Download PDF of Number 45 (Fall 2000) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 45 Fall 2000

_______________________________________

CONTENTS

News 3

by Stephen Jan Parker

In Memoriam - Elena Vladimirovna Sikorski 5

Dmitri Nabokov, Brian Boyd, Gennady Barabtarlo

“A View of a Room,” — Gennady Barabtarlo

“Babochki” (Butterflies), an excerpt 20

by Vladimir Nabokov

translated by Dmitri Nabokov

Notes and Brief Commentaries 21

by Gennady Barabtarlo

“The Expected Stress Did Not Come’: 22

A Note on ‘Father’s Butterflies’,”

Brian Boyd

‘“He Said - I Said’: An Afternote,” 29

Gennady Barabtarlo

“Six Notes to The Gift,” Yuri Leving 36

“Some Notes on the Variants in Pale Fire. 41

Part I” Anthony Fazio

“Wittgenstein Echoes in Transparent Things,” 48

Akiko Nakata

Annotations to Ada: 16. Part I Chapter 16 54

by Brian Boyd

1999 Nabokov Bibliography, Part I 77

by Stephen Jan Parker and Jonathan Perkins

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 45, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

- Brian Boyd’s “Annotations to Ada” (because superseded by, updated, hyperlinked and freely available on, his website AdaOnline).

In some but not all cases the downloadable pdf version of the print Nabokovian will have the annual bibliography and the “Annotations to Ada.”

[3]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

Because of a wealth of materials received for this issue, including an inordinately long annual bibliography for the centennial year, and because we cannot afford to print issues in excess of 96 pages, we will publish the 1999 annual bibliography in two parts. The first part (Bibliographies, Works, Books, Articles and Book Chapters) appears in this issue. The second part (Notes, Reviews, Dissertations, Miscellaneous) will appear in the Spring 2001 issue. In the interim, readers are encouraged to inform the editor of any omissions in the first part, which will then be included in the next installment. Similarly, because of space restrictions, this “News” section is exceedingly brief.

******

Nabokov Society News

The Society will as usual hold its annual meeting in conjunction with the national MLA and AATSEEL conventions, this year in Washington D.C., December 27-30. There will be two MLA panels at the Marriott Wardman Park Hotel. Panel I: 28 December, “Cross-Dressing: Nabokov as Novelist, Nabokov as Lepidopterist,” with Debra Lynne Walker presiding. The papers are by Brian Boyd, “Nabokov’s Butterflies: The Artistic Legacy”; Kurt Johnson and Steve Coates, “Recognizing Vladimir Nabokov’s Scientific Legacy”; Liana Ashenden, “Erotic Entomology in Ada.” Panel II: 30 December, Open Session, Charles Nicol presiding. The papers are by Dana Dragunoiu, “Cincinnatus C.’s ‘Gnostical Turpitude’ and A.A. Bogdanov’s ‘Socially Organized Experience’”; David Rutledge, “Nabokov’s Flaws: The Metaphysics of Mistakes”; David Galef, “Nabokov in Fat City.”

[4]

The AATSEEL panel will be on 29 December in the Capital Hilton Hotel, Galya Diment presiding. The papers are by Stephen Blackwell, “Nabokov’s Scientists in The Gift"-, Leonid Litvak, “Vladimir Nabokov’s Apprenticeship in André Gide’s ‘Science of Illumination’: From The Counterfeiters to The Gift”; Elena Rakhiimova-Sommers, “Nabokov’s Otherworldly Mermaid: “Spring in Fialta”; Natalia Lchtchenko, “Planes of Reality in Nabokov’s Pnin.” In addition, Anita Kondoyandi will present a paper, “Modem Exile and Spatial Form: Nabokov’s Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle” in the panel, “Literature in Exile.”

*****

Dmitri Nabokov informs us that the new film. The Luzhin Defense, successfully premiered at the Edinburgh Film Festival, and that on January 20 Milan’s Piccolo Teatro opens its season with a stage version of VN’s Lolita: A Screenplay, translated into Italian by Ugo Tessitore with Dmitri’s assistance. The director will be Luca Ronconi, assisted by Tesssitore. The play, “Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya,” with Dmitri Nabokov as VN and George Plimpton in the role of Edmund Wilson, was performed in New York at the American Museum of Natural History on November 30 and December 2 . The play will also be staged in Colorado at the Denver Cultural Center on March 2 or 3, along with a VN poetry reading.

*****

As always, our thanks to Ms. Paula Courtney for her irreplaceable assistance in the production of this publication.

[5]

IN MEMORIAM ELENA VLADIMIROVNA SIKORSKI

My dear Aunt Elena (Helene) Sikorski died on May 9. She had recently moved from her aging apartment in Geneva to a more comfortable environment, where she could keep her books, furniture, and other belongings, and yet have medical assistance if necessary. Moving old people is not always the best thing. In her case there may have been no connection, though: a full life has been lived and the time had come. There was no pain, no suffering, just a slight flu-like infection, and she died calmly in her sleep.

With the loss of my father’s beloved sister, the last direct link with a whole Nabokovian Russia vanished. Practically until her death I knew I could always call on Aunt Helena for particulars of family history and custom, linguistic nuances and many, many other details. She, too, with her multiple passions and her dedication to my father’s work, often telephoned me with some fascinating little story that she had suddenly recalled or some other fragment of filigree from the past. She continued, through the advancing years, to receive guests, to read, to follow events, hardly ever mentioning how hard everything was getting for her. She eventually resigned herself to the necessity of a walker, but only reluctantly accepted even part-time help. She was an adored and seemingly permanent presence. Even in her nineties she was beautiful, lucid and superbly telegenic. She even had my father’s eyes. But, alas, some of the most beautiful things are not permanent, and now I have no one to call for a special chat or a unique recollection.

For those who would like to know, Elena (Hélène) Sikorski is buried at Cimetière du Petit Saconnex, Tombe 238, Quartier AC.

Dmitri Nabokov

******

[6]

Nabokov’s sister, Elena Sikorski, died peacefully in her sleep on May 9. Born in 1906, the second youngest of the five children, she lived in St Petersburg, Yalta, London and Berlin, before moving with her mother to Prague in 1923. Married young to Peter Skulyari, she divorced and remarried again in 1932, to Vsevolod Sikorski, by whom she had one son, Vladimir, born in 1939. A librarian at the National University Library in Prague, she was able to extricate her family from Czechoslovakia by obtaining in 1947 a position as a UN librarian in Geneva, where she remained for the rest of her life. Her husband died there in 1958. Elena Sikorski is survived by her son (a simultaneous interpreter who has translated some of his uncle’s stories into French), her daughter-in-law and two grandsons.

One reason Nabokov found Montreux such a congenial place to stay after arriving there more or less by chance in 1961 was that it was only an hour away from his favorite sibling. They had become close for the first time in the Crimea, where Elena eagerly colored in her brother’s Belyan prosodic diagrams and acquired some of his zeal for butterflies, and they remained close in their émigré years. Readers of Selected Letters 1940-1977 (1989) can sense the warmth between them once they were able to reestablish relations across the Atlantic after World War II; naturally, there is still more conclusive evidence in Perepiska s sestroy (Correspondence with [my] sister, 1985).

VN and ES met for the first time in over twenty years in 1959, and after the Nabokovs settled in Europe in 1961, often visited and even holidayed together. Elena kept on the wall of her little Geneva apartment the framed original of the mock schedule that VN drew up for her on November 26 1967 when she came to “mind” him during Véra’s absence for a week in New York—perhaps the best sample of what Dmitri calls their “very special intellectual and ludic camaraderie.” This enchanting chart appears in print and facsimile in both Selected Letters and Perepiska s sestroy. Even if you have no Russian, you could do worse than sample the drolleries of the facsimile as a kind of tribute to writer and recipient and what they

[7]

shared.

In the 1970s, until her declining mobility made the trip impossible, Elena — the only one of V.D. Nabokov’s family ever to cross the Soviet border — began to revisit Russia every summer. Her first report back to Montreux HQ, in 1972, was vivid enough to inspire her brother with the plan of sending a fictional stooge to report on his return to the Soviet Union. Before her departure in 1973 Nabokov plied his sister with a checklist of details to look out for. A diligent and delighted spy, she collected just what he needed to impart an air of immediacy to Vadim Vadimych’s return to the Soviet Union in Look at the Harlequins!.

To Nabokovians from all over the world who wrote, rang, visited, interviewed, taped, filmed and generally pumped her, Elena Sikorski was unfailingly generous with her time and memories. She was open, informal and unguarded, warm and even fond, courageous and uncomplaining. I for one will miss her greatly.

Brian Boyd, May 30, 2000.

