Download PDF of Number 64 (Spring 2010) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 64 Spring 2010

_____________________________________

CONTENTS

News 3

by Stephen Jan Parker

A Brief Note on Japanese Nabokov Scholarship 5

from 2000 to 2010

by Shun’ichiro Akikusa

Notes and Brief Commentaries 13

by Priscilla Meyer

“The Gift and Pushkin’s ‘Queen of Spades’” 13

– Rachel Stauffer

“Conjuring Winter in the Summer” 18

– Jansy Berndt de Souza Mello

“Painterly Connotations in The Original of Laura” 23

– Gavriel Shapiro

“Cynthia’s Broken Series: The Hereafter’s 30

Text and Paratext in ‘The Vane Sisters’”

– Juan Martinez

“Gradus in the Pale Fire Index” 37

– Alex Roy

“Notes on a Famous First Line (‘Light of My Life”)” 39

– Stephen Blackwell

Annotations to Ada 31: Part I Chapter 31 45

by Brian Boyd

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 64, except for:

- Brian Boyd’s “Annotations to Ada” (because superseded by, updated, hyperlinked and freely available on, his website AdaOnline).

In some but not all cases the downloadable pdf version of the print Nabokovian will have the annual bibliography and the “Annotations to Ada.”

[3]

by Stephen Jan Parker

Nabokov Society News

Thus far in 2010, the Society has 125 individual members (88 USA, 37 abroad) and 87 institutional members (74 USA, 13 abroad). This is a bit larger number than last year at this time, when it was 113 individual members and 88 institutional members. If the financial situation improves worldwide, perhaps the membership will increase. At this time the continuing existence of the Vladimir Nabokov Society and The Nabokovian is due largely to the magnanimous, substantial donation given to the Society by Dmitri Nabokov, to whom we are indebted and most grateful.

Income from society membership/subscription and purchases of The Nabokovian past issues in 2009 was $5,802; expenses were $6,232. Thanks to the generosity of its continuing members, in 2009 the Society forwarded $325 to The Pennsylvania State University for support of the Zembla website.

*****

Odds & Ends

– The annual MLA Nabokov Society sessions this year – to be held in Los Angeles, 6-9 January - will be (1) “Nabokov and Translation,” chaired by Stanislav Shvabrin; (2) “Nabokov, Cinema, and Adaptation,” chaired by Christopher Link; and (3) “Nabokov Under Revision,” chaired by Ellen Pifer.

[4]

– Publication of The Original of Laura has been largely well received by reviewers and sales have been excellent in the countries where the work has thus far appeared. For example, it has been the #1 bestseller in Russia. Dmitri Nabokov noted that people waited in line until, in two days, the entire 50,000 initial print ran was sold out, and then an additional 50,000 copies were quickly put out. The sales of the French edition were carefully timed for release on April 22, VN’s birthday.

– 'The University Poem' and Other Poems by Vladimir Nabokov, translated by Dmitri Nabokov, will be published in fall 2010.

*****

I wish once again to express my greatest appreciation to Ms. Paula Courtney for her essential on-going assistance in the production of this publication.

[5]

A BRIEF NOTE ON JAPANESE NABOKOV SCHOLARSHIP FROM 2000 TO 2010

by Shun’ichiro Akikusa

Since 1999, the centennial of Nabokov’s birth, the Nabokov Society of Japan has been operating for the promotion of dialogue and intellectual exchange not only between English and Russian scholars in Japan but also between the Japanese and international scholarly communities. Some Nabokov scholars—Vladimir E. Alexandrov, Brian Boyd, Julian W. Connolly, Alexander Dolinin and Zoran Kuzmanovich—have visited Japan as guest speakers at the convention of the Nabokov Society of Japan. This March, the cherry-blossoming city of Kyoto hosted the fifth international Nabokov conference, rounding off a fruitful decade for Nabokov scholarship.

Now, some Japanese Nabokovians have become more and more active in academic circles outside of Japan; they have been attending international conferences where they present in English and Russian, and one can glean a part of their expertise in several English- and Russian-language journals. Yet this is all, alas, but a tip of the iceberg. Jeff Edmunds, a linguistic genius, who has translated some classics of the Japanese Nabokov School into English and published them on the Zembla website, notes: “Japanese Nabokov scholars arc doing some marvelous work, but the vast majority of Western scholars are not aware of it” {Interview: The News Letter of The University Libraries of the Pennsylvania State University, 1 (2), 2007, 4). In fact, one counts over 150 items on the Nabokov Society of Japan’s website published by the members between 2001 and 2005 (http://vnjapan.org/main/conferences/publications3.html). I hope this modest commentary will help acquaint Anglophone

[6]

readers with some terra incognita in Nabokov studies.

Translation

In Japan, translation is an integral part of academic scholarship. Within the last decade, of course, some important translations have been provided for the Japanese reading public. In particular, it is noteworthy that The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov was translated in 2000-2001 as a result of the first collaborative effort between English- and Russian-literature specialists. In the following year, 2002, Nabokov’s last untranslated novel Transparent Things was translated by Akiko Nakata and Tadashi Wakashima. Thanks to their effort, Japanese readers can now read nearly all Nabokov’s novels and stories, though many of his poems and all of his plays are still unavailable in Japanese. Even a translation of the latest addition to Nabokov’s bibliography, The Original of Laura—Nabokov’s wild card—is now in progress by Tadashi Wakashima. In addition to his creative works, Vladimir Nabokov: Selected Letters and Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya: The Nabokov-Wilson Letters were translated in 2000 and 2004.

On the other hand, there is also a stream of new translations of classic literature. In 2005, Wakashima published the first new translation of Lolita in 30 years. When this acclaimed rendering was to be issued in paperback with annotations, the Nobel Laureate in Literature Kenzaburo Oe—an enthusiastic admirer of Nabokov—wrote the introduction for it. In the spring of 2010, a new translation of The Gift was published as one volume of the World Literature Anthology. The translator, President of the Japan Association for the Study of Russian Language and Literature, Mitsuyoshi Numano, seems to have relied quite heavily on the Russian version of the text. He copiously annotated this new edition.

Additionally, a number of literary journals have featured Nabokov. One of the authoritative English-studies journals, Eigo Seinen [The Rising Generation], devoted an issue to the 50th

[7]

anniversary of the American Lolita in 2008. It features various articles, such as Tadashi Wakashima’s “Koushimado saihou: Rorita to chesu” [Revisiting the Latticed Window: Lolita and Chess] and Akiko Nakata’s “Rorita to simaitatchi” [Lolita and Her Sisters], More recently, one of the most important literary magazines, Gunzo, prepared a special feature on Nabokov and published the translation of “Natasha” by Mitsuyoshi Numano in 2009. This issue also includes a translation of Brian Boyd’s informative essay “Nabokov’s Literary Legacy”— the story of a young scholar’s quest for Nabokov’s Holy Grail—specially written for Japanese readers. Brian Boyd has been well-known in Japan since the appearance of the translation of his biography, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, by Yuichi Isahaya, though The American Years has not yet been translated. The aforementioned examples illustrate a widespread interest in Nabokov among Japanese readers.

Monographs

The first Japanese monograph on Nabokov was published under the title Nabokohu mangekyou [Nabokov’s Kaleidoscope] (Hagashobou, 2001) by Yoshiyuki Fujikawa, the first president of the Nabokov Society of Japan. The book traces the Japanese reception of Nabokov as an atheist in the 1970’s and 80’s. The author, a man of erudition and retentive memory, cites such diverse writers as Swift, Wordsworth, Pater, Joyce, Proust and Dostoevsky, comparing their artistic methods and styles at will. This work contributed a great deal to common perception of Nabokov in Japan.

In 2008, Tadashi Wakashima published a monograph on Lolita—Rorita, rorita, rorita [Lolita, Lolita, Lolita] (Sakuhinsya)-—as the companion piece to his new translation of Nabokov’s text. Though the author downplays his own work as “the guidebook,” it leads not only lay readers but specialists through the wonderland of Lolita. Wakashima, known not only as a prominent Americanist but also as a first-rate composer and

[8]

International Solving Master of chess problems, begins the book with an analysis of Nabokov’s own chess problems. He then shows through a particularly close reading of part 1 chapter 10 his profound knowledge of American mass culture (e.g. the advertisement for the perfume Taboo), following this up with a detailed comparison between the novel and the screenplay. In my opinion, the gem of this book is his idea concerning Nabokov’s crafty use of free indirect speech. Fortunately, we can easily access a part of this multilayered work online as Jeff Edmunds’ English translation: “Double Exposure: On the Vertigo of Translating Lolita” (http://www.libraries.psu.edu/ nabokov/wakashima.htm). Wakashima has also written many suggestive articles on Nabokov, including “Denshi tekisuto to Rorita” [The Electric Text and Lolita] in his book Ranshi dokusya no shinbouken [The Adventures of the Astigmatic Reader], (Kenkyusya, 2004), and he has exerted an enormous influence on younger Nabokovians in Japan.

