Download PDF of Number 66 (Spring 2011) The Nabokovian

Number 66 Spring 20

____________________________________

CONTENTS

News 3

by Stephen Jan Parker

Nabokov and the Transnational Canon 7

by Rachel Trousdale

Notes and Brief Commentaries 15

by Priscilla Meyer

“A Humber Source of Humbert: More On 15

Nabokov’s Bicycles”

– Victor Fet and David Herlihy

“Pale Fire and Doctor Johnson” 21

– Gerard de Vries

“Nabokov-Chukovsky Controversy: The 30

Oscar Wilde Episode”

– Gavriel Shapiro

“Annotations to Ada’s Scrabble Game” 34

– Alexey Sklyarenko

“Deflowering the Myth in Zephyr and 44

Flora in Nabokov’s The Original of Laura”

– Yannicke Chupin

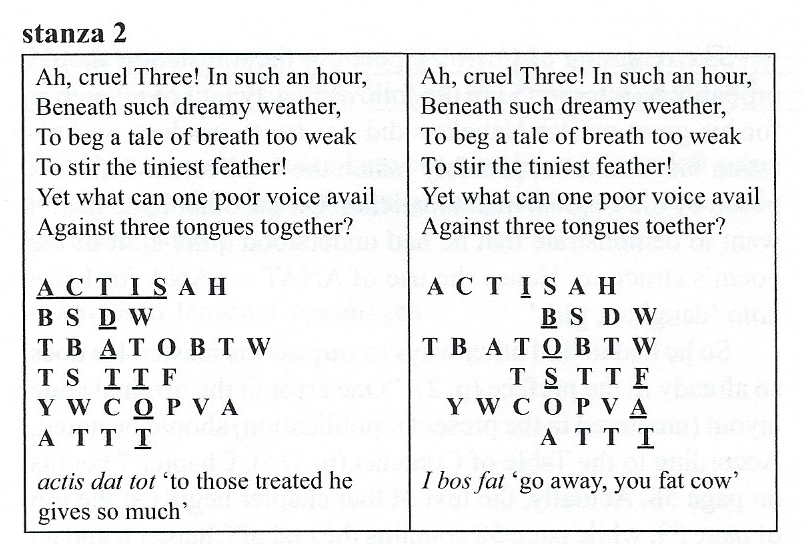

“The Case of the Missing Poem: Nabokov’s 51

Homage to Carroll”

– Jens Juhl Jensen

Annotations to Ada 32: Part 1 Chapter 32 56

Second Section

by Brian Boyd

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number XX, except for:

- Brian Boyd’s “Annotations to Ada” (because superseded by, updated, hyperlinked and freely available on, his website AdaOnline).

[3]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

Thus far in 2011, the Society has 114 individual members (77 USA, 37 abroad) and 80 institutional members (67 USA, 13 abroad). This is a smaller number than last year at this time, when it was 125 individual members and 87 institutional members. It is an upsetting drop. In the past the continuing existence of the

Vladimir Nabokov Society and The Nabokovian has been due largely to the magnanimous, substantial donations given to the Society by Dmitri Nabokov, to whom we have been indebted and most grateful. But the ongoing future of the Society and this publication is now in question. The incoming revenue at this point will not cover the on-going, growing costs.

*****

The Nabokovian takes pleasure in congratulating Evgenii Borisovich Belodubrovskii on his 70th birthday, which he celebrated in Petersburg on April 12th. Evgenii Borisovich has been an invaluable resource to Nabokovians and other scholars for many years, generously sharing his discoveries, detailed knowledge of bibliographic resources, and memoirs of literary figures. Evgenii Borisovich first learned of Nabokov's existence in 1964 when he discovered a packet of elegant little books tied with a broad ribbon on which was embossed «Tenishev poets» in the secret bookcase of the sculptor Leonid Abramovich Mess (a «dandy» in tweed jacket and corduroy trousers). Among these was the collection of Nabokov's poems published in 1916. Mess told him that this Volodia was now one of the best-known Russian writers in Europe, and that he had been bom next door

[4]

to Evgenii Borisovich on the Moika. A graduate of the Literary Institute (Literatumyi Institut), a high school for aspiring writers, Evgenii Borisovich calls himself an autodidact in the field of literary scholarship, a romantic «prospector». He worked in television, then in the Cultural Foundation (Fond kul'tury), and after retirement, as an associate of St. Petersburg University, teaching literature at the secondary school associated with the University, the “Academic gymnasium” school; he has also taught a course, «In Quest of Nabokov,»in the newly-founded Petersburg RGGU.