*****

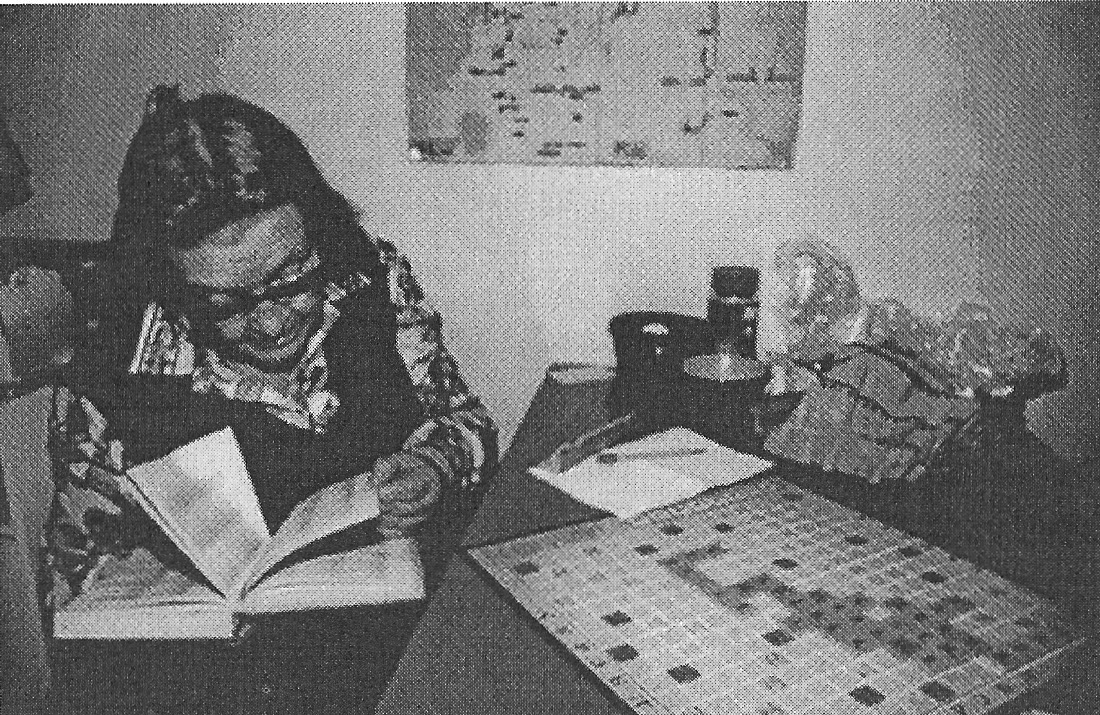

I want to add a few words to Brian Boyd’s obituary of Elena Vladimirovna Sikosrki, who was a close friend of our family. We visited her rather often, and exchanged letters, their number dwindling as she grew older and more reclusive. It is not well known that EVN was one of the best experts in her brother’s writings, having made independently numerous profound discoveries in the texts, some of which she gave to several acquaintances who sponged her for these things, while most remained in the margins of her copies of VN’s books (Ada’s first ed., for instance, is heavily covered with her remarks, some of which are absolutely first-rate, original and deep). Although she liked everything her brother wrote, she preferred his Russian books, especially Dar, and was cold to Lolita. She also knew much about his life that no one else did, but kept it to herself, along with a great number of private letters from him and about him. She was a

[8]

passionate and indefatigable Scrabble player, and every time I came to visit we would play several very interesting (rich, dramatic, often high-score) games, often clashing in disputes over the legitimacy of this or that Russian word (she stubbornly relied on a dreadful Soviet lexicon). In the end, the battlefield would be covered with crisscrossing words some of which formed curious thematic patterns (referring to something we talked about at tea earlier, or to VN, or to the probable future), and she would lapse into long thought over this, as she was half-convinced that that game was a little metaphysical in its implications. She was an Orthodox Christian of a very private variety. Her nameday will be this Saturday, the

[9]

3rd of June (Sts Constantine and Helen — to whom the Church in Tegel, Berlin, is dedicated; there, in the churchyard, her father was buried). Memory eternal.

Gennady Barabtarlo, 31 May 2000

A View of a Room

1.

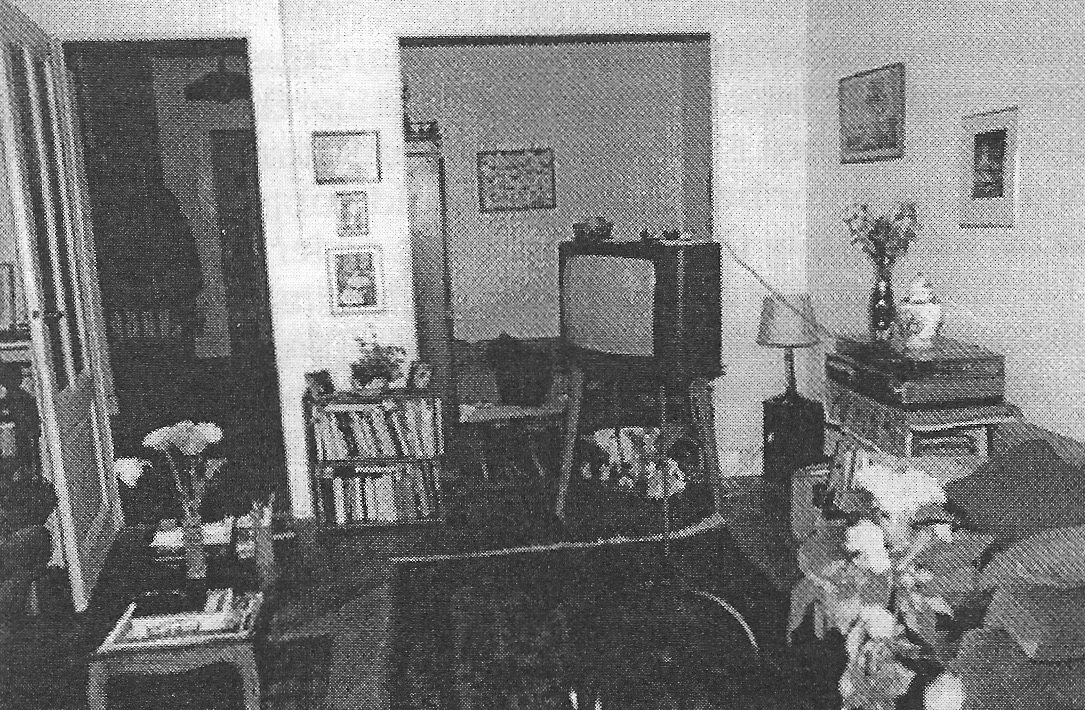

In the course of the last fifteen years she gradually reduced the range of her ever rarer outings and eventually confined herself to moving about her two-room flat in the belle-étage of an apartment building in the rue des Charmilles. She had acquired a habit of watching certain fixed items on the French television channels daily — at first it was mostly news programmes (at that time she wanted to believe, with many, that “Gorbachev could be Russia's savior”), then word-game shows of the Wheel-of-Fortune sort, and later some interminable sequential vaudevilles known in some Russian émigré circles as “mylodramas” (mylo = soap). Once or twice it happened that my visits interfered with the schedule, and she asked, slightly embarrassed, to excuse her for twenty minutes as she did not want to miss a turning installment (I was actually touched by this evidence of trust).

The large Italian window of her sitting room gave onto a green yard lined with smooth-trunked trees which separated the building from the street, and when I trudged from the train station, finding at length my way out of the maze of thwart lanes and carting my luggage up the rue des Charmilles, I would invariably see her from afar sitting at the window and waiting. That heart-warming ritual was rudely cancelled in 1989 when an ugly complex of office structures rose two stories high along the street hedging the view entirely. Now one had to turn from the street through an arched passageway and into the yard, its lawn now asphalted, its grey-barked hornbeams cut. Now we would see each other, usually after a long lapse, only at the threshold of her flat, in an abrupt, face-to-face moment of recognition and restora-

[10]

tion instead of the gradual approach, when one could waive from a distance and keep an inward smile aglow in advance.

We loved her dearly, which made it so easy to learn so much about her in such a short, cumulatively, time. Our cordial closeness was tested only once when, in a tactless letter, I could not refrain from warning her that one of her Soviet friends (several of whom took rather shameless advantage of her readiness to help, house, or carry a commission) could be of a darker shade of red than she might realize and thus not worthy of complete trust. Her keen sense of loyalty thus insulted, she answered in a stem tone of restrained indignation, snapping in passing at my blunder in interpreting a riddle in The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, which I had also made in that unlucky letter, and casually supplying a correct solution which at the time was not generally known. I saw the injury of my crude attempt at “protecting her” and apologized at once, and she was clearly relieved and glad to unpucker her brow, and the episode was never to be revisited. But I ascribed (not for the first time) its unexpected sharpness to an echo of certain exchanges on these and related topics that I knew she had had with her brother and sister-in-law after she had begun her regular trips to Leningrad. Often she tried to adopt, by discipline, an optimistic view of certain events in the USSR, but she remained troubled and uncertain on deeper, unexpressed, levels. When she saw no need to mount a defense against a possible assault on her hopeful view of the state of affairs there, she might remark, with a touch of sadness or mock disbelief on an instance of the disfigurement of her native language as used by one or another of her Soviet acquaintances, or of their crassness in judgement or manners, ill-compatible with her classical notion of the intelligentsia which they thought was their rightfully inherited station. Besides, some of the practical commissions they would give her every now and then were so cumbersome (to forward, to deliver, to arrange, to smuggle, to lodge, to accompany, to invite, even to sell), that, although her selfless loyalty to friends would always overcome the inconvenience, she did sometimes shrug in in bafflement, and at least once complained in my presence.

[11]

2.