Dissertations

Slavist Kumi Mouri’s dissertation: Kyoukai wo mitsumeru me: Nabokohu no rosiago sakuhin wo megutte [The Eye Gazing the Border: On VladimirNabokov’s Russian Works], submitted to the University of Tokyo in 2005, was the first doctoral thesis on Nabokov in Japan. It mainly focuses on visual aspects (e.g. photography, cinema and drama) in Nabokov’s Russian works. The uniqueness of Mouri’s study is that she reevaluates these features in the context of the Russian exile’s visual culture, a topic which her distinguished paper “Egakareta ‘daiyon no kabe’: Nabokohu no gikyoku ‘jiken’” [Depicting the “Fourth Wall”: On Nabokov’s Play “The Event”] (Rosiago rosiabungaku kenkyuu, 32, 2000, 151-165) also examines.

In the same year, Americanist Tomono Higuchi submitted her dissertation: Vurajimiru Nabokofu bungaku no tenki: Boumei no kiseki to sakkazou no hensen [Nabokov’s Turning Points: The Years in Exile and the Changing Image as a Writer]

[9]

to Hiroshima University. She divides Nabokov’s creative life into four periods—Russian, Russian exile, and multilingual writer in America and Switzerland—and makes the case for three “turning points” in such works as “Details of a Sunset,” “Spring in Fialta,” The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, Lolita and Pnin. Her published work includes the following essay: “Lolita niokeru “Amerika”: hutarino boumei sakka Vladimir Nabokov to Humbert Humbert” [The “America” in Lolita'. The Two Exiled Writers, Vladimir Nabokov and Humbert Humbert] (Hiroshima Studies in English Language and Literature, 48, 43-53, 2003).

In 2007, the Americanist Maya Medlock (nee Minao) completed her doctoral degree in English from Kyoto University with the dissertation: Reading Nabokov’s Framed Landscape. She adapts a kind of thematologic approach mainly in The Gift and gives a full account of Nabokov’s usage of such motifs as the window, bench, and mail. Making her way through the motif of “entrance and exit,” she concludes an essay by outlining Nabokov’s imaginary topography in the novel. One can glean the essence of her studies in such English papers as “In Search of a Mailbox—Letters in The Gift” (Nabokov Online Journal, 1, 2007) and “Entrance and Exit in Nabokov’s The Gift” (The Albion, 53, 109-139, 2007).

I would also humbly add that Shun’ichiro Akikusa, the author of the present commentary, obtained a doctorate from the University of Tokyo in 2009. The title of his dissertation is Yakusu nowa watashi: Urajimiru Nabokofu niokeru jisaku hon ’yaku no shosou [Translation is Mine: Aspects of Vladimir Nabokov’s Self-Translations], It focuses on Nabokov’s practice of self-translation and consists of some previously published papers, including “The Vanished Cane and the Revised Trick: A Solution for Nabokov’s ‘Lips to Lips’” {Nabokov Studies, 10,99-120,2006) and “Without Racemosa: Nabokov’s Eugene Onegin as an Achievement in His American Years” (Studies in English Literature, 50, 2009, 101-122).

[10]

Other Landmarks

It seems that about 15 Japanese scholars are actively studying Nabokov at present. Though I had to omit them in the introduction for want of space, I would like to mention some of these remarkable scholars here.

Isahaya Yuichi is not only the first Slavist-Nabokovian in Japan but also a specialist of the first wave of Russian exiles. His writing is known for being meticulously bolstered by his his curriculum vitae is expansive, here I would like to cite just two informative papers, “Nabokohu to praha” [Nabokov and Prague] (Gengo bunka, 4 (4), 683-702, 2002) and “Toshi no mitorizu: Nabokohu no berurin” [The Sketch of the City: Nabokov’s Berlin] (Gengo bunka, 6 (4), 553-571, 2004). In these works, he reconstructs Nabokov’s Prague and Berlin of the 1920’s and 1930’s using minute details from the novels and many other materials. Isahaya uploads his recent essays onto his homepage

(http://www.kinet-tv.ne.jp/~yisahaya/), and one can read an English-language translation, compliments of Jeff Edmunds, on the Zembla site: “Lights and Darkness in Nabokov’s Glory” (http://www.libraries.psu.edu/nabokov/isahaya.htm).

Akiko Nakata is probably the most well-known Japanese Nabokov scholar among readers of The Nabokovian. Her main concern is his work in the later English period, especially Transparent Things. She has not only written articles on this work (e.g. “Some Subtexts Hidden in Nabokov’s Transparent Things,” Ivy Never Sere, ed. Mutsumu Takikawa, et al., Tokyo: Otowashobou Tsummishoten, 2009,215-230) but also annotated this novel, and it is likely that the Japanese annotation on her website is the most detailed in any language at present (http://www10.plala.or.jp/transparentt/toumei1.html). She recently published the article “A Failed Reader Redeemed: ‘Spring in Fialta’ and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight” in Nabokov Studies (11, 2007/2008,101 -125). Edmunds also translated her

[11]

paper “Repetition and Ambiguity: Reconsidering Mary" for Zembla (http://www.libraries.psu.edu/nabokov/nakata1.htm).

One might also add that English-literature specialists Shoko Miura and Akira Suzuki and Slavists Masataka Konishi and Kazunao Sugimoto have actively researched various aspects of Nabokov’s life and art.

The Nabokov Society of Japan issued its bulletin Krug from 1999 to 2007 twice a year. Since 2008, Krug has been an annually-published academic journal. It has featured its members’ articles, reviews, notes and bibliography, as well as guest lectures. A recent issue includes the manuscripts of the English lectures, Vladimir E. Alexandrov’s “Plurality of Interpretation and Nabokov’s Lolita" (1, 14-26, 2008), Brian Boyd’s “Verses and Versions” (1,27-40,2008) and Nakata’s review of Leland de la Durantaye’s Style is Matter: The Moral Art of Vladimir Nabokov (2, 65-68, 2009).

Additionally, the 21 st century Center of Excellence Program promoted by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology held a research group on “Aspects of Translation” at Kyoto University from 2002 to 2007. The group consisted of Nabokov scholars not only from Kyoto but from every region of Japan. They have compiled their commentaries on Nabokov’s translation of and commentary on Eugene Onegin in the volume Nabokofu Yakuchu Evugenii Onegin Chukai [Essays and Commentary on Vladimir Nabokov’s Translation of and Commentary on Eugene Onegin] (Kyoto Daigaku Daigakuin Bungakukenkyuka, 2007) which includes not only the members’ commentaries and essays but also Julian Connolly’s English paper “Nabokov, Pushkin, and Eugene Onegin” as a guest contribution.

Last but not least, I would like to mention the consistent activity of the Kyoto Reading Circle’s annotations to Ada. Since 1997, they have been closely reading Nabokov’s most complex novel, Ada, and offering the fruit of their labor to the public. This commentary precedes Boyd’s and proceeds to part

[12]

1 chapter 36 at the time of this writing (end of March 2010). It is available on their website (http://vnjapan.org/main/ada/index.html).

Of course, all the aforementioned materials are just a part of the Japanese scholarship that has been produced and that somewhat secretly continues to increase in size. Japanese scholarship does not seem to belong either to the Western or to the Russian School of Nabokov. Absorbing the erudition of each, we have not been perfectly assimilated into their academic contexts, but rather developed our own unique, “foreign” perspective. Such a position, one hopes, is worthy of Nabokov studies, since Nabokov himself spent most of his life as a foreigner.

[13]

NOTES AND BRIEF COMMENTARIES

By Priscilla Meyer

Submissions, in English, should be forwarded to Priscilla Meyer at pmeyer@wesleyan.edu. E-mail submission preferred. If using a PC, please send attachments in .doc format; if by fax send to (860) 685-3465; if by mail, to Russian Department, 215 Fisk Hall, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT 06459. All contributors must be current members of the Nabokov Society. Deadlines are April 1 and October 1 respectively for the Spring and Fall issues. Notes may be sent, anonymously, to a reader for review. If accepted for publication, the piece may undergo some slight editorial alterations. References to Nabokov’s English or Englished works should be made either to the first American (or British) edition or to the Vintage collected series. All Russian quotations must be transliterated and translated. Please observe the style (footnotes incorporated within the text, American punctuation, single space after periods, signature: name, place, etc.) used in this section.

