Download PDF of Number 59 (Fall 2007) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 59 Fall 2007

____________________________________

CONTENTS

News 3

by Stephen Jan Parker

Notes and Brief Commentaries 5

by Priscilla Meyer

“A Source of Character Names in Pale Fire” 5

–Matthew Roth

“Ember’s ‘Index by First Lines to a Verse Anthology’ 9

in Bend Sinister”

–Stuart Gillespie

“Krug and Hamlet” 14

–Frances H. Assa

“Through an Open Door” 19

–Gennady Barabtarlo

“Nabokov and Comic Art: Additional Observations 21

and Remarks”

–Gavriel Shapiro

“White Spiders and Robert Frost in Lolita’’' 31

–Rachael Ronning

“The Monkey Ship at Mesker Zoo” 33

–Marianne Cotugno

“Lubitch, Fletow, and Grimm in King, Queen, Knave” 36

–Philippe Villeneuve

‘“Grattez le Tartar...’ or Who Were the Parents 40

of Ada's Kim Beauharnais?”

Part One. by Alexey Sklyarenko

Annotations to Ada 50

28: Part I Chapter 28

by Brian Boyd

2006 Nabokov Bibliography 78

by Stephen Jan Parker and Kelly Knickmeier

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 59, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

- Brian Boyd’s “Annotations to Ada” (because superseded by, updated, hyperlinked and freely available on, his website AdaOnline).

In some but not all cases the downloadable pdf version of the print Nabokovian will have the annual bibliography and the “Annotations to Ada.”

[3]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

Nabokov Society News

Society memberships/subscriptions remain relatively stable. In 2006, the Society had 163 individual members (117 USA, 46 abroad) and 93 institutional members (75 USA, 18 abroad). By early November 2007, there are 151 individual members (110 USA, 41 abroad) and 92 institutional members (74 USA, 18 abroad).

•••••

Odds and Ends

– In Russia, Azbooka press is in the process of publishing the complete works of Nabokov. Already available are:

Mashen’ka – November 28, 2006

Korol’, Dama, Valet – December 27, 2006

Pnin – March 23,2007. A 50th Anniversary edition, in revised translation by Gene Barabtarlo, along with an essay.

Otchayanie – May 10, 2007

Dar – June 13, 2007

Kamera Obskura – June 29, 2007

The next volume to appear shortly is Barabtarlo’s translation of The Real Life of Sebastian Knight.

Also in process, most importantly, is a new Lolita edition, edited by Dmitri Nabokov, that will contain for the first time a significant passage and other details omitted in previous Russian versions which were garbled to varying degrees by inaccuracy and sloppiness.

[4]

Scholars should thus be aware that the Symposium set of publications in Russia is no longer the only one. Symposium texts should thus not to be viewed as the “standard” Russian editions of Nabokov’s works, as some have claimed.

– A most interesting work most recently published by Cornell University Press is Style is Matter. The Moral Art of Vladimir Nabokov, written by Leland de la Durantaye.

*****

I wish to express my greatest appreciation to Ms. Paula Courtney for her essential, on-going assistance, for more than 26 years, in the production of this publication.

[5]

NOTES AND BRIEF COMMENTARIES

By Priscilla Meyer

Submissions, in English, should be forwarded to Priscilla Meyer at pmeyerf@wesleyan.edu. E-mail submission preferred. If using a PC, please send attachments in .doc format; if by fax send to (860) 685-3465; if by mail, to Russian Department, 215 Fisk Hall, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT 06459. Deadlines are April 1 and October 1 respectively for the Spring and Fall issues. Most notes will be sent, anonymously, to at least one reader for review. If accepted for publication, the piece may undergo some slight editorial alterations. References to Nabokov’s English or Englished works should be made either to the first American (or British) edition or to the Vintage collected series. All Russian quotations must be transliterated and translated. Please observe the style (footnotes incorporated within the text, American punctuation, single-spacing, paragraphing, signature—name, place, etc.) used in this section.

A SOURCE OF CHARACTER NAMES IN PALE FIRE

In Pale Fire, Charles Kinbote reveals (reliably or not) that he is the author of “a remarkable book on surnames” (Vintage 267). This is not entirely surprising, given the many glosses of family names that appear throughout the commentary. While Kinbote’s book on surnames is fictional, Nabokov must have gotten his own information on surnames from an actual source. As I will show, Nabokov clearly obtained much of his information on surnames from Sabine Baring-Gould’s Family Names and Their Story (London, Seeley & Co., 1910).

[6]

Shakespeare/Shalksbore

In his note to lines 433-434, Kinbote introduces us to the “Harfar Baron of Shalksbore... whose family name, ‘knave’s farm,’ is the most probable derivation of‘Shakespeare’” (208). According to Baring-Gould, Shakespeare “is derived from Schalkesboer, the knave’s farm. Neither schalk nor knave originally implied anything but what was honorable. Schalk was a servant, and enters into the names Godshalk, God’s servant” (366). Directly below this last sentence, Baring-Gould has placed a footnote to an earlier entry (regarding the Old Norse “hauld”) which reads “Harald Harf. Saga.” These adjacent references likely explain why Nabokov made Shalksbore a “Harfar Baron.”

Lukin

Regarding the maiden name of Shade’s mother, Caroline Lukin, Kinbote says that “Lukin comes from Luke, as also do Locock and Luxon and Lukashevich” (100). Baring-Gould’s entry for “Luke” reads, “whence come Lukis, Lukin, Luxon, Lukitt, Locock” (57). Baring-Gould does not mention, as Kinbote does, that “the Lukins are an old Essex family.” Nabokov may have gotten that connection from a query by Charles Robinson in the April 2, 1859 issue of Notes and Queries, titled “Luckyn or Lukin of Essex.” It reads, in part, “I am endeavouring to complete a full pedigree of this old family, branches of which have been settled for many years at Great Baddow, Roxwell, Messing, and Dunmow” (280).

Fyler

Fleur de Fyler’s name appears to be a simple joke, a “[djefiler of flowers,” as Kinbote puts it (213). Just after this phrase, however, Kinbote asks Fleur if she still plays the viola. In an earlier scene, Fleur sits “trying, as one quietly insane, to mend a broken viola d’amore” (110). Fleur’s instrument of

[7]

choice is explained by Baring-Gould’s entry for the “Vyler,” which reads, “the player on the viols; hence Fyler” (113).

Bretwit

According to Kinbote, Oswin Bretwit’s last name means “Chess Intelligence” (180). In his chapter on “Name Stories,” Baring-Gould tells the story of a Slavonic knight who is a guest at the court of a Spanish moor. He is challenged to a game of chess by the “Moorish Princess,” who tells him that the reward for winning is “[tjo smash the board on the head of the defeated.” The knight wins and smashes the board so hard on the princess’s head that she bleeds and has to wrap a bandage around her head. The knight then returns to his kingdom, “where he assume[s] the name of Bretwitz, or the witty chessboard-player, and the chessboard as his arms, and as his crest the Moorish Princess with bound head” (337). Note that Gradus, Oswin Bretwit’s adversary in the note to line 286, ends up with a bloody scalp after being smashed over the head by Kinbote’s gardener, whom Kinbote would like to attire “according to the old romanticist notion of a Moorish prince” (292).

Campbell/Beauchamp

In the note to line 130, Kinbote’s tutor, Walter Campbell, faces off in a game of chess with his mirror image, Monsieur Beauchamp, both names translating as “beautiful field.” In his chapter “Scottish and Irish Surnames,” Baring-Gould writes, “Campbell is supposed to be De Campobello, or Beauchamp, but this is very doubtful”(377). While Baring-Gould finds the relationship spurious, Nabokov apparently found it too tempting to resist.

Lavender

In his note to line 408, Kinbote introduces Joseph S. Lavender, adding that “the name hails from the laundry, not from the laund”). Nabokov here combines information from

[8]

two of Baring-Gould’s observations, and steals a quip. Baring-Gould writes that “Lavender as a surname does not come from the herb, but signifies a washerman” (96). In a separate note, he writes that “Laund” means “a grassy sward in the forest,” derived from “the O.N. lund, that signifies a sacred grove” (169). Note too that Baring-Gould was also a novelist, and one of his novels, Cheap Jack Zita (1894), briefly mentions a criminal named “Joseph Lavender” (284).

Bodkin

There is no mention in Baring-Gould of either Botkin or Kinbote as a surname. He does, however, include an entry for Bodkin, which Kinbote in the index relates to V. Botkin’s last name. According to Baring-Gould, Bodkin comes from “Baldwin” (54), a personal name which later became a family name (67). He also notes, in his introduction, that “Baldwin de Boilers received from Henry I. the barony of Montgomery and the hand of his niece, Sybilla de Falaise” (14). This is the only mention of any name corresponding to Sybil.

Charles

Baring-Gould gives extensive attention to the name Charles. He relates it back to the Anglo-Saxon “ceorl” or “churl” and notes that in Anglo-Saxon “the churl is almost, if not quite, indistinguishable from the serf,” while in the Edda of Saemund (which Kinbote explicitly mentions) the churl is represented as a “free bonder,” the child of Afi and Amma. Baring-Gould concludes: “Carl signified a man generally. Charles is rarely found as a Christian name in England before the time of Charles I. The surnames Charles, Charley, and Caroll, from the Latin form Carolus, remain with us—the last in the United States” (117).

Given all of these correspondences, it is clear that Nabokov relied heavily on Baring-Gould as he chose the names for Pale

[9]

Fire. Moreoever, Family Names and Their Story is probably as close as we will come to knowing what Kinbote’s own book on surnames may have contained, were it real.

—Matthew Roth, Grantham, Pennsylvania

EMBER’S “INDEX BY FIRST LINES TO A VERSE ANTHOLOGY” IN BEND SINISTER

It regularly happens in examining works of art that an element we at first assume is a product of the imagination, something the artist has dreamed up or concocted, turns out to be directly drawn from readily available sources. This disappoints some critics, while others stress that artistic creativity, unlike the divine variety, is not a matter of ex nihil activity. In this example from Bend Sinister, Nabokov’s source can be conclusively identified, opening a small window onto the author’s workshop.