Since we were both well-versed in the subtleties of VN’s logomancy, we soon became alerted, half-seriously, to the possibly non-accidental accretions of certain telling letters on one’s rack, suggestive words on the board, and even thematic pools, but carefully avoided pointing out such strings to one another, for fear of embarrassment. She especially was wary of any excess in spiritual matters and preferred tacit understanding (“O takikh veshchakh ne govoriat” — “one does not speak of such things”), having endured, out of sheer politeness, displays of gasping mysticism from some female admirers of VN visiting her from the USSR, who were given to sentimental spiritism and emotional indulgence. She firmly believed, along with most Russian people of her kind, now extinct, that emotions of the heart and mind, especially religious ones, ought to be kept in the privacy of one’s heart and mind, and that du mysterieux au ridicule il n’y a qu’un pas (or from “cosmic” to “comic,” in VN’s favorite version).

Once (in mid-March of 1989), she found herself looking at three Vs out of the seven tiles on her rack, visibly downcast, as this is not a very convivial combination in Scrabble. No sooner had she managed to place

[12]

or two of the V-tiles down (sighing in jest that place names are not allowed —Vevey would be helpful), than she fished out the fourth one from the soft-cotton sack. I do not remember who got the fifth (and last — the English version has only two V’s), but somewhere near that point she stared at the board, lapsed in thought, and since the fluctuation was now much too much to hold back, she raised her eyes at me and remarked in a stem, low, resolute voice that, say what I may [Kale khotite], but this could not be an accident.

She was a strong and dead-serious scrabbler, of a practical, non-romantic type, one who likes, of course, long and rare words and rich cross-engagements but who would go without hesitation or regret for an ugliest form, admissible only theoretically, if the move allowed her to score high, thwart a good move by her opponent, or simply get rid of ungainful or multiple letters (and she kept careful written record of high-value letters dealt to players during the game, mostly those from the bottom of the Russian alphabet). On earlier occasions I sometimes protested an especially flagrant instance, some highly questionable declension, “agami,” for example, the instrumental plural of “agha,” a Turkish officer — a form about as happy and permissible in Russian as “vividity” or “ands” (“no ifs, ands, or buts”) are in English; but she would never budge, coolly and quickly putting on her glasses and reaching for the terrible Soviet Ozhegov as her ultimate authority, and I would once again dismiss it as a sorry source, in the same words as two, and four, and six years previously, and we would engage in a give-and-take familiar to both, although the arguments had dwindled to a compact body from the initial tense dispute over the matter, now serving merely to remind one another of the transilience of time and the intransigence of our positions. And again I thought I could discern in her words and tone some distant echoes of her talks with VN and VE on things related to the subject at hand, as if she resumed with me a sharp conversation left off, years earlier, on the opposite end of the Lake.

[13]

3.

As it happens sometimes with long-standing relations which one surveys from a distance when they end, the first set of impressions was especially rich. When I visited EVN in August of 1981, she put me up in her sitting room, a bedsitter, really, as there was an iron-post bed in an alcove, under the display box with pinned butterflies which her late husband, rather than her brother (as one assumes at first), had collected. In those days she still ventured outside on occasion, and we took a taxi—a hippopotamian Impala, which looked especially huge and outlandish in Swiss traffic—to the department store, to her parish church (of the Russian Church Abroad), and to her son’s villa in the suburb. I never saw her as volubly frank about many things, general and private, as during those few days. It appeared as if, having once entrusted and deposited a load of treasured things, she later referred to them in passing or by hints, or more often not at all, simply assuming that they were safely stored. Of course, we both changed over the years that followed, and it is seldom easy to resume relations at the level once attained after two or three years of infrequent correspondence.

She lived alone, visited at times by her son; by her two grandsons of whom she was especially fond; by a woman

[14]

upstairs who moved in from Latin America in the late 1980s and who was hired to clean the flat and buy groceries (during my stays I liked to take that assignment upon myself, but EVN, who did not allow me to spend any of my money for her supplies, would subject the receipts to an amusingly thorough audit in order to repay me to the dime). She gave French lessons, gratis, to the woman’s son who had poor marks at school. Two or three ladies from her parish would come weekly, to play and chat. Later, as they, in turn, became home-bound, or died, she befriended a Soviet family attached to the UN who eventually managed to cast anchor in Geneva; they played Scrabble with her, and proved to be strong enough to keep her company for several years on end.

4.

Her knowledge and understanding of her brother’s writings were unsurpassed. She knew by heart a great number of his poems, but also a good deal of his prose, its seldom visited side-lanes and thoroughfares, Russian and English, and made important discoveries everywhere. She either committed them to memory, prodigious, agile, and undimmed to the end, or relegated them to the margins of her copies of VN’s books, almost all inscribed to her in the tenderest of words and fanciest of moths. In later years, she would reread a novel of his on a prompt by a correspondent from Leningrad or a scholar from Michigan, and give — in a private letter or conversation — a brilliant explication of a difficult spot where every visitor had tripped before. Sometimes she would ask me whether I agreed with this or that observation of hers, not really asking my opinion but rather making certain that I seconded hers, and as I almost invariably did (when it came to Nabokov’s writing, she was always right), she would say “But of course! It’s so obvious that one should wonder why no one has noticed that” (that, for instance, those twelve strangers keeping at a distance from a picnic are meant to be the Apostles). She received and read with care the ever rising heap of printed matter about VN that authors and publishers sent her more or less regularly, from the West as well as from the East. She answered

[15]

many queries, and once endured a series of dally sessions of listening patiently as I read aloud drafts of my translations of VN’s English short stories, and made some immensely useful corrections.

5.

Early in January of 1987 all three of us (my wife, our 11-year-old daughter) came to Geneva together and rented a vermilion Fiat Panda which proved to be a cheerful but ridiculously tight box. Struggling hilariously with its stiff manual gears and the unfamiliar layout of the traffic flow, I drove it on one occasion into the next lakeshore town and on another, to France, when all I wanted was to make a u-tuni and get to the center of Geneva, to her street. The black pavement was covered with patches of melting snow, but the air was wintry and had a tang to it, in a crisp northern way. The next day I felt if not confident then bold enough to take everybody to Montreux, with EV in the passenger seat. Wet snow was falling and slowly piling up, and I lost my way in Lausanne, where I slid back from every full stop at steep intersections before lurching forward, and the stout EV was uncomfortable in her old black frieze overcoat in her tight space, but we made it to the Palace in time for tea with VEN (it was her birthday). One could see that EV was not quite pleased with the visit, as on our way back, along dark roads faintly lit by the snow-piles swept up along the sides, she was silent and pensive.

The following day we took her to the cinema. It was near her place but she already could not walk even a short distance, and we again all packed into the Panda. I could not find a parking spot and let my passengers out at the theatre and continued circling the block. When at last I rejoined them inside, the film was already rolling somewhere in Rome or Florence, cast in persistent salad-green and creamy hues punctuated by wind-distressed red poppies, with occasional slow-motion flashes of gratuitous Lawrencian edited nudity, all wrapped in fruity music, sluggishly unfolding its sleepy, aromantic plot. One third into it she realized that the thing was not well suited for an 11 -year-old girl and cleared her throat every

[16]

now and then (the choice of the picture was hers). She saw that the film was pretentious folly but did not say it, making room for a differing view; instead, she repeated several times what a delight it was to hear the genuine and elegant English language spoken by the actors, which reminded her of the schoolmistress she had had in London in the early 1920s and which was so different from the vulgar American variety (she knew it from the comedies shown on her television). This theme led to VN’s English, about which she said with confidence that it was brilliant but audibly accented in an unmistakably Russian manner. Her own enunciation in every language she spoke was so uncannily like her brother’s that at times one wondered whether it was not affected.

That visit was the last one of its kind: after it, she would never leave the confines of her flat in my presence, nor would I have an advance glimpse of her sitting in the window as I approached No. 32.

6.

The very last time I saw her was nine months before she died (although the last time we spoke was on March 30, when I telephoned with usual greetings and she remarked that her 94th birthday was really the following day—a mistake that my wife, who keeps accurate mental tabs on dozens of birthdays, very rarely makes). During that visit we found her changed perceptibly. She had lost something that was not easy to name; it was a complex loss, to varying degrees, of keenness, attention, interest, and weight. The place had acquired a new faint smell of forlorn helplessness.

After the usual preliminary ritual of our putting the flowers we had brought in a vase under her precise directions followed by the tea-and-cheese ritual in the kitchen, she moved, inching forward, leaning heavily upon a quadruped walker but staring straight ahead, to the sitting room and onto the couch. She answered questions easily and exactly, without asking us to repeat them, but put uncharacteristically few questions herself. Then she told us that someone “from Russia” recently had asked her, in a letter or on the telephone, “whether

[17]

my brother was veruiushchii (a believer in God), and I said that he was but that he was not... well, religious (ne-religioznyi).” Sensing the difficulty, I ventured “ne-tserkovnyi?” The word rang right, as she apparently had been groping for it herself: “Yes, precisely, unchurched, yes. But he was veruiushchii, it’s obvious, isn’t it [ved’ eto iasno].” This question, which she had broached, warily, many times previously, seemed to occupy her mind now more than before.

Her memory, whether it was reaching near or far, was as sharp as always, and she seemed to hear and see better than ever. Yet nothing quickened her. She seemed dispirited in some very basic sense of the word. Her features had grown somewhat pinched, her irises faded, her pupils moved seldom and reluctantly; in fact, her eyes often seemed to be fixed at a very distant focal point.