THE GIFT AND PUSHKIN’S QUEEN OF SPADES

Alexander Pushkin’s Pikovaia dama (1834) (Queen of Spades) (QS) is similar to The Gift in its inclusion of puzzles, codes, and plays on language. In QS this is most often analyzed in the context of Pushkin’s use of numerical values in the magical combination revealed to Hermann by the Countess: the three, the seven, and the ace. Caryl Emerson has suggested that “the codes we get in [Pikovaia dama] ... were designed by Pushkin, not to build any single unified structure, not to solve any single puzzle...Pushkin provides us, not with a code, and not with chaos, but precisely with the fragments of codes, codes that tantalize, but do not quite add up” (Caryl Emerson. “’The Queen of Spades’ and the Open End,” Pushkin Today.

[14]

Ed. David Bethea. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992, 35-6). Similar numerical codes are present in the first chapter of The Gift. They mimic Pushkin’s hidden clues and puzzles in QS, serving as cleverly concealed allusions. There are numerical codes that are explicit, i.e., three, seven and one in their straightforward numerical shapes and lexical forms, and also those that are implicit, i.e., ordinal numbers, morphological variants, and larger numbers occurring in the text. Larger numbers may appear unrelated to three, seven, or one, but through the addition method, used in ancient and modern numerology, larger numbers will be shown to yield three, seven, or one by adding the digits of numbers larger than nine; for example, the digits of the year 2009, when added together, yield two, e.g., 2009=2+0+0+9=11(1+1) =2.

At the opening of The Gift, the time is v isxode chetvortogo chasa (the end of the fourth hour) and the date is pervogo aprel’a 192- goda (the first of April, 192-). In Russian time-telling, 12:00-1:00 is perceived as the first hour on the clock, and therefore, the fourth hour refers to 3:00-4:00. The time at the beginning of the novel, therefore, is logically sometime after 3:30. The date contains a 1, but when added, equals seventeen, which graphically consists of the digits one and seven. Therefore, the time and date alone yield trojka, sem’ orka and tuz. An address mentioned shortly thereafter is nomers' em’ po Tannenburgskoj ulice (number 7, Tannenburg Street), while a moving van parked in front of it is described as having cin[ie] arshinn[ye] litr[i]' (dark blue arshin-high letters). An arshin is roughly equivalent to .77 of a yard, or 2.3 feet, but in the English translation from Vintage, the arshin is translated as “yard-high.. .letters.” Whether we consider the English translation, where one yard is equal to three feet, or the Russian measurement converted to yards or feet, it yields significant numbers, in conjunction with the semjorka in the street address. Additionally, there are 21 letters in the Cyrillic phrase for the street, which, when added, e.g., 2+1, yields a three, and 21 is also a multiple of seven and three.

[15]

In the neighborhood landscape depicted early in the first chapter there are “three red-necked husky fellows in blue aprons” (4), “three blue chairs” (7) and the monotonous layout of the city’s businesses require that the “green grocery...be at first seven and then three doors away from the pharmacy” (5).

In the first chapter Fyodor has just published a collection of okalo p’atidec’ ati dvenadcatistikhij (around fifty twelve-line) poems, i.e., not fifty poems exactly. If there are 49 (4+9=13, 7x7=49) poems, twelve lines each, then the total number of lines is 588, 5+8+8=2+1=3, or again, 21 is multiple of 7 and 3. The other possibility is that there are 52 (5+2=7, 17.333...x 3=52) poems, which would make 624 lines, (6+2+4=12=1+2=3). It is even more likely that there are 51 poems, because 51 is a multiple of 17 and 3, which provides all three of the numbers in question.

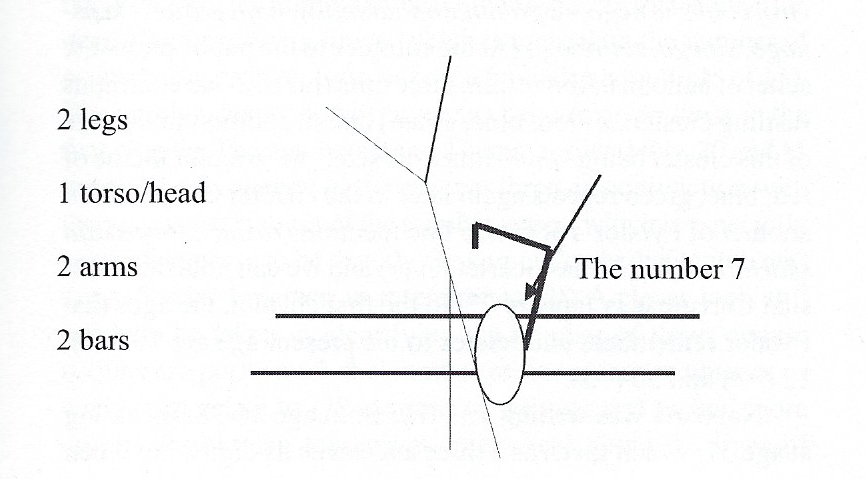

A description of a clown also has some numerical significance: Eto byl kloun...opiravshijsja rukami na dva bel’onyx bruska poka on podnimal...vyshe i vyshe nogi...i on uglovato zactyval (This was a clown...who was propping himself on two bleached parallel bars while he lifted his legs...higher and higher...and froze in an angular attitude). This image can be represented in the following way:

[16]

In this diagram, the image of the clown on the bars has seven parts: 2 legs 12 arms+2 bars+1 body (torso and head), which can be represented with seven lines forming one distinct ‘angular’ shape. Consequently, in this drawing, it is possible to see the number 7 (an angular number) formed by the bend in the clown’s left arm.

Fyodor says that he vyjexal s’em’ let tomu nazad (emigrated seven years ago) and calls the present year God S'em' (The Year Seven). If we go back to the original date presented at the onset of the novel, April 1, 192-, and if we change the year from 192- to “The Year Seven,” we have the numbers 4 (month) 1 (date), and 7 (“The Year Seven”), which, when added together, equal 3, and this in combination with the 1 of the date and the year “Seven,” provides another combination of trojka, sem' orka i tuz.

Fyodor’s birthday is July 12, 1900, which gives us the seventh month, and the date and year add up respectively to be 3 and 1. Commenting on his father, Fyodor says: zapertye na kl’uch tri zaly, gd'e naxodilis’ jego kollekcii, jego muzej (His collections, his museum, were locked up in three rooms). While remembering a scene from childhood Fyodor describes: U vxodav sad—javlenije: prodavec vozdušnyxšarov. Nad nim, vtroje bol’she nego, —ogromnaja shurshashchaja grozd’... krasnogo, sinego, zel’ onogo (At the entrance to the public park—the seller of balloons. Above him, three times his size-an enormous rustling cluster...of red, blue, green) and in addition to the size of this cluster being “three times his size,” the tricolor theme of red, blue, green repeats again later in the chapter in a poem. In another of Fyodor’s poems, a line mentions rozhd’ estvenskaja skarlatina (Christmas Scarlet fever) and we can note that Russian Christmas is January 7th. In the first chapter, the ages that Fyodor remembers and relates to his present age are 10 (=1), 12 (=3) and 30 (=3).

Nabokov was writing The Gift from age 36-38, including at age 37, which gives us a three and seven as digits, but when

[17]

added together, these equal one. Nabokov began writing The Gift in 1935, one hundred and one years after the publication of QS in 1834, and published it in Russian in 1938, one hundred and one years after Pushkin’s death in 1837, when Nabokov was 39 (=3 or 13x3). Pushkin was 38 at the time of his death, which parallels Nabokov’s stage in life during his writing of The Gift.

Multiple instances of cardinal and ordinal forms of three, seven, and one, for example, tri (three), troje (three [collective]), and tr’etij (third), are found in the Russian text. By including all of potential allomorphs, taking inflection, gender, spelling changes, and derivation into consideration, compared to the instances of similar forms for two and four, occurrences of the numbers three, seven, and one are more commonly found than other numbers. The word odin (one) and its allomorphs and compound words occur most frequently. This makes sense, not only due to the numerical significance of one, but because

in Russian, the word also functions as an indefinite article “a, an,” pronoun “one,” and the root for “one, alone, single” and other associated meanings, e.g., in the word odinokij (lone, solitary). (It remains to be determined which of the sixty-odd occurrences of the word odin and its variants are purely numerical, and which have other functions). The frequency of the occurrence of the number three is notable purely for its quantity, occurring twenty-six times, which is more than the number of occurrences for two, four, or seven (and also a multiple of 13). The number seven, however, occurs exactly seven times in the first chapter. The numbers 2 and 4 occur, respectively, 20 and 11 times. The frequency of the number three, in conjunction with the seven occurrences of the number seven, which is especially suspect, appears to be exactly the sort of “code that tantalizes” described by Emerson in reference to QS. A closer look still needs to be taken in identifying the number of times certain actions are performed, the number of times certain phrases or words that relate to QS are said or written, and to find more cryptic Pushkinian logogriphs in the text along the lines of

[18]

Sergei Davydov’s “utroiT USemerit’” discovery in Queen of Spades (“The ‘Ace’ in Queen of Spades,” Slavic Review, 58, 2, [Summer 1999], 314).

