Download PDF of Number 5 (Fall 1980) Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter

THE VLADIMIR NABOKOV

RESEARCH NEWSLETTER

Number 5 Fall 1980

________________________________________________

CONTENTS

1980 Annual Meeting

The Vladimir Nabokov Society 3

News Items and Work in Progress

by Stephen Jan Parker 5

Abstract: Donald Hutton Stanley,

"The Self-Conscious Narrator in Donald Barthelme

and Vladimir Nabokov" (Ph.D. dissertation) 12

Abstract: Sylvia Jane Paine,

"Sense and Transcendence: The Art of Anais Nin,

Vladimir Nabokov, and Samuel Beckett (Ph.D. dissertation). 15

Abstract: Edward Delafield Ruch Jr. ,

"Techniques of Self-Reference in Selected Novels of

Beckett, Nabokov, Vonnegut, and Barth" (Ph.D. dissertation) 17

Presentation Butterflies 19

Abstract: Jay Alan Edelnant,

"Nabokov's Black Rainbow: An Analysis of

the Rhetorical Function

[2]

of the Color Imagery in Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle"

(Ph.D. dissertation) 23

Annotations & Queries

by Charles Nicol

Contributors: Douglas R. Fowler, Charles Nicol 26

Bibliography

by Stephen Jan Parker 29

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 5, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

[3]

1980 ANNUAL MEETING

THE VLADIMIR NABOKOV SOCIETY

The annual meeting of The Vladimir Nabokov Society with a special section devoted to Nabokov scholarship will be held this December in Houston. It will not, however, be in direct conjunction with the annual convention of the MLA. That organization once again rejected our formal request for a special section and, moreover, informed us that there is now a moratorium of indefinite duration on accepting groups into the MLA under "affiliated organization" status.

We have turned to the other organization which seems a natural choice for affiliation. AATSEEL (The American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages) is the major professional organization to which Nabokovphiles in Slavic studies belong. Its annual convention is coterminus with the MLA (same dates, same place) and thus offers the same opportunity to bring together Nabokov Society members from the various disciplines. Our request for inclusion in AATSEEL's official program has been met with encouragement and enthusiasm .

Therefore NOTE: The 1980 meeting of the Nabokov Society and the Nabokov section will be held on Monday, December 29, from 7:00-9:00 pm, in High Chaparral Salon III of the Marriott Hotel (at the Astrodome, 2100 S. Braeswood at Greenbrier Dr., Houston). The section, chaired by Samuel Schuman, is entitled "Speak On, Memory: Problems of

[4]

Autobiography as Fiction in the Novels of Vladimir Nabokov." The program has: Timothy Shipe, "Nabokov's Metanovel"; Geoffrey Green, "'Nothing will ever change, nobody win ever die': The Speech of Memory in Nabokov's Fiction"; J.D. O'Hara, "The 'Tamara Theme' in Nabokov's Life and Several Works"; Ellen Pifer, "Nabokov's Gift: The Art of Exile"; Respondent, D. Barton Johnson; Special Report, John V. Hagopian, "Underground Nabokov Scholars in the USSR." The business meeting of the Nabokov Society will follow upon completion of the formal program.

Consideration of a permanent affiliation with AATSEEL will be one item of business at the Society meeting. After some years of intensive efforts to reach an accommodation with the Modern Language Association we must now conclude that Nabokov and Nabokov affairs are not welcome there. AATSEEL offers an ideal alternative and some special advantages. For one, the dues structure is significantly lower than the MLA; for another, the convention room rates have always been better than the MLA. Most importantly, AATSEEL enthusiastically ~ welcomes our presence and this year has scheduled our meeting at a time and place which promises to insure a good attendance. Those who wish to join AATSEEL prior to the convention may write Professor Joe Malik, Jr., Modern Languages 340, Department of Russian and Slavic Languages, University of Arizona, Tucson, 85721.

[5]

NEWS ITEMS AND WORK IN PROGRESS

By Stephen Jan Parker

VNRN circulation is now steady at approximately 220, with subscribers in the USA, Canada, England, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Holland, Finland, Yugoslavia , Australia, and New Zealand. Complimentary reviews have appeared in Germany and England, in the USA and Canada. The VNRN is recognized as an essential source of bibliographic information, news, and abstracted items relative to Vladimir Nabokov and his writings. A new dimension, as you win note in this issue, is the inclusion of graphic materials. To date, however, we have not received reminiscences or documents (letters, etc. ) for publication. Since the continued success of the Newsletter is largely dependent upon a regular flow of information and items from its readers, may I ask each of you to use the occasion of sending your 1981 dues/subscription fee to convey to the editor all news and materials suitable for publication.

*******

Scholars working with The Nabokov-Wilson Letters (1979) should be aware that the paperback edition published in 1980 (Harper Colophon Books/CN 753) is the more reliable edition. Some fifty-seven corrections of copy in the hardbound edition, many of them quite substantive, have been incorporated into the paperback edition. Aside

[6]

from errors of the typesetting sort (punctuation , capitalization, etc.), notes have been added and/or corrected and the dates and order of some letters have been changed. For example, the order of letters 7 and 8 in the hardback should be reversed, with the date for 7 changed to February 9, 1941. Letter 252 should be numbered 257, with the date changed to May 24, 1958; letters 253-256 should then be renumbered accordingly.