His many discoveries of manuscripts include Nabokov's translation of Alfred de Musset's «La nuit de Décembre» from a Tenishev literary magazine, «Young Thought» (Iunaia Mysl’); he was instrumental in arranging for the Russian translations of Brian Boyd's biography and Don Barton Johnson's book, and, together with Natalia Tolstaia and Vadim Stark, for placing the plaque commemorating Nabokov's birth at 47 Morskaia (hung on a rainy day after prolonged arguments with the city authorities and the intervention of Dmitri Nabokov); he published some of Nabokov’s letters to Gleb Struve, from the Struve archive in the Hoover Institution, in «Zvezda». He also edited, together with Natalia Tolstaia and Maria Malikova, a long epistolary exchange between Natalia Tolstaia and Elena Sikorski (née Nabokov) (Nabokov Online Journal. 2010. Vol. 4. (http://etc.dal.ca/noj/articles/volume4//10_Tolstaia_Final.pdf).

Evgenii Borisovich is a friend of the Nabokov Museum, and of Nabokov’s devotees. We send him our collective thanks for his services to Nabokov scholarship as well as our best wishes on his birthday.

[5]

Odds & Ends

– Brian Boyd would like to announce an international Nabokov conference, “Nabokov Upside Down,” to be held at the University of Auckland on January 10-13 2012, at the height of the pleasantly mild New Zealand summer. The keynote speaker will be Professor Robert Alter (Hebrew, Comparative Literature) of the University of California at Berkeley.

For the occasion of the first Nabokov conference “down under” we invite participants to consider Nabokov upside down, from a fresh perspective, but without losing their balance. Some quotes from Nabokov may provide springboards: this constant shift of the viewpoint conveys a more varied knowledge, fresh vivid glimpses from this or that side. If you have ever tried to stand and bend your head so as to look back between your knees, you will see the world in a totally different light. Try it on the beach: it is very funny to see people walking when you look at them upside down. They seem to be, with each step, disengaging their feet from the glue of gravitation. . . (Lectures on Literature) as I turn my life upside down so that birth becomes death (The Gift) “Oh, he’s an all-round genius. He can play the violin standing upon his head, and he can multiply one telephone number by another in three seconds, and he can write his name upside down in his ordinary hand.” (The Real Life of Sebastian Knight)

The conference website is http://www.nabokov2012.co.nz

-A particularly intriguing publication is Vladimir Nabokov and the Art of Play, by Thomas Karshan, Oxford University Press. Two other recent publications brought to our attention are (1) Lila Azam Zanganeh, The Enchanter: Nabokov and Happiness, Norton Press and (2) in French, Aux Origines de Laura: Le

[6]

Dernier Manuscrit de Vladimir Nabokov by Yannicke Chupin and Rene Alladays, Presses Universitaire de Paris.

*****

As I have done for the past 31 years, I wish once again to express my greatest appreciation to Ms. Paula Courtney for her essential on-going assistance in the production of this publication.

Nabokov and the Transnational Canon

by Rachel Trousdale

What do Zadie Smith, Orhan Pamuk, Michael Chabon, Myla Goldberg, W.G. Sebald, and Azar Nafisi have in common? Not native language, country of origin, life history, or religion. But they share an intellectual lineage: all of those writers cite similar influences, with Vladimir Nabokov high on the list. Their shared response shows us Nabokov’s central place in an emerging transnational canon, one in which communities of readership trump national or ethnic affiliations. For writers who want their work to transcend the limits of national or ethnic groups, Nabokov provides both a model and a point of reference, an ancestor in an affiliative intellectual family whose boundaries are marked not by geography or language but by a shared approach to self-invention and playful communication. This paper extends the argument of my recent book Nabokov, Rushdie, and the Transnational Imagination (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010) to show how broad the range of Nabokov’s influence is among contemporary boundary-crossing writers.

