill, the biographer of his illustrious ancestor, that Nabokov covertly supplies another indirect clue that supports the connection between Percy, smoking, and Marlboro's. In the paragraph before the dinner smoking scene, there is a remark about a translation howler by the British writer Richard Leonard Churchill in his novel about a certain Crimean Khan known as "A Great Good Man" (259). In his "Notes to Ada by Vivian Darkbloom” Nabokov witheringly identifies Winston (middle name Leonard—DBJ] Churchill as the source of the encomium to Stalin. The juxtaposition of the family name of the Marlboroughs and the introduction of the Albanys associated with Percy de Prey is probably not by chance.

Two objections to linking Ada's Albanies to Marlboros via Percy and the Duke may be advanced. The American cigarette brand is spelled differently and Ada's red rosepetal-tipped Albanies scarcely fit the image of manly Marlboro's. Both of these objections may be countered. According to Samuel Geng of Phillip Morris headquarters in New York, the Marlboro brand name was originally spelled "Marlborough," and was a red-tipped woman's cigarette. The red tips were to avoid showing lipstick traces. The poorly selling brand was discontinued before being repackaged and reintroduced in 1954 with its super macho image of the Marlboro Man. Although Nabokov had long before given up smoking, he could not have missed the massive Marlboro Man advertising of the fifties and sixties both here and in Switzerland. Ada, by the way, later seems to have

[52]

switched brands. In the debauche-a-trois scene we see at Van’s bedside a karavanchik of cigarettes and an ashtray (419). On the next page Ada opens the box (with its concealed "caro Van") and takes a Camel.

Ada contains still another association between smoking and the family name de Prey. This line of play involves not Percy, but his cousin Cordelia de Prey, Van’s mistress. Cordelia marries one Ivan G. Tobak, owner of an ocean liner, the Admiral Tobakoff named after his ancestor, the Russian Admiral for whom the Tobago or Tobakoff Islands were named five hundred years before. (On Terra, the islands were discovered by Columbus in 1498.) The fameux Admiral also fought a duel with Jean Nicot, the man who introduced tobacco into France. Lucette had secured last-minute passage on the liner by appealing to Cordelia de Prey-Tobakoff. The significance of this secondary tobacco motif is obscure, but is perhaps related to Lucette's suicide leap from the deck of the Admiral Tobakoff. Her drowning is foreshadowed in desultory conversation about the near-drowning Admiral Tobakoff (480). Prior to her fatal rejection by Van she has been smoking Rosepetal cigarettes (482). It is also Cordelia who owns an estate anagrammatically named "Malorukino" at Malbrook, Mayne (318, 458 & 499). For reasons that remain unclear to me both of the de Prey cousins seem linked to the Marlborough, Malbrough, Malbrook allusion complex.