Not far into Bend Sinister, Ember telephones his old friend Krug, at first hesitating because Krug’s wife is dying in hospital:

Ember hesitated, then dialled fluently. The line was engaged. That sequence of small bar-shaped hoots was like the long vertical row of superimposed I's in an index by first lines to a verse anthology. I am a lake. I am a tongue. I am a spirit. I am fevered. I am not covetous. I am the Dark Cavalier. I am the torch. I arise. I ask. I blow. I bring. I cannot change. I cannot look. I climb the hill. I come. I dream. I envy. I found. I heard. I intended an Ode. I know. I love. I must not grieve, my love. I never. I pant. I remember. I saw thee once. I traveled. I wandered. I will. I will. I will. I will.

(Bend Sinister, New York: Holt 1947, 31)

This passage can, no doubt, be read in different ways – as a depiction of a heightened state of self-awareness, or as a

[10]

miniature satire on the egocentrism of lyric poetry. But however it is viewed, it would occur to few readers that Nabokov was not responsible for the list of poems. Do first-line indices ever look so obsessive, or so repetitious? Could anyone butNabokov have made up a title like “I am the Dark Cavalier”? In fact, however, it can be shown that Nabokov’s source for almost everything in this passage is a specific poetry index dating to 1940.

The narrator’s words “an index by first lines to a verse anthology” imply that any real-life source should be sought among verse anthologies of the period in which Bend Sinister was written (the novel was first published in 1947). This proves slightly misleading, because even the largest anthologies of the era are not large enough to include as many poems as would be needed to generate this number of adjacent index entries beginning with the word “I.” Neither does any of their first-line indices match Nabokov’s selection at all closely. The best match I have found is with An Oxford Anthology of English Poetry, chosen and edited by Howard Foster Lowry and Willard Thorp (NewYork, 1935), which, although l,232 pages in length, contains only twenty-six entries beginning with the word (not the letter) “I,” and amongst them produces matches for only eight of Nabokov’s thirty-four first lines (or rather beginnings of lines). One must turn instead to a work which is not an anthology but an index: Granger's Index to Poetry and Recitations. The relevant edition is the third (Chicago, 1940; the previous one of 1920 was much smaller), which covers 75,000 titles-а different order of magnitude from any anthology’s coverage, and much more than sufficient, as we shall see, to produce everything in Nabokov’s list.

Turning to the first-line index section we find Nabokov’s first title, “I am a lake,” in the following form:

I am a lake, altered by every wind. See Lake, The.—Squire

This refers the reader to Granger’s title index section, and to a poem listed there under the name of the writer Sir J. C. Squire. All items in this first-line index are cross-referenced to the title section in this fashion. Between this item and the point at which Nabokov stopped browsing (i.e. the lines beginning “I

[11]

will”), Granger’s presents no less than seventy-eight columns containing some 4,500 first lines. Nabokov’s list runs to only thirty-four. Nabokov did indeed borrow all or very nearly all his first lines from Granger’s, but he borrowed very selectively. His first item is drawn from the first page of poems beginning “I” (p. 1057, where the section-heading letter “I” appears), and his final items from near the final page of “I” entries (that is, the pronoun rather than the letter – p. 1098). He has, of course, also reduced most of the entries he found from a full line to two or three words.

Once the source is identified, it is possible to show in fuller detail how Nabokov used it. After the Squire poem, he passed over 45 other first lines before coming to:

I am a tongue for beauty. Not a day. See Eagle Sonnets (XIX).—Wood

Perhaps some of the intervening 45 first lines might have served his purpose, and he was allowing his eye to roam freely, but it is easy to see that none of the following, for example, would conform to the rest of Nabokov’s initial sequence, because an adjective precedes the noun:

I am a little boy about so many years old

I am a little country girl

I am a lone, unfathered chick

I am a lonely bachelor

Equally, none of the following syntactically more suitable lines, also drawn from the 45 index items intervening between the first and second items Nabokov selected, would have worked so well, if what he was looking for at this point was a sequence of non-human identities like “lake,” “tongue,” and “spirit”:

I am a pilgrim come from many lands

I am a soldier

I am a stranger in the land

[12]

Further investigation might be done of the selection Nabokov made as he scanned the pages concerned (pp. 1057-96), and why he accepted some openings and rejected others. But this seems to have nothing to do with any feature of the poems concerned other than the first words he found in the columns of Granger’s. His selection was made for the purpose of generating the incantatory verbal construct which appears on page 31 of Bend Sinister, and for this purpose neither the authors, the poems’ content, nor any other aspect of them mattered except their first few words and the effects these words would create as part of the sequence. Indeed, it is often not possible to say which authors or poems are referred to in Nabokov’s list, because there are several, or many, items beginning the same way. For example:

I dream of a languorous, tideless shore. See East Wind—Brown.

I dream of a White Hart that through the meadows. See Hardwick Arras.—Childe

I dream that you are kisses Allah sent. See Rose-Lady. The.—Riley.

Because of the scale of Granger's Index, the same thing applies even on occasions when we might suppose only one possible poem could be available, as with “I saw thee once”:

I saw thee once, and nought discerned. See Discovery, The.—Newman.

I saw thee once - once only - years ago. See To Helen.—Poe.

By my count, only thirteen of the thirty-four openings in the Index belong to only a single poem.

[13]

Even apart from the particular words he assimilates, Nabokov’s effects are partly a reflection of what he found, and not purely of his own invention. Some of the patterns and proportions in the fictional list resemble those of Granger’s Index, in that some constructions are more common than others. Seven of Nabokov’s items (a fifth of the total) begin “I am;” in Granger’s, 7 1/2 of 78 columns are occupied by entries beginning thus. Nabokov also provided multiple entries for “I cannot” (2, as against 72 in Granger) and, climactically, “I will.” In Granger “I will” gets 2 columns, or 114 items; Nabokov’s four-fold “I will” is more than proportionate. On the other hand, Nabokov was not tempted to multiply in some other cases where Granger might have suggested it, such as “I know” (3 columns). Similarly, “I love” appears 120 times in Granger – more times than “I cannot’’ – but figures only once in Nabokov’s list. Hence, while there is no doubting where Nabokov has taken his material from, and while almost nothing in his passage comes from anywhere else-even the layout of Granger’s columns, with its hanging indentation for turned lines (i.e. entries requiring two printed lines) helping to make the “long vertical row of superimposed I’s” stand out-authorial shaping and control are strongly in evidence.

A few other points should be mentioned. With only one exception, Nabokov truncated the first lines he found in Granger’s. No first-line index looks like Bend Sinister’s, because first-line indices contain complete first lines. The only complete first line here is Austen Dobson’s comic opening “I intended an Ode,” which is of course already a very short line. One of only two openings apparently missing from Granger’s, “I blow,” is perhaps merely Nabokov’s adjustment – the better to fit it in his series, which is in the present tense at this point –

From “I blew, I blew, the trumpet loudly sounding.” See Trumpeter, The.—Higginson.

There is just one Nabokovian first line found nowhere at all in Granger’s, the third: “I am a spirit.” This appears one place out of alphabetical sequence in the Bend Sinister list, and an attentive reader might wonder why. The reason is that the list

[14]

is haunted by death. Easily the most evocative of its openings, “I am the Dark Cavalier,” is from a poem by Margaret Widdemer whose subject Nabokov would have inferred from its first line, especially in the line’s complete form as supplied in Granger. This is the first of its three stanzas:

I am the Dark Cavalier; I am the Last Lover:

My arms shall welcome you when other arms are tired;

I stand to wait for you, patient in the darkness,

Offering forgetfulness of all that you desired.

Ember was notably close to the dying woman, scenes from whose life he is soon to recall. And, though he does not know it, by the time he dials Krug’s number, which of course is also her number, she is already dead. She is an otherworldly presence, a spirit, flitting through the plangent music Ember hears in the telephone’s tone.

—Stuart Gillespie, University of Glasgow

KRUG AND HAMLET

In chapter seven of Bend Sinister, Adam Krug, the protagonist, pays a visit to his friend Ember at his apartment. The chapter begins quietly, as an idyll after the violence that has preceded it, but veers suddenly and swiftly to macabre terror, all the while taking signals from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Ember (whose name reminds us that he has been entrusted with the cremation of Olga, Krug’s late wife) is an expert on Shakespeare. In this chapter which immediately follows Krug’s panic and then relief at his son David’s brief disappearance, the two friends reunite for the first time since Olga’s death. They avoid speaking of Olga, in an attempt to enjoy a short respite from reality, choosing instead to discuss a play, a bastardization of

[15]

Hamlet written by a Professor Hamm, that Ember, Literary Advisor to the State Theater, has been asked to direct for the authorities.

Some of the chapter’s allusions to both Shakespeare’s Hamlet and the library scene discussion of it in James Joyce’s Ulysses have been thematically examined by Samuel Schuman, Michael H. Begnal and Lois Feuer, with little exploration of the details by which Nabokov links his work to the others. Indeed, Feuer disdains such inquiry: “The correspondence between Hamlet and Bend Sinister is after all thematic rather than literal, and to go any further, to look for, say, the doubles of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, would be to approximate too closely the ingenious methodology of that cautionary figure for critics, the earnest and oblivious Professor Hamm” (Critique: Studies in Contemporary’ Fiction, 30:1. Fall 1988, 11). On the contrary, such an inquiry is Nabokovian. Nabokov has written: “In art as in science there is no delight without the detail, and it is on details that I have tried to fix the reader’s attention. Let me repeat that unless these are thoroughly understood and remembered, all ‘general ideas’ (so easily acquired, so profitably resold) must necessarily remain but worn passports allowing their bearers short cuts from one area of ignorance to another” (quoted in Boyd, Brian, Vladimir Nabokov, The American Years, 1991,340).