Nabokov is an intimidating model for a young writer. Zadie Smith argues that Nabokov’s power comes from his ability to turn readers into versions of himself:

He claimed to be writing ... ‘mainly for artists, fellow-artists and follow artists,’ whose job it was to ‘share

not the emotions of the people in the book but the emotions of its author—the joys and difficulties of creation’.

Follow artists! In practice this means subsuming your existence in his, until you become, in effect,

Nabokov’s double, knowing what he knows, loving what he loves and hating his way, too... [here Smith

inserts a footnote: Nabokov nerds often

[8]

slavishly parrot his strong opinions. I don’t think I’m the first person to have my mind poisoned, by Nabokov,

against Dostoevsky.]... It is a reversal of the Barthes formulation: here it is the reader who must die so that the

Author may live. (Zadie Smith, “Rereading Barthes and Nabokov.” Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays.

New York: Hamish Hamilton, 2009, 41-56.)

Smith identifies, as many of Nabokov’s academic critics do not, the way that Nabokov’s texts can instill in their readers an almost obsessive agreement with the author’s opinions. (How many writers who dislike Freud are spared Freudian readings?) Implicit in the passage Smith quotes from Nabokov is how Nabokov brings this about: he enlists his readers in the process of creation. He does this through the chess-problem structure of many of his novels: readers are asked to work out major plot points for themselves—such as Lolita’s death and Kinbote’s identity. We must also figure out that some events in the novel didn’t “really” happen even within the world of the novel, like the Gradus story in Pale Fire.

While readers of any work of fiction participate in creating a novel’s fictional world—we have to picture events and work out their ramifications—Nabokov’s readers have an unusually high degree of agency. A good reader of Nabokov, armed not just with intelligence and a dictionary, as he recommends, but with skill in working out puzzles, as he actually requires, gains “poignant artistic delight” by putting together the final pieces (Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory. New York: G. R Putnam’s Sons, 1966, 229). In the process of joining Nabokov in the act of creation, something odd happens: the reader is enlisted not just into the composition of the novel but into a kind of community of allegiance with the author. We come to share the text’s internal references and secret languages, and by the end of reading a novel like Pale Fire have been educated into the

[9]

role of the “very expert solver” of a chess problem, the ideal reader of the text (SM 228).

Readers’ involvement begins with their responsibility for helping create the physical worlds of the novels. These worlds are literally-described physical spaces—Zembla with its misty mountains, Antiterra with its woods and railway stations. Oddly, though, they do not exist independently of observation: despite Nabokov’s mad narrators’ insistence that the places they describe are “real,” these worlds only exist with the collaboration of readers and writers. Humbert’s imaginary and fraudulent “kingdom by the sea” in Lolita depends on the willingness of the reader to “imagine me—I will not exist unless you imagine me” (Vladimir Nabokov, The Annotated Lolita. Edited, with preface, introduction, and notes by Alfred Appel, Jr. New York: Vintage, 1991,129); Van’s fantasy about dying “into the finished book” of Ada requires the editorship of Ronald Oranger and the reader of the novel to complete (Vladimir Nabokov, Ada, or Ardor. New York: Vintage, 1990, 587); and Kinbote needs Shade’s help to make Zembla real in Pale Fire.

One might argue that these worlds are undercut by the flaws of their intratextual creators: Humbert enlists our imaginations because he thinks this will make us forgive his crimes, Kinbote knows on some level that Zembla does not really exist, and Van is dimly aware that his solipsism undercuts the paradisiacal claims of his memoir. But Speak, Memory makes a similar demand on readers to help in constructing the text’s world, and does so without suggesting that the world so constructed is flawed by violence, madness, or solipsism—on the contrary, it is a means of escape from the violence, madness, and solipsism of the real world. Just before the Nabokovs flee France, Nabokov’s narrative voice suddenly addresses Véra: “Sleeping in the next room were you and our child” (SM229). In this scene, the dangers of World War II in Europe recede into the distance, and Nabokov’s world becomes a tiny circle of intimacy and