Professor Karlinsky writes us that the reason for such a large number of corrections was that "some of Nabokov's letters came to me as xeroxes of originals, but others were copies by someone in Switzerland. Since the book's publication, I was given access to the originals and the postmarked envelopes in the Beinecke Library [Yale University].11 He also notes, "we will have to wait for the second edition, when and if it comes, to include the additional letters that have come to light in the meantime in the Nabokov archive in Montreux and at the Beinecke Library (where they were misfiled earlier). ”

Three papers on Nabokov appear on the AATSEEL program apart from the Nabokov Society session. David Lowe, Vanderbilt University, will present "Pushkin in Nabokov's Despair" in the panel Twentieth Century Russian Fiction, Sunday, December 28, 1:15-3:15 pm. On Monday, December 29, 1:00-3:00 pm, in the panel Problems of Translation, Judson Rosengrant, Reed College, will speak on "Nabokov's Autobiography: Translation and Style" (Professor

[7]

Rosengrant writes that his paper will address the English and Russian versions of the autobiography from the point of view of style). Stephen W. Nielsen, Harvard University, will give a paper, "Fire as Hope in a Distant Land: Nabokov's Pale Fire," in the session The Theme of Fire in Russian Literature, Tuesday, December 30, 8:30-10:30 am.

Mrs. Vera Nabokov notes the following publishers who have obtained rights to Vladimir Nabokov. Lectures on Literature: TBS Britannica, Japanese language rights for both volumes; Weidenfeld, United Kingdom rights for both volumes; Garzanti, Italian language rights for Volume I; Librairie Arthème Fayard, French language rights for both volumes; Editorial Bruguera, Spanish language rights for both volumes. Excerpt rights have been obtained by Cornell Alumni News, Antaeus, American Poetry Review, Partisan Review (Kafka section, issue no. 3, 1980), Esquire ("How to Read, How to Write," September 1980).

Recent newspaper stories indicate that the Edward Albee dramatization of Lolita will open in Boston at the Wilbur Theatre on January 23, 1981, prior to moving to Broadway the week of February 16. The production will be directed by Frank Dunlop and produced by Jerry Sherlock, with Donald Sutherland in the role of Humbert. Auditions were held recently in New York to choose the 11-13 year old to play the part of Lolita. According to a New York Times

[8]

article, Mr. Albee "has made some changes from the novel in telescoping and dramatizing it, but hopes that, 'with any luck, people won't know which is Nabokov and which is Albee.'" The Sunday New York Times has run an advertisement seeking investors for the production - The New Lolita Company.

Bruccoli Clark Publishers (1700 Lone Pine Road, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013) has announced the publication of a collector's issue of Nabokov's Lectures on Ulysses: A Facsimile of the Manuscript. The volume is a specially printed and bound, limited and numbered (450 for sale) facsimile of the 133 pages of Nabokov's classroom script for the lectures on Ulysses, including as well his maps, diagrams, and various jottings.

Laurie Clancy (Dept, of English, La Trobe University, Bundoova 3083, Australia) writes that he is at work on a book on Nabokov's novels which has been contracted to Macmillan, London and tentatively entitled, Sufficient Worlds: The Novels of Vladimir Nabokov.

Tim Gorelangton (Special Collections, The University Library, The University of Nevada-Reno) once again brings to our attention the existence of three separate states or variants of the first edition of a Nabokov work. The variants of The Waltz Invention (Field #1072) were discovered by David J. Angsten (824 Roscoe, Chicago, IL 60657) and confirmed by Mr. Gorelangton.

[9]

They are as follows:1. 8 mm. thick (across top edge of pages, not counting binding), had red end papers, light blue binding with black signature, is printed on white paper, has two jacket flap addresses, and the jacket is black and red on white; 2. 9.5 mm. thick, has white end papers, light blue binding with black signature, is printed on white paper to page 24, then on off white (almost beige — perhaps pulp?) paper to the end of the book [p. 111-112], has two jacket flap addresses, and the jacket is also black and red on white; 3. almost exactly 10 mm. thick, has white end papers, dark blue binding with black signature, is printed on white paper, has one [different] jacket flap addresses, and the jacket is white and red on blue with a picture of Nabokov on back.

Stephen Parker (Slavic Languages & Literatures, University of Kansas, Lawrence, 66045) has completed an essay on Nabokov for the Dictionary of Literary Biography supplement and is working on the major author entry for Nabokov to appear in the Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet Literature.

Sylvia Paine (Box 322, Moorehead, MN 56560) writes that she is now revising her dissertation (abstracted in this issue) for publication by Kennikat Press under the title, Beckett, Nabokov, Nin: Motives and Modernism.