Krug and Ember’s discussion recalls the playfulness of the Scylla and Charybdis library episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses, in which Stephen Daedalus panders to the literary notables of Dublin, spouting his theories about Hamlet as they flutter about him “like an Auk’s egg.” All three protagonists, Krug, Daedalus, and Hamlet, face a crisis of choice—to be or not to be, to sail towards the proverbial Scylla or Charybdis. However, Krug, unlike Stephen, will be unable to make the right choice. Whereas Stephen turns his path away from fossilization (the Auk’s egg) and towards Bloom and a more risky direction in his artistic quest (are-Bloom), Krug’s and Hamlet’s equivocation will lead

[16]

to their extinction. In rotten kingdoms, men of conscience who hesitate and consider cannot survive.

As does Shakespeare, Nabokov lightens the tragic plot with comic interludes. Ember and Krug amuse themselves with the absurd details of Hamm’s authorized version of the play in which Fortinbras, not Hamlet, is the hero. This version, called The Real Plot of Hamlet, is topsy-turvey, but has a logic of its own. Since Hamlet is a pathetic weakling, The Real Plot gives the throne to Fortinbras, a proper heroic type with the right racial features. The fact that, for a protagonist, Fortinbras does not really have much of a part until the end of Shakespeare’s play does not trouble the authorities, since it was the Bard himself who inexplicably marched him onto the stage, in full force, as the Elsinore court is expiring.

According to the laws of heroics, Hamlet does not measure up. What is required is Hamlet in khaki. As Stephen Daedalus says, “Khaki Hamlets don’t hesitate to shoot” (Joyce, James, Ulysses, 1961, 187).

The comic pair of Bachofen and Hustav, sent to arrest Ember, are reminiscent of Gildenstern and Rosencrantz, both in their Germanic names and in their role in the story— they all cheerfully serve as spies for the regime “To keep those many bodies safe/That live and feed upon your majesty” (3.3.10-11) — and neither pair escapes execution.

The name Rosenkrantz amalgamates “rosen,” meaning rose colored or reddish, and “krantz.” A kranz is a coronet, garland, circle, or a ring of mountains. Gildenstern’s name combines “stem,” in English, the back end of anything, with “gild,” meaning to overlay with a thin layer of gold. Thus Shakespeare’s duo can be said to have a red top and a golden bottom, heightening the foolishness of their role. Hustav and Linda Bachofen, are likewise dupes of the regime. Hustav sports a red tulip in his lapel, the crown of which would resemble a ring of peaks, thus recreating Rosenkrantz’s name. His name also brings to mind the German “husten,” to cough, or, as a vulgar idiom, to not give a damn. Bachofen sounds like a comic hybridization of the two great German composers: Bach’s head

[17]

with Beethoven’s bottom. “Hofen” resonates with the German “haufen,” which can mean “the common herd” (easily herded by someone like Paduk) or a pile such as in a toilet. (Nabokov could be as scatological as he was eschatological.)

The gallows humor of Nabokov’s pair is reminiscent of the two clowns in Hamlet's cemetery scene who banter with Hamlet and Horatio while digging what proves to be Ophelia’s grave. Indeed if Krug is Hamlet, Ember is Horatio.

Both Hamlet and Bend Sinister contain an inset play. Ember and Hamlet are in effect engaged in mounting plays on the same subject: the destruction of a legitimate regime by a usurper under the pretext of legitimacy. Hamlet devises his play about the murdered king to assess Claudius’s reaction and thereby smoke out Claudius’s guilt. Ember’s authorized play is a smokescreen that is made to arise from the embers of Shakespeare’s play.

Hamlet, like Krug is a man who values reason above passion.

and blest are those

Whose blood and judgment are so well commingled,

That they are not a pipe for fortune’s finger

To sound what stop she please. Give me that man

That is not passion’s slave, and I will wear him

In my heart’s core, ay, in my heart of heart

(3.2.68-73).

Krug rationalizes and hesitates until his hesitation proves fatal to himself and David. Bend Sinister and Professor Hamm’s play remind us that the rulers of authoritarian regimes must conquer and rule with an iron fist to insure the continuation of the regime. They must never suffer defeat. Intellectuals like Hamlet or Krug will not be tolerated by such a regime unless pressed into its service.

Hamlet has the power that comes with being a favorite of the people: “He’s loved of the distracted multitude/Who like not in their judgment, but their eyes” (4.3.4-5).

[18]

Hamlet loses this advantage by failing to act promptly, allowing Claudius to plot his ruin. Similarly, Krug, because he is loved at home and respected abroad, gains only temporary protection from the inevitable death sentence—and fails to use the delay to his and his son’s advantage.

Both stories end with an explosion of violence against an evil regime. In Shakespeare’s play the murderous king is killed by the dying Hamlet, and most of the court is now dead, except for Horatio who has been asked to live to tell Hamlet’s story. In Bend Sinister, Krug fails in his last-ditch attempt to kill Paduk, and he and all his friends, including his Horatio, Ember, are murdered. Only “Nabokov” himself–or rather “the anthropomorphic deity impersonated” by him—remains to tell the story, having placed himself in a position to observe Krug’s “nether world” in the light reflected by a puddle beneath his window. (Cf Stephen Daedalus’s comment: “So in the future, the sister of the past, I may see myself as I sit here now but by reflections from that which then I shall be”) (Ulysses, 194). In this way Nabokov reminds us that the history of Krug is after all just a story, just as Shakespeare’s players would have emerged from behind the scenes to take their bows. But Krug’s story is not about an old kingdom in a far-away land; it is about events similar to those that occurred not long ago in the heart of Europe.

Both plays measure society by how its most vulnerable innocents fare. In Hamlet, the innocent Ophelia is made to suffer; in Sinisterbad, the lamb to be sacrificed is David. We are spared the full description of David’s horrible fate: instead, we are graphically told how children are tortured in general without having to watch as David is thrown into the pit. Even this hearsay is painful, but the pain it is not gratuitous. In our real world, David’s fate was the fate of more than a million children at the hands of the Nazis. Innocence and fragility are doomed in the face of evil. At least Krug, mercifully struck mad, can be convinced that death is “but a question of style.”

[19]

My sincere thanks to Leona Toker for all her generous advice and to Priscilla Meyer for her encouragement.

—Frances H. Assa, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

THROUGH AN OPEN DOOR

Pushkin’s “The Queen of Spades” is an elaborate literary joke, as are his previous attempts at fiction. It is derived from La Motte Fouqué’s rendition of a Swedish non-thriller (La Dame Pique, 1825) and Ducange’s Trente ans, ou la vie d’un joueur (1828). This is not the place to discuss Pushkin’s prose, even if VN mentions the tale’s origin in passing in his EO commentaries (for an elaboration see “Pushkin’s Pikovaia dama, Gene Barabtarlo and Vera Nabokov, in Russian Literary TriQuarterly 24, 43-62,1990). I merely wish to counter a few points in Mr. Karpukhin's note, “What Troubled Chekhalinsky?,” The Nabokovian 57, Fall 2006, 14-17).

Mr. Karpukhin thinks that Chekalinski had known the three cards and blanched at at the prospect of facing its fateful sequence. This can hardly be Pushkin’s design.

The very nature of the game —a card version of a rouge ou noire—makes it impossible to keep any winning sequence a secret. Whatever series of three cards was imparted to the Countess by Saint-Germain, it was not the trey the seven the ace, or every gambler would try the combination immediately after. In other words, the mysteriously winning combination must be custom-made in each case. That Hermann hopes to use it in Paris implies that he—already quite mad—hopes that the news of his three cards will travel more slowerly than he. Indeed after the magazine publication, Pushkin makes a rollicking remark in his diary: “My Queen of Spades is much in vogue. In Moscow gamblers place their stakes on the 3-7-Ace sequence” And this is precisely what they did in Hermann’s

[20]

fictional world once the news of the fabulous win spread after the first occurrence of the series, with the same result as in real Moscow. It is, then, certain that Hermann receives his personalized combination, previewed at the earlier stages of his rapidly advancing madness (“that is what will increase my fortune threefold, sevenfold’’).

Further, Chekalinski is not a millionaire, at least not in the common sense of the word: he is said to have won and lost millions, and therefore swings, like all gamblers, indeed like Pushkin, between short term riches and long term debts. He is “visibly perturbed” simply because his bank is a potluck affair (skladchina), and by winning that much, Hermann would have broken it (376,000 roubles would now buy two dozen Scuderia Ferraris).

Chekalinski is just old enough to be an illegitimate fruit of the Countess’s first affair involving the fateful cards; at her funeral, Hermann was rumored, half-seriously, to be her Illegitimate son (but cf. his broodings as he is leaving the Countess’s house by the backstairs). In the scene at the card table Pushkin, tongue-in-cheek, may have set up a rencontre between the late Countess’s two bastards: “This all looked like a duel”. Hence the slight embarrassment (smushchenie), both here and in her boudoir episode).

Chelakinski’s behaviour is not really strange. What is strange in this tale (and strange that Nabokov did not point it out) is that Hermann enters the Countess’s house through the locked doors (‘Shveitsar zaper dveri' [The doorman locked the doors])—an important bit of information that Lizaveta Ivanovna-—who could have simply given Hermann the keys to the backdoor— omitted; and he enters a brightly lit hall, even though in a previous paragraph we learn that “the house went dark.”

Of course, the Countess’s ghost pays him a return visit in a politely symmetrical way: the ghost also enters through a locked door (rather then, say, a wall).

[21]

Again, the entire thing is a complex and somewhat self-conscious literary jest — not without serious implications and wistful musings, of course. But if one misses the light part, one will never understand why Baratynski, on hearing Pushkin read to him his Belkin Tales, was in stitches.

—Gennady Barabtarlo, Columbia, MO

NABOKOV AND COMIC ART: ADDITIONAL OBSERVATIONS AND REMARKS

Nabokov demonstrates his great fascination with comic art throughout his entire life—a tendency that has been duly noted in Nabokov scholarship. (See, for example, Gavriel Shapiro, “Nabokov and Comic Art,” Nabokov at the Limits, ed. Lisa Zunshine, 213-34 [New York & London: Garland, 1999]; Clarence F. Brown, “Krazy, Ignatz, and Vladimir: Vladimir Nabokov and the Comic Strip,” Nabokov at Cornell, ed. Gavriel Shapiro, 251-63 [Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 2003].) In the following pages, I would like to offer some additional observations and remarks on this subject.