They flashed a gambler’s spark, however, when her favorite pastime was proposed. It was a long and rather high-score affair. As luck would have it, I had most of the rich letters and some splendid ready-made formations on almost every rack, and so I had to brake hard in order not to run away - by abstaining, for instance, from chalking up 50 points out of a two-letter “IUT” (a quarter-deck) where the rare first letter would fall on a square and in a row that would increase its 8-point value six-fold. Soon into the game I became conscious of the fact that our crosswording was charting here and there a certain thematic line that began with “umolkla” (“she fell silent”, a full-rack, 50-point premium word) and ending with “vere” (the dative or locative case of “vera,” faith), with five or six words, all strangely related, in between. It was not unlike word-golf, but on a semantic level (“get to meaning X from meaning A in seven”). She took longer than usual to think over her moves, and, knowing that she previously always heeded such suggestive chain-links, I was trying to guess whether she had noticed the thematic persistence this time. One could not tell, as her eyes kept swiftly darting from her tiles to the board and back, but something in her expression, and an unaccountable sense that she had felt my gaze and understood its meaning, suggested that we were looking at the same

[18]

words with like thoughts. She won 422 to 406.

7.

She liked cut flowers, and when I did not forget I had them delivered to her on her nameday, and we always brought her carnations, or asters, or strange funnel-shaped daisies, each resting in its own cellophane ruff, from the local Co-op when we came over. On seeing me produce a bouquet from behind my back in the hallway she would flash a smile and say in her deep guttural voice “Kakaia prelist’!” (“How charming they are!”) and immediately order it into the same vase and onto the same spot on the low table by the couch.

She would not allow us to turn on the light at daytime, no matter how murky it could be in the room. Like her brother, she did not take the phenomenon of electricity for granted, and would invariably say on such occasions, “Let’s not burn Dostoevsky” - because in their childhood having electric light in daylight was considered a heart-pinching emblem of Dostoevsky’s artificial, indoor world where candles, or kerosene lamps, bum day and night and where even a third-floor apartment is underground. Like her brother, she thought Dostoevsky was a clumsy, unobservant mylodramatist.

Once we gave her a bunch of white carnations. She was touched as usual, but later, in an unrelated conversation, it transpired that she shared with some other Russians the vague notion that white flowers are proper for funerals - which she hastened to dismiss as silly superstition, so as not to embarrass us. Later in the day, while she and I were playing Scrabble in the kitchen, my wife and daughter went out and bought some carmine and cameo-pink carnations, mingled them with the white, discarding the white excess to keep the bouquet’s original size . When we returned to the sitting room and EV sank again onto the couch in front of the vase, she soon noticed the sudden polychromatization and for a while was genuinely stumped. Why should the white flowers suddenly blush and turn red? Her bewilderment went through several stages, and when at last she grasped what had happened, the look of feigned ironic

[19]

resignation that she took on (“I can’t believe it - what other trick will you pull next time?”) was very endearing.

After VEN’s death in 1991, she would say rather often, in half-serious tone, that she was perfectly healthy - had a healthy heart, no internal ailments, no usual marks of senilia, no physical deterioration, except for her joints (she suffered from degenerative osteoarthritis, and had her knees operated upon). She seemed at once amused and baffled by the thought that there might be no apparent “natural causes” for her death, and somehow I fell under the spell of that thought, and every time we bid farewell in the hallway, I gave a stock verbal assurance to her, and a less trivial mental one to myself, to see her again next time.

Gennady Barabtarlo

[20]

“BABOCHKI” (BUTTERFLIES), AN EXCERPT BY VLADIMIR NABOKOV translated by Dmitri Nabokov

A translated excerpt from VN’s poem “Babochki” (“Butterflies”) appears on page 121 of Nabokov’s Butterflies. As Dmitri Nabokov explains, “what appears in the book was a ‘filler’ version for the type setters....The correct version got lost in the shuffle.” Given below is that correct version, which will appear subsequently in the second printing of Nabokov’s Butterflies.

...From afar you can discern the swallowtail

from its sunny, tropic beauty:

along a grassy slope it dashes

and settles on a roadside dandelion.

My net swings, the muslin loudly rustles.

O, yellow demon, how you quiver!

I am afraid to tear its dentate little fringes

and its black, supremely slender tails.

Also, on occasion in the oriole-filled park,

some lucky mid-day, hot and windy.

I’d stand, ecstatic at the fragrance,

before a tall and fluffy lilac,

almost crimson in comparison

with the deep blue of the sky,

and, dangling from a cluster, palpitating,

the swallowtail, a gold-winged guest, grew tipsy,

while, blindingly, the wind was swaying

both butterfly and luscious cluster.

You aim, but the branches interfere;

you swing — but with a flash it vanishes,

and from the net turned inside out

tumble only severed crests of flowers.

©Copyright 2000 by the estate of Vladimir Nabokov

[21]

NOTES AND BRIEF COMMENTARIES

by Gennady Barabtarlo

[Submissions should be forwarded to Gennady Barabtarlo at 451 GCB University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, U.S.A., or by fax at (573) 884-8456, or by e-mail at gragb@showme.missouri.edu • Deadlines are April 1 and October 1 respectively for the Spring and Fall issues. • Most notes will be sent, anonymously, to at least one reader for review. • If accepted for publication, the piece may be subjected to slight technical corrections. Editorial interpolations are within brackets. • Authors who desire to read proof ought to state so at the time of submission. • Kindly refrain from footnotes; all citations and remarks should be put within the text. • References to Nabokov’s English or Englished works should be made either to the first American (or British) edition or to the Vintage collected series. • All Russian quotations must be transliterated and translated.]

* * *

It has been pointed out to me that the note by Ward Swinson on traces of Flatman in Pale Fire (Nabokovian, no. 44) fails to mention Brian Boyd’s 1998 article in Nabokov Studies (no. 4, p. 218, placed also on Internet’s Zembla) which treated the subject earlier, or indeed his new book on PF in which Flatman is discussed. The fault is mostly mine, as Professor Swinson had sent me his article before Boyd’s book came out, and I should have noticed the absence of reference (especially since I had read the book in manuscript.) My apologies to Brian Boyd. GB.

* * *

[22]

“THE EXPECTED STRESS DID NOT COME”: A NOTE ON “FATHER’S BUTTERFLIES”

With Dmitri Nabokov’s acquiescence, I supplied the title “Father’s Butterflies” for the most substantial piece of new fiction in Nabokov’s Butterflies. On his manuscript, [1] written at a time in 1939 when he was planning to carry the story of The Gift ahead in time and into a second volume, [2] Nabokov had penned the heading “Vtoroe dobavlenie k Daru”(“Second Addendum to The Gift”), adding“[pervoe: rasskaz ‘Krug’; eto zaglavie opustit’ i priamo nazvat’: ‘Pervoe dobavlenie’]” (“[first: story The Circle’; drop this title and call simply ‘First Addendum’]”). On the typescript, [3] where Véra had left a blank for the title, he added by hand: “Vtoroe prilozhenie k Daru” (“Second Appendix to The Gift’), adding: “(vkontsepervogo toma posle stoy glavy” (“[at the end of the first volume after the 5th chapter]”) which he crossed out and replaced with “(posle ‘Pervogo Prilozheniia’ v tom-zhe piatiglavnom Dare]” (“[after the ‘First Appendix’ in the same five-chapter Gift]”).

Robert Michael Pyle and I decided not to annotate “Father’s Butterflies” as we could have: why weigh down a pleasure craft on its maiden voyage with a heavy cargo of notes? Nabokov’s own attitude provided the cue: he always objected to footnotes in translations of his fiction, and in languages he knew, would try to incorporate explanatory glosses, wherever necessary, into the text itself. If he could not, he would prefer to leave the nuance uncaught rather than make the reader trip over notes at the foot of the page.

Those who have read “Father’s Butterflies” will have noticed that it is a difficult text, if also unprecedented and unusually rewarding. Many of its difficulties arise from its subject matter—Lepidoptera, taxonomy and evolutionary theory—and await explication from some impeccable and improbable scholar perfectly fluent in Russian and Nabokov and with an intricate knowledge of theories of speciation in the period between, say, 1890 (when Konstantin Godunov-Cherdynstev supposedly began publishing) and 1939 (when Vladimir Nabokov certainly

[23]

finished writing “Father’s Butterflies").

But there are other difficulties, much more easily explained, confronting the reader with no Russian. I want to provide a gloss on the end of the text (what can we call it apart from this neutral word: addendum, afterthought, appendix, asteroid, essay, fragment, meditation, memoir, outtake, précis, story?). For the first serial publication of the bulk of “Father’s Butterflies,” in the April 2000 Atlantic Monthly, I proposed to Dmitri Nabokov that we replace the word “accidental” in the closing passage in the book proofs, which by then were too late to change, with “by chance.” He accepted my reasons (rhythm, allusion and repetition), so I quote the emended version below.

Fyodor recalls a warm summer night when he, at fourteen, was reading on the veranda a book whose title he cannot recollect,

and my father, with someone—with a guest, or with his brother, I cannot make out clearly—was walking across the lawn, slowly, judging by their softly moving voices. At a certain moment, as he passed beneath an open window, his voice drew nearer. Almost as if he were reciting a monologue, for, in the darkness of the fragrant black past, I have lost track of his chance interlocutor, my father declared emphatically and cheerfully, “Yes, of course it was in vain that I said ‘by chance,’ and by chance that I said ‘in vain,’ for here I agree with the clergy, especially since, for all the plants and animals I have had occasion to encounter, it is an unquestionable and authentic. ...” The awaited final stress did not come. Laughing, the voice receded into the darkness—and now I have suddenly remembered the title of the book.