A recent letter from L.L. Lee (Fulbright Lecturer, Cracow, c/o American

[10]

Consultate General, Warsaw, APO New York 09767) brings the following: "In June one of my students brought me a copy of the Polish journal Przekroj containing a translation of Nabokov's "In Aleppo Once. …" ["Gdy raz w Aleppo …," Przekroj, 8 June 1980, No. 1835, Krakow, pp.1516, trans. Elzbieta Tabakowska]. There is a biographical note accompanying the translation. ... The Polish students had heard of Nabokov but had not, or course, read anything . ... it was rather a pleasure to find N. appearing, with official approval, that far east."

Ardis (2901 Heatherway, Ann Arbor, MI 48104) has announced the publication of Blednyi Ogon', a translation into Russian of Nabokov's Pale Fire, translated by Alexei Tsvetkov. According to their announcement: "Its appearance in Russian is a remarkable event, for the Nabokovs have never allowed others to translate Nabokov's English works into his native language .... it has been supervised by Vera Nabokov, and the solutions she and Mr. Tsvetkov provide to countless problems of translation promise to illuminate many of the novel's mysteries."

A note from Timothy Lucas (3160 McHenry Avenue, 11, Cincinnati, OH 45211) relates the following: "There was a motion picture made in Paris and England in 1973 — King, Queen, Knave — directed by Polish filmmaker Jerzy Skolimowsky. I have found this mentioned nowhere in any Nabokov filmographies to date. I've not seen the film, as it was never released in the USA,

[11]

but did read a review in an early 1974 issue of Sight & Sound, a British publication, which inferred that it was a well-structured if misguided 'bedroom farce.' The film starred David Niven and Gina Lollobrigida. It was based on the Nabokov novel."

The Newsletter would like to acknowledge and thank the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences of the University of Kansas for its continuing support of this publication. Special thanks are due Ms. Nancy Kreighbaum and Ms. Cheryl Berry for their assistance in putting together this issue.

[12]

ABSTRACT

The Self-Conscious Narrator in Donald Barthelme and Vladimir Nabokov

by Donald Hutton Stanley

(Abstract of dissertation submitted for the award of Ph.D., The University of British Columbia, 1979.

The literary device of a self-conscious narrator is prevalent in the works of Donald Barthelme and Vladimir Nabokov. However, the themes and world view of the works are not predetermined by any qualities inherent in the self-conscious narrator. Despite a current critical tendency to suppose that self-consciousness necessarily implies a problematic or solipsistic stance towards both reality and traditional realism, the self-conscious narrator remains a malleable device which can be used in conjunction with traditional realism, and which can be shaped according to the unique purposes of a particular author.

A tendency among certain contemporary theorists — Robert Alter, Susan Sontag, Maurice Beebe and others — would make self-consciousness, rather than realism, central to the tradition of the novel. This tendency represents a phase in the historical pattern by which the self-conscious narrator goes in and out of fashion. In the eighteenth century English novel he appeared to be a sprightly variant of the formal realism of Defoe and Richardson, in that he interrupted the narrative to comment on narrative

[13]

technique, and to emphasize the artificial or contrived aspect of what were otherwise presented as real events. Despite an early fruition in Sterne, the self-conscious narrator's popularity declined, and critics came to regard him as an aberration, and an impediment to the novel's "implicit methods." He revived in the modern era, and at present self-consciousness itself is assumed by some critics to be "at the heart of the modernist consciousness in all the arts." This somewhat exaggerated status of literary self-consciousness leads to a corresponding condescension towards traditional realism, a condescension which is revealed in the critical response to Nabokov's self-conscious narrator.

Some of the criticism of Nabokov is vitiated by the simplistic assumption that Nabokov, the wizard of mirrors and word games, has banished from his novels all traces of the real world. In fact, however, Nabokov's narrators contribute to a unique world view in which there is an implied identity between the fictional world of art and the rules of the universe. The self-conscious narrator emphasizes the artifice of the narrative, but at the same time he personifies, as it were, certain narrative conventions, and adds what Charles Kinbote calls a "human reality." His ongoing dialogue with the reader helps the reader to recognize the false artifice of totalitarian states and totalitarian art, and teaches the reader to regard fictional characters with a sympathetic eye. In the words of Albert Guerard, "Within Nabokov's involutions, behind his many screens, lie real people."

[14]

Donald Barthelme's self-conscious narrators might at first appear to be rather typical spokesmen for certain clichés of avant garde theory: ontological chaos, the breakdown of language and meaning, existential dread. But the narrators are also satirists of avant garde theory, particularly the theory that the literary past has been discredited and language no longer communicates. Rather than intimidating the reader, the self-conscious narrator sometimes acts as his ally, inviting the reader to check the reader's own world ("Look for yourself," says one narrator). Self-consciousness is shown to be part of a malaise in society itself, a malaise that is occasioned not so much by epistemological breakdown as by moral failure. Self-consciousness is a symptom of a society that is at heart evil and murderous.

Barthelme and Nabokov employ their self-conscious narrators to different ends: Nabokov's gifted self-conscious narrator contributes to Nabokov's serene sense of an identity between art and reality; Barthelme discovers a moral failure at the heart of a self-conscious society. The works and world views of each author are made possible by a unique transformation of a traditional narrative convention.