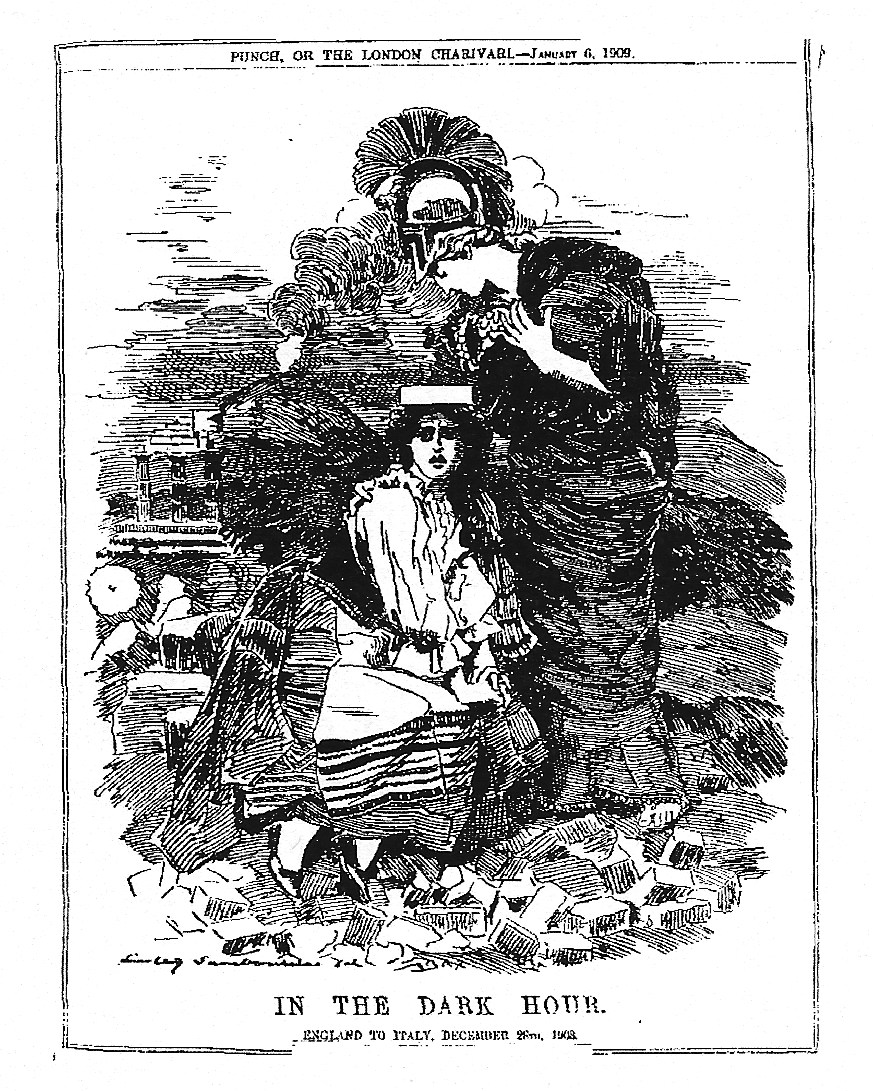

In Speak, Memory, Nabokov recalls that “Historically and artistically the year [1909] had started with a political cartoon in Punch: goddess England bending over goddess Italy, on whose head one of Messina’s bricks has landed—probably, the worst picture any earthquake has ever inspired” (SM 142; italics are Nabokov’s). Indeed, the January 6th issue of Punch for 1909 includes a cartoon by the English caricaturist, illustrator, and chief cartoonist оf Punch at the time—Linley E. Sambourne (1844-1910). The cartoon depicts a horror-stricken Lady Italy, surrounded by bricks and stones, with one brick “resting” on her head, and Lady England expressing her condolences by reclining her head and pressing one arm to her bosom while placing

[22]

another on Lady Italy’s shoulder; in the background, there is an erupting volcano.

It is remarkable that Nabokov not only accurately describes the cartoon which he saw many decades earlier as a nine-year-old boy, but also remembers his judgment of the bad taste with which the artist handled one of the most gruesome natural disasters of the twentieth century—the Messina earthquake of 28 December 1908—that took the lives of nearly 200.000 people. By dubbing it “the worst picture,” Nabokov obviously alludes to the cartoon’s poor artistic merit: indeed, the brick on Lady Italy’s head looks too symbolic and, without any shading, hardly resembles a brick but rather poorly fitted headwear. Furthermore, the cartoon, it must be added, is factually inaccurate, as Mt. Etna, to which the artist is apparently alluding in the background, was not active at the time of the earthquake and

[23]

therefore could not directly contribute to the disaster. Curiously, Nabokov mentions this earthquake in Pnin: it was “the world-famous Egyptologist Samuel Schonberg who perished in the Messina earthquake” (Pnin 94).

Comic art as a pictorial form undoubtedly fascinated Nabokov who until his early youth aspired to become a painter. As we may recall, Nabokov studied drawing with several artists, specifically with Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, who, among other things, was fond of caricature and not infrequently practiced it himself (see M. V. Dobuzhinsky, Vospominaniia [Moscow: “Nauka,” 1987], between 224 and 225). Apparently under Dobuzhinsky ’ s influence, Nabokov tried his own hand at caricature when drawing “the carp-shaped outline of the fat-sided body” (“karpoobraznoe ochertanie bokastogo tela”) of his tutor “Lenski,” who dubbed this attempt of young Nabokov a “despicable caricature” (“otvratitel'naia karikatura”) (Ssoch, 5: 250). Another target of the young Nabokov was “Mademoiselle,” his French governess. His talent as a cartoonist is expressed in the following description: “Apart from the lips, one of her chins, the smallest but true one, was the only mobile detail of her Buddha-like bulk. The black-rimmed pince-nez reflected eternity. Occasionally a fly would settle on her stern forehead and its three wrinkles would instantly leap up all together like three runners over three hurdles” (SM 105-6). The comparison of wrinkles to runners leaping over hurdles is very graphic and superbly caricaturesque. Nabokov would eventually convey these cartoon-like observations to drawing paper: “The face I so often tried to depict in my sketchbook, for its impassive and simple symmetry offered far greater temptation to my stealthy pencil than the bowl of flowers or the decoy duck on the table before me, which I was supposedly drawing” (SM 106). Mademoiselle’s face was apparently not the only goal of the young artist. This becomes evident in The Defense, which Nabokov endowed with some details from his own childhood, specifically, as he put it, “I gave Luzhin my French governess”

[24]

(Def 11). Nabokov describes how Luzhin the boy “slitted his eyes and rived his drawing pencil with an eraser, as he tried to portray her protuberant bust as horribly as possible” and how “the governess stretched toward the open drawing book, toward the unbelievable caricature” [Def 16, 17).

The fascination with comic art accompanied Nabokov throughout his entire creative life and found its expression in his novels as well as in short prose. We come across examples of distinguished cartoonists’ names and their work mentioned already during the writer’s “Russian years.” Thus, in King, Queen, Knave, Nabokov names two fleeting characters, Max and Moritz, “Two young men from the store [who] could hardly hide their giggles” (KQK 218), after the characters of the famous comic strip. This comic strip, with the two urchin-pranksters, Max and Moritz, dates from 1864 and was developed by the famed German cartoonist Wilhelm Busch (1832-1908). Nabokov’s father’s library contained eight books by Busch, including one titled Max und Moritz. (See Sistematicheskii katalog biblioteki Vladimira Dmitrievicha Nabokova. Pervoe prodolzhenie [1911], 21). Further, the narrator of the story “A Busy Man” (1931) points out that the protagonist’s pen name, Grafitski, reminds “one of the ‘Caran d’Ache’ adopted by an immortal cartoonist” (Stories 286). Caran d’Ache was the nom de plume of a distinguished Russian-born French cartoonist Emmanuel Poiré (1859-1909). (Nabokov would have been undoubtedly less enthusiastic about Caran d’Ache had he known that the artist had been the author of anti-Semitic cartoons; see Eduard Fuchs, Die Juden in der Karikatur [Munich: Albert Langen, 1921], 235-37.) And in the story “Vasiliy Shishkov” (1939), there is a mention of “ill-fitting suits that the émigré cartoonist Mad gives to his characters” (Stories 498). MAD was the acronymic nom de plume of the Odessa-born artist Mikhail Aleksandrovich Drizo (1887-1953). (About MAD, see Vera Terekhina, “’Besposhchadnaia umnitsa’— karikaturist MAD,” in Evrei v kul'ture russkogo Zarubezh'ia 4 [1995]: 220-28. For numerous cartoons by MAD, see S. A.

[25]

Aleksandrov, comp., Satira i iumor russkoi emigratsii [Moscow: “Airo—XX,” 1998].)