[10]

family love, as Nabokov himself puts the finishing touches on a chess problem he’s been composing. The reader is at once excluded and invited in: we are not the “you” who shares a child with Nabokov, but we gain access to the intimate circle. This moment counterbalances Nabokov’s earlier claim not to care whether we understand him: “I like to fold my magic carpet, after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon another. Let visitors trip” (SM 139). The attentive reader is not a “visitor,” but “you,” part of the Nabokov family and an essential participant in his act of creation—the person who imagines Humbert not as Humbert directs but as Humbert is, and who works out that Kinbote’s name is really V. Botkin. As we engage in the puzzle solving and plot-assembly that Nabokov’s texts demand of us, we inhabit not the worlds within the novels (Zembla, the nymphets’ island) but of the worlds surrounding the novels—the worlds of artistic sympathy and tenderness the novels teach us to discover.

Nabokov’s follow-artists also turn readers into participants and insiders in their fictional worlds. These writers see Nabokov’s work as forming the core of what Salman Rushdie calls a “community of displaced persons," a community in which fiction provides communal links akin to identity markers like shared dialect or education (Nirmala Lakshman, “A Columbus of the Near-At-Hand,” in Salman Rushdie Interviews, ed. Pradyumna S. Chauhan [Westport: Greenwood, 2001], 279-290,283). For these readers and writers, books provide an alternative homeland, a world perhaps slightly more imagined than the “imagined community” of a nation but nonetheless providing commonality and mutual understanding between its participants and forging the basis of a literary lineage (see Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities. New York: Vintage, 1991).

Speak, Memory is particularly important for writers who make books the basis of affiliative identity, because Nabokov’s account of happy safety also acknowledges the limits of such

[11]

a community. Nabokov’s artistry may create alternate worlds for himself and his readers, but his real-world well-being, like everyone else’s, is still dependent on unsavory political forces beyond his artistic control—the “emetic of a bribe” must be applied to “the right rat” so he (and his Jewish wife and half-Jewish son) can leave France before the Nazis arrive (SM 229). Nabokov’s worlds, however apparently detached they may be from politics, are still urgently connected to immediate political concerns, in their composition and motivation if not in their goals.

The Iranian writer Azar Nafisi directly discusses how Nabokov can help reshape a reader’s identity. Her 2003 memoir Reading Lolita in Tehran chronicles how fiction provides an alternate “real world” for herself and her students, making book discussions in her living room on Thursday mornings into the basis for a shared identity otherwise impossible under the constraints of the Iranian regime. While she initially implies that a retreat into literature is escapist, Nafisi finally suggests that, on the contrary, fiction is more nuanced and “real” than the constrained life she leads in Tehran, even going so far as to claim that her friend “Mr. R.,” a literary “magician” who helps her understand the salutary power of fiction, is actually a character in a Nabokov story (Azar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books. New York: Random House, 2003, 34). Nabokov’s fiction both makes life under the regime comparatively livable and prepares Nafisi for eventual exile by decoupling identity from physical surroundings. On leaving Iran for the last time, Nafisi writes, “I know now that my world, like Pnin’s, will be forever a “portable world”” (Nafisi 341). Nabokov explicitly provides the model not just for escape from the dictatorship but for reconfiguring what the word “world” means: he teaches Nafisi and her students to ground their sense of self and of community in literary communion.