[15]

ABSTRACT

Sense and Transcendence: The Art of Anais Nin, Vladimir Nabokov, and Samuel Beckett

by Sylvia Jean Paine

(Abstract of dissertation submitted for the award of Ph. D., Syracuse University, 1979.)

Though in some ways art distills life, its compelling connection with the world of matter instills in art a unique power to make ideas live through the senses and to extend the sympathies beyond the self. The sensory content of literature, linking the individual writer or reader with the universe of human experiences and emotions, makes writing an act of love with implicitly moral demands. In the fragmented modern world, art is essential as a healing force, and modernist writers meet their felt obligation to create with an understanding of this spiritual imperative.

This dissertation analyzes selected works of three very different twentieth-century writers who evoke the senses in order to transcend them: Anais Nin through incorporation of the material world into the self, Vladimir Nabokov through expansion of the senses beyond the body, and Samuel Beckett through an attempt to expel the frustration of sensory limitations--an endeavor that fails in its intent but releases the very breath of creation. By looking closely at Nin's Seduction of the Minotaur, we see her use of setting as a symbol of the inner self, whose turmoils must be calmed before

[16]

her characters can live fully and confidently in the world of the senses, a potential realized in Collages whose heroine thus becomes universal. Nabokov's The Gift illustrates how his elaborately sensuous language evokes the magic and mystery behind the surface of life, elicits tenderness for all the fragile transparent things that inhibit the world. In turn, this awareness expands the imagination, making possible communion through art. By contrast, Samuel Beckett pares away the sensuous surface, only to reveal the inescapability of the senses, the compulsion of living and dying by them. His Fizzles metaphorically depicts the futility of trying to eliminate "the mess" within man, yet the futile gesture itself assumes a sort of transcendent meaning as a statement of the human condition, an act in recognition yet defiance of despair.

Ultimately, the senses emerge as the source of the ethical dimension of art, that which makes art the progenitor of human understanding, a force that can change the world.

[17]

ABSTRACT

Techniques of Self-Reference in Selected Novels of Beckett, Nabokov, Vonnegut, and Barth

by Edward Delafield Ruch, Jr.

(Abstract of dissertation submitted for the award of Ph. D., The Catholic University of America, 1979.)

It is commonly acknowledged that many twentieth century novelists have abandoned the Jamesian dictum that a novel should create the "illusion of life" and have instead created works which deliberately negate any such illusion, calling attention to themselves as literary constructs. Examples of such self-referring fictions are Beckett's Murphy, Nabokov's Pale Fire, Vonnegut's Slaughter-house-Five and Barth's Chimera. This study describes and classifies the various means by which each of these fictions calls attention to its artifice.

Chapter One surveys twentieth century point of view scholarship, revealing a gradual shift in critical opinion from adherence to a rigid set of formulae based on the tenets of James and his followers, to a more reader-oriented view, which permits a. variety of fictional techniques. This chapter also includes a discussion of contemporary narrative technique and its rationale. Chapter Two shows that in Murphy Beckett employs authorial intrusion, parody of the conventions of realism, foregrounding of

[18]

language, and allusions to closed systems to achieve a frame-breaking effect. Chapter Three reveals that in Pale Fire Nabokov uses parody of literary criticism, narrative point of view, the realistic novel, and detective fiction, as well as foregrounding, recapitulation of previous fiction and allusions to chess to remind the reader of the work's artifice. Chapter Four points out that the major techniques of self-reference in Slaughterhouse-Five are Vonnegut's personal intrusion into the narrative, recapitulation of character and incident from his previous fiction, satire of the realistic novel, and typographical idiosyncrasies. Chapter Five shows that in Chimera Barth employs direct authorial intrusion, recapitulation of his previous literature, parody of classical myth, foregrounding, and typographical idiosyncrasies to break the narrative frame. The conclusion summarizes the major frame-breaking devices shared by the four fictions.

Besides demonstrating the range of formal possibilities available to the artist working in this vein, this study makes five observations about these self-referring works. First, there is a trend toward more personal authorial intrusion in the later works. Second, each of the fictions examined questions the ability of art to capture "objective reality." Third, each author reveals within his work the process of composition. Fourth, the problem of composition is exacerbated by the narrators' belief in the inadequacy of language. Finally, each of these fictions is non-mimetic in that each is about itself rather than human speech or behavior.

[19]