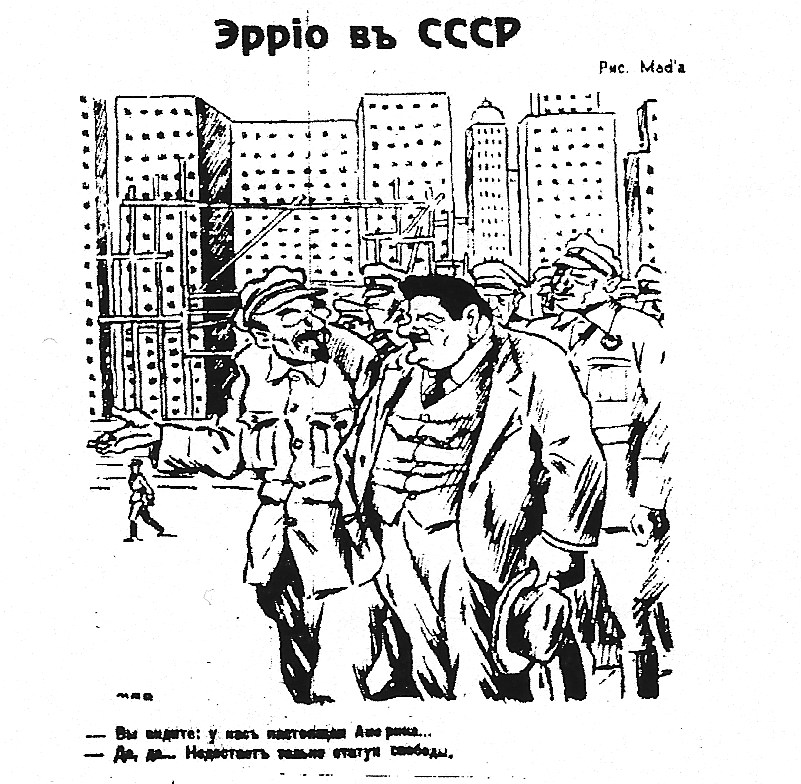

Nabokov alludes to a cartoon by MAD in The Gift when mentioning “Herriot (whose macrocephalic initial in Russian, the reverse E, had become so autonomous in the columns of Vasiliev’s Gazeta as to threaten a complete rift with the original Frenchman)” (Gift 36). The following 1933 MAD cartoon, entitled Herriot in the USSR, shows the French politician accompanied by a Soviet guide. The caption, that reflects the exchange between them, reads: “—You see: we have a real America... —Yeah, yeah... Only the Statue of Liberty is missing” (Fig. 2). The association is suggested by the caricatured portrayal of Herriot, whose head and face, shown in profile, indeed resemble «]», the Russian reverse ‘E.’

Throughout his literary legacy, Nabokov not only demonstrates his close familiarity with and great understanding of comic art, but also creates his own verbal imagery, most likely inspired by it. Nabokov, who lived in Germany for fifteen years (1922-37), was no doubt particularly fascinated with the cartoons of the Munich-based weekly Simplicissim us. Nabokov mentions this periodical in at least two of his works—once in Dar (see

[26]

Ssoch, 4:510; in the novel’s English translation [ 1963], Nabokov substituted Simplicissimus, which ceased to exist in 1944, for Punch, its English equivalent, more familiar to his English-speaking readers at the time; see Gift 335), set in Berlin, and again in Bend Sinister, for which Nazi Germany looms as the obvious prototype of a totalitarian state. (For a mention of the periodical spelled Simplicissimus, see BS 15.)

In all likelihood, Nabokov was familiar with Simplicissimus, and specifically with the artistic craftsmanship of Thomas Theodor Heine (1867-1948), an outstanding German cartoonist, from his St. Petersburg years. We may recall that the World of Art journal frequently reproduced graphic works from Simplicissimus, and the World of Art painters, such as Dobuzhinsky, were very fond of the German periodical and the skill of its artists, especially Heine. Thus Dobuzhinsky writes: “I admired /.../ T. Th. Heine and other graphic artists in Simplicissimus; in general this periodical was the sharpest and most advanced at the time, and I impatiently awaited the appearance of its every issue” (Dobuzhinsky, Vospominaniia, 157).

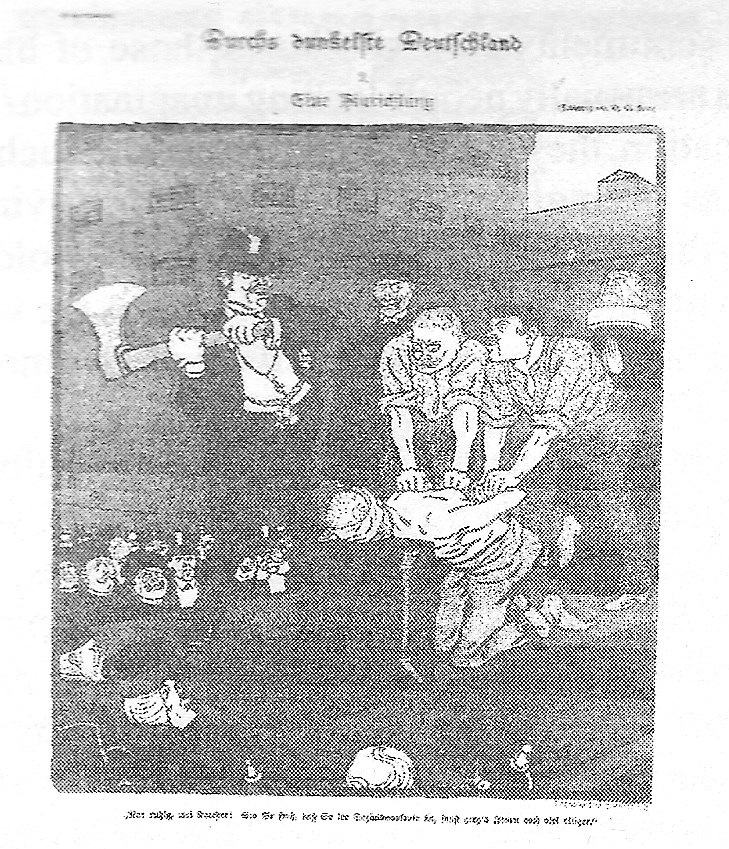

We find an excellent example of visual imagery, seemingly inspired by this celebrated magazine, in Invitation to a Beheading, which, by Nabokov’s own admission, “deals with the incarceration of a rebel in a picture-postcard fortress by the buffoons and bullies of a Communazist state” (CE 217). It is quite possible that the novel’s execution scene was influenced by one of Heine’s Simplicissimus cartoons on the subject. Just as in that cartoon, Cincinnatus is sentenced to a beheading with an ax by the dressed-up executioner, initially assisted by the two henchmen, with the crowd enjoying “the show” and with the prison fortress looming in the background.

[27]

(In this cartoon that dates from 1899—Nabokov’s birth year— , the title and the subtitle read: “Through darkest Germany. An Execution” [“Durchs dunkelste Deutschland. Eine Hinrichtung”]. The caption reads: “Just calm down, my good man! Be glad that you are not a social democrat; otherwise, you would have been much worse off’ [“Nur righig, mei Kutester! Sin Se froh, dass Se kee Sozialdemokrate sin, sonst ging’s Ihnen noch viel ekliger”]) (I am indebted for this translation to Leslie Adelson, Cornell Professor of German Studies.) We may recall that M’sieur Pierre also tells Cincinnatus at the execution block, “There must be no tension at all. Perfectly at ease” (IB 222).

This cartoon is evidently also alluded to in King, Queen, Knave, in the episode of Dreyer’s visiting the crime exhibition at the police museum. Here Dreyer, apparently reflecting his creator’s thoughts, muses about the boredom and “the banality of crime” (KQK 207): “And then the final Bore: at dawn, breakfastless, pale, top-hatted city fathers driving to the execution. /.../ The condemned man is led into a prison yard. The executioner’s assistants plead with him to behave decently, and not to struggle. Ah, here’s the axe” (ibid.). This supposition seems to be accurate, since in his Cornell lectures Nabokov

[28]

expressed sentiments very similar to those of his character: “Criminals are usually people lacking imagination/..../Lacking real imagination, they content themselves with such half-witted banalities as seeing themselves gloriously driving into Los Angeles in that swell stolen car with that swell golden girl who had helped to butcher its owner /.../ Crime is the very triumph of triteness, and the more successful it is, the more idiotic it looks” (LL 376).

As I have mentioned elsewhere, the light-bulb monogram comprised of the protagonist ’ s and his antipode’s Cyrillic double initials, О О and A A, “artfully planted in the grass, in branches, on cliffs” (IB 189), forms a swastika (see Shapiro, Delicate Markers, 36-49). An emergence of this ominous sign as part of the landscape might be suggested to Nabokov by yet another Simplicissimus cartoon by Heine that depicts swastika-shaped flowers growing in a meadow (see Shapiro, Delicate Markers, 39).

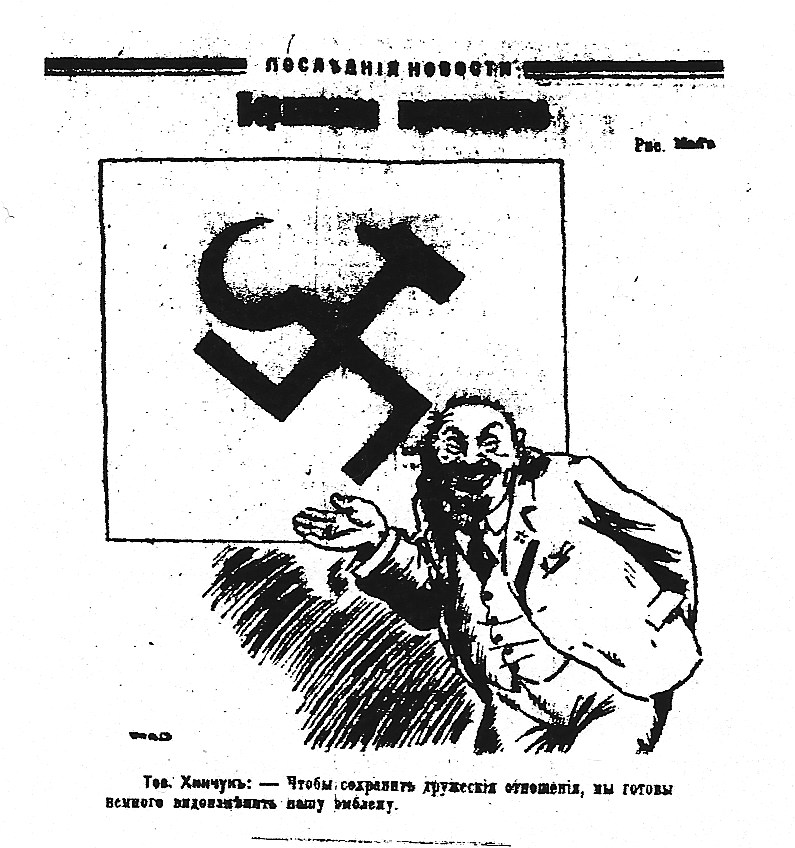

The bulb monogram episode commands our attention in another important respect. While the Cyrillic double initials of the protagonist and of his antipode suggest a swastika, the symbol of Nazi Germany in whose capital, Berlin, Nabokov had resided while composing the novel, the Roman double initials, C. C. and P. P., suggest the hammer-and-sickle—the symbol of the Soviet Union—that other police state, into which Nabokov’s native Russia had turned (see Shapiro, Delicate Markers, 49-55). This, of course, points to the interconnection and interchangeability of the two totalitarian systems and, furthermore, to the universal nature of totalitarianism as presented in this manifestly dystopian novel. Here, Nabokov was perhaps inspired by the following 1933 cartoon by MAD that graphically conveys the interchangeability of the Soviet and Nazi tyrannies.