W. G. Sebald, a German writer who lived in England, also

[12]

takes Nabokov as a model for transcending the vicissitudes of real-world political hardship. Sebald has Nabokov make four cameo appearances in his 1993 novel/memoir The Emigrants. As both Russell Kilbourn and Leland de la Durantaye have shown, Nabokov’s appearances mark Sebald’s debt to and differences from Nabokov (Russell Kilbourn, “Kafka, Nabokov... Sebald: Intertextuality and Narratives of Redemption in Vertigo and The Emigrants''1 W. G. Sebald: History – Memory –Trauma. Ed. Scott Denham and Mark McCulloh. New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2006, 33-64; Leland dc la Durantaye, “The Facts of Fiction, or the Figure of Vladimir Nabokov in W. G. Sebald,” Comparative Literature Studies 45:4 (2008) 425-45). Sebald’s references to Speak, Memory emphasize both Nabokov’s life history of exile and his literary history of transforming memory into a “portable world.” Sebald’s characters, however, merely glimpse that world without gaining entrance, and Nabokov’s appearances point to both the allure and the danger of creating one’s own world: Sebald, like Nafisi, seems worried that the move into fiction contains elements of escapism. Unlike Nafisi, Sebald never decides that such an escape is a viable solution.

Sebald, as Adrian Curtin and Maxim Shrayer argue, identifies Nabokov’s peculiar status as a non-Jewish writer who is intimately linked to Jewish concerns, both by his wife Vera and his ethical concern with anti-Semitism and the holocaust (Adrian Curtin and Maxim D. Shrayer, “The Significance of Vladimir Nabokov in W. G. Sebald’s The Emigrants" Religion and the Arts 9:3-4 (2005): 258-83). Several recent American Jewish writers take Nabokov as a model in their own work—an apprenticeship which seems particularly indicative of Nabokov’s value to transnational writers given that Jewish writers like Philip Roth and Saul Bellow are already a part of the American literary mainstream. For writers like Myla Goldberg and Michael Chabon, Nabokov’s cultural fusions are at least as important a model for novels about American Jewry as Roth’s

[13]

Newark nostalgia; the experience Nabokov depicts of finding emotional roots in an intellectual construct seems to speak more directly to the late-twentieth-century American Jewish intellectual experience than Roth’s accounts of assimilation and struggle, especially for writers who are reluctant to connect their national identities to the state of Israel. For some contemporary Jewish writers, Nabokov becomes a model for the diasporic intellectual—someone whose roots and loyalties are both local and translocal, and who draws his readers into an idiosyncratic, geopolitically aware but personally meaningful cultural network.

Nabokov’s intellectual pluralism is, of course, intimately linked to both his ethical recognition of human subjectivity and to the artistic supernatural which haunts his novels. Myla Goldberg cites Nabokov as a model for her formal experiments in her 2005 Wickett's Remedy, a novel in which the voices of the dead appear in the margins of the text. The dead speakers render the text polyphnous and reveal how partial its narrative truth is, as their memories differ from the story told in the main body of the text. Some of these differences reveal interiorities, as when the main character’s husband remembers his own sense of shyness on first approaching her, but others quibble over the actual events narrated. These differences generally do not affect the main points of the plot—how many girls a soldier kissed on the eve of his departure for the first world war, for example; instead, they turn the text into a compendium of and meeting point for multiple viewpoints on central events. The text becomes semi-collaborative, not posing puzzles for the reader, as Nabokov’s texts do, but demanding that the reader assimilate multiple simultaneous viewpoints into a three-dimensional “world” transcending any one person’s experience. As in Goldberg’s first novel, Bee Season (2000), the supernatural component of the book dramatizes the problem of communication, whether between individuals, between living and dead, between human

[14]

and divine, or between reader and writer. Goldberg’s use of Nabokov highlights the connection between his otherworldly overtones and his interest in communion among readers.

There are many others. Salman Rushdie has two characters in The Satanic Verses (1988) discuss Zemblan, asking how to read a novel written in a “made-up lingo” and then demonstrating in the rest of the novel how fiction provides its own illuminating context to teach the reader to understand it (Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses. Dover, Delaware: The Consortium, 1988,441); Orhan Pamuk, citing Nabokov’s distance from politics as justification for the apolitical nature of his novels, writes about how Nabokov “embroils [the reader] in a game” of interpretation (Orhan Pamuk, “Cruelty, Beauty, and Time,” Other Colors. Translated by Maureen Freely. New York: Vintage, 2007, 153-9, 158). All these writers draw both on Nabokov’s love of textual puzzles and his enlistment of the reader to solve them, to help create their own fictional worlds. These worlds entail two acts of creation at once: the creation of a fictional reality (the world of the book) and of a community of readers and writers who contribute to sustaining that world.