—Rachel Stauffer, Charlottesville, VA

CONJURING WINTER IN THE SUMMER

“Shade's poem is, indeed, that sudden flourish of magic: my

gray-haired friend, my beloved old conjurer, put a pack of index

cards into his hat—and shook out a poem.”

Charles Kinbote, “Pale Fire.”(Foreword)

‘‘But one must not let things tumble out of one’s

sleeves... ”

Vladimir Nabokov, 1946.

In two letters to Edmund Wilson, Nabokov twice mentions “Sherlock Holmes and snow” when referring to Kenneth Fearing’s poem, “Sherlock Spends a Day in the Country” (Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya, The Nabokov-Wilson Letters, 1940-1971, University of California Press, 2001, Letter 95, [March26,1944], and Letter 100 [June 9,1944]). This resonates with John Shade’s lines, in Pale Fire, “Whose spurred feet have crossed/ From left to right the blank page of the road?/ Reading from left to right in winter’s code [...] Was he in Sherlock Holmes, the fellow whose/ Tracks pointed back when he reversed his shoes? ” And yet, Nabokov’s novel would only gain shape several years later.

Although Nabokov repeated his praise of Kenneth Fearing’s verses (“There was a lovely poem about snow and Sherlock Holmes in one of the last New Yorkers” and, three months later,

[19]

“that wonderful poem about Sherlock Holmes and snow”), he fails to name or to place them in any specific edition. In his letter of March 26, he mentions Fearing in the same paragraph in which he tells Edmund Wilson about how much he “loved [his] article on magic,” but he doesn’t connect them, despite the elements in common between Wilson’s review of John Mulholland and the Art of Illusion, and Fearing’s poem “Sherlock Spends a Day in the Country,” (The New Yorker, March 11,1944).

Just as in The Real Life of Sebastian Knight’s reference to the nursery rhyme “Who killed Cock Robin,” about a conference of animals and a murder in Knight’s satire about detective novels, in Fearing’s poem we find the fantasy about a collection of spurs that suggest a conspiratorial project of assassination, an image which might in part explain Nabokov’s interest:

“Nevertheless, in spite of all this apparent emptiness, notice the snow;

Observe that it literally crawls with a hundred different signatures of unmistakable life.

Here is a delicate, exactly repeated pattern, where, seemingly, a cobweb came and went,

And here some party, perhaps an acrobat, walked through these woods at midnight on his mittened hands.

Thimbles and dice tracks and half-moons, these trade-marks lead everywhere into the hills;

The signs show that some amazing fellow on a bicycle rode straight up the face of a twenty-foot drift,

And someone, it does not matter who, walked steadily somewhere on obviously cloven feet.”

There are two different, not mutually exclusive connections to Conan Doyle’s character Holmes and his adventures in Pale Fire. For Priscilla Meyer (Find What the Sailor Has Hidden, Vladimir Nabokov's Pale Fire, Wesleyan University Press, 1988, 107), “the reference to Sherlock Holmes and the

[20]

cat-and-mouse game with the syllable mus suggests Conan Doyle’s “The Musgrave Ritual” in which the crown jewels of Charles I are unearthed.” Brian Boyd (Nabokov’s Pale Fire. The Magic of Artistic Discovery, Princeton University Press, 1999) directs the reader to “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” after dwelling on Shade’s lines about T.S.Eliot’s “Grim Pen” and Conan Doyle’s “treacherous Grimpen Mire.” Boyd maintains that, by “appropriating Eliot’s “grimpen,” with its Sherlock Holmes allusion and its echo of what had seemed a supernatural, demonic hound [...] Shade elegantly and wittily links Eliot’s two most ambitious poems” (193-94). Kinbote, though, in his note to line 27, dismisses any further conjectures about Shade’s reference to Sherlock, to conclude that “our poet simply made up this Case of the Reversed Footprints. ”

In his text about magic, Edmund Wilson mentions Conan Doyle quite independently of Fearing’s Sherlock poem: “the late Sir Arthur Conan Doyle gave a gratuitous endorsement to a mind-reader named Zancig who had never pretended to be genuine [...] the faithful of the spiritualist cult even insisted that Houdini himself, though for some reason he chose to deny it, performed his feats through supernatural agency.” According to Wilson, the chief pride of the magician is derived not from exploiting mechanical toys but from putting something over on his audience, and that you can be far more amazing with an ordinary coin, a piece of string, or a pack of cards than with a pocketful of gadgets [...] The whole matter of mystifying people is more interesting than may be supposed. A little acquaintance with the subject will afford a startling revelation of the common human incapacity to observe or report correctly; and anyone who has deluded an audience into believing that he was doing something which he had merely suggested to their minds, while he was actually doing something else that they were perfectly in a position to notice, will always have a more dubious opinion of the value of ordinary evidence. (91)

[21]

Wilson, a “non-apparitionist,” also writes appreciatively about John Mulholland’s book on the history of spiritualism, Beware Familiar Spirits when he mentions the “split between two groups of miracle-workers who grow more and more antagonistic” in the field of thaumaturgy: while the magicians expect praise for their conjuring talents and skills, the mind-readers and the mediums expect it for their display of supernatural powers. He considers that people often discard objective demonstrations about how the conjuring tricks operate in order to maintain their faith in the spiritual world. For Wilson, the undying enchantment provoked by magic results from “remnants of fertility rites. The wand is an obvious symbol, and has its kinship with Aaron’s rod and the pope’s staff that puts forth leaves in ‘Tannhauser’,” while Houdini “gave the impression of obeying some private compulsion to enact again and again a drama of death and resurrection.”

In contrast to Wilson’s skepticism, for Priscilla Meyer (“Dolorous Haze, Hazel Shade: Nabokov and the Spirits,” Nabokov's World, Volume 2: Reading Nabokov, Ed. Jane Grayson, Arnold B. Mcmillin, Priscilla Meyer, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, 2 vols.), “Nabokov’s faith in emanations of the beloved dead from the spirit world must have stemmed from his own encounter with his father as described in The Gift, as Vera Nabokov hints in her foreword to Nabokov’s verse. In his art, Nabokov’s faith in the possibility of the survival of the spirit after death is only subtly perceptible, like the spirits themselves whom it is his gift to see.”

The circumstantial connection between Fearing’s poem and Wilson’s article must have remained in Nabokov’s memory because both authors share ideas that appeal to him. Comparing Wilson’s review and Fearing’s verses, we see how “the common human incapacity to observe or report correctly” mentioned by Wilson, is echoed by Fearing when he suggests that Sherlock Holmes practices these rarely found abilities for perceiving details. Nevertheless, Fearing’s Sherlock applies his powerful

[22]

reasoning to clues he himself interprets in a distorted way.

In Pale Fire Shade is shown as a “conjurer” by Kinbote because, after shuffling index cards, he comes out with a poem dealing with illusions, reflexions and winter spurs. Spiritualist seances are described by Kinbote and Shade, as well as poltergeist phenomena and Hazel’s investigation of a moving light in the barn. For Priscilla Meyer (2002), “the quest for the otherworld by author and characters is carried on in a web of references to spiritualism that appear in both Shade’s and Kinbote’s writing. Nabokov alludes to at least five men who participated in the movement: James Coates, A.R.Wallace, Charles Kingsley, Andrew Lang, and Conan Doyle.” Fearing’s incriminating clues lead Sherlock to a deduction which is as unfounded as Kinbote’s ravings about an anti-monarchist plot in Zembla.

If the pleasure Nabokov found in Wilson’s and Fearing’s writings in The New Yorker stimulated him to return, years later, to what had fascinated him in 1944, then a new hypothesis about Pale Fire must be taken into account.

In Fearing’s lines we read:

“The crime, if there was a crime, has not been reported as yet;

The plot, if that is what it was, is still a secret somewhere in this wilderness of newly fallen snow;

... Nevertheless, in spite of all this apparent emptiness, notice the snow;

Observe that it literally crawls with a hundred different signatures of unmistakable life,

... consider this mighty, diversified army, and what grand conspiracy of conspiracies it hatched,

What conclusions it reached, and where it intends to strike, and when ...”