[29]

The caption, which reflects Adolf Hitler’s rise to power [he was named German Chancellor on 30 January 1933], reads: “Comrade Khinchuk: —In order to preserve amicable relations we are prepared to modify our emblem a little” (Lev Mikhailovich Khinchuk [1868-ca.l939] was the Soviet ambassador to Germany [1930-34]. Khinchuk (spelled Hinchuk) is mentioned in The Gift; see Gift 159.)

Invitation to a Beheading is of great interest for an additional reason, since in this novel Nabokov created a distinct verbal comic strip of his own. Thus, Emmie, apparently egged on by M’sieur Pierre, draws “a set of pictures, forming (as it had seemed to Cincinnatus yesterday) a coherent narrative, a promise, a sample of fantasy” (IB 61-62). Clarence F. Brown, a literary scholar and professional cartoonist, has masterfully transformed this verbal comic strip into a pictorial one (see his “Krazy, Ignatz, and Vladimir: Nabokov and the Comic Strip,” 261). This comic strip is designed to torment Cincinnatus by falsely raising his hopes that, in accordance with his “romantic” dreams, he will be liberated by Emmie, the prison director’s daughter, much like the brigand-prisoner, who outlines to his paramour, the jailer’s daughter, a plan for their joint escape in Lermontov’s poem “The Neighbor” (1840). (For a more detailed

[30]

discussion on the subject, see Shapiro, Delicate Markers, 140-41.)

It is noteworthy that in Bend Sinister Nabokov also creates a comic strip of his own:

In those days a blatantly bourgeois paper happened to be publishing a cartoon sequence depicting the home life of Mr. and Mrs. Etermon (Everyman). With conventional humor and sympathy bordering upon the obscene, Mr. Etermon and the little woman were followed from parlor to kitchen and from garden to garret through all the mentionable stages of their daily existence, which, despite the presence of cozy armchairs and all sorts of electric thingumbobs and one thing-in-itself (a car), did not differ essentially from the life of a Neanderthal couple. (BS 77)

As Alfred Appel, Jr. has perceptively suggested, in creating this strip, Nabokov drew upon the example of Blondie, and “Etermon’s attire recalls Mutt (as opposed to Jeff), Andy Gump, or Jiggs in Bringing Up Father.” (The former was the brainchild of Murat Bernard “Chick” Young [1901-73], and the latter, of George McManus [1884-1954].) Appel has also noticed that the poster pictures of the smoking Mr. Etermon anticipate the ads that depict Quilty puffing Dromes cigarettes (see Alfred Appel, Jr., Nabokov’s Dark Cinema [New York: Oxford University Press, 1974], 76).

In conclusion, Nabokov displayed a distinct propensity for comic art throughout his life. An outstanding verbal artist, he employed in his works comic art descriptions, real and imaginary. Nabokov’s fascination with comic art, that markedly modem and manifestly popular form of the pictorial, provides a deeper insight into the writer’s poetics. It demonstrates that Nabokov customarily strove, in the words of The Gift protagonist, for his “way along this narrow ridge between [his] own truth and a caricature of it” (Gift 200), that is, he sought to strike a balance between seriousness and playfulness, between the dramatic and the comedic, thereby demonstrating that the cosmic and the

[31]

comic can relate not only paronomastically (cf., for example, Gift 244, NG 143, and SO 58), but also function together in the universe of Nabokov’s fiction.

—Gavriel Shapiro, Ithaca, New York

WHITE SPIDERS AND ROBERT FROST IN LOLITA

In Vladimir Nabokov’s LOLITA, the narrator Humbert Humbert aspires to immortality through language. He places himself with great authors, referring to himself as Edgar H. Humbert (75). Humbert not only dons Edgar Allan Poe’s name but borrows work from another poet as well. After an adult Lolita declines Humbert’s request to come away with him, he mimics the last line of Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” when he replies, “It would have made all the difference” (280).

Abraham P. Socher and Anna Morlan have examined Nabokov’s relationship to Frost and his poetry in Nabokov’s works and both address Frost’s poem “Design” as an important reference in PALE FIRE. “Design,” with its moths and metaphysics, is relevant to Nabokov’s thematics. Nabokov believed that the “coincidence of pattern is one of the wonders of nature” (STRONG OPINIONS 157). Frost’s poem is concerned with design in nature. The poem places a white spider atop a white flower and this coincidence of color lures an unsuspecting white moth to its demise:

I found a dimpled spider, fat and white.

On a white heal-all, holding up a moth.

In the foreword to LOLITA John Ray Jr. PhD gives two titles for Humbert’s memoir; “Lolita or The Confession of a White Widowed Male”(3). The second title is often read as a comic example of similar titillating titles and then is swept away

[32]

like a musty accumulation, but it may be a subtly woven snare. Humbert Humbert, the “author” of the confession, twice describes himself as a spider. The first time, he is describing the web he has woven throughout the Haze home in search of Lolita: “I am like one of those inflated pale spiders you see in old gardens,” pale since he is wearing white pajamas (49). The confession’s title here becomes a pun on the black widow spider, as Humbert is a white widow(er) even before marrying the mother of Lolita. But this unusual white widow spider may have a literary precedent. Humbert the “pale spider” points out the lilac “design” on his white pajamas and, like the spider in Frost’s poem, is also indebted to the uncanny pattern of fate (complete with diagram) when the timely death of Lolita’s mother grants him the sole guardianship of his twelve year old nymphet.

“Humbert the wounded spider” (as he later calls himself) comes closest to successfully “fixing the nymphet” when describing Lolita’s tennis form (54). The tennis scene works like a snapshot suspending Lolita in “a vital web of balance” (231). This web has aesthetically captured his prey. Humbert the white widow spider professes that he has given poor Lolita immortality through his art, but he has also ensnared her in a “design of darkness,” as Frost’s poem suggests:

What but design of darkness to appall?

If design govern in a thing so small.

When Humbert meets Lolita as a married woman, “her pale-freckled cheeks were hollowed, and her bare shins and arms had lost all their tan.” (49,269) His “warm-colored prey” has been sucked of life (49). The immortality through art that Humbert grants his nymphet is only the “dead leaf’ preservation of a spider’s shrouded prey for the adult Lolita (277).

—Rachel Ronning, St. Paul, MN

THE MONKEY SHIP AT MESKER ZOO

I am in the process of visiting sites across the United States mentioned as destinations or potential destinations for Humbert and Lolita during their cross-country trips. The present use of one site should raise an eyebrow or perhaps a chuckle from readers of Lolita. Described as “A zoo in Indiana where a large troop of monkeys lived on a concrete replica of Christopher Columbus’ flagship” (Library of America edition 158), Alfred Appel Jr. identifies the site in his annotations to the novel, and explains that he became aware of the place through his students at Indiana University.

The Mesker Zoo’s beginnings are described in an article by Gilmore M. Haynie, who designed many of the zoo ’ s enclosures. Haynie writes that “We are living today in a highly competitive age,” and sees Mesker Zoo as Evansville’s means of attracting the regional tourist dollar that had become increasingly scarce (“Value and Problems of Zoological Parks in Smaller Cities.” Parks and Recreation. Vol XIV. No. 3, 1930, 135). A strong supporter of the zoo in those days was Karl Kae Knecht, who became a nationally prominent cartoonist with the Evansville Courier, his cartoons helped raise awareness of the zoo to a broader population. A cartoon in the August 7, 1933 edition of the Evansville Courier by Knecht portrays a group of visitors crowded around the monkey ship while the “crew” dives into the moat, climbs the masts, and swings from the rigging; two men in the foreground speak: “We come several times a week;” “A pipe and a rockin’ chair an’ I could watch ‘em all day.”

Although readers of the novel may think the zoo is best known for its connection to Lolita, the story that dominated headlines was that of Kay, the elephant, who was purchased in part with money collected by the children of Evansville through an effort spearheaded by Knecht. Knecht’s cartoons frequently featured Kay. Kay’s life is documented in detail through the newspapers, from her arrival to a parade that caused schools to

[34]

close, to her sad departure after causing the death of her favorite handler, Bob McGraw, in 1954

The “monkey ship,” as locals call it, was designed by Haynie, who pioneered barless enclosures for the zoo beginning with a bear pit, then creating the monkey ship and subsequently a lion pit. To complete this enclosure, Haynie took advantage of the labor made available through the Works Progress Administration. Haynie wrote about his efforts in “A New Type of Monkey Island,” for the trade journal, Parks and Recreation (October 1933). The new type of enclosure eliminates zoo directors’ concerns about earlier, less aesthetically appealing enclosures with catwalks and wires that presented problems for staff cleaning and access. The ship featured a heater to keep the living quarters warm for its residents in colder months, and Haynie boasts that “[t]he three ship’s masts are also fully equipped with rigging, lookouts, shrouds and rat-lines which offer plausible and inviting means for getting the animals into the air where their play may be better observed” (“A New Type of Monkey Island” 59-60). Haynie explains that he chose the “Santa Maria” as a model to “add a historical background and thus secure an additional educational interest” (Ibid. 58).