(Nabokov’s Butterflies 234, emended)

a moi otets s kem-to, s gostern ili so svoim bratom, ne mogu razobrat’, medlenno, sudia po tikho dvigavshimsia golosam, shel cherez ploshchadku sada, i v kakuiu-to minutu ego golos priblizilsia, prokhodia pod raskrytym oknom; i slovno proiznosia monolog, — potomu chto v temnote pakhuchego chernogo proshlogo

[24]

ia poterial ego sluchainogo sobesednika, moi otets vazhno i veselo vygovoril: “Da, konechno, naprasno skazal: sluchainyi, i sluchaino skazal: naprasnyi, ia tut zaodno s dukhouentsvom, tem bolee chto dlia vsekh rastenii izhivotnykh s kotorymi mne prikhodilos’ stalkivat’sia, eto bezuslovnyi i nastoiashchii ...” Ozhidaemogo udareniia ne posledovalo. Golos, smeias’, ushel v temnotu—no teper’ ia vdrug vspomnil zaglavie knigi.

(LCNA, Box 6, folder e, p.52)

As Alexander Dolinin notes, the whole of Dar, so steeped in Pushkin, can be seen as a reply to Pushkin’s famous 1828 lyric “Dar naprasnyi, dar sluchainyi, / zhizn’, zachem ty mne dana” (“Vain gift, chance gift, / life, why have you been given to me").[4] Here at the close of “Father’s Butterflies,” Count Godunov-Cherdynstev, a lover of Pushkin, echoes the poem (and, as we shall see, other Pushkiniana) in the sentence whose end Fyodor does not hear. The sentence opens “Da . . . naprasno," which strongly evokes Pushkin’s opening and suggests to a Russian ear that the closing ellipsis, as Grayson observes (p. 56), marks just a single word: “dar,” “gift,” as the Russian further confirms (dar is a masculine noun, and the adjectives bezuslovnyi and nastoiashchii, “unconditional, unquestionable” and “authentic,” are also masculine).

If the Pushkin echo does not completely fill in the blank for the Russian reader, the next sentence does: “Ozhidaemogo udareniia ne posledovalo,” literally ‘The expected stress did not follow. ” As Dolinin notes, udareniia, “stress,” itself includes the word dar (which, he also points out, is a motif throughout Dar itself),[5] and one could add that the syllabic “stress” of this word falls not on the syllable dar but on udarENiia, so that the “expected stress” on dar in Fyodor’s father’s sentence indeed fails to follow, even as Fyodor himself, in noting that very fact, follows with the missing word. The typically Nabokovian combination of overt negation and concealed affirmation, or of apparent refusal and actual grant, prefigures the last paragraph of The Vane Sisters,”

[25]

where the narrator’s lament that he can find no trace of Cynthia in his dream in fact spells out acrostically the role she and her dead sister have just played in his waking life, in his dream, and in the way he has phrased this very lament.

Here Count Godunov ends “Father’s Butterflies” by saying that he agrees with the clergy, and disagrees with the Pushkin of “Dar naprasnyi”: life is not a gift given “in vain” or “by chance”: instead, for the plants and animals he has encountered, it is an unquestionable and authentic gift. He “agrees with the clergy,” in pointed allusion, as Gene Barabtarlo notes (personal communication), to a well-known exchange between Pushkin and Philaret, the Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomna, the most prominent hierarch of the Russian Church. "Dar naprasny” appeared in print in December 1829 (in Severnyia Tsvety for 1830). In early January 1830 Pushkin's friend Elizaveta Mikhailovna Khitrovo, an admirer of Metropolitan Philaret, sent to Pushkin the Metropolitan’s rejoinder to his poem, which began

Ne naprasno, ne sluchaino Not in vain, not by chance

Zhizn’ ot Boga mne dana, Was life given me by God,

Ne bez voli Boga tainoy And not without God’s mysterious will

I na kazn’ osuzhdena . . . Is it condemned to death . . .

On January 19, 1830, Pushkin in turn replied, in a spirit of retrospective reflection, retraction and respect, in the lyric “V chasy zabav il’ prazdnoi skuki' (“In hours of diversion or idle boredom”).

If Dolinin is correct, as he surely is, that Fyodor’s Dar is a reply to Pushkin’s “Dar naprasnyi, dar sluchainyi,” then Fyodor’s addendum to his novel ends with his father’s echoing and agreeing with Metropolitan Philaret’s much briefer reply to Pushkin’s poem. Count Godunov evokes Pushkin, and concurs with the clergyman that life is not a gift given in vain or by chance. But the word “gift” itself is withheld, it disappears, as Count Godunov himself will disappear somewhere in Centred Asia. Yet

[26]

Fyodor’s father’s very disappearance, such a tragedy for Fyodor himself, enough indeed to make him feel at times that life is a gift given in vain or by chance, turns out to be the subject and the source of inspiration for his greatest work, The Gift [6] while Pushkin, somewhere behind Fyodor’s father, proves to be a still more remote subject and source: [7] not just a source of literary inspiration, as in D. Barton Johnson’s Worlds in Regression, 99-101, but an active presence in Fyodor’s life.

Which still does not answer the question: what is the title of the book that Fyodor was reading at fourteen and now suddenly remembers? If it is not quite Dar itself, that title, that word, stands insistently before us, once again, even in its absence, just as so much (Berlin, a new rented room, the public transit system, this frustration, that failure) that seems “ungifted” (bezdarnyi) in the novel proves to mark not the absence of a gift but the presence of a covert and vastly more generous gift than Fyodor could ever have had reason to expect.

Pushkin wrote “Dar naprasnyi, dar shichainyi,” then retracted its disenchanted mood in “V chasy zabav il’ prazdnoi skuki.” Konstantin Godunov, walking in the fragrant darkness across the lawn, must have at some point echoed Pushkin’s line or mood, before retracting it, as he now “declared emphatically and cheerfully,”—as if, indeed, he is playfully speaking for Pushkin [8], or Pushkin is speaking through him—“ ‘Yes, of course it was in vain that I said “by chance,” and by chance that I said “in vain.’” The overlap of the voices of Pushkin and of Konstantin Godunov is much stronger in the Russian than it can be in the English. “Da, konechno, naprasno skazal: sluchainyi, i sluchaino skazal: naprasnyi” could quite legitimately be construed as “Yes, of course it was in vain that he [Pushkin] said ‘by chance,’ and by chance said ‘in vain,”’ since of course Pushkin did say those words, and since the subject of the verb is left understood (as often in Russian) and Russian past tense inflections indicate number and gender but not first, second or third person. Only the seamless continuation of the sentence into “here I agree with the clergy” might seem to suggest that Godunov as “I,” rather than Pushkin as “he,” is the

[27]

subject of “said,” although Pushkin himself in “V chasy zabav i prazdnoi skuki” of course also says in effect that he agrees with the clergy, and it is not really until the continuation, “especially since, for all the plants and animals I have had occasion to encounter, ...” that we can be more or less sure that the “I” refers more or less unequivocally to the naturalist and explorer Godunov than to Pushkin.

The grammatical blurring is no accident. In Chapter 2 of The Gift, Fyodor, preparing to write the life of his father, to switch from poetry to prose, saturates himself in Pushkin, especially his prose:

he fed on Pushkin, inhaled Pushkin (the reader of Pushkin has the capacity of his lungs enlarged). He studied the accuracy of the words and the absolute purity of their conjunction. . . . Pushkin entered his blood. With Pushkin’s voice merged the voice of his father. . . .

(The Gift [New York: Vintage, 1991], 97-98)

Here, in “Father’s Butterflies,” Nabokov makes Pushkin’s voice merge, more closely than ever in The Gift itself, with the voice of Fyodor’s father, and it does so at the very moment where Pushkin, and then Fyodor’s father, seem to retract the idea that life is a gift given in vain and by chance. And through the gifts that both Pushkin and his father bestow on him, Fyodor can overcome the frustration he has felt at his emigre existence, and retract that frustration in a spirit of gratitude and affirmation, in his Dar, his Gift.

One final observation: Dolinin notes that the da (“yes”) in dar and blagodamost’ (gratitude) “begins to sound like a ‘Yes’ addressed to the world and its creator” (and he notes, too, that Nabokov appears to have once intended to call the novel Da rather than Dar).[9] Fyodor’s father’s last word in “Father’s Butterflies,” the missing “dar,” ends a sentence that begins with “Da.” I began my discussion of The Gift in VNRY by pointing out the way the whole subject and scale of the novel seem a reply and homage to Ulysses, and later note other ways in which

[28]

Nabokov seems deliberately to echo Joyce, not least in that “like Ulysses, The Gift .... traces a son’s special search for his father and in fact makes the relationship between father and son a kind of metaphysical riddle.” [10] In 1933, the very year he began The Gift, Nabokov had offered to translate Ulysses into Russian. [11] Now he has “Father’s Butterflies” draw to an end with the resonant affirmation that begins with Fyodor’s father’s apparently casual “Da ...” and ends with an unheard “dar" that together not only evoke Pushkin but seem also to echo Molly’s great “and yes I said yes I will Yes” at the end of Ulysses.

1. LCNA, Box 6, folder e.

2. See VNRY 505-06, 526-17, and Jane Grayson, “Washington’s Gift: Materials Pertaining to Nabokov’s Gift in the Library of Congress,” Nabokov Studies 1 [1994], 21-67.