Is there a still unreported crime in Pale Fire? Is Shade actually dead when Kinbote grabs his cards and goes into hiding in

[23]

a Cedarn “cave”? Is the answer about Shade’s murder masked by Nabokov’s magic tricks, or by his faith in the supernatural?

Although it is difficult, if not impossible, to establish a clear connection or an indirect influence on the lines about “Sherlock and snow” in Pale Fire with Kenneth Fearing’s poem, read together with Wilson’s text mentioning Conan Doyle, Nabokov’s fascination with Fearing’s poetic images and his interest in Wilson’s review on magic suggest that he was haunted by themes whose transmutations we later find in his various novels, particularly in Pale Fire.

—Jansy Berndt de Souza Mello, Brasilia

PAINTERLY CONNOTATIONS IN THE ORIGINAL OF LAURA

The Original of Laura once again demonstrates the important role which painting plays in Nabokov’s oeuvre (for the most recent discussion of the subject, see Gavriel Shapiro, The Sublime Artist's Studio: Nabokov and Painting, Evanston, 111.: Northwestern University Press, 2009). Its very title has a painterly connotation. Furthermore, the existent storyline suggests that Flora served as the model for Laura of the novel in the novel: “Everything about her is bound to remain blurry, even her name which seems to have been made expressly to have another one modeled upon it by a fantastically lucky artist” (TOOL 85).

Laura, of course, evokes the name of Petrarch’s beloved, whose portrait the poet asked Simone Martini to paint (see sonnets 77 and 78) upon meeting the artist in Avignon. Morris Bishop, Nabokov’s Cornell colleague and friend, writes of this “small portable portrait” that “Petrarch carried it everywhere close to his heart” (Morris Bishop, Petrarch and His World,

[24]

Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1963,148). Among the best-known existent portraits bearing this name is Giorgione’s Laura (1506, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna).

Flora, the Roman goddess of spring and flowers, was revered by the ancients and celebrated with annual feasts, called Floralia, which took place between the end of April and the beginning of May. Images of Flora frequently adorned the interiors of Roman villas, as exemplified by the fresco from a villa in Stabiae (the National Archeological Museum, Naples). In Ada, this fresco is dubbed “the Stabian flower girl” (Ada 8).

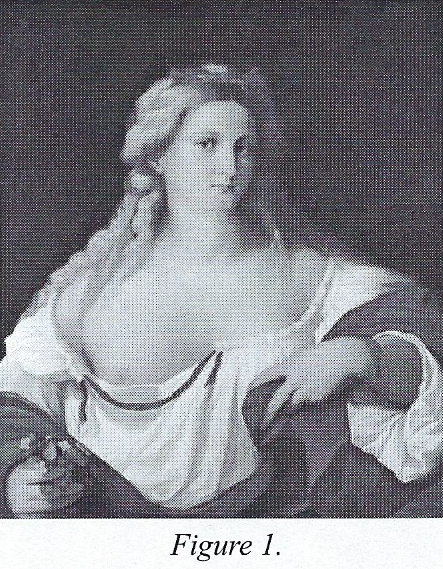

Curiously, in Ancient Rome, Flora was also “traditionally a name of courtesans” (Julius S. Held, “Flora, Goddess and Courtesan,” in De Artibus Opuscula XL: Essays in Honor of Erwin Panofsky, 2 vols., ed. Millard Meiss, New York: New York University Press, 1961, 1: 209), thereby tallying well with Nabokov’s eponymous heroine. Such depiction can be frequently found in the Renaissance, as, for instance, in Flora (ca. 1515, the Uffizi Gallery, Florence) by “[A] titillant Titian” (Ada 141), or in the painting by the same name, also known as A Blonde Woman (1520, the National Gallery, London) (figure 1) and believed to be related to Titian’s Flora, by Palma Vecchio. Nabokov mentions the artist by name in Ada (“A drunken Palma Vecchio”), while at the same time alluding to the painting—hence “a Venetian blonde” (ibid.). Nabokov was familiar with Palma Vecchio’s artwork from his childhood: the artist’s earlier painting. Madonna and Child (ca. 1515, now in the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg), adorned the Nabokov family home (see Shapiro, The Sublime Artist’s Studio, 15). Being interested in Panofsky’s studies (see AWL 354) and presumably being familiar with the aforementioned Panofsky festschrift, Nabokov could read therein Held’s essay which contains numerous representations of Flora, both as goddess and courtesan, and traces her imagery from the Renaissance to the Baroque era.

[25]

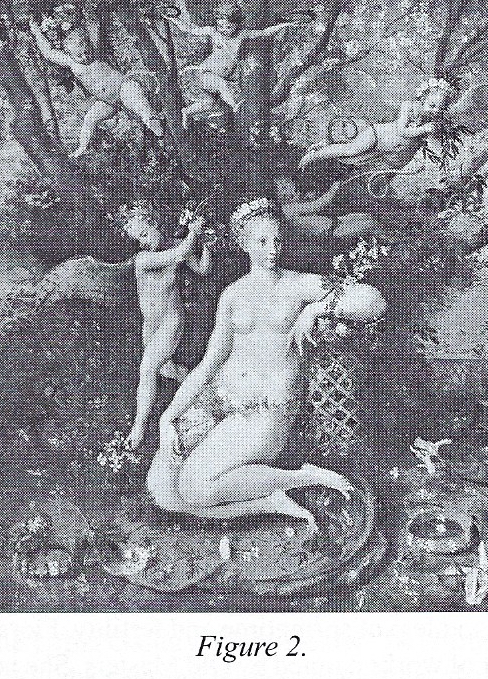

As the goddess of springtime and fertility, Flora is present in a number of works painted by Old Masters. She is one of the figures in Botticelli’s Primavera (ca. 1482, the Uffizi Gallery, Florence). It is to Botticelli’s Flora—“the fifth girl from left to right, the flower-decked blonde with the straight nose and serious gray eyes” (LATH 107)—that Vadim Vadimovich likens Annette in Look at the Harlequins! The goddess is the main subject of a Fontainebleau School painter, appropriately called Master of Flora, specifically in his The Triumph of Flora (ca. 1560, private collection, Vicenza) (figure 2; cf. Held, 2:70). Nabokov possibly alludes to the Fontainebleau School and specifically to this painting by mentioning Flora bicycling “through the Blue Fountain Forest” (TOOL 83), “the Blue Fountain” being the literal translation of Fontainebleau (see Gennady Barabtarlo’s comment to his Russian translation of The Original of Laura in Vladimir Nabokov, Laura i ee original, St. Petersburg, Azbukaklassika, 2010, 64n 14). Similarly to the deity in this painting, Nabokov’s character has smallish breasts.

[26]

Getting closer to Nabokov’s own time, we find Flora depicted, not uncommonly, as a young girl, or with a maidenly figure. Thus, Pre-Raphaelites, who were especially influenced by Botticelli, frequently depicted Flora in this manner. Among them, John William Waterhouse deserves a special mention. He shows Flora as a dreamy-looking dark-haired young girl in a white dress (1891, private collection) (figure 3). Nabokov could come across Waterhouse’s piece in R. E. D. Sketchley, “The Art of J. W. Waterhouse, R. A.,” The Art Journal, Christmas Number, 1909,7. Even if Nabokov did not familiarize himself with Waterhouse’s canvas, it is still illuminating to notice the similarities between the painter’s depiction of Flora and Nabokov’s portrayal of his eponymous character.

[27]

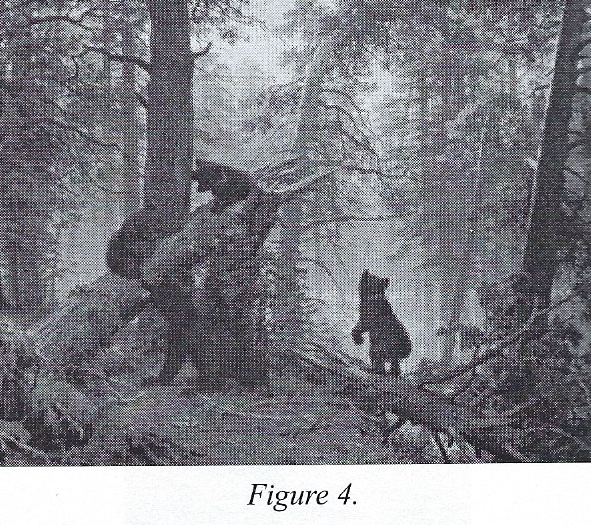

Moving away from portraiture and to Nabokov’s native country, we come across the expression of the writer’s characteristic disdain for both the Wanderers (Peredvizhniki) and the Academicians. This disdain is manifest in the narrator’s attitude toward Flora’s grandfather, Lev Linde, a landscape painter. (We recall that Nabokov was especially receptive to this genre, as he himself aspired to become a landscape painter in his boyhood and early youth). The narrator reports that “Native ‘decadents’ [presumably a reference to The World of Art group] had been calling them [Linde’s works] ‘calendar tripe’” (TOOL 43). The initial description of Linde’s artwork, “clearing in pine woods, with a bear cub or two” (TOOL 41), unmistakably points to

[28]

Morning in the Pine Forest (JJtro v sosnovom boru, 1889, the State Tret'iakov Gallery, Moscow) (figure 4) by Ivan Shishkin, whose last name Nabokov slightingly misspells as Shishkov in his Russian memoir (Ssoch, 5: 288).

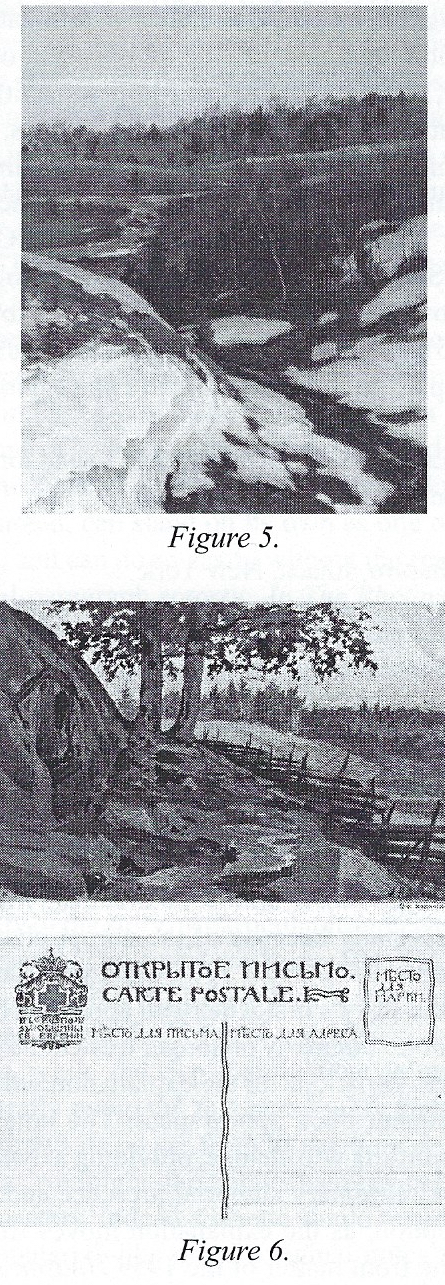

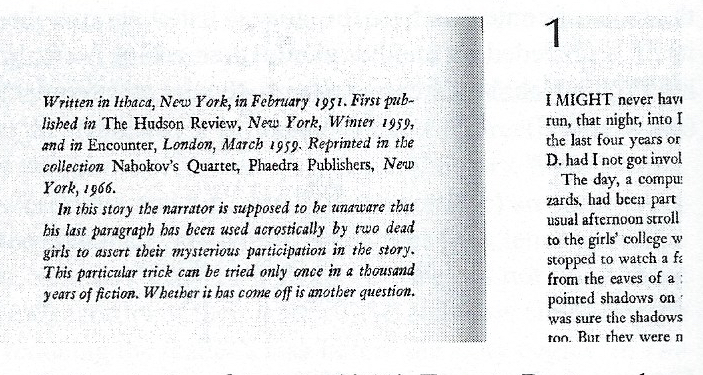

The two additional descriptions, “brown brooks between thawing snow-banks” and “vastness of purple heaths” (ibid.), sound more generic. The first example, however, brings to mind the paintings by Konstantin Kryzhitsky, and specifically his canvas Early Spring (Ranniaia vesna, 1905, the State Tret'iakov Gallery, Moscow) (figure 5), whereas the second evokes Albert Benois’ In Finland that Nabokov could have seen reproduced on the St. Eugenia Society postcard (figure 6). We recall Nabokov’s scornful remark about Kryzhitsky’s other canvas, “A Thawed Patch [...], where nothing thawed” (‘“Protalin[a]’ [...], gde ne taialo nichego”), and about Albert Benois’ artwork, which he dubs “dead stuff’ (mertvechina) (Ssoch, 5:172).

[29]

[30]

The Original of Laura contains a fascinating twist: in the mock-autobiographical mode, reminiscent of Look at the Harlequins!, Nabokov bestows self-referential titles on Linde’s pitiable paintings. Thus, “April in Yalta” points, of course, to Nabokov’s birth month and to his stay in the Crimea, while together alluding to the story “Spring in Fialta.” “The Old Bridge,” on the other hand, suggests Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev’s poem “The Swift” (Gift 94) that contains the old bridge image (see also Barabtarlo’s comments to Nabokov, Laura i ee original, 165). This brief survey suggests that the fine arts were designed to play an important role in The Original of Laura.

I thank Luba Freedman and Tatiela Laake for their helpful comments on this note.

—Gavriel Shapiro, Ithaca, New York

CYNTHIA’S BROKEN SERIES: THE HEREAFTER’S TEXT AND PARATEXT IN

“THE VANE SISTERS”

When Katherine White rejected “The Vane Sisters” in 1951, Nabokov defended the story’s last-paragraph acrostic by insisting that “the reader almost automatically slips into this discovery, especially because of the abrupt change in style” (Selected Letters: 1940-1977, 117). Eight years later, however, he prefaced the story’s first American appearance with a brief explanatory note. Nabokov no longer trusted the reader to slip into discovery. Variations on the explanation will recur in the story’s subsequent book appearances. The note’s place will shift and its wording will change, providing a dynamic view of Nabokov’s extraordinary authorial presence and control over his own reception, as the explanation moves from its initial iteration in the front matter of the 1959 Hudson Review to its

[31]

first book appearances in 1966's Nabokov’s Quartet and 1975’s Tyrants Destroyed and Other Stories. The various notes guide how the story is read, and thus fit Gérard Genette’s definition of a paratext (Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997). Nabokov’s explanations may exist just outside of the text, but they determine its reading,

This last statement bears repeating because (with some exceptions) “The Vane Sisters” does not appear in print without a variation of its accompanying explanatory note. The explanation cannot be separated from the story, but as readers we are trained to regard material outside the text as a supplement, all the more so in the case of “The Vane Sisters,” a story rightly regarded as one of Nabokov’s most accomplished short works.

“The Vane Sisters,” as Wayne Booth, Brian Boyd and other critics have noted, can stand on its own as one of Nabokov’s finest efforts, and can do so easily without the reader catching on to the final-paragraph acrostic. In The Rhetoric of Fiction, Booth was among the first to shed light on the “Vane Sisters’” narrator’s consistent unreliability and unawareness, making the acrostic just one of many places where Nabokov establishes a direct line of communication with his readers. The narrator is a faulty filter; the fault lines telegraph differences in attitude and knowledge between author and narrator, a technique Nabokov uses with Lolita's Humbert and John Ray, Pale Fire’s Kinbote, and elsewhere. Boyd is particularly good at pointing out the sensory beauty of the story, in particular its precision in etching winter landscapes {The American Years, 194). So the explanatory note does not need to be there for the story to exist, or for it to exist as an unqualified literary success.

However, while the explanatory note is quite properly and quite literally marginal, this marginality matters, because the paratext draws its power from its seeming invisibility and because – try as we might – the paratext simply cannot be separated from the story. Indeed, Genette would regard Nabokov’s explanatory material-like other “original notes to discursive

[32]

texts” – as belonging to the text proper: these notes “constitute modulations of the text and are scarcely more distinct from it than a phrase within parentheses or between dashes would be” (Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, 342).

This indivisibility of text and paratext guides our reading: once a reader knows of the acrostic, there is no going back, and while it is theoretically conceivable to skip the note, whether by accident or choice, it is actually quite difficult to do so in practice. In this regard, the “Vane Sisters” note is singular to Nabokov’s work, a key to decoding a story element-a direct intervention from Nabokov himself, and not from a Nabokov-like presence (the personae who make sporadic appearances in, for example, Bend Sinister, “Cloud, Castle, Lake,” or Pnin). The note is also the manifestation of a form often parodied by Nabokov; elsewhere, explanatory notes are usually penned by John Rays, Charles Kinbotes or Vivian Darkblooms. These “fictional notes, under cover of a more or less satirical simulation of a paratext,” Genette remarks, “contribute to the fiction of the text except when they constitute that fiction through and through, such as those of Pale Fire” (343).

The note is an implicit admission that Katherine White was right. Nabokov’s explanation even indirectly addresses White’s response toNabokov’s defense: the story, White claims, leaves her cold, and the style (and the acrostic) are more work than the characters are worth. She writes (in a letter quoted in full in Nabokov’s Selected Letters), “We did not think these Vane girls worthy of their web” (118). Nabokov simplifies the web, reducing the reader’s task before the story begins: in The Hudson Review, the explanation is embedded in the magazine’s “Notes on Contributors,” which reads: “Vladimir Nabokov’s book of short stories, Nabokov s Dozen, is reviewed in this issue. Puzzle-minded readers of the ‘The Vane Sisters’ may be interested in looking for the coded message that occurs on the last page of the story” (see Figure 1).

[33]

Figure I: Nabokov in the “Notes on Contributors ’’ front matter of Encounter’s 1959 issue

The note doesn’t just precede the story: it also precedes the table of contents where the story is listed, though the note itself is preceded by another paratext: an ad for Lolita which highlights Nabokov’s extraordinary change in circumstances (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Lolita ad in the 1958 Encounter issue

Eight years earlier, in his correspondence with White, Nabokov explains that he was disappointed by the rejection partly because he was in “awful financial difficulty”; eight years later, he is the bestselling, critically claimed author of a succès de scandale, a man whose fame precedes him; note the

absolute lack of biographical detail in The Hudson Review's “Notes”; the journal safely assumes that any reader would know Nabokov (whereas the other two contributors sharing the column are described and qualified: one is “the eminent Scottish poet,” the other the “Hudson Review Fellow in Fiction”). Nabokov himself needs no introduction; “The Vane Sisters,” however, does.

And the need to introduce “The Vane Sisters” persists: a variation of the explanatory note also appears in the last version to be published during Nabokov’s lifetime, the 1975 edition of Tyrants Destroyed and Other Stories (Figure 3), where the explanation is far more explicit than its initial 1958 iteration. Following a paragraph outlining the story’s publication history,

Nabokov writes: “In this story the narrator is supposed to be unaware that his last paragraph has been used acrostically by two dead girls to assert their mysterious participation in the story. This particular trick can be tried only once in a thousand years of fiction. Whether it has come off is another question” (218).

Figure 3: Paratext and text in 1975 s Tyrants Destroyed on pages 218 and 219 respectively, so that the acrostic in the final paragraph is telegraphed before the story begins

The note appears opposite the story’s beginning – it has moved closer since the intermediate 1966 iteration, the Foreword to Nabokov s Quartet, so while the language is nearly identical,

[35]

it is now difficult, if not impossible, to miss the information. Moreover, the reader no longer has to look at the entire last page; Nabokov has not only reduced the hunt to the relevant last paragraph, but he has also made interpretation even easier on the reader, not just “puzzle-minded” readers, by pointing out the acrostic nature of the puzzle.

Also embedded in the note is a self-effacing, jocular critique of this type of “trick”: that it should be done rarely, if at all, and that he (Nabokov) isn’t actually sure that the trick comes off, with the implication that if anyone can do something of this sort, it would be Nabokov, and that of course–of course–it comes off. The note’s humorous expression of doubt comes close to preterition, where one does something by claiming that one isn’t doing it (or, in this case, that one has doubts as to whether it can be done, or has been done successfully). This self-effacement helps the paratext, since the note needs to simultaneously convey important information about the narrative while also addressing the note’s intrusiveness; the note effectively disarms itself in those last two sentences, first via hyperbole (“once in a thousand years of fiction”) and humor (don’t try this at home), and then by dismissing itself altogether: “Whether it has come off is another question” is another way of saying, But never mind that, on with the story. Nabokov has created a frame for the narrative (look for the acrostic) that stresses the centrality of that frame for the narrative (again: look for that acrostic) by focusing on Katherine White’s own concerns (has the acrostic has come off?).

So effective is this frame that it is difficult not to take the paratext at its word, or (for some critics) to actually take the words from the paratext for the title, either directly from the explanatory note or from the correspondence pertaining to the story. (See Ristkok, Tuuli-Ann. “Nabokov’s ‘The Vane Sisters ’—‘Once in a Thousand Years of Fiction,” The University of Windsor Review 11 (1976), 27-49; Wagner-Martin, Linda: “The Vane Sisters’ and Nabokov’s ‘Subtle and Loving’ Read-

[36]

ers,” Torpid Smoke: The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov. Eds. Steven G. Kellman and Irving Malin. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Rodopi, 2000; and De La Durantaye, Leland, Style is Matter: The Moral Art of Vladimir Nabokov. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 2007). The paratext guides the reader–subtle or not, loving or not-–toward the pattern embedded in the story, one intricately tied to issues explored by De La Durantaye, but also with issues of the afterlife explored by Connolly, Alexandrov, and Brian Boyd.

The paratext’s intent mirrors that of the acrostic. The acrostic confirms Cynthia and Sybil’s existence in the hereafter, so that the boundary between one world and the other is blurred and illusive. The paratext clarifies and validates the means through which these boundaries are blurred and shown to be illusory. Cynthia and Sybil assert their control over the story’s events (and the story’s narrator) through the acrostic, and Nabokov asserts his control over his readers by guiding them to that solution.

The paratext, like the beginning to Nabokov’s biography of Gogol, points us to the very end of the narrative, where the ghosts conjured at the beginning wait to tell us they’ve been with us all along. Both paratext and acrostic ultimately reach the reader, but the former makes explicit what the latter only suggests: that reading and writing can seriously engage with intimations of the hereafter by creating elaborate simulacra that teem with encoded meaning. Nabokov becomes the mediator of and the center from which this meaning is made. “The Vane Sisters’’ pivots on his paratext, but this particular mediation is only an explicit manifestation of a technique implicit throughout Nabokov’s body of work: the mechanisms embedded in Nabokovian prose orient the reader toward Nabokov and align the reader with Nabokov. Nabokov’s rhetorical arsenal-para-text included-serves to turn what Amy Reading calls “critical analysis into readerly compliance” (“Vulgarity’s Ironist: New Criticism, Midcult, and Nabokov’s Pale Fire, ” Arizona Quarterly, Summer 2006, 80). We are meant to find what the sailor

[37]

has hidden, but this is very much a guided search; the sailor controls what we’re looking for, what we’ll find, and what we can do with it.

—Juan Martinez, Las Vegas, Nevada

GRADUS IN THE PALE FIRE INDEX

The entry for Gradus, Jakob in the index to Pale Fire gives “a Jack of small trades and a killer, 12, 17” as his first appearance in the commentary. The convention of the Gradus entry is to include only those of Kinbote’s notes in which he refers directly to Gradus by name (in every case except the note to line 949-1, where he is “the thug in New York”), omitting the occasions when he hides behind an anagrammatical or other disguise. One of his disguises, “Tanagra dust” is indexed and identified as “his name in a variant,” but this disguise, unlike anagrams such as d’Argus (note to line 47-8, not indexed with Gradus), leaves his name essentially intact, and the name Gradus also appears undisguised later in the same note. Tanagra

dust is also in the next note (to 597-608), which is not indexed under Gradus. Also absent from the index is his name in the note to lines 1-4, but the reason for this is clear: only the names Charles II; Kinbote, Charles, Dr.; and Shade, John Francis are indexed under the initial note, with everything else (Gradus, Onhava) excluded.

Gradus’s real introduction comes in the note to line 17, and that as well as all sixteen subsequent instances of his name are dutifully recorded. Only the note to line 12 presents a problem in finding Gradus, who appears there neither by name nor under any alias; this is the sole occasion when he is indexed but not readily found.

Actually, Gradus has been hidden in at least two places in this note. The description of Zembla under the reign of Charles

[38]

II observes that “A small skyscraper of ultramarine glass was steadily rising in Onhava” (75). Since Gradus is a glassmaker (e.g., note to line 17) and described by the index as “a Jack of small trades,” it is likely that he is working on this oxymoronic small skyscraper. (“Gradually rising” would apparently have been too easy a clue). This may seem sufficient, but the solver who stops here will miss Gradus’s second, more difficult, hiding place:

ANGUS MACDIARMID --> GRADUS, ICI MADMAN

This anagram can only be solved using the language of Pale Fire, where the ICI is the Institute for the Criminal Insane, from which Jack Grey has escaped. The reader is alerted to the importance of the acronym when madman Jack Grey gives his residence as the “Institute for the Criminal Insane, ici” (295, original italics). Is it possible that the anagram is unintentional? This would require that the anagram not only occurred by chance but also did so in the only note in the entire commentary in which the reader has been given the task of searching for Gradus; as Kinbote says, “The odds against the double coincidence defy

computation” (260).

It is impossible to interpret why Gradus is hiding behind Angus MacDiarmid without knowing who planted the anagram. It is no coincidence that this question of authorship is raised in the note to line 12, in which Kinbote gives two lines supposedly stricken from Shade’s draft, which he later admits were his own invention (note to line 550). If Kinbote is aware of the anagram and planted it himself, it could be a very well concealed concession that his Gradus is fictional and that escaped madman Jack Grey is the real killer; this would be an appropriate counterpart to the concession he makes about the two lines he counterfeits. However, given that Kinbote says he leaves those lines in his commentary because to delete them “would mean reworking the entire note...and 1 have no time

[39]

for such stupidities” (228), one may not want to ascribe such an elegant puzzle to him. It seems more likely that the author, in true Nabokovian style, is contradicting his own character’s statement that “it is the commentator who has the last word” (29) by claiming it for himself. This is the point of the double solution to Gradus’s hiding place: if Kinbote wrote the index, the only way Nabokov could deceive his character without undermining the accuracy of the index was to hide Gradus where he was already hidden. Thus, Kinbote records a glass skyscraper in his index as a reference to Gradus, aware of neither the madman concealed in his hypothetical university lecture nor of the greater composition directed by the master.

—Alex Roy, Middletown, Connecticut

NOTES ON A FAMOUS FIRST LINE (“LIGHT OF MY LIFE”)

Some Nabokovians wonder whether every significant phrase in Nabokov, and many an insignificant one, deliberately echoes important moments in the literary tradition. Others wonder whether these echoes matter at all. Still, these moments, when discovered, invariably shed some light on the given work—even if this illumination simply shows that Nabokov was aware of and either valued or contested how prior artists had treated similar themes. One phrase that has been awaiting scrutiny is the first sentence of Lolita's Chapter One, which, it seems, must have a precursor. And it does, indeed it does.

The expression “light of my life” has probably long been a cliché, with religious use dominating in pre-modern times, and on its own it would not have made for much of a stylistic triumph if Humbert Humbert had not quickly appended the words “fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo lee-ta. ..” But it

[40]

turns out that the shopworn phrase has an interesting history that includes at least one, and maybe three, works that might have attracted Nabokov’s eye and ear. There are also many works deploying the expression that are of no real interest whatsoever.

My search was conducted primarily within texts contained in Project Gutenberg and Google Books (and secondarily on other full-text resources on-line). As a result, there is some limitation of texts that are not in the public domain (although Google Books provides results of books under copyright, as well), and of course the search excludes older books not thought worthy of preservation in either digital archive. Still, a majority of “classic” and canonical literature is available to search in this manner. I also searched for several non-English equivalents.

The earliest use of the phrase apparently occurs in Euripides’ play Andromache. In most translations, the words are spoken by the title character as she surrenders herself to execution by Menelaus in exchange, as she believes, for her young son Molossus, whom she calls “my babe, light of my life” (E. P. Coleridge translation, http://classics.mit.edu/Euripides/andromache.html. The original ancient Greek was “Eye of my life,” cf. line 406, “ophthalmos biou.” The several English translations I have checked all use “light of my life,” as does, curiously, the modem Greek translation on Project Gutenberg, by George B. Tsokopoulos in 1910, http://www. gutenberg.org/etext/27592: “fos tis zois mou.” The French translation in the Belles Lettres edition preserves “eye”: “l’oeil de ma vie” [tr. Louis Méridier, Euridipe, Tragédies, Tome II, Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2003]). A few thematic points are obviously relevant; these will be discussed further on.

Another intriguing, but not perfect, match came from Sir Richard F. Burton’s verse translation of Catullus LXVIII (“To Manius on Various Matters) in 1894, where the phrase is used twice. This source is in some ways especially attractive, since Catullus is referred to explicitly elsewhere in the novel. On the other hand, the subject matter of this epistle is not especially

[41]

resonant with Lolita’s themes, and moreover, the accompanying Latin text and prose translation, by Leonard C. Smithers, make clear that the original phrase is simply “my light”:

Aut nihil aut paulo cui turn concedere digna

Lux mea se nostrum contulit in gremium,

Quam circumcursans hinc illinc saepe Cupido

Fulgebat crocina candidus in tunica.Worthy of yielding to her in naught or ever so little

Came to the bosom of us she, the fair light of my life,

Round whom fluttering oft the Love-God hither and thither

Shone with a candid sheen robed in his safflower dress.

(ll.131-34)

___________________________________________

Et longe ante omnes mihi quae me carior ipsost,

Lux mea, qua viva vivere dulce mihist.Lastly than every else one dearer than self and far dearer,

Light of my life who alive living to me can endear,

(emphasis added, ll.159-60)

(The Carmina of Caius Valerius Catullus, Sir Richard F. Burton and Leonard C. Smithers, trans. [London, 1894]; at Project Gutenberg: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/20732/20732-h/20732-h.htm .

By far the most alluring precursor appears in Sir Philip Sidney’s sonnet cycle Astrophil and Stella. This cycle chronicles the lyric hero’s frustrating love for and courtship of the beautiful, and married, Stella. At the beginning of Sonnet 68, we read:

Stella, the only planet of my light,

Light of my life, and life of my desire,

Chiefe good, whereto my hope doth only aspire,

[42]

World of my wealth, and heav’n of my delight:

Why dost thou spend the treasures of thy sprite,

With voice more fit to wed Amphion’s lyre,

Seeking to quench in me the noble fire.

Fed by thy worth, and kindled by thy sight?

(The Poems of Sir Philip Sidney, William A. Ringler, Jr., ed. [Oxford, UK: 1962], 163-238).

At this stage of the cycle, Astrophil, who early on professed an idealized love for Stella, has been struggling with stronger and stronger carnal desires. In stanza 63, he had cleverly interpreted her reply of “no, no” to his request for a kiss as a double negative, grammatically indicating her assent. Stanza 71 ends with the lines

So while thy beautie drawes the heart to love,

As fast thy Vertue bends that love to good:

“But ah,” Desire still cries, “give me some food.”

Still she does not submit to his wish, and in the cycle’s second song, between sonnets 72 and 73, Astrophil describes waiting for her to fall asleep. While she sleeps, he kisses her on the lips, apparently with some passion:

Yet those lips so sweetly swelling

Do invite a stealing kisse:

Now will I but venture this,

Who will read must first learne spelling.

Oh sweet kisse. But ah she is waking. 25

He quickly regrets that he stole so little (since a second opportunity is unlikely); Stella, apparently, is furious. He later suggests, asking for another kiss, that he “nevermore will bite” (sonnet 82), raising questions about the severity of his intrusion.

[43]

The phrasing and rhythm of the first four lines of sonnet 68 seem very strongly to anticipate Humbert’s opening intonations. No other example 1 have found, in any text, mimics the echoing “Light of my life, ____ of my ____ ” formula that Sidney and Nabokov both employ (Sidney repeats the “____ of my ____ , ____ " of my parallelism in line 4 of the same sonnet). However, it is the thematic environment that speaks loudest for connecting this cycle to Nabokov’s novel. A forbidden love with supposedly ideal but also very real physical dimensions, and a kiss stolen during sleep: Humbert had intended slightly different caresses for his object, but on the whole his plan is parallel to Astrophil’s, albeit unfulfilled while Dolly sleeps. Again subtly anticipating Humbert, Astrophil’s story ends with sonnets lamenting Stella’s absence from him, but also calling her “my only light” (sonnet 108). Additionally, “Stella Fantasia” among Dolly’s classmates (AnLo 52), and “Gray Star” (4) as her destination, both seem to evoke in some strange way the star theme embodied in Sidney’s title characters.

To return briefly to Andromache, the theme of a doomed child, separated from its doomed parent, stands forth as a possible link between these works (although mother and child are eventually spared in the Euripides’ play), as in this early reference the phrase “light of my life” refers to the heroin’s “babe.” It is probably coincidence that Nabokov’s version uses the phrase to apostrophize simultaneously both a beloved female and a doomed child, who are in Dolly’s case the same person. Some circumstantial support for authorial intention appears in the fact that Humbert’s second phrase, “fire of my loins,” derives from a blend of the common locutions “fruit of my loins,” which clearly refers to offspring, and “fire of my heart” (ardor cordis), which relates specifically to passionate love; both of these produce generous sets of results in full-text searches (searching “loins” in full-text archives produces far more fruit than fire: Nabokov’s phrase appears to be unique; searching “fire of my” is mostly linked with “heart”; second place

[44]

goes to “soul”). That Humbert’s second phrase, too, combines parental love with erotic passion suggests that Nabokov may well have been aware of the dual usage of “light of my life” in earlier literature. In any event, both of these phrases turn out to be surprisingly apt in their allusive potentials.

Perhaps others with better knowledge of Classical literature and Elizabethan poetry will be able to refine my suggestion, or find deeper implications for the connections proposed here.

—Stephen Blackwell, University of Tennessee, Knoxville