The first residents, more than a dozen rhesus monkeys, officially boarded the ship on July 13, 1933. In the early twentieth century, rhesus monkeys were probably the most common monkey in zoo exhibits and elsewhere; as William M. Mann points out, the rhesus were “the animals that spell monkey to the average person. They are imported into the United States in lots of hundreds, or even thousands, and retailed at small prices as pets, show animals, or for use in medical laboratories” (Wild Animals In and Out of the Zoo. New York, New York: The Series Publishers, Inc, 1949 45).The Evansville Courier on July 14, 1933 included an article describing how the new crew behaved and noting that one of the monkeys feigned drowning just to tease an attendant on hand (“Monkeys Board ‘Santa Maria,’ Feign Drowning to Keep Attendant Busy”). From that time, the monkey ship became one of the most popular attractions at Mesker Zoo and

[35]

was home to several troops of monkeys for decades. An undated advertisement beckons, “On the Monkey Ship you’ll meet up with a comical crew of bickering, chattering little Macaque monkeys from India. It’s a hardy bunch of old salts that man that ship, Mate!”

Although concrete structures like the monkey ship had fallen out of favor with zoo directors because they were not safe for residents or guests, the ship at Mesker Zoo remained a popular attraction. In 1986, the monkey ship received a makeover. A former Evansville resident, Michael Kennedy, who was then an artist for Disney World in Orlando, FL, suggested a new color scheme. By May the work was completed by members of the Evansville North Civitan Club, and when work was completed, six squirrel monkeys took up residence (“’Blah’ is out as zoo’s monkeys get colorful home.” The Evansville Courier). Eventually, in 1989 the monkeys were removed from the structure, because zoo officials felt it was an unsafe environment for the inhabitants. In 1995, there was significant discussion of the ship being converted to an amphitheatre, but nothing came of those ideas. Since the monkeys left the ship, people continue to ask where the monkeys have gone. Dr. Diana Barber, Curator of Education at Mesker Zoo, says that residents’ and visitors’ strong memories of seeing monkeys on the monkey ship are part of the reason the site still exists.

Mesker Zoo is well aware of its association with Nabokov’s novel. An article in The Evansville Press in 1995 entitled, “Mesker’s monkey ship rates mention as bit of American originality in ‘Lolita’” discusses the allusion in the novel and asserts:

It doesn’t appear to be an overly flattering reference. The protagonist, who elsewhere in the book derides superficiality in 1950’s America, sandwiches the monkey ship between a visit to a ‘Bearded Lady’ and a scene of “billions of dead fish-smelling May flies in every window of every eating place all along a dreary sandy shore.”

[36]

The article writer quotes Brian Boyd, who suggests that Nabokov may have come across the place while on one of his cross-country butterfly collecting trips.

And what of the monkey ship now? If monkeys no longer live there, is the monkey ship an abandoned concrete structure? Readers of Nabokov’s novel may be surprised to learn that the ship now serves as a bumper boat pool for children. Standing at the top of the hill leading to the attraction, one has to be reminded of Humbert on top of a hill above a playground and regretting that Lolita’s voice is missing from the chorus of children’s voices below.

—Marianne Cotugno, Middletown, OH

LUBITSCH, FLOTOW AND GRIMM IN KING, QUEEN KNAVE

Both Alfred Appel Jr. in Nabokov’s Dark Cinema (1974) and Barbara Wyllie in Nabokov at the Movies (2003) have discussed cinematic procedures and allusions found in Nabokov’s fiction, and a number of other critics have demonstrated how prominently movies figure in his work. Yet one film alluded to in King, Queen, Knave (KQK) has not as far as I know been mentioned by anyone. In Nabokov’s novel, there is a reference

[37]

to two fictitious films, both starring the fictitious actor Hess: The Hindu Student (50) and The Prince (61). According to Jeff Edmunds in “Look at Valdemar! (A Beautified Corpse Revived)”, the former refers to two actual movies: “The Hindu Student—a nonexistent film which is probably a conflation of Das indische Grabmal [The Hindu Tomb, 1921] and Der Student von Prag [The Student from Prague, 1913 and 1926]” (Nabokov Studies, 2, 1995, p. 163). The films, however, more likely allude to Ernst Lubitsch’s The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (1927), which was playing in theatres the same year Nabokov started working on KQK

In Lubitsch’s film, a Prince is sent to Heidelberg in order to study incognito, and manages to fall in love with a young barmaid named Kathi. But family matters back home require him to abandon Kathi and resume his royal duties. Franz and Martha both see this movie on separate occasions, yet they muddle elements of the plot when recollecting it. Arriving home from the cinema, Martha reminds Dreyer of The Prince: “Oh you remember, the student at Heidelberg disguised as a Hindu Prince” (62). Oddly, when Franz sees the movie, the incognito is taken up by the actress, not the actor: “an actress with a little black heart for lips and with eyelashes like the spokes of an umbrella was impersonating a rich heiress impersonating a poor office girl” (92-93). Later both Franz and Martha incorporate elements of the film’s plot in their amorous parlance:

“Let’s pretend you are a Heidelberg Student. How nice you

would look in a cerevis.”

“And you are a princess incognito?” (111).

An incognito princess in Lubitsch’s film would be superfluous because Kathi is not of royal origin.. However, Nabokov developed a habit of conflating multiple allusions in one image in his later works, and it is not a stretch to suppose he began doing so as early as 1927. Julian W. Connolly (Nabokov’s Early Fiction [1992]) suggests that Franz recalls the folktale of

[38]

the frog transformed into a princess once kissed (56), a folktale ultimately inverted by Martha’s transformation into a toad. Yet another work containing the precise plot Franz imagines is found in Friedrich von Flotow’s opera Martha, in which Queen Ann’s maid of honor, Lady Flarriet, adopts the pseudonym Martha in order to attend incognito the Richmond Country Fair. Since Nabokov abhorred the opera as an art form in general, Flotow’s opera more probably caught the eye of Nabokov via Joyce’s Ulysses, in which it appears as a leitmotif providing an ironic counterpoint to Bloom’s unconsummated adulterous liaison with Martha Clifford. Nabokov might have made use of this acquired significance of the name Martha when deciding to name the heroine of his novel after Bloom’s epistolary paramour.

Martha Dreyer is an anagram of “Read rare myth.” The reader who follows such advice discovers an intriguing series of connections. For example, in James Steven Stallybrass’ translation of Jacob Grimm’s encyclopedia of Teutonic mythology (1976), we encounter a king of dwarfs named Goldemar who “would allow himself to be felt, but never to be seen” (509), much like the enigmatic playwright of KQK the play within the novel, also named Goldemar. The playwright is mentioned twice (216 and 224), but never materializes as a character. Or does he? Admonitory writing on the wall appears in KQK when Franz’s landlord Enricht is revealed to be the famous conjuror “Menetek-El-Pharsin” (99), this name evoking the writing on the palace walls during Belshazzar’s feast in the Biblical narrative. Grimm relates an anecdote in which the walls of Goldemar the dwarf-king also display admonitory writing, in fact writing strikingly similar in content to Daniel ’ s interpretation of mene-mene-tekel-parsin: “over his chamber-door it was found written, that from that time the house would be as unlucky as it had been prosperous till then” (510). Goldemar the dwarf-king thus allows an association between two elusive characters in KQK.

This novel, so often dismissed as early and derivative, is a much more carefully wrought work of art than critics have supposed. In light of the allusions just noted and their resonance

[39]

in the novel itself, KQK's importance in the Nabokov canon should be reconsidered. After all, these are just some of the many elements that have been overlooked by past criticism. One notes, for example, that in Lubitsch’s film, Prince Karl Heinrich is the homonymous doppelganger of Heinrich von Hildenbrand, painter of the portrait Martha places next to her grandfather’s daguerreotype (36), as well as Franz’s mysterious landlord, whose wife with a “gray head with something white pinned to its crown” (120) might be none other that Martha herself, “a beautiful lady wearing a black hat with a little diamond swallow" (170).

—Philippe Villeneuve, Ottawa

[40]

GRATTEZ LE TARTARE...” OR WHO WERE THE PARENTS OF ADA’S ЮМ BEAUHARNAIS? PART ONE

by Alexey Sklyarenko

We can grasp everything – both the sharp Gallic wit,

And the dark German genius. Blok

“Unity,” an oracle of our century has said,

“can only be welded by iron and blood.”

Well, we’ll try welding it with love.

Let’s see which lasts the longer. Tyutchev

You may say whatever you want, but a few big drops of

Tamerlane’s blood did settle in our Parisian. Vyazemsky

The famous words “Scratch a Russian and you will find a Tartar” are usually attributed to Napoleon. It is believed that he said them on the Island of St. Helena, where he was held captive by the British. Napoleon’s words were often quoted in the course of the next two centuries: among others, by Karl Marx (who in a letter to Ludwig Kugelmann of November 29, 1869, mentions them and suggests that if a Prussian is to be scratched, a Russian will be found), by Fyodor Dostoevsky (who quotes them verbatim, without mentioning Napoleon, in the epilogue to his novel The Adolescent, 1875) and by Prince P. A. Vyazemsky (who in his Characteristic Notes and Reminiscences of Count Rostopchin, 1877, paraphrases them as follows: “grattez le Russe, vous trouverez le Parisien' and “grattez le Parisien, vous trouverez le Russe, grattez encore, vous retrouverez le Tartare"). Bismarck, when in 1870 he was preparing to attack France, said: “Scratch a Frenchman and you will find a Turk” (see, for instance, André Tardieu’s “The Truth about the Treaty,” 1921). It seems to me, however, that Bismarck was wrong: scratching a Frenchman will reveal not a Turk, but a

[41]

Prussian - moreover, Bismarck himself! But how could that be? And whom will we find if we scratch a Tartar (which was never attempted - at least, not before Nabokov)? To answer these questions we must turn to Antiterran history.