3. LCNA, Box 6, folder f. The typescript consists of only the first 5 pages.

4. “The Gift,” in Vladimir E. Alexandrov, ed., The Garland Companion to Vladimir Nabokov (New York: Garland, 1995), p. 166, n. 29.

5.“Tri zametki o romane Vladimira Nabokova Dar” (“Three notes on Vladimir Nabokov’s The Gift’), in B. Averin, M. Malikova and T. Smirnova, eds,. V.V. Nabokov: Pro et Contra (St. Petersburg: Russkii Gumanitamyi Institut, 1997), 697-740, pp. 598-99n.

6. As I argue in VNRY, ch. 20.

7. As I argue in “Nabokov, Pushkin, Shakespeare: Genius, Generosity and Gratitude in The Gift and Pale Fire,” New Zealand Slavonic Journal 1999:1-21.

8. If, as the passage suggests, his interlocutor is his brother, the chance of a playful impersonation of Pushkin becomes high. Fyodor describes his father’s and his uncle’s “numberless and deliberately grotesque dialogues, ” and provides a sample, full of exuberant role play (Gift, Vintage edition, 130).

9. “Tri zametki,” 703 and n.

[29]

10. VNRY 447, 466.

11. Nabokov to Joyce, November 9, 1933, and to Paul Léon, 29 November 1933 and January 6, 1934, James Joyce-Paul Léon Papers, National Library of Ireland.

—Brian Boyd, University of Auckland

“HE SAID - I SAID”: AN AFTERNOTE

Publication of a note is often preceded by a flurry of letters between the patient author and the pedantic editor, especially now that ephemeral mail invites previously unimagined excesses in verbosity. Sometimes this bloated correspondence is useful, however, especially when one steps in a gainfully unresolved disagreement, as in the dialogue below. The original exchange with Brian Boyd over his note spanned almost the entire month of September and is at least twice as large, but I have extracted from it only the arguments concerning two items, the “he said - I said” controversy, and the title of the book that Fyodor recaptures but does not impart.

GB: "I said” ... “I said” (on the second page and next to last). This is a serious mistake which I missed on first reading, for, while the Russian past tense indeed agrees with any person, “skazal” here is most certainly the 3rd, i.e. “he, Pushkin, said by chance etc.” — they had somehow brought up Pushkin in their conversation, and here KG [Konstantin Godunov] refers to him — the other possibility is really much less plausible. P. is not “speaking through him”, but he had been speaking of Pushkin a moment earlier. I am quite certain that the correct translation is “he said”, with direct reference to P. Concerning the title of the book FG [Fyodor Godunov] was “reading.” I can offer two possible solutions.

1. FG does not say that the missing word was in the title, only that it triggered and closed the memory circuit. It could be thus a book of Pushkin’s verse. Else, the book could be unrelated to Pushkin but the word “dar” could be embedded in the name of the author - the best

[30]

candidate I know would be an excellent book by Darski “Chudesnye vymysly (v lirike Tiutcheva) - “Wondrous Fantasies”, which would fit on all sides (it was published in 1914).

2. This passage can be understood in a totally different vein: it’s not so much the boy reading the book whose title he cannot at first recall 25 years later and then of a sudden does (like the retrieval of Floss), but rather an attempt to “remember” the titles of the books, or rather the very book one is now reading, that the boy was about to write - a reverse perspective of a mnemonic effort, which VN tried to describe in “Guide to Berlin”, ‘Time and Ebb”, and, finally, in LATH (also in Ada, in a warped way).

On further musing, I see that that “skazal” cannot be rendered idiomatically in the first person at all, as it would require the personal pronoun (in a dialogue.) “On” is not necessary, although the phrase would sound more natural with it. But then VN probably wanted to withhold a hint that would be too revealing. “I said” is then a certain mistranslation; indeed, the right one is not even “he said” but .’’..he says” (in the sense “..Pushkin writes”).

BB: I am not convinced about“skazal,”despite your second note on the subject. Wouldn’t it be conceivable that he could say this in the sense of“ia skazal” if his brother, say, had just said to him:“A ty pomnish’, kak ty odnazhdi skazal, chto ty soglasen s Pushkinym, chto zhizn’ — dar naprasnyi i sluchainyi. Po-moemu, ty skazal eto sovsem naprasno.” (Do you remember saying once that you agree with Pushkin that life is a vain and chance gift? I think you were quite wrong (lit. “you said it quite in vain”)]. I’m not saying the brother would have been so dull, but I just want to establish that some cue from his interlocutor could have led Godunov naturally enough to drop a first-person pronoun. Which of course does not at all rule out that Nabokov wanted the ambiguity of the uncertain grammatical subject there.

If one considers the first half of the sentence, up to “naprasnyi,” then indeed it would be more natural to read it as third person, but if one considers the second half, it seems more likely that it is not. The “ia tut zaodno” flows

[31]

seamlessly from what has preceded (and could be either KG echoing Pushkin, as he could have been doing from the start of the sentence, or speaking in his own voice) and into “mne prikhodilos”’ (which is certainly talking about the plants and animals KG and not P. encountered). If in “skazal” Godunov is speaking for Pushkin, this would make it an implicit “(ia) skazal” again, of course, although with a different implied “ia”; but if he’s speaking of Pushkin in the third person, wouldn’t it then be natural and almost necessary before “ia tut zaodno” to mark the transition from Pushkin to Godunov himself as grammatical subject with a conjunction like “no” [“Öand yet”]?

GB: Not wishing this point, important as it is, to grow into a VN-EW 1942 polemics on metrics, I will say again that the main argument against “I said” is that it is quite impossible to say it in idiomatic Russian (in that context). It’s a relatively subtle impossibility, for no grammar rules of the language are broken or bent, only those of usage (in a dialogue) — but then definitely so. I am quite sure that VN could not mean it that way, as it would require precisely the sort of blunder that marked for him inferior writing in others. Don't try it on the first Russophone you find, since this experiment requires explanation by another Russian.

To give a very approximate, but meaningful analogy in English: There is nothing grammatically wrong about writing “I’ve understood”, in reply to a precedent statement, in a written dialogue, instead of the idiomatic “I understand” or simply “Understood.” But wouldn’t you say that it’s a mark of a foreign accent?

“Skazal” in this context without the “ia” is possible only in poetry, not in prose.

As for the plausible antecedent scenarii, I don’t see why we should complicate the conversation as much as you suggest. KG’s entire monologue is a negation of Pushkin’s dictum. Let’s say that that nocturnal exchange was about the mystery and purpose of life. The second person might have said, — “Yes, but you remember what Pushkin said of it: Dar naprasnyi, dar sluchainyi ... Was he not right?” to which KG replies that yes of course

[32]

Pushkin was wrong on both adjectives, I find myself in agreement here with the clergy, — and produces his elegant lexical spoonerism: P. should not have said (=naprasno) “by chance,” and it was without giving it much thought (=sluchaino) that he said “vain”, for KG’s own experience as a naturalist has convinced him that the gift of life is neither vain, nor chance, but unconditional and genuine.

In this plain sequence no oppositionary “and yet” is necessary.

But the main argument against “I said” remains its stylistic impossibility.

BB: Your comments have prompted me once more to add almost as much again to “The Expected Stress”.

Imenno kto skazal? [Exactly who said that] I remain unconvinced so far by your assertion that it cannot be “ia”. You don’t dispute, from what I can see, the possibility of my antecedent scenario leading into the phrase as cited, and that’s all I ask for: a recognition that it could be taken that way, even if the other sense ([on] skazal) might seem more likely. And in fact “I’ve understood” in English is perfectly possible, in various combinations of context and nuance and intonation, although it is of course less usual than “I understand.” Of course I realize that a native speaker cannot always explain to a visitor just why something won’t work, even if it is definitely wrong. But I think I have found a solution that synthesizes, I hope elegantly, my thesis and your antithesis.

GB: You are defending a lost cause here, building a complex of a double negation where none is meant or necessary, and where the meaning is plain. While reading your latest version, I noticed that you don’t seem to be concerned by KG’s “Da, konechno” and even try to use it as a support for your strudture, whereas it’s a wrecking ball. If it had been KG who said “dar naprasnyi” then, retracting it now, he would have to say Net, konechno, naprasno ia skazal (actually, the idiomatic way would be to use another opposition, “on the other hand”: “Vprochem, naprasno ia skazal). Not “yes” but “no” - which function differently in English and Russian in some situations. And, on the other hand, even if KG’s “echoed Pushkin’s

[33]

line or mood” (he could not do the latter without invoking the former), why would he ascribe the utterance to himself in order to gainsay it? would he not rather refer to the original author of the line and the mood? The whole monologue, while very significant, is not really as elaborate and deep as you present it.

But really, the Russian usage is what seals it after all is said. Well, have it your way, but I may have to insert, with your leave, a note of disagreement.

BB: If there is any conceivable scenario that could lead to “Da, konechno, naprasno skazal” meaning “I said,” then that’s all that my argument requires, and my admittedly gracless or worse “Apomnish", kakty odnazhdy skazal, chto ty soglasen s Pushkinym, chto zhizn’ — dar naprasnyi i sluchainyi. Po-moemu, ty skazal eto sovsem naprasno” doesn’t seem to have been ruled out by you. Surely that doesn’t require a “net” (or “vprochem”) in response? And one could easily retract one’s own articulation of a former “dar naprasnyi” mood without at all thinking that Pushkin wrote those wonderful lines “naprasno” and “sluchaino.”

GB: Your imaginary gambit to KG’s playful utterance is perfectly idiomatic. I would only remove, ironically, the second “ty” which is superfluous. It appears to be a plausible prelude to the “I said” interpretation. With it, my objection changes shade from the “English vermilion” to coral or even cherry. Two points here:

1. In your clever scenario, it would be more natural, almost compulsory, for KG to pin a reference onto the earlier conversation, e.g. “naprasno ia togda skazal sluchainyi” and, especially since he then was soglasen s Pushkinym [agreed with P. [but now, “s dukhovenstvom” [the clergy] - he would have said “no teper” ia soglasen s dukhovenstvom”, to account for a complete about-face. By the way, should not that diametrical change of view strike one as strange? Is there anything in the character of KG that allows for such swings? In fact, the opposite seems true: Fyodor’s father, as described, is a constant (I am not implying by this that that determined the choice of name). And so is VDN in SM. You see an improbably even line, a character of strong and unalterable convic-

[34]

tions, acquired some time before the son’s birth, and certainly one that does not change his views on such important subjects as life’s purpose, let alone so radically and so casually. And why should a man who has observed so many creatures flowering and fluttering and uses this as an argument for life being a true gift not consider the same experience earlier when he had said to the same interlocutor that life had no purpose? (I presume you do not suppose that that earlier conversation took place decades earlier, before KG began his studies). VN surely must have had some version of the immediately preceding exchange in mind; if so, could he make Fyodor depict his father, who shared with VDN an important trait — a deeply-seated, contemplative secret knowledge, or belief, one that even his closest could not fathom, — I say, could such a man be made to think — and say openly! — that life had no purpose without upsetting the entire outline of his character?

But the main thing is that

2. given the relative artificiality of your model and the perfect naturalness of the version “Here I disagree with Pushkin and agree with Philaret: if nothing else, my natural science tells me that life is a true and meaningful gift”; given that this artificiality is compounded by an unusual, almost “poetic”, Russian usage; given, finally, that your version hasn’t even one of the expected temporal markers “then/now” in reference to the antecedent — I ask you, what should a translator, who in English must choose one version over the other because his medium admits of no ambiguity here, prefer and thereby seal as decisive, “I said” or “he said”?

Another reasonable, if amusing, possibility for the suddenly remembered title has occurred to me. Since the word “dar” is a mnemo-homo-phonic trigger (which is prefigured in the preceding “udarenie” [stress], as you and Dolinin say), it can launch an association indirectly, e.g. through the author’s name. I suggested Darskii’s “Wondrous Fantasies” of 1914, but would not a DARwin suit the subject of the addendum better? For instance, The Origin of Species from “Bookcase VIII” (cat. no. 2287,

[35]

published in “New-Jork”, sic) or even L'expression des èmotions chez l’homme et les animaux, Paris 1877, from Case IX (no.2268)? A young poet expects but does not get to hear the word “dar”, then drops his eyes on the book in his lap and smiles at the gratuitous overlap — and then 20 years later remembers his smile and the title of the book he was reading then— and the title of the book he is finishing now alights on his shoulder, just as “Pale Fire” would on Shade’s.

BB: I like DARwin! A gift, a win. It would be a very Nabokovian solution (and remember the Darwin at the end of Podvig [Glory] nicely identified by Charles N as Charles D). And re your “A young poet. . . drops his eyes on the book in his lap” etc: also Nabokovian and reminds me of Ada II.9:

“Finestra, sestra,” said Van, mimicking a mad prompter.

“Irina (sobbing): ‘Where, where has it all gone? Oh, dear, oh, dear! All is forgotten, forgotten, muddled up in my head—I don’t remember the Italian for “ceiling" or, say, “window.”

“No, ‘window’ comes first in that speech,” said Van, “because she looks around, and then up; in the natural movement of thought.”

“Yes, of course: still wrestling with ‘window,’ she looks up and is confronted by the equally enigmatic ‘ceiling.’ In fact. I’m sure I played it your psychological way. . . . .”

So just when KG says the evidence of the animals and plants he has seen makes him agree with the clergy that life is an unquestionable and genuine [dar Boga] [God’s gift - which is Fyodor’s very name, Theodore. GB] Fyodor looks at his Darwin, which argues for life as sluchaynaia, and smiles at what seems a (ne sluchaynoe, not chance) collocation, and remembers this now as he writes. It certainly sounds plausible, even if it doesn’t sound certain.

Will you write up your version of this find as an afternote to mine?

In my current instalment for Ada, I cite Darwin, his The Various Contrivances by Which Orchids are Fertilised

[36]

by Insects, 1862, to be precise, which with its entomological focus and its complex tales of mimicry would be particularly interesting to Fyodor (but “difficult and strange” for a 14-year-old — for this 14-year-old? — not sure).

—Gennady Barabtarlo

SIX NOTES TO THE GIFT

1

As Omry Ronen points out,“prozrachen, kak khrustal’ noe iaitso” (“as transparent as a cut-glass egg:”) bears“a distinct resemblance to the magic crystal in H. G. Wells’ fantasy“The Crystal Egg” (The Nabokovian, 44, 2000). However, there is one more still unrevealed subtext there, a Russian one: in Ivan Goncharov’s short story “The Month of May in St. Petersburg” (Mesiats mai v Peterburge), one character “[...] bought an egg of such a monstrous size somewhere in Nevsky prospect in a foreign shop at Easter that everybody at home gasped. He filled the egg up to the top with candies and brought it to his young sisters for Easter salutation”; “[...) na Sviatoi needle ... kupil gde — to na Nevskom prospekte, v inostrannom magazine, iaitso takoi chudovishchnoi velichini, chto akhnul ves’ dom. On doverkhu nabil iaitso konfetami i prines k sestram-devitsam, chtobi pokhristosovat’sa s nimi' (Complete Collected Works, St. Petersburg, 1899, vol. 11, p. 262). The same is the placement of the shop — in Nevsky prospekt — which is“inostrannyi” (foreign) in both cases, and the size of the purchase (“a Faber pencil a yard long”). One will notice as well that the trademark of the pencil turns out to be a counterpoise to the famous gold-and-enamel Easter eggs by Peter Carl Fabergé.

2

“[...) Furgona uzhe ne bylo... u samoi paneli ostalos’ raduzhnoe, s primatom purpura i peristoobraznim

[37]

povorotom, piatno masla: popugai asfal’ta” D 34

“[...] The van had gone and... there remained next to the sidewalk a rainbow of oil, with the purple predominant and a plumelike twist. Asphalt’s parakeet” G 34-35 The flying birds of Russian literature made several stops before they settled in The Gift. The passage from Vladimir Narbut’s 1922 long poem “Alexandra Pavlovna” reads as follows:

Oranzhevye, raduzhnye peria Orange rainbow plumes

i zhenshchin sudorozhnie glaza, — and convulsive eyes of women, —

pavlinia neft’! peacock’s petrol!

That was taken up by Osip Mandelstam in “Egyptian Stamp” (1925-28):

“Tysiachi glaz gliadeli v neftianuiu raduzhnuiu vody, blestevshuiu vsemi ottenkami kerosina perlamutrovikh pomoev i pavliniego khvosta” [ Thousands of eyes looked at the petrol-rainbow water, glistening with all the kerosene tints of the mother-of-pearl swill and a peacock’s tail”].

3

“[...] v poslednih chislah marta ... V klasse bylo otvoreno bol’shoe okno ... uchitelia propuskali uroki, ostavliaia vmesto nih kak by kvadrati golubogo neba, s futbol’nim miachom, padaiushchim iz golubizny D 115

“[...] during the last days of March ... In the classroom the large window was open ... teachers let lessons go by, leaving in their stead squares of blue sky, with footballs falling down out of the blueness” G 106

On September 4th, 1937, Nabokov wrote a letter to his best friend at Tenishev school, Samuil Rozov, who had moved to Palestine. This letter (now in the private collection) contains several autobiographical flashes of The Gift, in progress at the time: “ Vesnoi uchitelia, pomniu,

[38]

propuskali uroki, ostavliaia kak by kvadrati golubogo neba s futbol’nim miachom, padaiushchim iz golubizni”

[“In spring, I remember, teachers let lessons go by, leaving as it were squares of blue sky, with a football dropping down out of the blue”].

4

“[...] pripisyvaiemye [Turgenevu] slova, kotorymi v molodosti on odnazhdi budto by obmolvilsia vo vremia pozhara na korable:“Spasite, spasite, ia edinstvennyi syn u mated". D 268

“[...] the unfortunate words which in his youth he had allegedly addressed to a sailor during a fire on board ship: ‘Save me, save me, I am my mother’s only son’” G 238 This accident happened to the young Turgenev in May of 1838. It was described in Pisania I. S. Turgeneva, ne vkliuchennye v sobraniia ego sochinenii ([Works not included in his collections] Vol. 3, Moscow, 1916), and reproduced in part in A. G. Ostrovsky’s Turgenev v zapisiakh sovremennikov, [Turgenev in the Records of His Contemporaries] Leningrad, 1929. The latter could serve as a source for Nabokov:

“Kniaziy P. V. Dolgorukovy zablagorassudilos’ vikopat' starii anekdot o tom, kak ... ia na “Nikolaye I”, sgorevshem bliz Travemunde, krichal: “Spasite menia, ia— edinstvennyi syn u materi!” (ostrota tut dolzhna sostoiat’ v tom, chto ia nazval sebia edinstvennym synom, togda kak u menia est’ brat)... ia ne nameren uveriat’ chitatelia, chto gliadel na [smert’J ravnodushno, no oznachennykh slov... ia ne proiznes”. [“ Prince P. V. Dolgorukov thought it fit to unearth an old yam concerning my crying on board of “Nicholas I”, which burned down near Travemunde: ‘Save me, — I am my mother’s only son!’ (the sarcastic point here is supposed to consist in the fact that I called myself the only son, while I have a brother)... This is not my aim to persuade the reader that I was staring at [death] indifferently, yet I did not utter the aforesaid words”].

[39]

5

“[...] Byt’ mozhet, kogda-nibud’, na zagranichnih podoshvah ... ia eshche vyidu ss toi stantsii ... Kogda doidu do teh mest, gde ia vyros, I uvizhy to-to i to-to...potomu chto glaza u menia vse-taki sdelani iz togo zhe, chto tamoshniaia serost’, svetlost’, syrost’ D 30

“[...] Perhaps one day, on foreign-made soles ... I shall again come out of that station <.. .> When I reach the sites where I grew up and see this and that ... because my eyes are, in the long run, made of the same stuff as the grayness, the clarity, the dampness [serost’, svetlost’, syrost’] of those sites [...]” G 31

The fantasy of returning home alludes to a similar phonetic-semantic play in Marina Tsvetaeva’s poem “Rassvet na rel’sakh” [Daybreak on the Rails] (October 12, 1922. Translations of the poems are mine — Y. L.):

“...Rossiju vosstanavlivayu ... / Iz syrosti — i svai, / Iz syrosti — i serosti <...> Iz syrosti — i shpal, / Iz syrosti — i sirosti ...” [“...I am reconstructing Russia... / from dampness — and from bearing piles, / from dampness — and grayness <...> from dampness - and railway ties, / from dampness — and shabbiness...”].

It was suggested that Nabokov echoed Tsvetaeva’s poem in The Gift (See, Fyodor Dvyniatin, “Nabokov i futuristicheskaia traditsia”, Vestnik filologicheskogo fakul’teta, 2/3, SPb, 1999, P. 137). In fact, a year before Tsvetaeva, Nabokov had published his poem “On a Train” in Rul’ (July 10, 1921):

Vnimaia trepetu i pen’u.

smolkaiushchikh koles, — ia ramu opustil:

pakhnulo syrosti’u, siren’u!

[“Harking to the shudder and whine / of the wheels decelerating into silence, I pulled down the window, / and the waft of lilacs and dampness (syrost’iu, siren’iu) rushed in!”]

Both poems describe the coming back to Russia, but Tsvetaeva adds the word shabbiness [sirost’]. Nabokov’s poem appeared under his penname Sirin. Both poets met

[40]

on January 24, 1924, in Prague. In 1927 Nabokov develops the triad syrost’ - serost’ - sirost’ as a euphemistic code for S-S-S-R (the USSR). He proposes a similar decoding for the abbreviation in the essay “Iubilei”, written on the occasion of the Bolshevik coup: ‘These very days, when they celebrate their gray, s-s-erish [seryi, esesernyi] jubilee, we celebrate the decade of contempt, faithfulness, and freedom” (Sobranye Sochinenii, “Symposium”, St. Petersburg, 1999, Vol. II, P. 647). A year later he fills the lexical stock for the future novel The Gift in the poem “Siren”’ (Rul’, May 13, 1928): “The night... quavered with the lilac, gray [siren’iu, seroi] <...> My night is misty and light [svetla]”.

6

“[Ö] S izognutoi lestnitsi podoshedshego avtobusa spustilas’ para ocharovatel’nykh shelkovykh nog: my znayem, chto eto vkonets zataskano usiliem tysiachi pishushchikh muzhchin, no vse-taki oni soshli, eti nogi — i obmanuli: lichiko bylo gnusnoe” D 183

“[...] Down the helical stairs of the bus that drew up came a pair of charming silk legs: we know of course that this has been worn threadbare by the efforts of a thousand male writers, but nevertheless down they came, these legs - and deceived: the face was revolting” G 157

One of “a thousand male writers”, probably the first to use the pattern, is Alexander Pushkin:

“[...] Ulitsa byla zastavlena ekipazhami, karety odna za drugoiu katilis’ k osveshchennomu pod’ezdu. Iz karet pominutno vitiagivalis ’to stroinaia noga molodoi krasavitsi, to gremuchaia botforta, to polosatyi chulok ...” (A. S. Pushkin, Polnoe Sobranie sochinenii v 10 tomakh, Moscow, 1964, Vol. 6, P. 332).

“[...] The street was crowded with vehicles; one after another, carriages rolled up to the lighted entrance. From them there emerged, now the shapely little foot of some beautiful young woman, now a rattling jack-boot, now the striped stocking...” (A. S. Pushkin, The Queen of Spades”, Transl. by Gillon R. Aitken, The Folio Society,

[41]

London, 1970, P. 23).

Another “male writer” is James Joyce, to whom Nabokov offered, in 1933, his expertise to translate Ulysses into Russian:

“[...] Watch! Watch! Silk flash rich stockings white. Watch!

A heavy tramcar honking its gong slewed between.

Lost it. Curse your noisy pugnose.” U 61

Abbreviations:

D — Vladimir Nabokov, Dar, Omsk, 1992.

G — Vladimir Nabokov, The Gift, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1963.

U — James Joyce, Ulysses, London: The Bodley Head, 1986.

— Yuri Leving, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

SOME NOTES ON THE VARIANTS IN PALE FIRE PART I

Close examination of the variants provided by Charles Kinbote in his Commentary on John Shade’s poem, “Pale Fire”, yields clues that aid in understanding Nabokov’s novel, Pale Fire. The first step is to establish Kinbote’s involvement in the writing of the variants, in light of the doubts that may arise, not only from the novel, but from a troubling interview response given by Nabokov. Kinbote says of the variants in his Foreword that “Another, much thinner, set of a dozen cards, clipped together and enclosed in the same manila envelope as the main batch, bears some additional couplets ... among a chaos of first drafts. As a rule, Shade destroyed drafts the moment he ceased to need them ... But he saved those twelve cards because of the unused felicities shining among the dross of used draftings.”(p. 15)

Three of these variants are actually the work of Kinbote. Their subject matter and their identification in the Index as “K’s contribution” belie his imprecise and disingenuous claim that “in [Shade’s] draft as many as

[42]

thirteen verses, superb singing verses...bear the specific imprint of my theme”, (p.81 -82) After recounting Shade’s death, and in a pre-emptive response to the “lies” that will be told in contradiction of his version, he allows that “Mrs. Shade will not remember having been shown by her husband who ‘showed her everything’ one or two of the precious variants.”(p.297) In other words, his ego requires him to take credit for writing his additions while at the same time it wants to convince us that Shade was sufficiently captivated by him to have written them. In addition to his three “contributions”, Kinbote rather hopefully believes that two others alluded to him as well.

Despite his egomania and his feeling of betrayal upon reading “Pale Fire”, he is not completely bereft of integrity. He refrains from altering Shade’s creation. He might, for example, have foisted on the reader as an actual variant, “killing a Zemblan king”, in his note to line 822, or he might even have gone so far as to insert it into the poem itself; instead, he says “... alas, it is not so: the card with the draft has not been preserved by Shade.”(p.262) His first counterfeit attempt (“Ah, I must not forget to say something/That my friend told me of a certain king”) is so obviously clumsy that he admits his forgery in the Note to Line 550 and omits it from the indexed variants.

The variants that do appear in the index are seventeen in number. (For a possible numerical correspondence between these seventeen variants and the eighty index cards bearing the poem, on the one hand, and the eighty alphabet recitations with seventeen false starts in the haunted barn episode, on the other hand, see my note in The Nabokovian #44.) Although some of the variants seem not as rich in thematic interconnections as others, I will include all of them for the sake of comprehensiveness and as a possible prod to further investigation.

1. …...........and home would haste my thieves,

The sun with stolen ice, the moon with leaves

(p.79)

Kinbote, in his note to Lines 39-40, is reminded by this variant of a certain passage in Timon of Athens,

[43]

which he retranslates into English from the Zemblan version of his uncle, Conmal. (Might that name be deciphered as: con = to know, to study carefully, to memorize, to learn; mal = badly, poorly?) Shakespeare’s original passage (IV, iii, 435-442), unbeknownst to Kinbote, is the source of the title of Shade’s poem. In Shakespeare, the sun is masculine (“... and with his great attraction/Robs the vast sea.”) and the moon feminine (“And her pale fire she snatches from the sun.”), while in Zemblan the genders are reversed (‘The sun is a thief: she lures the sea/And robs it. The moon is a thief:/he steals his silvery light from the sun.”) This is in keeping, of course, with the inverted sexuality of Kinbote’s Zembla, and is an instance of the gender-switch theme that permeates the book, often in understated fashion. (Example: “... the Italianate villa built by Queen Disa’s grandfather in 1908, and called then Villa Paradiso, or in Zemblan Villa Paradisa” — p.204) The theme is emphasized, both in Kinbote’s Note to Line 819 and his Index, via a game of word golf: “lass-male in four”, (p.262)