PRESENTATION BUTTERFLIES

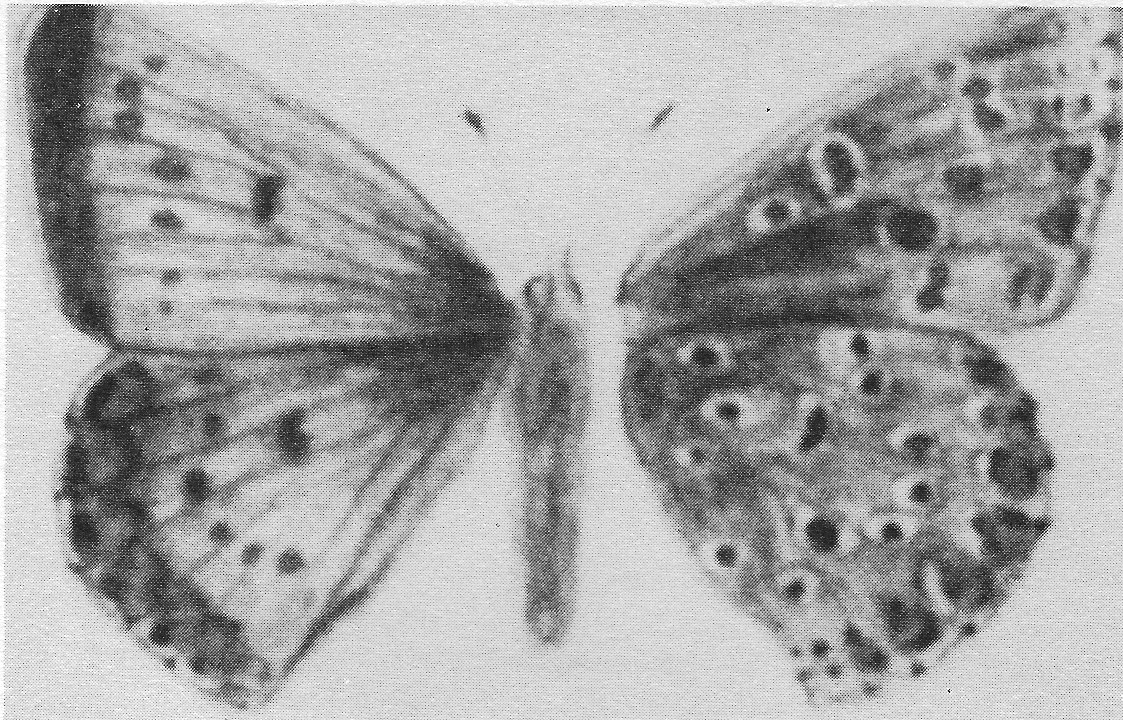

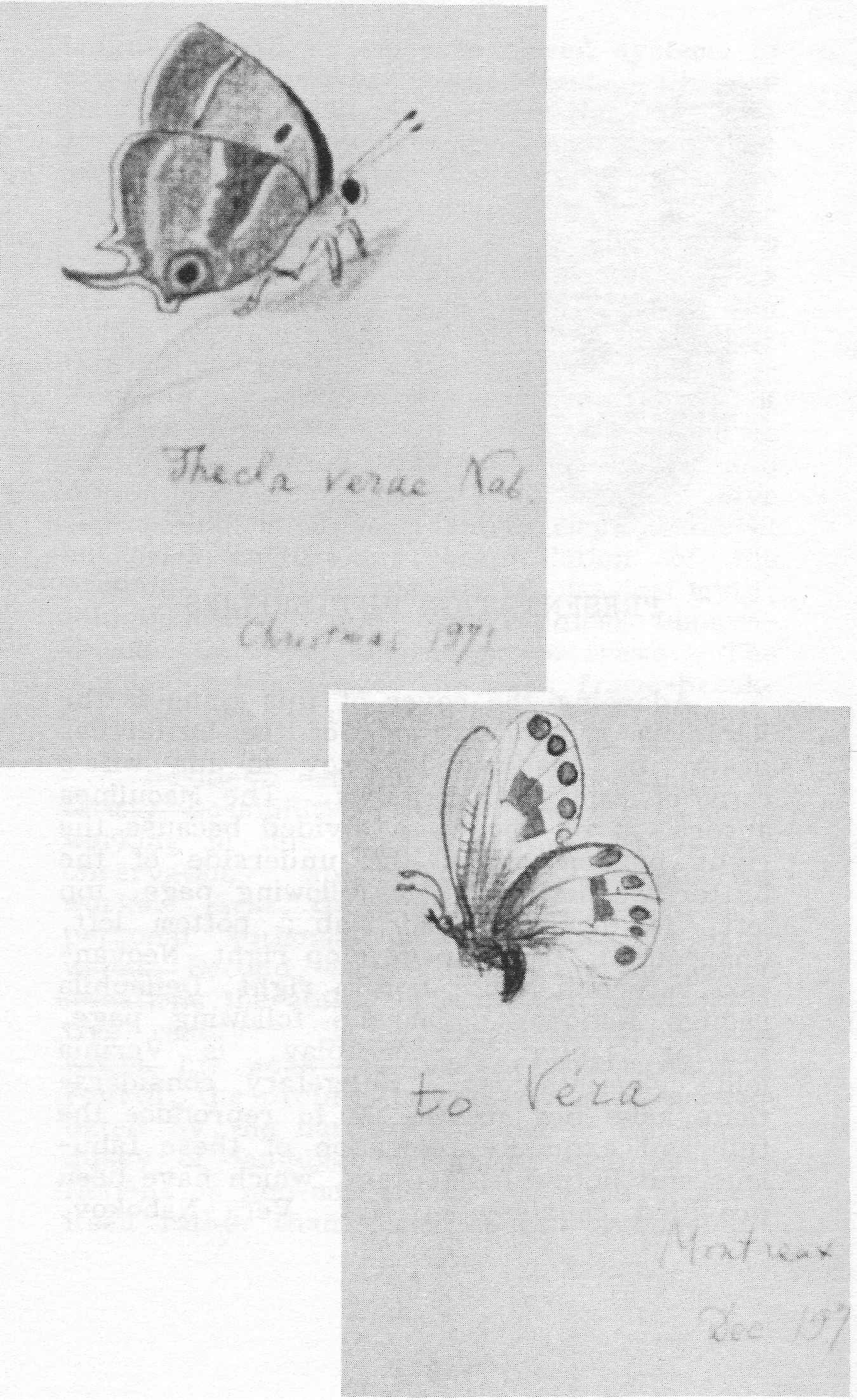

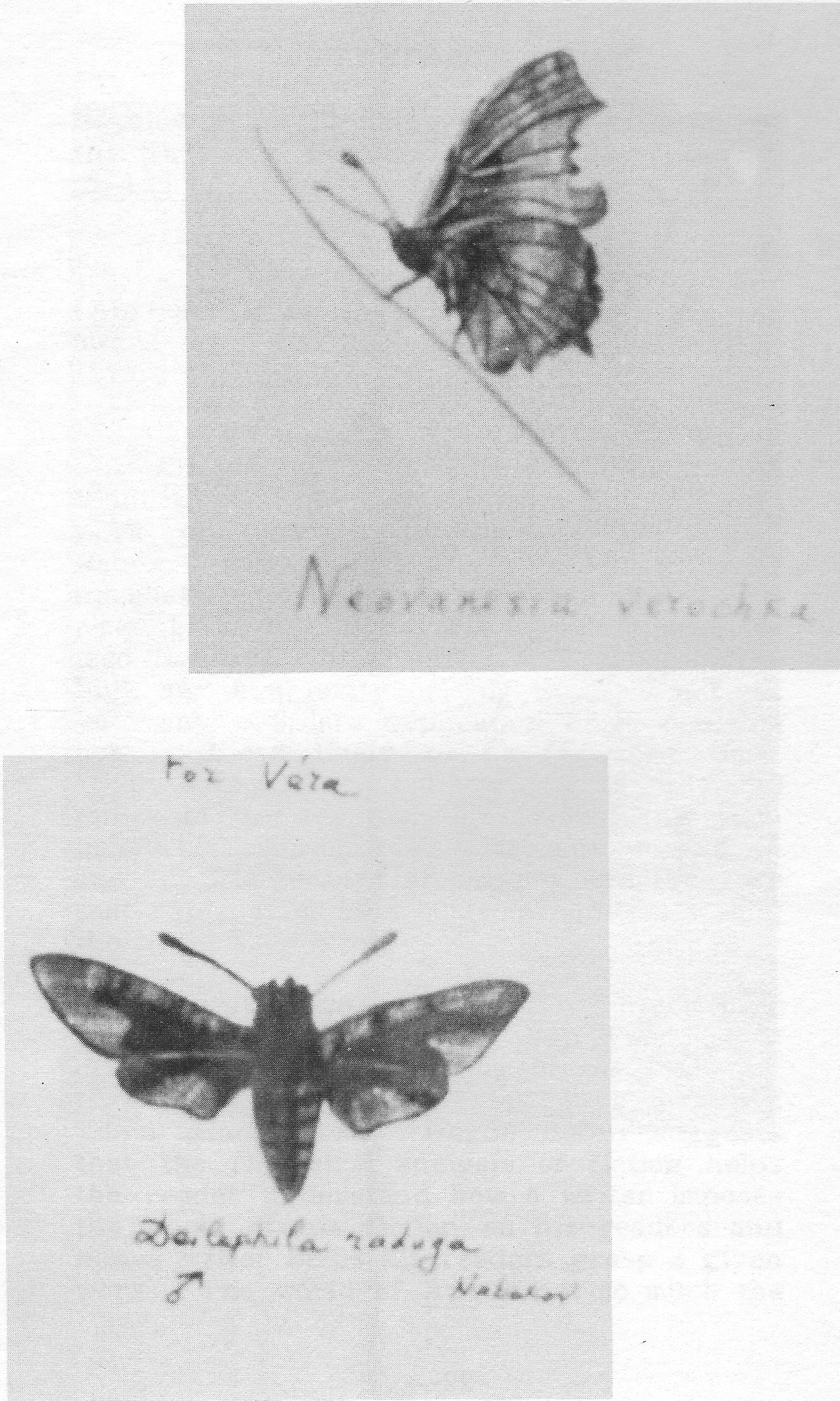

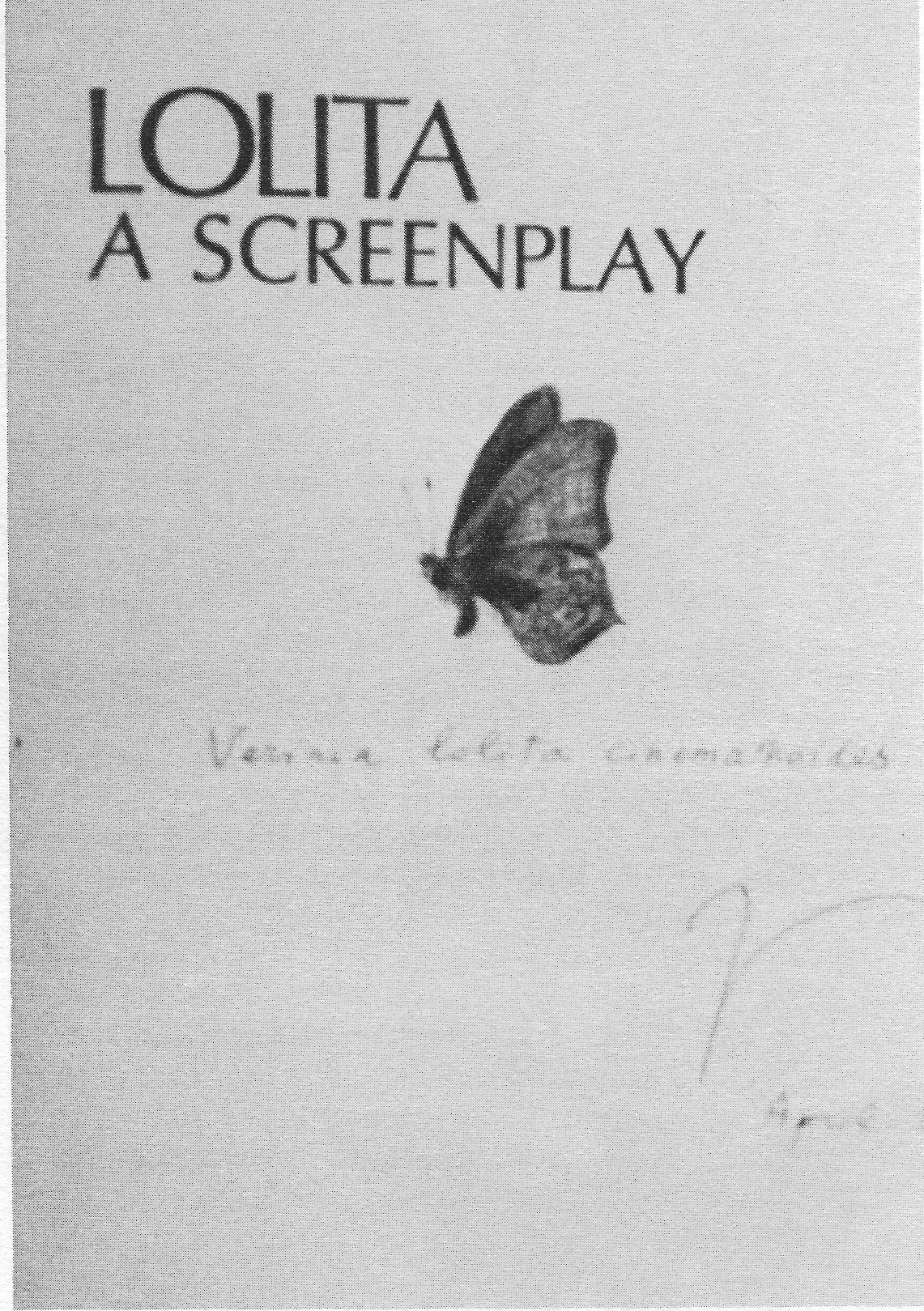

Adorning the cover of this issue is the Paradisia radugaleta, one of the butterflies drawn by Vladimir Nabokov in his wife's copy of each of his works. The Maculinea aurora, given above, is divided because the right portion shows the underside of the butterfly wing. On the following page, top left, is Thecla verae Nab.; bottom left, unspecified; facing page, top right, Neovanesia verochka Nab.; bottom right, Deilephila raduga Nabokov. On the following page, gracing Lolita: A Screenplay, is Verinia lolita cinemathoides. Budgetary considerations have not allowed us to reproduce the full and exquisite coloration of these fabulous and fictive lepidoptera, which have been provided courtesy of Mrs. Vera Nabokov.

[20-21]

[22]

[23]

ABSTRACT

Nabokov's Black Rainbow: An Analysis of the Rhetorical Function of the Color Imagery in Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle

by Jay Alan Edelnant

(Abstract of dissertation submitted for the award of Ph.D., Northwestern University, 1979.)

Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle is Vladimir Nabokov's longest and most difficult work of fiction. Written in 1969, when Nabokov was seventy, it is replete with the novelistic games, convolved structures, and elegant use of language that have characterized Nabokov's other novels. Because of the bulk and complexity of Ada there is not, as yet, any complete explication of it available nor is there likely to be for some time. "Nabokov's Black Rainbow" is intended to follow in the tradition of most of the published criticism of Ada; it attempts to explain one specific pattern of imagery and then use that explanation as a basis for understanding the novel as a whole.

Because Ada is, ostensibly, the memoir of its narrator-protagonist Van Veen, it is crucial to an understanding of the text that the reader be aware of the ways in which Van's mind works. Wayne Booth suggests that the rhetorical analysis of fiction helps the reader understand how a writer imposes the world of his fiction on his readers and how a writer helps his readers grasp a given work. The world of Ada is not so much the

[24]

planet "Antiterra" as it is the mind and memory of Van Veen. Van’s perception of his world is synesthetic and his memory operates through an elaborate system of color correspondences. Nabokov offers the reader of Ada access to Van's mind and its workings through the coloration of the novel. By analyzing the ways in which color is used throughout the novel, the reader should be able to discern the mechanism of Van's mind and also see the way that Nabokov guides his reading of the novel.

The method of "Nabokov's Black Rainbow" is based on Kenneth Burke's "theory of the index." By accumulating an index of "key terms" the analyst is able to note clusters of images that are used repeatedly and derive from them their "principles" by observing them in changing contexts. The method is used to discover an author's "psychosis"—his distinctive artistic vocabulary. The theory of the index is used in this study not to establish Nabokov's "psychoses" but to discover the "psychosis" that Nabokov has given his narrator. Color is the key to Van's mind and his world.

"Nabokov's Black Rainbow" examines each of the major colors of the spectrum as it occurs chronologically in the novel. After an introduction to Ada scholarship, an examination of color theory, and an explanation of Burke's theory, the study examines the primary, secondary, and neutral colors. Blue is discussed in Chapter Two, yellow in Chapter Three, and red in Chapter Four. Chapter Five deals with the secondary colors: green, orange, and purple, and

[25]

Chapter Six discusses the neutral colors: black, white, and gray. The images of the rainbow, the diamond, and other prismatic reflectors are discussed in the concluding chapter. Chapter Seven.

It is the thesis of the study that the use of color in Ada is rhetorically potent; it helps the author impose his fictive world on the reader and, in turn, helps the reader grasp the work. Each color examined in "Nabokov's Black Rainbow" is rigidly controlled by Nabokov. The colors have functions associated with specific characters, emotions, and ideas. The colors are not symbolic; they do not "mean" or "stand for" particular things, but are associative. They form a complex web of cross-references that unifies the action and other image patterns of the novel.

[26]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

(Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov's works will be to the most recent hardcover U. S. editions . )

Elphinstoned Again

(Our first Elphinstone annotation was in VNRN #3, p. 29)

"Elphinstone" (Annotated Lolita, text, pp. 240-49; commentary, p. 346) derives from an old Nabokov favorite, H. G. Wells' War of the Worlds, chapter 16, where it is the name of a crusty and veddy, veddy British "woman in white." She appears as a supernumerary in some of the alarms and excursions during the alien invasion and eventually disappears in a tidal wave of panicky earthpeople fleeing the deadly Heat-Rays employed by the Martians.

—Douglas R. Fowler, English, Florida State University

[27]

Flaubert's Understudy

Ada is, among other things, a history of literature, but one that deliberately jumbles many works and authors. For instance, Lolita has been written by Osberg (Borges) and The Headless Horseman (actually by Mayne Reid) has been written by Pushkin. Some of these confusions

contribute to the novel's anachronisms, and Nabokov's "Notes to Ada by Vivian Dark-bloom" make one of these anachronisms explicit, the impossibly early discussions of Proust: the children's book Les Malheurs de Sophie is "nomenclatorially occupied on Antiterra by Les Malheurs de Swann."

As far as I can see, in Ada the only reference to Flaubert—one of Nabokov's favorite and model authors—is the pseudoquotation from "Floeberg" (p. 128), identified in the Darkbloom Notes as Flaubert. I suggest the lack of further references indicates that Madame Bovary is the "occupant" of Maupassant's "La Parure" ("The Necklace"), which the Darkbloom Notes observe "did not exist on Antiterra."

Maupassant modeled his writing after Flaubert’s, and Mathilde Loisel is clearly modeled after Emma Bovary. Married to a "little clerk," "she suffered ceaselessly, feeling herself born for all the delicacies and all the luxuries.... She thought of the long salons fitted up with ancient silk, of the delicate furniture carrying priceless curiosities, and of the coquettish perfumed boudoirs made for talks at five o'clock with intimate friends, with men famous and sought

[28]

after, whom all women envy and whose attention they all desire" (from the translation by Marjorie Laurie). Mathilde even resembles Emma in despising her husband most at the dinner table.

But at her first, glittering ball, at that moment when her dreams begin to seem possible, Maupassant's heroine diverges from Emma. She loses a friend's necklace, and instead of going on to infidelity and suicide devotes herself to a life of drudgery to repay the debt. This variant on the Bovary story, though no masterpiece in itself (Nabokov lists its faults, Ada, p. 87), presumably appealed to Nabokov as a peculiar wrong turn in literature, a late Bovary time-fork. And noticing that children's books (The Headless Horseman, Les Malheurs de Sophie) are confused with literary masterpieces elsewhere, one might speculate that "Mademoiselle," the French governess immortalized in Speak, Memory who is clearly the original of Ada's Mlle Larivière, adored Maupassant and refused to consider Flaubert's Madame Bovary suitable for children.

Nabokov nicely ties this all up by assigning the governess the name Larivière, combining Maupassant's description of his diamond necklace ("la riviere de diamants") with the name of the specialist who presided over the death of Emma Bovary.— CN