Nations on Antiterra, the planet on which Ada is set, are distributed differently than they are in our world. The whole territory of Earth’s Russia, “from Kurland to the Kuriles,” on Antiterra is occupied by Tartary, while ‘ Russia’ is on that planet “a quaint synonym of Estoty, the American province extending from the Arctic no longer vicious circle to the United States proper” (1.3). The Antiterran France lost its independence in 1815, when it was annexed by England (1.40). We do not know what happened to Napoleon after this annexation and whether he existed on Antiterra at all. His name is never mentioned in Ada - unlike that of his first wife, who is known on Demonia (Antiterra’s other name) as Queen (sic!) Josephine.

Marina Durmanova, the mother of Van Veen, Ada's protagonist and narrator, whom Van believes to be his aunt, drops the name of Napoleon’s wife (and then that of Dostoevsky) during her very first conversation with Van at Ardis (1.5):

Price, the mournful old footman who brought the cream for the strawberries, resembled Van’s teacher of history, ‘Jeejee’ Jones.

‘He resembles my teacher of history,’ said Van when the man had gone.

‘I used to love history,’ said Marina, ‘I loved to identify myself with famous women. There is a ladybird on your plate, Ivan. Especially, with famous beauties - Lincoln’s second wife or Queen Josephine.’

‘Yes, I’ve noticed - it’s beautifully done. We’ve got a similar set at home.’

‘Slivok (some cream)? I hope you speak Russian?’ Marina asked Van as she poured him a cup of tea.

‘Neokhotno no sovershenno svobodno (reluctantly but quite fluently), replied Van, slegka ulybnuvshis’ (with a slight smile). Y es, lots of cream and three lumps of sugar. ’

[42]

‘Ada and I share your extravagant tastes. Dostoevsky liked it with raspberry syrup.’

‘Pah,’ uttered Ada.

I brought up a part of this conversation of mother with her children in my article “Traditions of a Russian Family in Ada’ (The Nabokovian, #52), in which I argue that Marina mentions Dostoevsky not without a secret purpose. She can not very well tell the fourteen-year-old Van that she, and not her late sister Aqua, is his real mother and wants him to guess her secret by himself. She hopes that Van has read The Adolescent that begins with its young hero’s reunion with his parents and younger sister whom he almost never saw in his childhood. Having arrived in St. Petersburg, Arkady Dolgoruky meets his father Versilov for the second time in his life and his sister Lisa, for the first. Similarly, this is only the second meeting of Van with his mother and the first, with his two-year-younger sister Ada (whom Van believes to be his first cousin). After Ada (who apparently didn’t approve of her mother’s mention of Dostoevsky) expressed her disgust at raspberry syrup, or Dostoevsky, or both, Van shifts his glance to Marina’s portrait hanging above her on the wall:

Marina’s portrait, a rather good oil by Tresham, hanging above her on the wall, showed her wearing the picture hat she had used for the rehearsal of a Hunting Scene ten years ago, romantically brimmed, with a rainbow wing and a great drooping plume of black-banded silver; and Van, as he recalled the cage in the park and his mother [Aqua!] somewhere in the cage of her own, experienced an odd sense of mystery as if commentators of his destiny had gone into a huddle. Marina’s face was now made up to imitate her former looks, but fashions had changed, her cotton dress was a rustic print, her auburn locks were bleached and no longer tumbled down her temples, and nothing in her attire or adornments echoed the dash of her riding crop in the picture and the tegular pattern of her

[43]

brilliant plumage which Tresham had rendered with an

ornithologist’s skill.

Before we look closer at this portrait, let us turn to a parallel scene in The Adolescent (Part Three, chapter 7, I), in which Versilov and his son admire the photographic portrait of Arkady ’ s mother made of her when she was young and beautiful. Speaking of the difference between a portrait painted by an artist and a photograph, Versilov mentions Napoleon and Bismarck: “photographs only very seldom resemble the original, and there is a reason for it: every one of us only very seldom looks like himself. Only in rare moments does a human face express its main feature, its most characteristic thought. An artist studies the face and guesses this main thought of the face, even if at the moment when he makes a copy it is not there. As to a photograph, it takes a person unawares and it is quite possible that, at some moment, Napoleon would look silly and Bismarck, tender.” (Actually, the former possibility is unlikelier than the latter, because Napoleon died many years before the invention of photography.)

Van, as he considers Marina’s portrait, doesn’t yet know that his arrival in Ardis was stealthily photographed by Kim Beauhamais, a kitchen boy and a photo fiend at Ardis, the future blackmailer! He will see this and other snapshots that show him making love to Ada in the summer of 1884 only eight years later, when Ada brings him the album bought out from Kim. When he sees it, Van gets furious - not only because Kim dared to spy on him and blackmail Ada, but also because with his photos Kim vulgarized his and Ada’s mind-pictures. It seems to Van that Kim grossly distorted their past, and it is then that the idea to “redeem our childhood by making a book of it: Ardis, a family chronicle” first enters his mind (2.7).

This idea is realized by Van only many years later, when, in the last decade of his life, he writes his memoirs: Ada, or Ardor: a Family Chronicle – to be published posthumously (Van and Ada die in 1967). From Van’s book we learn something of practically every young French-speaking member

[44]

of the Ardis household. The handmaid Blanche is a niece of a cook (1.19), Van’s valet Bout is the butler Bouteillan’s bastard (1.20). Only Kim’s origin and “historical” surname remain a complete mystery. Who were his parents? Is he related in any way to Napoleon’s first wife (or, may be, to Bonaparte himself)? It seems to me that the answers to those apparently insolvable questions must be looked for in The Adolescent.

In the beginning of this novel (Part One, chapter 2, III), Arkady tells the old Prince Sokolsky, who loves to talk about women, of his first erotic experience. He begins his story, in which he for the first time mentions Lambert, his schoolmate at a Moscow boarding-school and a future blackmailer, as follows: “You’d be delighted if I visited some local Joséphine and then came back and report you in detail how I made out. Well, there’s no need for that. I saw a woman completely naked when I was thirteen, female nakedness in all its entirety, and since then I felt quite disgusted.” Arkady proceeds to tell the Prince how Lambert, having stolen from his mother five hundred rubles, visited him at a grammar school, how they at first bought a riding crop, a shotgun and a canary-bird and then went out of town where, in a grove, Lambert tied the canary to a branch with a piece of thread and shot it from an inch or so away (the poor bird “smashed to hundred little feathers”), and how they finally rented a room in a tavern, ordered champagne and had a whore come to them. Arkady, who was three years younger than Lambert, apparently did not participate in the orgy, merely watching it. He intervened only when Lambert began to whip the girl with the riding crop. By grabbing Lambert’s hair, Arkady managed to throw him onto the floor, but Lambert prodded Arkady in the thigh with a fork. When people came in to his cry of pain, Arkady managed to escape from the room and the tavern.

I would like now to suggest that Ada's Kim Beauharnais is the son of a “local Josephine” by Arkady Dolgoruky, the hero of The Adolescent. Despite his loathing of women (or, maybe, because of it), he will eventually visit her and make her pregnant. It will happen already after Arkady completes the

[45]

epilogue to his “memoirs” in May of 1875, beyond the story narrated by him. When we leave him at the end of the novel, Arkady is still a virgin and passionately in love with a rich young woman, the only daughter and heir of Prince Sokolsky (of whose death we learn in the epilogue). The epilogue to The Adolescent seems to hint at the possibility of a happy ending: Katerina Akhmakov, nee Princess Sokolsky, will return from Europe where she travels in the company of her friends and Arkady will marry her as soon as he comes of age. But Nabokov famously loathed happy endings. So he probably had a different continuation in mind: Katerina Akhmakov will fall in love with a foreigner (say, with a French Viscount) whom she will meet during her trip (say, in Paris), and the frustrated Arkady, if he survives the loss, will goto a French harlot and lose his virginity to her. A child bom of that consummation will be stolen by gypsies, smuggled somehow to Antiterra (a twin planet and a contiguous world of the Dostoevskian Terra) and abandoned at Ardis, where it will be raised by servants. We can speculate that the boy receives his “historical” surname, “Beauharnais,” in honor of his mother, who was “a Josephine.” (His first name must have been Akim, but on Antiterra lost its initial. The boy’s truncated name links him to the hero of Kipling’s novel Kim, 1901, but also hints at Kim Philby, the notorious Soviet spy who, on the brink of exposure, escaped to Moscow in the middle of the nineteen sixties.) Of course, this is only my hypothesis, and, I admit, a rather bold one; but, as I’ll presently show, it is not completely unlikely.

But first it is necessary to express several considerations of a “theoretical” order. My version of Kim’s appearance at Ardis doesn’t contradict the approach to literary material Nabokov used in the creation of his own fictional worlds. Just as he borrowed the whole planet from Dostoevsky (from the short story The Dream of the Ridiculous Man; see my article “Ada as a Triple Dream” in The Nabokovian #52), Nabokov borrowed a character - a not yet bom (in fact, not even conceived) son of the protagonist in The Adolescent. This borrowing will be better understood, if we consider Nabokov’s

[46]

views on the good reader. According to Nabokov, a good reader is a thinking person, who identifies him/herself with the book’s author, rather than with its characters, and who enters with the author into a complex relationship. Such a reader can, and sometimes even should, imagine what will happen to this or that character after the book’s last page is turned, to think the characters out of the book, so to speak. Interestingly, Nabokov was not the first writer whose thought followed Dostoevsky’s characters beyond one of his novels. In his article “The Art of Thinking” (included in “The Second Book of Reflections,” 1909), Innokentiy Annensky attempts to guess what in a score of years will become of the characters of Crime and Punishment. But, while Annensky is doing this in order to illustrate the author’s thought, Nabokov enters into a hidden polemic with Dostoevsky by inventing the sequel to The Adolescent that most probably differs from the one its author might have envisioned.

According to the fictitious Editor of Ada, when the book comes out all persons mentioned by name in it are dead. Therefore, we cannot follow with our mind’s eye the future of Ada's characters and have to investigate their past. Of all the characters in Ada, Kim Beauharnais has the most mysterious past. We first see Kim, or rather his silhouette, in the night of the Burning Bam (1.19). He is in the last group of three people whom Van and Ada notice from the library window just before their first lovemaking: