Download PDF of Number 58 (Spring 2007) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 58 Spring 2007

____________________________________

CONTENTS

News

by Stephen Jan Parker 3

Notes and Brief Commentaries

by Priscilla Meyer 6

“Emendations to Annotated Editions Of Lolita”

–Leland de la Durantaye 6

“Hippopotamians in Ardis”

–Matt Brillinger 20

“Rembrandt’s Deposition from the Cross

in The Gift”

–Gavriel Shapiro 24

“An Additional Source for a Central Asian Episode

in The Gift”

–Victor Fet 31

“Incest as a Theme in Lolita”

–John A. Rea 37

“The Fair Invention in Nabokov’s Ada And Gorky’s

“The Life of Klim Samgin”

–Alexey Sklyarenko 43

“Three Allusions in Pale Fire”

–Matthew Roth 53

Annotations to Ada: 27

Part I Chapter 27 Second Section

by Brian Boyd 61

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 58, except for:

- Brian Boyd’s “Annotations to Ada” (because superseded by, updated, hyperlinked and freely available on, his website AdaOnline).

In some but not all cases the downloadable pdf version of the print Nabokovian will have the annual bibliography and the “Annotations to Ada.”

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

Nabokov Society News

The President of the Society is Zoran Kuzmanovich and the Vice-President is Julian Connolly. In 2006, the Society had 163 individual members (117 USA, 46 abroad) and 93 institutional members (75 USA, 18 abroad). Society membership/ subscription income for the year was $6,341; expenses were $5,498. The upsurge in income was due to the significant generosity of Dmitri Nabokov. Also, thanks to the generosity of its members, in 2006 the Society forwarded $405 to The Pennsylvania State University for support of the Zembla website.

*****

Odds and Ends

– The annual MLA Nabokov Society sessions this year – to be held in Chicago, Dec. 28-30 – will be (1) “Nabokov and the Fairy Tale,” chaired by Charles Nicol and (2) “Open Session,” any topic, chaired by Ellen Pifer.

– NOJ/NOZh: Nabokov Online Journal is a new refereed bilingual (English/Russian) electronic edition devoted to Nabokov studies, to be published two times per year. Contributions may be in English, Russian, French, or German. For information, the editor, Yuri Leving, may be reached by email at yleving@gmail.com

– The Nabokov Museum takes an exhibition abroad this year

[4]

for the first time: April 13 - May 19 in London, July in Oxford. The exhibit “unites four St. Petersburg artists who belong to different generations: photographer Yuri Molodkovets, scientific illustrator Natalia Florenskaya, artist Alexander Florensky and designer Mitya Hasrshak. These artists have created work devoted to the main trends of Vladimir Nabokov’s creative activity: literature, chess and entomology.”

– Gerard de Vries and D. Barton Johnson’s book, Nabokov and the Art of Painting ( 384 pages, 80 illustrations) has recently been published by Amsterdam University Press. It is available in the USA through the University of Chicago Press and in Europe through NBVN International Ltd.

– From Brian Boyd: AdaOnline has moved to a new location, at the University of Auckland rather than Penn State. The new URL is http://www.arts.auckland.ac.nz/ada if you would like to have a look. If you have AdaOnline bookmarked, please change the bookmark.

*****

Corrections and clarifications regarding the Fall 2006 issue:

(1) Photos accompanying Gavriel Shapiro ’ s “Rembrandt’s Deposition from the Cross in The Gift” were unpublished. Therefore the entire piece, with the essential photos now included, are to be found in this issue.

(2) For clarification, in regard to item one under “Works” in the 2005 Nabokov Bibliography: Alphabet in Color consists of VN’s description of audition colorée from Speak, Memory, illustrations by Jean Holabird, and an introduction by Brian Boyd (p. 77).

(3) In the 2005 Nabokov Bibliography there is a typographical mistake which incorrectly spells the name Stanislav Shvabrin (p. 83) and an incorrect statement of the title of Gabriel

[5]

Shapiro’s piece, “Artist Exiled, Art Treasures Sold” (p. 86).

*****

As I have for so many years, I wish once again to express my greatest appreciation to Ms. Paula Courtney for her essential on-going assistance in the production of this publication.

[6]

NOTES AND BRIEF COMMENTARIES

By Priscilla Meyer

Submissions, in English, should be forwarded to Priscilla Meyer at pmever@weslevan.edu. E-mail submission preferred. If using a PC, please send attachments in .doc format; if by fax send to (860) 685-3465; if by mail, to Russian Department, 215 Fisk Hall, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT 06459. Deadlines are April 1 and October 1 respectively for the Spring and Fall issues. Most notes will be sent, anonymously, to at least one reader for review. If accepted for publication, the piece may undergo some slight editorial alterations. Please incorporate footnotes within the text. References to Nabokov’s English or Englished works should be made either to the first American (or British) edition or to the Vintage collected series. All Russian quotations must be transliterated and translated. Please observe the style (American punctuation, single-spacing, paragraphing, signature, etc.) used in this section.

EMENDATIONS TO ANNOTATED EDITIONS OF LOLITA

Generations of readers and scholars have much benefited from Alfred Appel Jr.’s The Annotated Lolita. Appel’s notes contain a great deal of interesting, intelligent and concisely expressed information, as well as some genuine moments of charming irreverence and inconsequence. Though fairly irrelevant from the point of view of scholarly annotation, Appel’s recounting, spurred by the mere mentioning of Maeterlinck, of how Louis B. Mayer had brought the writer to Hollywood in the 30’s, commissioned from him a screenplay, and received a work of Symbolist scenography with a bee for a hero is a pleasure to read. It is at such moments that one can

[7]

understand why Gore Vidal, upon the publication of The Annotated Lolita, thought the edition was a hoax and that Alfred Appel Jr. was nothing but Nabokov in disguise. In addition to being witty, urbane, and informative, the notes are a particularly valuable resource. Composed as they were with the help of Nabokov himself, they offer a rare insight into the author’s conception of his work and what the reader needs to know to understand it. (The Nabokov Archive in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library contains two typescripts submitted by Appel to, and corrected by, Nabokov. The numerous admonitions—the phrase, “please, don’t’’ recurs often—and notations in Nabokov’s hand to be found in the margins of these typescripts did much to shape the final product, and had the happy effect of eliciting original comments and commentaries on Nabokov’s part).

However, Appel’s notes present two problems. The first is a structural one. Appel lets whole barns of cats out of Lolita’s bag, beginning with his entries for the book’s opening chapter. The idea of disclosing the novel’s conclusion to the reader at the outset of the book seems to run counter to the aims of a novel, as well as to Nabokov’s professed desire to make the reader work as he did. Appel’s notes make them for this reason difficult to use for the readership they would best serve: high school students, undergraduate university students and interested non-specialist readers reading the work for the first time. This is a problem which only the complete and consequent reworking of the notes can remedy. The second problem with these notes is that a number of factual errors slipped through the net that Nabokov placed below Appel’s composition of these notes. Such things are inevitable and do nothing to detract from the considerable achievement of the editor. The following few emendations offered below note a few errors and offer provisional annotations. At the end of this short list are a few remarks on Brian Boyd’s sparer annotations to the Library of America edition of Lolita.

[8]

Page 5. Note 1 (p. 324). “moral apotheosis." The deceptively perceptive John Ray Jr. tells us that what we are to read is “a tragic tale tending unswervingly to nothing less than a moral apotheosis” (AL, 5). The epithet is doubtless inflationary, but it should not prevent us from seeking its referent. Humbert is hardly promoted to divine status, and does not make a strong case for canonization. But he does appear to do something laudable. This “moral apotheosis” is best sought for in Lolita's tenderest chapter, where we read:

Somewhere beyond Bill’s shack an afterwork radio had begun singing of folly and fate, and there she was with her ruined looks and her adult, rope-veined narrow hands and her goose-flesh white arms, and her shallow ears, and her unkempt armpits, there she was (my Lolita!), hopelessly worn at seventeen...and I looked and looked at her and knew as clearly as I know I am to die, that I loved her more than anything I had ever seen or imagined on earth, or hoped for anywhere else. She was only the faint violet whiff and dead leaf echo of the nymphet I had rol led myself upon with such cries in the past; an echo on the brink of a russet ravine, with a far wood under a white sky, and brown leaves choking the brook, and one last cricket in the crisp weeds...[Nabokov’s ellipses] but thank God it was not that I worshiped. What I used to pamper among the tangled vines of my heart, mon grand pêché radieux, had dwindled to its essence: sterile and selfish vice, all that I canceled and cursed. You may jeer at me, and threaten to clear the court, but until lam gagged and half-throttled, I will shout my poor truth. I insist the world know how much I loved my Lolita, this Lolita, pale and polluted and big with another’s child, but still gray-eyed, still sooty-lashed, still auburn and almond, still Carmencita, still mine....No matter, even if those eyes of hers would fade to myopic fish, and her nipples swell and crack, and her lovely young velvety delicate delta be tainted and tom—even then I would go mad with tenderness at the

[9]

mere sight of your dear wan face, at the mere sound of your raucous young voice, my Lolita (AL, 278; Nabokov’s italics).

Nabokov was to remark of this scene years later that in reading it, “le bon lecteur devrait avoir un picotement au coin de I’oeil” [“the good reader should feel [here] the forerunner of a tear”] (Interview with Anne Guérin, 27). In another interview, Nabokov himself confessed to having felt more than a forerunner, and to having written the passage through his own tears (Interview with Les nouvelles littéraires, 17). Without explanation, Appel locates this apotheosis in the closing lines of the book where Humbert hears the chorus of children’s voices and recognizes the real tragedy being the absence of Lolita’s voice therein (“...and then I knew that the hopelessly poignant thing was not Lolita’s absence from my side, but the absence of her voice from that concord” [AL, 308]). It should be remembered that there is nothing morally decisive about Humbert’s realization in this scene. It is a tragic moment, but involves no moral turn. And, consequently, it changes nothing in his behavior. When we replace this scene, recounted at the very end of the book, in its actual chronology, we remark that this supposed moral turn does not prevent him from continuing to search for his lost love with the same desperate intensity. This has not prevented Vladimir Alexandrov from concurring with Appel on the matter (without noting Appel’s precedent— cf. Alexandrov’s Nabokov’s Otherworld. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991. 171). Both in his Vladimir Nabokov. The American Years (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991, 249) and in “Even Homais Nods” (Nabokov Studies. 2 [1995], 62-86; 85), Boyd locates Humbert’s “great epiphany” in “the scene above Elphinstone.”

The question as to whether this is the sort of remark which needs to be annotated in this way in such an edition is another question. For a popular edition such as The Annotated Lolita

[10]

it seems to me that a definition and summary history of the term apotheosis would suffice.

Page 9. “Lo-lee-ta....Lo. Lee. Ta.” In Appel’s note to this line he cites Nabokov’s remark from an interview which Appel himself conducted with Nabokov and where Nabokov states that Lolita, “should not be pronounced as... [A.A. Jr. ’s ellipses] most Americans pronounce it: Low-lee-ta, with a heavy, clammy ‘L’ and a long ‘O.’ No, the first syllable should be as in ‘lollipop,’ the ‘L’ liquid and delicate, the ‘lee’ not too sharp. Spaniards and Italians pronounce it, of course, with exactly the necessary note of archness and caress” (cited at AL, 328). What Appel does not note—nor as, it seems, have later critics—is that such a pronunciation is incompatible with how the name is written in the text. Humbert writes: “Lo. Lee. Ta.” If we pronounce his beloved’s name as he directs us to, with a period and two spaces which separate it form the next syllable, then the ‘o’ is inevitably long. What is more, when we consider Dolores’ given name, the pronunciation Humbert offers (rather than the one Nabokov recommends in the Playboy interview) is the more logical one: Dolores is called Lo by her mother, and others. Lolita, Humbert’s unique name for her, would then likely take off from the earlier diminutive (Lo). It is my sense that Nabokov’s remark is not an intentional contradiction but simply a change of phonetic preference.

10. “paleopedology and Aeolian harps.” Appel correctly glosses “paleopedology” as “the branch of pedology concerned with the soils of past geological ages” but fails to note the pun: the study of past pedophiles.

16. " ...their true nature which was not human, but nymphic (that is, demoniac)...” Appel offers an ample gloss of nymphic, discussing the role of nymphs in Greek and Roman mythology, as well as the term ’ s scientific meaning, but leaves, alas, its initial meaning out of account—nymph, or nympha is Greek for “bride.” Appel also leaves the demon in the parenthesis out of account. Humbert’s choice of adjective is

[11]

obscure (the term is used by Chaucer, Milton and as late as Hazlitt, but had become quite rare in the 1950s). Humbert does not seem to have chosen it simply in keeping with his taste for archaism, but also for more programmatic reasons. The demon in question, given the Greek reference (nymphic) which precedes it, would not be devilish or demonic in the sense we think of today (and which we would usually denote as demonic). This demon, or better daemon, would be, as the OED describes such, “a supernatural being of a nature intermediate between that of gods and men; an inferior divinity, spirit, genius”—which is more in line with how Humbert conceives of Lolita—impish, mischievous, even otherworldly—but not evil.

22. “Oui, ce n ’est pas bien.” This French phrase means not, “Yes, that is not nice,” (cf. note 22/3), but, “Yes, that is not good.”

23. “...qui pourrait arranger la chose...” This means not “who could fix it” (Appel note 23/3), but, “who could arrange it” (there is no state of affairs which needs to be rectified—and this is not the meaning of the phrase). If one wants to retain Appel’s formulation, one might say, “who could fix it up," though that idiom does not correspond to the simplicity of the French phrase.

43. “Monday. Delectatio morosa. I spend my doleful days in dumps and dolors.” Appel offers the following note to this passage: “Latin; morose pleasure, a monastic term” (AL, 357; note 43/2). Delectatio morosa is indeed Latin and is indeed a monastic term, but does not mean morose pleasure. The term is part of the technical vocabulary of Christian doctrine. Delectatio morosa is pleasure taken in sinful thinking without desiring it, and is thus classified alongside of gaudium, dwelling with complacency on sins already committed, and desiderium, the desire for what is sinful, as “internal sins” in Catholic orthodoxy (since Aquinas). That Humbert’s sin is at this point only “internal” is not irrelevant to the story he tells.

[12]

44/1. “ne montrez pas vos zhambes.” Appel correctly translates this but does not note that Charlotte’s remark to her adolescent daughter is with the formal, revealing not only her accent but her French to be a sham (no mother would use the formal to her adolescent daughter).

70/2. “peine forte et dure.” Appel offers the translation, “strong and hard torture.” Translated literally into today’s French the term means “hard and severe punishment.” Humbert’s use of it is clarified when we note that the term is from French (Norman) Law (adopted eventually by English Law and abolished in the Felony and Piracy Act of 1772) denoting a punishment applied to prisoners who refused to plead and which involved placing heavy weights upon them. It bears noting that the phrase is found in Poe’s “William Wilson” (“In a remote and terror-inspiring angle was a square enclosure of eight or ten feet, comprising the sanctum, ‘during hours,’ of our principal, the Reverend Dr. Bransby. It was a solid structure, with massy door, sooner than open which in the absence of the ‘Dominic,’ we would all have willingly perished by the peine forte et dure.”) as well as in Baudelaire’s discussions of Poe’s childhood. In his first and rarely reprinted biographical introduction to Poe’s works, “Edgar Poe, sa vie et ses ouvrages” (from 1852), Baudelaire, wishing to illustrate certain aspects of Poe’s childhood, cites at some length Poe’s tale “William Wilson” in his own translation and this passage in particular (cf.Charles Baudelaire Œuvres complètes. Two volumes. Edition de la Pléiade. Ed. Claude Pichois. Paris: Gallimard, 1976. 11.256). This passage is not reproduced in Baudelaire’s later and better known essay “Edgar Poe: sa vie et ses œuvres” (1856), where along with the slight change in title Baudelaire reworks the majority of his material.

72/1. “’The orange blossom would have scarcely withered on the grave,’ as a poet might have said.” Appel calls this a parody of a ‘poetic’ quotation,’ which it is, but he does not note its import: orange blossoms traditionally represent marriage and

[13]

form part of the bride’s accoutrement. Orange blossoms play a prominent role in Nabokov’s beloved Madame Bovary.

89/1. “Cavall and Melampus.” These are the names of the Farlows’ dogs. Appel writes: “’Cavall’ comes from cavallo (a horse), and ‘Melampus ’ from the seer in Greek mythology who understood the tongue of dogs and introduced the worship of Dionysus” (AL, 373). “Cavall” does come from cavallo. And Melampus is indeed a figure from Greek mythology. He is not a seer though. His gift is that he understands the language of nature. In the most oft-repeated story about Melampus, serpents lick his ears and he thus acquires the capacity of understanding the speech of all creatures (cf. The Odyssey 11.290 ff). Dogs are nowhere isolated for special consideration and there appear to be no extant references to Melampus understanding the language of dogs (the most common stories involve birds, snakes and worms [the latter informing Melampus that a building was about to crumble]).

But it is not this Melampus which gives Byron’s, and consequently the Farlows’, dog its name. There is another Melampus who simply is a dog. One finds a reference in Ovid to Melampus as one of Acteon’s dogs (Ovid Metamorphoses III.206). Appel, or his source, appears to have conflated the two stories. (As for the identity of this source. Neither The Oxford Classical Dictionary (Ed. N.G.L. Hammond and H.H. Scullard. 2nd edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1970. 666) nor the far more comprehensive Paulys Realencylopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft. Munich: Alfred DruckenmüllerVerlag, 1931 (reprinted 1984), which contains a 13-page article on “Melampus ” (Volume XV. 1, pps. 392-405), indicate the source of Appel’s supposition. As for Cavall (or Cafal), it was the name of King Arthur’s hunting dog.

[In the original annotation of the first photostat version which Appel submitted to Nabokov, Appel writes: “Charlotte ’ s dogs [they are not Charlotte’s dogs LD] are named after Edith

[14]

Louisa Cavell (1865-1915), the celebrated English nurse executed by the Germans during World War I, and Melampus, from Greek mythology, a seer who, among other things, cured the daughters of Proteus of a madness induced by Dionysos.” Nabokov does not correct the error in ownership of the dogs (though this is corrected before the book goes to print), but does note that the allusion is to the names of Byron’s dogs, that Cavall comes from cavallo (horse) and that Melampus “understood the tongue of dogs” and crosses out the rest.]

120/2. “spoonerette.” Humbert’s neologism refers not to spoonerisms nor to “necking” but to the position of Humbert and Lolita’s bodies, Lolita with her back against Humbert’s chest, fitting snugly as two spoons placed one upon another would fit. The “-ette” refers to Lolita’s diminutive size.

158/2 and 158/3. Humbert, moving north, would not first observe San Francisco then “the coastline of Monterey” as Monterey is due south of San Francisco (Appel; AL, 391).

224/2 un ricanement. Appel translates this as “sneer.” It is instead a contemptuous laugh or snicker. “I told myself with a burst of furious sarcasm—un ricanement—that I was crazy to suspect her...”(AL, 224). Humbert is laughing contemptuously here, not sneering.

258 “She was so kind, was Rita, such a good sport, that I daresay she would have given herself to any pathetic creature or fallacy...” The pathetic creature is of course Humbert. The “pathetic fallacy” is at least two things. Humbert, down on his luck and on himself, sees himself as a pathetic and fallacious creature. The “pathetic fallacy” is an allusion to a common term from the technical vocabulary of aesthetics. It was coined by John Ruskin(in 1856) and means, “the attribution of human emotion or responses to animals or inanimate things, esp. in art and literature” (OED). The reader would probably be right to hear an additional note in the remark: a ribald reference to Rita’s loose lifestyle, as it seems Humbert is speculating that

[15]

she would have given herself sexually to just about any pathetic creature or on the basis of any pathetic fallacy.

259/3. Schlegel. Friedrich Schlegel is not necessarily the one who is being referred to here. His equally if not more famous brother August Wilhelm, whom Nabokov writes of in his notes to his critical edition of Eugene Onegin, is just as likely a candidate.

302/5. “Clare the Impredictable.” Appel classifies this as a “portmanteau word’" (after Lewis Carroll), which is correct, but credits Nabokov with its authorship, which is not. In Chapter 17 of Ulysses, Joyce refers to the “extermination of the human species, inevitable but impredictable” (Ulysses. Gabler Edition. New York: Vintage, 1986; 556; 17.465).

307. “A kind of thoughtful Hegelian synthesis linking up two dead women.” At this moment in the story Humbert has just bumped to a stop, in a field, observed by approaching policeman. Appel treats his reader to a longish note where we read that the two women in question are Charlotte Haze and Lolita: “the death of Charlotte is remembered here...blending with the whole story of Lolita, from the cows on the slope (p.112) to her assumed death”(AL,450). Somewhat irrelevantly, Appel continues: “This ‘Hegelian synthesis’ realizes Quilty’s ‘Elizabethan’ play-within-the-novel. The Enchanted Hunters, which featured Lolita as a bewitching ‘farmer’s daughter who imagines herself to be a woodland witch, or Diana’ (p. 200), and seven hunters, six of them ‘red-capped, uniformly attired’” (ibid.). Appel concludes that, “when Humbert asks a pregnant and veiny-armed Lolita to go away with him, he demonstrates that the mirage of the past (the nymphic Lolita as his lost ‘Annabel’) and the reality of the present (the Charlotte-like woman Lolita is becoming) have merged in love, a ‘synthesis linking up two dead women’” (ibid.). This is energetic but faulty reasoning. The first woman is indeed Charlotte, and the passage on page 97 shows this clearly as the vehicle of her destruction bumps similarly to a stop on an incline. The second

[16]

woman however is not Lolita (Appel’s evidence is that during an early drive Humbert notes cows on a hillside and Lolita informs him, “I think I’ll vomit if I look at a cow again” [AL, 112]). Some twenty pages earlier, Humbert recounts “Ramsdale revisited” and his visit to Charlotte’s grave. During his stroll through the graveyard Humbert recalls and recounts the case of “G. Edward Grammar, a thirty-five-year-old New York office manager who had just been arraigned on a charge of murdering his thirty-three-year-old wife, Dorothy. Bidding for the perfect crime, Ed had bludgeoned his wife and put her into a car. The case came to light when two county policeman on patrol saw Mrs. Grammar’s new big blue Chrysler...speeding crazily down a hill, just inside their jurisdiction....The car sideswiped a pole, ran up an embankment covered with beard grass, wild strawberry and cinquefoil, and overturned...It appeared to be a routine highway accident at first. Alas, the woman’s battered body did not match up with only minor damage suffered by the car. I did better” (AL, 287-288). Humbert’s reference, easy to misunderstand, is a macabre reference to what he refers to for the first time, if indirectly, as his “murder” of Charlotte (Humbert, another husband “bidding for the perfect crime,” has done better in the disposal of his wife). The “synthesis linking up two dead women” is formed by one woman who was killed by a car that then rolled up to a stop on an embankment (Charlotte), and another was killed and then placed into a car which rolled up onto an embankment. It is highly unlikely that Humbert means Lolita as this second woman (baroquely fused with her mother in Appel’s strange description), because he does not envision her as dead, and he goes to great lengths, up to and in the last lines of the novel, to stress how he feels she is still a part of “blessed matter” (AL, 309). The photostat version has a deleting line in Nabokov’s hand through the initial version of this note accompanied by comments which are illegible.

[17]

311. “ The first little throb of Lolita went through me late in 1939 or early in 1940, in Paris, at a time when I was laid up with a severe attack of intercostal neuralgia. As far as I can recall, the initial shiver of inspiration was somehow prompted by a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes, who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature’s cage.” Appel notes the importance of this “prison trope.” Of this supposedly real source he says nothing. What then of this article which inspired Nabokov? Might it teach us anything about the process of his inspiration? As such, it may not—as it does not exist. The newspapers for those years have been combed and recombed but the article has not been found. And it seems that there is a good reason for this. The most thorough annotator of Nabokov’s work in any language is the editor of the German critical edition of his works, Dieter Zimmer. In Zimmer’s exhaustive note to the passage in Nabokov’s essay where he refers to this inspiring article, Zimmer notes the various researches undertaken by him and others to find any such article in the newspapers of those years. More recently, Nabokov’s son and literary executor Dmitri Nabokov noted that he knew nothing of the article’s whereabouts and confirmed the fact that neither he nor anyone else had to his knowledge laid hands upon it (Email of Wednesday, November 13,20025:51 AM. To be found on the Nabokov Archive List Serve. Nabokov List-Serve: http://listserv.ucsb.edu). Zimmer notes that the celebrated zoologist Desmond Morris published an exhaustive list of all known experiments conducted with primates involving drawing or sign making. Nabokov’s ape is nowhere to be found therein (cf. Vladimir Nabokov. Lolita. Rowohlt: Reinbek bei Hamburg, 1995; pps. 686-687. Cf. also Desmond Morris. The Biology of Art (New York: Knopf, 1962). Zimmer also directs his reader’s attention to the claims of the reputed primatologist David Premack in his The Mind of an Ape to the effect that

[18]

though apes do not lack the motor skills to produce drawings, they seem to lack the mental skills for such complex depictions (Premack, 1983, 108ff.; cited Zimmer, ibid.). As another observer has noted, they can, however, take pictures. In a letter from October 26,1998, Nabokov bibliographer Michael Juliar noted the following: “Life magazine, on page six of its 5 December 1949 issue, published most of a Nabokov letter about butterfly wings in Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Delights [cf. SL, 93-94]. On the facing page, seven, is a letter about the first photograph ever taken by an ‘ape.’ Mr. (or Mrs. or Miss) Clark writes, ‘Photographer Bernard Hoffman’s Cookie (Life, Nov. 14) was not the first ape to take a picture. My protégé, whose name was also Cookie, was an advanced shutterbug more than seven years ago when an article appeared in This Week magazine Oct. 11, 1942.’ Accompanying the letter are two photographs, one of the ‘first Cookie’ examining a box camera (a Kodak brownie?), and one of humans looking into Cookie’s cage, taken, of course, from Cookie’s point of view. The bars of the cage stand out more than the human heads. On page ten, the letters continue with one pointing out that Life had published similar photos in its “Pictures to the Editors” on 5 September 1938. He says, ‘...you showed two pictures taken by a chimpanzee in a Berlin zoo. ’ Life reprints the two photos. If both were actually taken by the chimp, as the letter says, the first photo is of another chimp holding a manmade object. The second is of people staring (chimps point of view) into a cage. Again, the bars of the cage are clearly visible. Is it possible that Nabokov was referring to one of these three sets of photos: one published in 1949, one in 1942, and one in 1938, all published in the US?” This letter to be found at http:/ /listserv.ucsb.edu/lsv-cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind9708&L=nabokv-1&P=R2114). In summary, writes Zimmer, “this article about the incident in Paris’ Zoo has despite extensive efforts never been uncovered and is perhaps a fiction” (Zimmer, ibid.).

[19]

There is another phrase which merits noting here: “intercostal neuralgia”— a burning pain between the ribs. He would not be the first, as this is indeed what our first father is said to have felt when he passively provided life for a woman. It is possible that this wry symptom is meant to suggest to us that the pangs in question were those of creation.

Appendix: Brian Boyd’s Annotations to the Library of America Edition

Vladimir Nabokov. Novels: 1955-1962. New York: Library of America, 1996.

There are two points in Boyd’s more spare notes to Lolita that might be clarified. Both concern sexual matters. Boyd’s note for “merkin” is incorrect (cf. p. 875). Boyd glosses the word as meaning, “false hair for the female genitalia.” From the 16th to the 18th century merkin referred to “the female pudendum.” Its modem sense is “an artificial vagina.” Merkins were and are often equipped with such decorative “wigs,” but that is not the primary sense of the word nor is it the sense Humbert is employing in his reference to his first wife.

Boyd’s note glossing Humbert’s reference to Ronsard’s “Je te salue o vermeillete fante” (which Humbert modernizes as “fente”) presents a small inaccuracy. The final term would be better translated as “cleft” rather than the “slit” which one finds in both Boyd’s annotation and Appel’s. (The first photostat draft of Appel’s annotations translates the passage as “crevice,” which Nabokov changes to “slit,” which Appel then employs and Boyd adopts.) What neither annotator notes is that this is not the title but the first lines of a poem by Ronsard. The poem, whose title is “LMF.,” went unpublished from 1619 to 1919 and is from Ronsard’s Livret de folatries (first published in 1553). (It was removed from the edition of l560, replaced for the 1584 edition and the successive editions up until 1619 before being omitted from every edition of Ronsard’s work until that of 1919.) Boyd and Appel cite its source as the “Blason du sexe

[20]

feminin.” This work, if it exists, is an extremely rare one (evidence of which is that the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, possessing a depôt légal on every work published in France since the 16th century, neither possesses the work nor has any record of it). In any event, if this work exists it is not a work by Ronsard, as Appel and Boyd both indicate, nor was it the work in which the poem was first published, but an anthology or reference work of some sort. Boyd, who appears to take his note from Appel repeats the errors of that note along with an addition. He defines the term blason, as “a short poem in praise or criticism of a certain subject,” which is not correct. A blason is such a poem in praise of a certain subject. A poem in “criticism” of a certain subject is a “contre-blason." To be absolutely precise, however, as Nabokov, in his notes and elsewhere was so fond of being, Ronsard’s poem is neither, but instead belongs to the genre “blason anatomique.”

—Leland de la Durantaye, Cambridge, Massachusetts

HIPPOPOTAMIANS IN ARDIS

Incorporating myriad puns, anagrams and coded allusions, Ada is the most playful of Nabokov’s novels. And while literary playfulness—even Nabokov’s literary playfulness—is often dismissed as unserious (if not juvenile), most of Ada’s “jokes” are deeply serious. Of Ada’s many jokes, few are more serious than a certain throwaway pun delivered by Van Veen.

Chapter Fourteen of Ada’s first part locates the Veens in the garden at Ardis, having tea. As tea is served, the Veens’ neighbor Greg Erminin arrives, his arrival the spur that kick-starts a wide-ranging discussion of religion. As the conversation leaps between topics—from Judaism to dietary laws to crucifixion—eight-year-old Lucette grows increasingly

[21]

confused. Finally, unfamiliar with a long word, she turns to her cousin Van for help:

Lucette was puzzled by a verb Greg had used. To illustrate it for her, Van joined his ankles, spread both arms horizontally, and rolled up his eyes.

“When I was a little girl,” said Marina crossly, “Mesopotamian history was taught practically in the nursery.”

“Not all little girls can learn what they are taught,” observed Ada.

“Are we Mesopatamians?” asked Lucette.

“We are Hippopotamians,” said Van. (91)

Ada is rife with quips like Van’s portmanteau “Hippopotamians,” and one suspects that critics who posit the novel’s playfulness as distracting (or worse) have such quips in mind. If at first— even second—glance, Van’s quip appears a silly cast-off, disclosive only of a compulsion to juggle sounds, understood within a broader context the pun becomes a concise iteration of the lopsided love-triangle described in Ada.

A subtle pattern of interwoven details locates Van and Ada, as lovers, in the Mesopotamia crossly mentioned by Marina. If Mesopotamia is, etymologically, the “land between two rivers,” Van and Ada, in their efforts to thwart Lucette’s curiosity, repeatedly visit“Caliph Island”(406),a lush isle in the middle of the bi furcating Ladore River. Moreover, if Mesopotamia, where ancient Babylon was situated, is often referred to as Babylonia, not only are three “Babylonian Willows” growing on Caliph Island (216), but a “Babylonian butterfly” appears at the “forest fork” where Van and Ada separate following their first summer together (158). And finally, if the Biblical Garden of Eden is placed by tradition in Mesopotamia, beside the Shattal River (formed of the confluing Tigris and Euphrates rivers), Van and Ada share their first intimate moment while Ada is climbing a “Shattal Tree,” (78), a tree later referred to as both the “tree of

[22]

Eden,” (401) and as a “Tree of Knowledge” imported from “Eden national park” (95). Within the world of Ada, then, the word “Mesopotamia” resonates powerfully, alluding not only to the Edenic love of Van and Ada, but also to the lovers’ removal from mundane affairs. If any of Ada's characters may be designated “Mesopotamians,” they are Van and Ada. That said, Lucette and Van are. Van’s quip hints, “Hippopotamians.” What might this mean?

In ancient Greek, “hippopotamus” means “river horse.” And just as a web of detail locates Van and Ada in the Edenic area of Mesopotamia, so two overlapping patterns place Lucette, like an ungainly hippopotamus, in an archetypal river. One pattern presents Lucette as a mermaid (for example, apologizing to Lucette for an attempt to enroll her in his and Ada’s sexual games, Van writes: “We are sorry you left so soon. We are even sorrier to have inveigled our Esmerelda and mermaid in a naughty prank" (421). Furthermore, Van, referring to Lucette ’ s successful attempt to induce Ada to return to himself, writes of “a mermaid’s message” (562)). Another pattern associates Lucette with Shakespeare’s Ophelia (“ ‘For the sweet all is sweet,’” quips Van when Lucette recalls a waiter’s kindness (481), while in a letter to his father written after Lucette’s death, Van likens Lucette’s situation to that of Ophelia: “As a psychologist, I know the unsoundness of speculations as to whether Ophelia would not have drowned herself after all, without the help of a treacherous sliver, even if she had married her Voltemand” (497)). The Ophelia pattern, moreover, incorporates a portentous mishap from 1884, when Lucette, a red-head, has her red-haired doll swept away by a current as she is bathing it in the Ladore River (143). Thus, just as Van and Ada are, when together, “Mesopotamians” alone in the garden of Eden, so Lucette, as Van’s quip suggests, is a “Hippopotamian,” immersed in an aqueous, and so potentially fatal, environment. Having discerned two textual patterns, one locating Van and Ada in the Garden of Eden, the other plunging

[23]

Lucette into an archetypal river, we get a sense of the opulent textual fabric embellished by Van’s “Hippopotamians” pun. Yet full appreciation of the pun is premised upon relating one pattern to the other.

The key link is topographical. If Van and Ada are linked with Mesopotamia, Lucette is immersed in a figurative river. This suggests that Lucette, struggling to join Van and Ada in Eden, may be floundering towards a destination where she does not belong. Evidence for this reading arrives late in the novel, as Lucette, alone with Van aboard the ocean liner Admiral Tobakoff, appears to arrive in Eden, only to find paradise befouled.

They were now reclining on a poolside mat face to face, in symmetrical attitudes, he leaning his head on his right hand, she propped on her left elbow. The strap of her green breast-cups had slipped down her slender arm, disclosing drops and streaks of water at the base of one nipple. An abyss of a few inches separated the jersey he wore from her bare midriff, the black wool of his trunks from her soaked green pubic mask. The sun glazed her hipbone; a shadowed dip led to the five-year-old trace of an appendectomy. Her half-veiled gaze dwelt upon him with heavy, opaque greed, and she was right, they were really quite alone. . . He accepted the touch of her blind hand working its way up his thigh and cursed nature for having planted a gnarled tree bursting with vile sap within a man’s crotch. Suddenly Lucette drew away, exhaling a gentle “merde.” Eden was full of people.

Two half-naked children in shrill glee came running toward the pool. A Negro nurse brandished their diminutive bras in angry pursuit. Out of the water a bald head emerged by spontaneous generation and snorted. (478)

[24]

The emergence of a bald and snorting head, spontaneously generated beneath the surface of the swimming pool, underscores the fact that Van and Lucette will remain “Hippopotamians,” river-beings, swimming towards Eden but never arriving. And indeed, immediately after the emergence of the Hippopotamus-like head, a “tall splendid creature” (479) appears poolside, “Miss Condor” (481), the punningly-named mechanism with which Van later fends off Lucette’s last, desperate advance. As it turns out, of Ada's, three protagonists, only two, Van and Ada, belong in Eden. Seemingly a frivolous collision of words, Van’s pun, once analyzed in a broader context, is a precise iteration of the unstable love-triangle mapped in Ada. Just as “Hippopotamians” fuses “hippopotami” and “Mesopotamians,” so Lucette, struggling to join Van and Ada in a figurative Garden ofEden, has one foot in Mesopotamia and one in a river.

Tracing the two patterns fused in Van’s throwaway pun reveals the risk inherent in dismissing any of Nabokov’s jokes as frivolous fun. Which is not to say the pun is only serious. Van’s humor—like Nabokov’s—is first of all humorous, and here the humor lies not just in the word-play but also in the linking of slender Lucette and acrobatic Van to an ungainly hippopotamus. Of course, strictly speaking the beast in question is not a hippopotamus at all, being instead a hippopotamian, Ardis’s most interesting animal, a marvelous hybrid which, for all we know, is as graceful as a gazelle.

—Matt Brillinger, Ottawa, Ontario

REMBRANDT’S DEPOSITION FROM THE CROSS IN

THE GIFT

Rembrandt, the quatercentenary of whose birth was celebrated last year, and his art are frequently referred or

[25]

alluded to in Nabokov’s works. For example, King, Queen, Knave contains references to “the air of Rembrandt” and “the brightest Rembrandtesque gleam” (KQK 91 and 154) and “The Visit to the Museum,” similarly, to “a copper helmet with a Rembrandtesque gleam” (Stories 282). The latter phrase brings to mind such paintings by or attributed to Rembrandt as The Man with the Golden Helmet (ca. 1650, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin); Mars (1655, Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow), and its assumed pendant Pallas Athena (1663, until 1930 in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg; presently in the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon)—the latter two also each known as Alexander the Great. And in Ada, Nabokov metaphorically and most succinctly conveys the essence of Rembrandt’s art that outweighs many volumes written on the illustrious Dutchman: “Remembrance, like Rembrandt, is dark but festive” (Ada 109).

In addition to these generic references that suggest Rembrandt’s predilection for the interplay of light and shadow as well as the spirituality of his celebratory art, Nabokov points to specific works by the Dutch master. Thus, Rembrandt’s Christ at Emmaus, also known as The Pilgrims at Emmaus, or Supper at Emmaus (1648, Musée du Louvre, Paris), is mentioned in Pnin. In this novel, a “reproduction of the head of Christ” from this painting, “with the same, though slightly less celestial, expression of eyes and mouth” (Pnin 95), hangs in the studio of Lake, Victor’s art teacher. Twenty years earlier, Nabokov alluded to Christ’s countenance in this painting in the description of Cincinnatus’s face when speaking of “the light outline of his lips, seemingly not quite fully drawn but touched by a master of masters” and “the dispersing and again gathering rays in his animated eyes” (IB 121).

Another reference to a particular work of Rembrandt can be found in The Gift. In his Life of Chernyshevski, Fedor Godunov-Cherdyntsev, the protagonist and narrator of the novel, sarcastically notes that biographers viewed the author of What Is To Be Done as “Christ the Second” and

[26]

mark[ed] his thorny path with evangelical signposts /...../ Chernyshevski’s passions began when he reached Christ’s age. Here the role of Judas was filled by Vsevolod Kostomarov; the role of Peter by the famous poet Nekrasov, who declined to visit the jailed man. Corpulent Herzen, ensconced in London, called Chernyshevski’s pillory column “The companion piece of the Cross.” And in a famous Nekrasov iambic there was more about the Crucifixion, about the fact that Chernyshevski had been “sent to remind the earthly kings of Christ.” Finally, when he was completely dead and they were washing his body, that thinness, that steepness of the ribs, that dark pallor of the skin and those long toes vaguely reminded one of his intimates of “The Removal from the Cross”—by Rembrandt, is it? (Gift 215; italics are Nabokov’s)

While, as the passage indicates, Fyodor is not quite certain who painted the canvas in question, Nabokov, the true creator of the novel, is fully aware of Rembrandt’s authorship and employs the “by Rembrandt, is it?” phrase as an emphatic, attention drawing device.

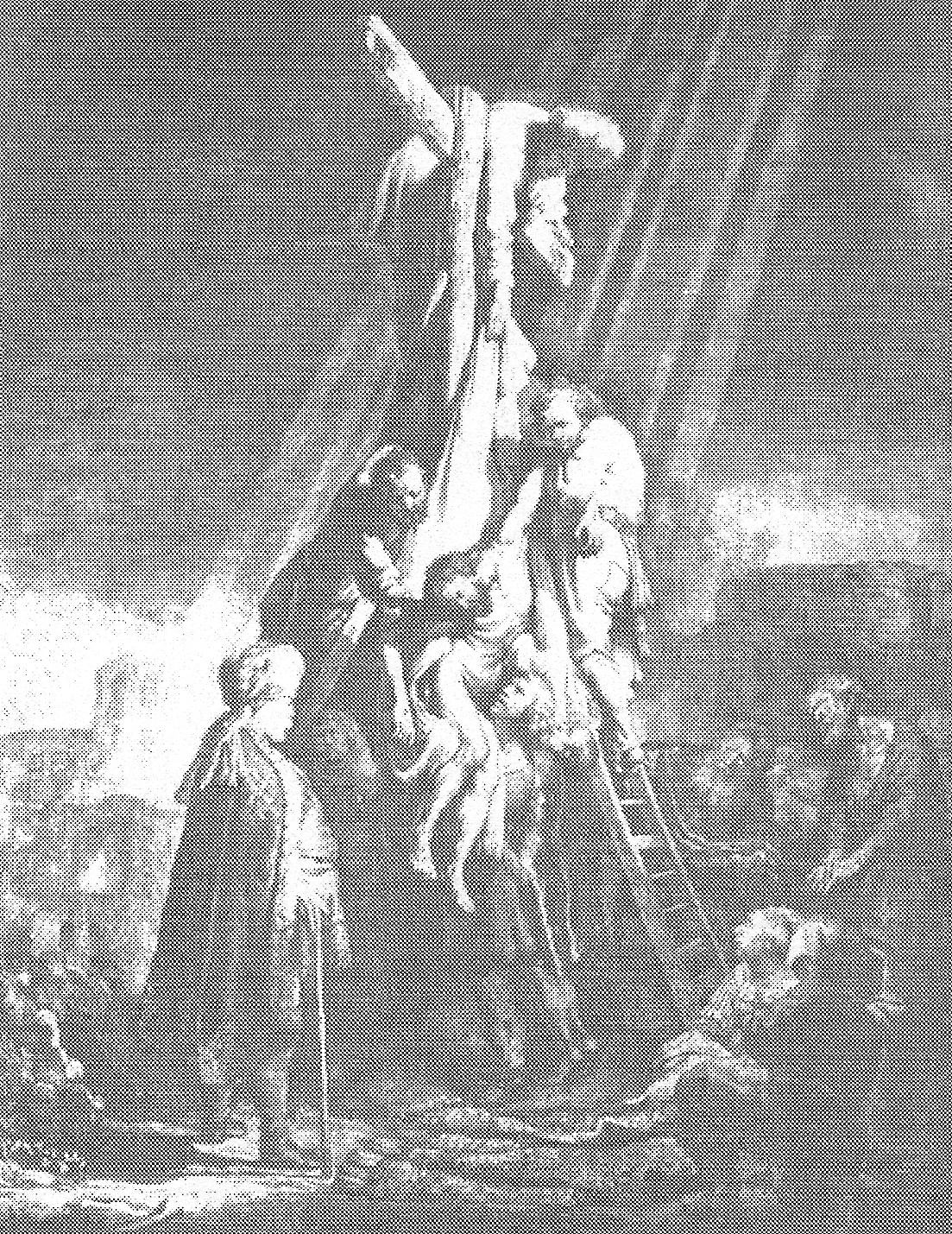

There are at least five versions of Rembrandt’s The Deposition [Descent] from the Cross to which Fyodor hesitantly refers here: three paintings, one located at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the other at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg (both date from 1634), and the third at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC (ca. 1651), and two etchings (1633) (Fig. 1) and The Descent from the Cross by Torchlight (1654). Knowing Nabokov’s penchant for the authorial presence, it is most likely that he had the earlier etching in mind—the only variant that contains a person evidently bearing the artist’s easily recognizable features. It is of course the individual standing on the ladder and supporting Christ’s left arm. To Nabokov’s choice points the phrase “those long toes,” which look more prominent in the etching. This assertion is also

[27]

Fig. 1

[28]

Fig. 2

[29]

validated by the novel’s description of the work of art as depicting “dark pallor of the skin” and “steepness of the ribs” that appear more pronounced in the etching in which the body of Jesus is lit with somewhat dim and suffused backlighting. In the paintings, on the other hand, the body of Christ is shown in brighter light and therefore does not give this impression. The later etching does not match Nabokov’s description either, since “steepness of the ribs” is obscured by one of the individuals lowering the corpse of Jesus.

Nabokov’s mention of Rembrandt’s Deposition from the Cross, presumably the earlier etching, most likely implies the writer’s authorial presence in the novel. Furthermore, when referring to The Deposition from the Cross, Nabokov apparently also intended to invoke The Raising of the Cross (1633, Alte Pinakothek, Munich), to which the earlier version of The Deposition from the Cross served as the pendant (Fig. 2). In The Raising of the Cross, Rembrandt portrayed himself once again, but this time as the soldier who helps to lift the cross, to which the body of Jesus is nailed. (Rembrandt painted both works as part of the Passion series for Prince Frederick Henry of Orange.) By juxtaposing these two pieces in which Rembrandt assigned such diametrically opposing roles to his own image, one may conclude that the artist, in all likelihood, wished to convey the message of collective human guilt, including his own, for the death of Jesus. At the same time, he evidently wished to show penitence when depicting himself as the sorrowful figure, in anguish, that helps lower Christ’s corpse from the Cross. By mentioning Rembrandt’s Deposition from the Cross and by invoking his Raising of the Cross, Nabokov seems to suggest a more humane role for his protagonist who is credited with the authorship of the novel about Chernyshevski’s life.

Earlier in The Gift, Nabokov teaches Fyodor a lesson against stereotyping. Upon riding a tram, Fyodor is seized with prejudice against Germans, even though it was, “he knew, a

[30]

conviction unworthy of an artist” (Gift 80). When another passenger boards the tram, Fyodor directs his hostile thoughts toward this man, discovering his more and more unattractive, “typically German,” features. While Fyodor “threaded the points of his biased indictment, looking at the man who sat opposite him,” all of a sudden, the fellow passenger took a copy of the Russian émigré newspaper from his pocket “and coughed unconcernedly with a Russian intonation” (Gift 82). Fyodor fully comprehends the message that life, or better to say, his creator sends him: “That’s wonderful, thought Fyodor, almost smiling with delight. How clever, how gracefully sly and how essentially good life is!” (ibid.). This earlier ethical lesson prepares Fyodor for a more complex and benevolent perception of the world, so important not only in his task of writing the Chernyshevski biography but also “the autobiography,” something he will be “a long time preparing” (Gift 364).

The reference and allusion to Rembrandt’s two Biblical pieces shed light on Fyodor’s, and Nabokov’s own, dual approach to “Christ the Second”: on the one hand, the protagonist exhibits disdain toward Nikolai Chernyshevski (1828-89), a philosopher, writer, and aesthetician; and on the other, he demonstrates compassion when admiring Chernyshevski’s personal courage and the steadfastness of his beliefs. Thus, Fyodor “began to comprehend by degrees that such uncompromising radicals as Chernyshevski, with all their ludicrous and ghastly blunders, were, no matter how you looked at it, real heroes in their struggle with the governmental order of things” (Gift 202-3). This dual approach clearly reflects Nabokov’s own attitude toward Chernyshevski, “whose works,” as he puts it, “I found risible, but whose fate moved me more strongly than did Gogol’s” (SO 156). Nabokov, the creator of both Fyodor and Chernyshevski, warns against pigeonholing and a superficial, schematic approach to life, which Fyodor, his alterish ego, learns to recognize. In so doing, the writer advocates “mercy toward the downfallen” (EO, 2:311) in the compassionate

[31]

tradition of Pushkin, whom he revered, and in accordance with the best liberal convictions of his own family. In the spirit of Rembrandt’s Passion masterpieces, Nabokov teaches the reader to be more benevolent and to seek redeeming features in every fellow human, no matter how “risible” the person may appear.

—Gavriel Shapiro, Ithaca, New York

AN ADDITIONAL SOURCE FOR A CENTRAL ASIAN EPISODE IN THE GIFT

The second chapter of The Gift is forever dear to all whose life and research is connected to Central Asia, this author being no exception. One of the most memorable moments of this chapter is the ghost-like image of two Americans crossing the Gobi desert on bicycles, met by Konstantin Godunov-Cherdyntsev in 1893 in their “Chinese sandals and round felt hats.”

Real-life travel sources for The Gift are revealed in Dieter E. Zimmer’s wonderful 2006 book (Nabokov reist im Traum in das Innere Asiens, Rowohlt), as well as the earlier article by Zimmer and Hartmann (The Amazing Music of Truth: Nabokov’s Sources for Godunov’s Central Asian Travels in The Gift; Nabokov Studies, 2002/2003,7:33-74). This work painstakingly demonstrated how Nabokov—in a manner reminiscent of Jules Verne—incorporated in his novels, often verbatim, documentary information from famous travelers’ books, resulting in “some of the finest, most evocative prose Nabokov ever wrote” (Zimmer and Hartmann, p. 33).

Among many others, Zimmer and Hartmann (p. 52) uncovered the very real background of the bicycling Americans episode, which is completely authentic. Thomas Gaskell Allen and William Lewis Sachtleben, two 1890 graduates of Washington

[32]

University, St. Louis, “decided to put a practical finish to their theoretical education.” In 1890-1892, Allen and Sachtleben rode over 15,000 miles through Europe, Asia, and North America, at that time the “longest continuous land journey ever made around the world.” Their travel included almost 7,000 miles trek across Turkey, Persia, Turkestan and northern China, described in their charming small book, Across Asia on a Bicycle: The Journey of Two American Students from Constantinople to Peking, published in 1894 by The Century Co., NewYork. This book is also now available in a new edition with additional notes and materials (Inkling Books, Seattle, 2003, ed. Michael W. Perry).

Zimmer’s 2006 book gives a German translation (pp.101-110) of several pages from Allen and Sachtleben (1894, pp. 181-194, orpp. 121-130 in 2003 edition), specifically dealing with the Gobi portion of their journey in summer 1892. A spectacular photograph from the frontispiece of their 1894 book is reproduced in both Zimmer and Hartmann (2003, fig. 5) and Zimmer (2006), featuring Allen and Sachtleben with their bicycles on their arrival in Peking. The travelers are clad in “Chinese sandals and round felt hats” as mentioned by Nabokov. The picture is available online at: http://www.dezimmer.net (“Bilderalbum” slide 7). The same photograph is found on the cover of2003 Allen and Sachtleben edition as well as on its page 12.

There is, however, another source for the Allen and Sachtleben episode, not mentioned by Zimmer. It can be found on an important website Zerkala, the database of sources on Central Asia maintained by the University of Halle (Germany) (Dr. Juergen Paul). The website features a small article (http:/ /zerrspiegel.orientphil.uni-halle.de/i43.html) from the popular Russian journal Niva dated 1893, No. 3(1): 66-68, which is a correspondence from China about Allen and Sachtleben’s arrival in Peking. The travelers’ passage through Russian territory is briefly described, including their visit in Askhabad

[33]

(now Ashgabat, Turkmenistan) to the military governor General Kuropatkin (the same Kuropatkin mentioned in the famous match episode in both Speak, Memory and Drugie berega).

Most important, the Niva article mentions the travelers’ “Chinese sandals” (“kitaiskie sandalii”) and “round felt hats” (“kruglye kitaiskie fetry”) in the exact same words used in Dar. This is hardly a coincidence; therefore Nabokov’s direct source for the Allen and Sachtleben episode was neither their 1894 book nor any other, but, obviously, the 1893 Niva article, which also features an engraving (“by Chelmicky,” a well-known engraver in Russia) made from the same photograph that was presented in Allen and Sachtleben’s book (1894, 2003) and reproduced in Zimmer and Hartmann (2003) and Zimmer (2006). The photograph was taken on their arrival in Peking (now Bejing) on 22 October 1892.

Zimmer and Hartmann (2003, p. 37) note “Chinese sandals, felt hats” in their list of “highly specific details.” Further, Zimmer (2006:263) suggests that Allen and Sachtleben donned these “chinesischen Sandalen und runden Filzhüten” specifically for this photograph. From the Niva 1893 article, however, we can see that it was not so. We are told that travelers changed into this Chinese attire in Manas (East Turkestan), on their way from Kuldja to Urumchi (today’s Yining and Ürümqi in Xinjiang Autonomous Region of China), soon after they crossed the Russo-Chinese border into Northwestern China. The Niva article specifically mentions how, in Manas, the travelers “zamenili svoyu obuv’ kitaiskimi sandaliyami i noskami, a furazhki kruglymi kitajskimi fetrami” (“exchanged their shoes for Chinese sandals and socks, and their caps, for round Chinese felt hats”). Allen and Sachtleben not only mention the Manas footgear change in their book but explain the reason for it: “With constant wading and tramping, our Russian shoes and stockings, one of which was almost torn off by the sly grab of a Chinese spaniel, were no longer fit for use. In their place we were now obliged to purchase the short, white cloth Chinese

[34]

socks and string sandals, which for mere cycling purposes and wading streams proved an excellent substitute, being light and soft on the feet and very quickly dried” (2003, pp. 113-114). (This author, with years of wading experience across Central Asian streams, wholeheartedly seconds the preference of sandals over Russian shoes.)

Thus Allen and Sachtleben’s appearance on crossing the Gobi desert indeed included this exotic foot- and headgear, exactly as seen by Konstantin Godunov-Cherdyntsev in Dar. The latter followed the same—and the only available—route of crossing from Russia to northwestern China (Kuldja – Manas – Urumchi), as reconstructed by Zimmer (2006).

Note that Nabokov confused the year of Allen and Sachtleben’s travel. Konstantin Godunov-Cherdyntsev meets them in 1893; however, in reality the travelers crossed the Gobi in August 1892. There is no obvious reason why the correct year should not have been given; it could be that Nabokov used the Niva journal date (1893) rather than details of the original 1892 itinerary.

Further, a very Nabokovian time- and theme-bending surprise comes from investigating the identity of the author of Niva 1893 article, signed just “I. Korostovets.”

This person is hardly a no-name: 27-year-old Ivan Iakovlevich Korostovets (1866-1933) was then a “second dragoman [translator]” in the very first Russian Imperial Embassy in Peking, mentioned as such by the famous geologist and traveler V. A. Obruchev in his well-known book, Ot Kiakhty do Kuldji. Both Obruchev and G. E. Grum-Grzhimailo met Allen and Sachtleben (Zimmer and Hartmann, 2003, p. 52).

A graduate of the famous Alexandrovsky Lyceum (Pushkin’s school, since 1882 under military authority), I. Ia. Korostovets went into diplomatic service in Asia, and was to become one of the last Imperial Ambassadors in China (1910-1912). He was also a well-known Orientalist, and wrote many books on Asia, among them Kitaitsy i ikh tsivilizatsiia (St.

[35]

Petersburg, 1896), Pre-War Diplomacy: The Russo-Japanese Problem (London, 1920), and Von Cinggis Khan zur Sowjetrepublik (Berlin, 1926).

Most interestingly, 12 years after Allen and Sachtleben’s journey Ivan Iakovlevich Korostovets was to become one of the two secretaries to Count Witte, the Russian Secretary of State, during the Portsmouth, New Hampshire peace treaty talks (1905), mediated by Theodore Roosevelt, which ended the Russo-Japanese war. The second secretary of Witte’s mission was Konstantin Dmitrievich Nabokov (also spelled Nabokoff) (1872-1927), the writer’s uncle.

Witte’s mission is depicted at the commemorative mural by William Andrew Mackay in Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), New York. There is a wonderful hallucinatory episode in both Speak, Memory and Drugie berega, in which V.V. Nabokov, in 1940, observes his surname written in Cyrillic characters as he goes down in the elevator in AMNH. The vision is immediately decoded for the reader: the name refers to K.D. Nabokov. Two other Cyrillic names on the mural are Witte and Korostovets. The name of Korostovets as the member of Witte’s mission on the AMNH mural appears in Drugie berega (Chapter 4): “on uchastvuet, vmeste s Witte, Korostovtsom i iaponskimi delegatami, v podpisanii Portsmutskogo mira” (“he [K.D. Nabokov] participates, along with Witte, Korostovets, and Japanese delegates, in signing of the Portsmouth Treaty.”). Korostovets, however, was not mentioned in the matching text of Speak, Memory.

Judging from this context, the name of Ivan Iakovlevich Korostovets, his diplomat uncle’s colleague, was well known to Nabokov. Ivan Iakovlevich, however, should not be confused with another Korostovets, Vladimir Konstantinovich (also spelled “de Korostovetz”), a journalist and a political figure in the London emigration, who is mentioned by both Brian Boyd in Russian Years and Andrew Field in Life in Part as having

[36]

employed both Vladimir and Vera Nabokov for translation work in 1924.

I would also like to comment on a very unusual use of the term “fetry” (“felt hats”) by Korostovets, reproduced by Nabokov after him. The modem Russian always uses the word “voilok” for traditional thick-felt products, and a felt hat of Central Asians is called “voilochnaia shapka.” Thinner and softer “fetr” (from French feutre) is a term reserved almost exclusively for the European-style, brimmed man’s hat, “fetrovaya shliapa” (such as worn by Busch when Fyodor meets him in the third chapter of The Gift).

Plural “fetry” for “felt hats” is never used in modem Russian (one dictionary even insists that “fetr” has no plural). It appears to have been used, however, in the 19th-early 20th century. Innokentii Annenskii (1855-1909), in his translation of Eurypides’ Iphigenia in Tauris, added a remark that Orestes and Pylades are dressed “po-dorozhnomu, v korotkikhplashchakh i fetrakh” (“travel-style, in short capes and felt hats”). Those are chlamys, a short traveling cape, and petasos, a brimmed felt hat with a low crown, so common among Ancient Greek travelers. In his own tragedy, Laodamia (1906), Annenskii also has a “Germes v fetre” referring to the winged petasos of Hermes. As M. L. Gasparov noticed, Valerii Briusov criticized Annenskii for his use of incongruent modem words, “fetr” specifically listed among them, in a Greek setting. The East Turkestanian hats worn by Allen and Sachtleben on their 1892 photograph are, however, not of the Orestes and Pylades style but brimless, flat-top, high-crowned affairs. Allen and Sachtleben’s headgear, documented in many photographs, varies throughout their book; they started with European colonial-style helmets, but “felt caps” are briefly mentioned on p.112 (2003 edition) as not giving much protection against the July sun.

Thus there is another precious reality thread woven in the rich tapestry of Dar. The forgotten 1893 words of the young Ivan Korostovets, the future witness of many great Asian

[37]

events, have been pinned by Nabokov, as a brief scientific diagnosis by Konstantin Godunov-Cherdyntsev, on two remarkable young Americans, describing them from head (round felt hats) to toe (Chinese sandals), and preserving their image in a mirage of the Gobi Desert.

I thank Don Barton Johnson and Stephen H. Blackwell for their suggestions on this note.

—Victor Fet, Huntington, West Virginia

INCEST AS A THEME OF LOLITA

“The theme of Incest makes its first major appearance in Nabokov’s English chef-d’oeuvre Ada, ” claims D. Barton Johnson in his fine article, “The Labyrinth of Incest in Ada, ” contained in his book Worlds in Regression (and in a different version in Comparative Literature, vol. 38 [1986], pp 225-254). This strong claim is overstated as it stands, as I shall attempt to demonstrate here.

“Round up the usual suspects”

From his first paragraph, Johnson emphasizes the important contribution made to Ada by Nabokov’s pervasive allusions therein to incest in other literary works. He reminds us that, “Nabokov wrote with an informed awareness of earlier literary treatments of his themes. Allusion to such predecessors is a hallmark of his style”(p 116). A principal function of such allusion is to include aspects of the work referred to in the referring work; lawyers call this sort of thing “incorporation by reference,” and it is a powerful literary device that Nabokov knew well how to use. We shall start by showing the pervasiveness of such references to the incest theme in Nabokov’s earlier “English chef-d’oeuvre” Lolita, noting first

[38]

the recurrent allusions in Ada to the incest theme in the works of Byron and Chateaubriand. Boyd labels this as “part of the literary subtext of Nabokov’s Ada ” (p. 119). In Lolita, Byron appears first in the famous class list (we cite according to Appel’s revised Annotated Lolita, New York, Vintage Books, 1991 (51, 70, and 94) with a quote from Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Appel’s notes expand on the Byron allusions in Lolita. Chateaubriand is also found with additional discussion (pp. 145 and 210).

Other “suspicious characters” cited in Ada who also appeared earlier in Lolita include Beaudelaire (162,262). We are reminded by Appel in the first of these of Beaudelaire’s “Invitation au Voyage” wherein the author urges, “mon enfant, ma soeur” to “aller la-bas vivre ensemble” (my emphasis). James Joyce is repeatedly invited into Lolita by Nabokov (pp 4, 69, 187, 207, 221, 262 etc.). Therewith we recall Bloom’s suspicious feelings, in Ulysses, towards his daughter that lead Molly to send their daughter away. And we remember that Margaret C. Solomon emphasized in her book Eternal Geomater (Carbondale, etc: Southern Illinois University Press, 1969)that “a major theme of Finnegans Wake, the mutual seduction between an older man and a very young girl, which makes use of numerous historical and legendary relation-ships.” The Wake also pays considerable attention to the incest theme, both father-daughter incest and sibling incest.

Less immediately apparent will be references to Goethe (pp 70. 76, 240, and possibly 262), and we should not forget Goethe ’ s use of the incest theme in connection with that strange little girl Mignon in Wilhelm Meister (cited by Boyd, p. 117). And note an “obvious pun” on the term “Mann act,” and “act” as a euphemism for the “sexual act” (p. 150), if we remember the complex bi-generational incest basis of Thomas Mann’s novel Der Erwaehlte, which presumably Appel did not himself appreciate, but which Boyd points out (p. 120). Nor did Appel seem to understand (or at least he did not mention) the fact that

[39]

Melville’s Pierre is a novel of “incestuous passion” as one critic has labeled it, merely referring to that novel ’ s “gloomy ‘ Byronic ’ themes,” without making it clear which of Byron’s various themes he intends (p. 33). (Boyd cites Melville’s novel and its use of brother-sister incest at the end of his article (Comparative Literature 38, 1986, p 225).

All of these allusions and citations make the very air of Lolita redolent with the incest motif. And we shall close this section of “guilt by association,” by recalIing the overwhelming presence of Poe, with Appel’s extended elucidation (pp. 9,12, 31, and especially 43 note 5), whose incestuous aspects we point out in the third section of this paper — the hints of pedophilia having been often alluded to by others.

“Know your own daughter”

But turning now from these co-conspirators in incest with whom the novel is peppered, we wish to emphasize an even more important aspect of the incest theme in Lolita, namely how insistent the novel and the members of its cast are on the paternal-filial relationship, and thereby on the incestuous nature of sexual congress between Humbert and Lolita. Humbert soon imagines “Father and daughter melting into these woods! ” (my italics) (p. 84). As they check into the Enchanted Hunters he requests a cot “for my little daughter,” and he signs the register, “Dr Edgar H. Humbert and daughter” (p. 118). Soon Lolita is, “my impossible daughter” (p. 131) and Humbert reminds her, “I am your daddum, Lo,” and “I am your father” (p. 150).

Lolita herself is complicit in this identification from her first words to Humbert after his marriage to her mother, when she addresses him on page as “Dad,” and complains a few lines later that, “you haven’t kissed me yet” (p. 112). Soon he is “deah fahther” (p. 220). By the end of the novel she has written him a “Dear Dad,” letter, asking for financial help. And on Humbert’s arrival she introduces him to her husband, saying, “This is my Dad” (p. 273). The result of this introduction is that

[40]

Dick addresses Humbert as, “Mr Haze” (pp. 274, 275), not the first person in the novel to make this error (see pp. 110, 195).

In wreaking revenge on Quilty, Humbert tells him, “You see, I am her father” (296); and, again, “She was my child.” Indeed, already before he had fetched Lolita from camp after her mother’s death, he let the Farlows, neighbors to the Hazes, understand that Lolita was the child of an affair he, Humbert, had with Charlotte in April 1934 (p. 100); so that Jean Farlow tells her husband, “She is his child, not Harold Haze’s ... Humbert is Dolly’s real father” (p. 101).

Humbert’s incestuous intentions are most strikingly, perhaps for someofusmost shockingly, laid whenHumbert contemplates fathering on Lolita a girl child, a subsequent nymphet, and on that second nymphet, he will sire a “Lolita the Third,” on whom he will then practice “the art of being a granddad” (p. 174). Nabokov uses this same notion in Ada wherein “an American, a certain Ivan Ivanov of Yukonsk(!), impregnates his five year old granddaughter...and then five years later also gets [her] daughter with child (p. 134). Here there can be no doubt of the incestuous nature of Humbert’s multi-generational fantasy, and of the frisson he gets from it (see chapter 21 of Ada, and Boyd’s notes to it, especially lines 14-24), nor of its being an openly stated continuation of his relationship with Lolita: an incestuous relationship. Lolita herself was the first to call a spade a spade, with no attempt at circumlocution, when she and Humbert first checked in at the Enchanted Hunters. As Humbert explains to Lolita that as they travel, “we shall be thrown a good deal together. Two people sharing one room inevitably enter into a kind of — how shall I say — a kind ...

‘The word is incest,’ said Lo” (p. 119).

“It’s called incest”

But of course, despite all of the father daughter talk, Lolita is not Humbert’ s biological daughter. Therefore there can be no question of incest Quod erat demonstrandum. Case closed,

[41]

failed syllogism. But wait! There is a flaw in this reasoning, for the presumed syllogism lacks a major premise. This is the premise that should, for example, state a definition for us: a definition whose predicate is then included as a term in the minor premise. Incest is defined in the OED as “The crime of intercourse... between persons related within the degree within which marriage is prohibited.” We want to emphasize first the connection between prohibited sexual acts and prohibited marriage. For of course the latter prohibition follows logically from the first.

Following up on the term “crime,” and being mindful of Humbert’s repeated emphasis on the illegality of his and Lolita’s relationship, we also recall Humbert’s insistence on his familiarity with laws dealing with sexual conduct. Although there are fifty slightly different law codes for fifty different states, they bear a generic similarity, and all clearly relate what is forbidden sexually to what is forbidden maritally. Thus, for example, we learn that the Kentucky Revised Statutes (Charlottesville, VA: The Michie Company, 1990), Volume 17, Section 530.020, states, “Incest. — (1) A person is guilty of incest when he has sexual intercourse with ... an ancestor, descendant, brother or sister. The relationships referred to herein include blood relationships, [but also they include]...relationships of parent and child by adoption, and relationships of stepparent and stepchild.” Now we remember that quite early on Humbert has referred to Lolita as his “legal stepdaughter”(p. 71). Although this prohibition against marital and sexual activity between stepparent and stepchild is not found in all states, it is far from uncommon among legal codes of the various states.

Of course these civil laws typically have their source in religious ones, to which we turn next. Our earliest reference wi 11 be to Old Testament book of Leviticus. There it is clearly stated in 18; 17, “Thou shaft not uncover the nakedness of a woman and her daughter....” (The Annotated Laws of Massachusetts.

[42]

New York: Lawyers Cooperative Publishing, 1994 Chapter 207, phrases its law, “No man shall marry ... his wife’s daughter....”). These prohibitions of sexual relations, and thereby, of course, of marriage, with a stepdaughter, are also stated in major ecclesiastical comments on the subjects, such as the New Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967-1979; see volume 7, p. 419), which likewise refer us to the above cited passage of Leviticus. It also informs us that the various types of incest are prohibited on the basis of their violations of family structure: “[the incest prohibition eliminates sexual competition within the family that otherwise could become dysfunctional by impeding the socialization of the young and tension management for the parents” (p. 420), wisely remarking also that these taboos are not primarily “for eugenic reasons.” (There is an online version that may be consulted under the lemmata “incest” and “consanguinity”). The Church ofEngland has a similar prohibition with respect to stepdaughters.

The New Catholic Encyclopedia in addition calls our attention to an example in the New Testament where St Paul (in I Corinthians 5; 1-12) loudly condemns a man for having sexual relations with his stepmother. That passage may remind us, also, of the Greek story of Phaedra, who attempts to seduce her stepson Hippolytus, thereby providing us with a Phaedra complex to parallel Dr. Freud’s Oedipus complex (if I may to cite him to my current audience!). It is quite clear that the laws of man and the laws of God, as well as ancient literary tradition, do regard sexual activity of a stepparent, like Humbert, with a stepchild, like Lolita, as constituting incest.

Reverting briefly to my previous topic of literary allusions to incestual relations, I would like to call attention to another law in the marriage section of our Kentucky Revised Statutes (still used as an example of laws also found in other states and in other countries). Section 402.010 tells us that “No marriage shall be contracted between persons who are nearer of kin to each other... than second cousins.” That law brings us back to

[43]

Edgar Allan Poe whose father was the brother of Virginia Poe Clemm’s mother, making Virginia and her husband Edgar first cousins (as were Charles Dodgson’s parents, an instance surely known to Nabokov, although “unindited” here by him). Most other states also have such laws that specifically forbid marriage of first cousins. Our helpful New Catholic Encyclopedia also classifies first cousin marriages as incestuous (Volume 4, p. 194), going on to point out that the Eastern Orthodox Church prohibits marriages between third and even fourth cousins, facts that we assume Nabokov was generally familiar with (see Martin Oppenheimer’s Forbidden Relatives: The American Myth of Cousin Marriages, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996). We shall permit Edgar to stay with our earlier crowd of incestual allusions, as well as with the class of pedophiles — at least within the fictional universe of Lolita.

Thus Lolita pairs the twin themes of prohibited sex: pedophilia and incest.

—John A. Rea, Lexington, Kentucky

THE FAIR INVENTION IN NABOKOV’S ADA AND GORKY’S “THE LIFE OF KLIM SAMGIN”

In order to mortally beat one’s enemy, one has to know one’s enemy well.

(Maksim Gorky, Preface to Chateaubriand’s Réne and Constant’s Adolphe)

The word “incest” is for the first time mentioned in Ada even before Van and Ada, brother and sister, become lovers. When, at the picnic on the occasion of Ada’s twelfth birthday, she and Grace Erminin play anagrams (1.13), Grace imprudently suggests “insect:”

[44]

‘Scient,’ said Ada, writing it down.

‘Oh no!’ objected Grace.

‘Oh yes! I’m sure it exists. He is a great scient. Dr Entsic was scient in insects.’

Grace meditated, tapping her puckered brow with the eraser end of the pencil, and came up with:

‘Nicest! ’

‘Incest,’ said Ada instantly.

‘I give up,’ said Grace. ‘We need a dictionary to check your little inventions.’

Insect and incest are thus closely linked in Ada (see also Boyd: “Annotations to Ada” 85.09-17). A subtle connection between those apparently very different notions can be discovered also in Maksim Gorky’s tale “The Life of Klim Samgin (Forty Years)” (1925-1936).

The hero of this longest (1650 pages!), even though it has remained unfinished, povest ’ (“tale”) in the world literature that spans not forty but forty-six (from 1871 to 1917) years is “a young man of mediocre gifts,” whose life served as a major theme for the 19th century writers and who will remain, according to Gorky (see his Preface to Chateaubriand’s Réne and Constant’s Adolphe, 1932), the main hero in the literature of the 20th century. His name is Klim Ivanovich Samgin and he is almost ideally colorless as a character. In fact, he can vie in colorlessness with the Man without Qualities, who in Robert Musil’s eponymous novel (that was written almost simultaneously with Gorky’s tale and even surpasses, despite being incomplete itself, the latter in length) goes into a mystical incestuous relationship with his sister. Like Musil’s hero, Samgin is weder Fisch, noch Fleisch. On the other hand, his rather rare name can be regarded as a product of crossing siomga (Russian for “salmon”) with samka (Russian for “female of an animal”). In that case, Samgin would be just the opposite: a strange mix of fish and flesh. It seems that the author himself could not make

[45]

up his mind what his hero is, and only on the last page, in the notes to the tale’s ending, we find out that Samgin is, or rather was, an insect – a cockroach that a revolutionary soldier or sailor crushes with his boot.