This second creation—the creation of the metafictional community—is what sets Nabokov apart, and what gains him such devoted and sometimes obsessive readers. It is also what makes him a model for writers from such varied backgrounds: he teaches writers who stand apart from national literary traditions to find a participatory, transnational community of fellow-artists.

[15]

NOTES AND BRIEF COMMENTARIES

By Priscilla Meyer

Submissions, inEnglish, should be forwarded to PriscillaMeyer at pmeyer@wesleyan.edu. E-mail submission preferred. If using a PC, please send attachments in .doc format; if by fax send to (860) 685-3465; if by mail, to Russian Department, 215 Fisk Hall, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT 06459. All contributors must be current members of the Nabokov Society. Deadlines are April 1 and October 1 respectively for the Spring and Fall issues. Notes may be sent, anonymously, to a reader for review. If accepted for publication, the piece may undergo some slight editorial alterations. References to Nabokov’s English or Englished works should be made either to the first American (or British) edition or to the Vintage collected series. All Russian quotations must be transliterated and translated. Please observe the style (footnotes incorporated within the text, American punctuation, single space after periods, signature: name, place, etc.) used in this section.

A HUMBER SOURCE OF HUMBERT: MORE ON NABOKOV’S BICYCLES

“My poor Lolita is having a rough time. The pity is that if I had made her a boy,

or a cow, or a bicycle, philistines might never have flinched.”Nabokov to Graham Green, 1956

That infamous, unmistakenly foreign, redundantly echoing “Humbert Humbert”! The origin and meaning of his name is not clear. Nabokov’s interview with Playboy (1964) is commonly quoted (Alfred Appel, Annotated Lolita, 1991, p. 319-320) where he said: “The double rumble is, I think, very nasty, very suggestive. It is a hateful name for a hateful person. It is also

[16]

a kingly name, but I needed a royal vibration for Humbert the Fierce and Humbert the Humble. Lends itself also to a number of puns.” Among those puns we find “She has entered my world, umber and black Humberland” (a link to many underground worlds, Carroll’s Wonderland among them). Other sources of Humbert’s name point to its association with Latin umbra or French ombre (shadow): “his name partakes of these shadows and shades” (Appel, loc. cit.).

Among other possible dark sources of H. H. ’s name could be the legendary Humber the Hun, who was allegedly defeated at, and drowned in, the important English river named after him. Etymologically, “Hun” is already contained in French “Humbert,” equivalent to Old Teutonic “Humbert” (“bright Hun”). The River Humber (technically, a tidal estuary) was a major boundary in the Anglo-Saxon period; the name Northumbria means the area North of the Humber. The word humbr- may also have been a geographic term meaning “river” in pre-Celtic England. The River Humber is featured on the very first page of Robinson Crusoe (“The ship was no sooner out of the Humber than the wind began to blow and the sea to rise in a most frightful manner”). In a traditional Russian transliteration, the river is “Gumber,” just like Humbert became Gumbert in Nabokov’s translation of Lolita. The old name of the Humber River is Abus, one letter short from “abuse,” just as Humber is from Humbert. (The final “t” is anyhow mute in French, and H. H.’s father was “a Swiss citizen, of French and Austrian descent” who owned a hotel on the Riviera.)

There is an additional, previously unnoticed possible source for Humbert’s name, another Humber without a “t”—an old English bicycle model name. The Humber company was started in 1869 in Nottingham by Thomas Humber (1841 -1910). It was probably Humber who firmly established the familiar modem, so-called “diamond” frame in the 1880s. The Humber bicycle itself, to our knowledge, was never mentioned by Nabokov, but it is hidden in The Gift. Two cameo characters in this novel are

[17]

real-life American travelers, Thomas Gaskell Allen and William Lewis Sachtleben, who went around the world on these very bicycles. (For many details of their wonderful story, see Victor Fet, “An additional source for a Central Asian episode in The Gift." The Nabokovian, 2007, 57: 31-37).

The Humber bicycle name appears in the full version of Nabokov’s direct source for this story, an 1893 Russian Niva magazine article by Ivan Korostovets (“Puteshestvie dvukh velosipedistov iz Evropy v Aziyu. Korrespondentsiya ‘Nivy’ iz Pekina [Journey of two cyclists from Europe to Asia. The correspondence of ‘Niva’ from Peking].”Niva, 1893, 3:66-68). This article (p. 66) says, in Russian: “Allen and Sachtleben started their travels on Apri 13,1891, from Haidar-Pasha station (Asia Minor coast of the Bosporus) on two-wheel English “Humbertsafety” [sic; name given in English] bicycles, which weigh 40 pounds each.” Note that the bicycle model name, “Humber Safety,” was misspelled by Korostovets in English with an extra “t”!

The “Safety” term simply refers to a modern bicycle design (two equal-size wheels, etc.), much safer than that of former “Penny Farthings” (high wheelers). The first British “safety bicycles” were exported to Russia possibly starting around 1889. The Humber subsidiary company in Moscow opened in 1895 and existed until 1905 (Demaus, A.B. & Tarling, J. C. The Humber Story, Sutton Publishing Limited, 1989). “Bicycling in Russia is in its infancy,” noted John Karel, U.S. Consul General in St. Petersburg in his Consular report to the US Bureau of Foreign Commerce for May 1897. “Five bicycle factories are established.. .The two largest.. .are the Singer Cycle Company, at Warsaw, and the Humber Works, in Moscow.. .’’Newspapers (Moskovskie vedomosti, 15 July 1895) reported a bicycle race between St. Petersburg and Moscow, where “the First Prize was won on a Humber bicycle [in Russian spelling, Gumber] of the famous English Humber & Co factory.”

The 1893 article of Korostovets was clearly known to

[18]

Nabokov when he wrote The Gift in the 1930s in Berlin (Fet, loc. cit.). However, we do not know when the writer first saw this issue of Niva [Cornfield], the most popular Russian weekly magazine of his childhood. It is very possible that the story of fearless travelers (who in fact used Humber Safeties along with three other bicycle makes during their journey) was known to Nabokov since his early years from this “extinct illustrated magazine,” as he later called Niva in The Defense. Nabokov’s keen attention to bicycles, derived from his Anglophile Russian upbringing, is well known. When asked (The New York Times interview, 1969) “Reflecting on your life, what have been its truly significant moments?” he answered “Every moment, practically. Yesterday’s letter from a reader in Russia, the capture of an undescribed butterfly last year, learning to ride a bicycle in 1909” – at age 10.

Always a taxonomist, Nabokov fondly recorded early bicycle models of his childhood. Across his works, there are four different makes, two of them English (Enfield and Swift) and two, Russian (Dux and Pobeda). The biographic Drugie berega describes a Dux, with all accessories, and most lovingly mentions Nabokov’s own two English bicycles - “an old Enfield and a new Swift.” The same new Swift is found in the short autobiographic story Obida (in English translation, A Bad Day), and there is also an episodic Enfield in Glory. The Swift Cycle Company manufactured bicycles since 1869. Production of Enfields, by the Royal Enfield, started in October 1892. Two Russian bicycle makes, Dux and Pobeda (Russian for “victory”) are mentioned in a poem in The Gift, “na rame ‘Duks 'Hi ‘Pobeda ”’ (‘“Dux’ or ‘Pobeda’ on the frame”). A Dux factory was founded in Moscow in 1893 by a Russian engineer, Yuri Meller.

Autobiographic, poetic bicycle lore permeates Nabokov’s work. His early Russian poem, Velosipedist (A Cyclist) (1918) captures the simple exhilaration of bicycle ride (“rul ’ nizkii, bystrye pedali/dva serebristykh kolesa ” [“low handlebars, fast

[19]

pedals, two silvery wheels.”]) A strong bicycle theme appears in Ganin’s youth in Mary, “where is my bicycle with the low handlebars and the big gear? It seems there’s a law which says that nothing ever vanishes, that matter is indestructible; therefore the chips from my skittles and the spokes of my bicycle still exist somewhere to this day. The pity of it is that I’ll never find them again -never.” The theme continues in The Gift with one of Fyodor’s poems in Chapter I, “O, pervogo velosipeda / velikolepie, vyshina.. .”[“Oh, splendor and height of the first bicycle...”], and it resounds gloriously through autobiographic passages of Speak, Memory and Drugie berega.

In one of his best later (1938) poems, K moei iunosti [To My Youth], preserved for us in Nabokov’s own recorded reading, the author addresses himself, young: “kak ty priamo v zakat na svoem polugonochnom ’’ [“as you pedal right into sunset on your semi-racer.”] “Semi-racer” implies “low handlebars,” also mentioned elsewhere. This rare technical term is used in the Russian version of Lolita (polugonochnye avtomobili) for Quilty’s “fast cars” under “Hobbies: fast cars, photography, pets.”

From the often-discussed lemniscate tracks on the wet sand of Pale Fire, to “a long bicycle ride with seven ‘pauses’ for love-making” in Ada (Boyd, Annotations to Ada, 1.24), bicycle themes are always important for Nabokov. Adam Krug in Bend Sinister has a vision of his son David “riding a bicycle in between brilliant forsythia shrubs and thin naked birch trees down a path with a ‘no bicycles’ sign.” Two cyclists ominously enter Camera Obscura to cause the car accident central to the novel. Even the faraway postmodern Russia of Invitation to a Beheading has a weird “orthopedically enhanced bicycle.” In a bizarre biographic fact, Nabokov family bicycles were stolen in 1917 by their former valet who then was shot by the Bolsheviks for not surrendering these trophies to the new regime (!) (Drugie berega). In a typical Nabokovian pattern, on his arrival to New York in 1940, he was offered a job as a

[20]

bicycle delivery boy (Boyd, The Russian Years).

Nabokov’s childhood bicycles (ca. 1909) were fitted with pneumatic Dunlop tires invented by John Boyd Dunlop, a Scotsman, in 1888. They are mentioned both in Drugie Berega and Speak, Memory (“Along the paths of the park I would skim, following yesterday’s patterned imprint of Dunlop tires”) and also, in prose and verse in The Gift (“the Dunlop stripe left by Tanya’s bicycle”; “silence of the inflated tire” in Fyodor’s poem). Interestingly, while 1891 Humbers ridden by Allen & Sachtleben were the most advanced on the market at the time, the travelers intentionally did not use newly introduced Dunlop tires. Instead, they used an earlier, so-called “cushion” tire, which was essentially a hollow tube that had more give than the original “hard” tires but could not be punctured like pneumatics.

John Karel reports that, in 1897, the price of imported English bicycles in Russia was 160 to 250 rubles ($82 to 128.50); adjusted for inflation, these are today’s prices of $2086 to $3270. The average salary of an industrial Russian worker was about 40 rubles a month. Clearly, a child’s bicycle was then an expensive gift.

In our culture, a bicycle is still an important age-related gift from parents, an important initiation symbol, given to a child who is not yet fit to drive a car but has to learn to keep his balance entering the adult world. In Pnin (7.1), a new English bicycle (model not specified) is a gift for the narrator’s twelfth birthday (1911) in his pre-revolutionary Russian childhood.

That precious, traditional birthday gift from one’s father is usurped and corrupted by Humbert himself who gives Lolita a “doe-like and altogether charming machine” for her birthday (Lolita, 2.12). In the Russian version, the precise date is added: it was her fourteenth birthday, January 1, 1949. Exactly in a year, this bicycle, along with other belongings, will be “on her fifteenth birthday mailed.. .as an anonymous gift to a home for orphaned girls on a windy lake, on the Canadian border” (2.25).

[21]

“Her bicycle manner, I mean her approach to it, the hip movement in mounting, the grace and so on, afforded me supreme pleasure” (2.12). The make of Lolita’s “beautiful young bicycle” (2.8) remains unknown to us. At the same time, the old Humber bicycle name appears to be lodged - and repeated twice, just like “two silvery wheels” - within H. H.’s “hateful name.”

—Victor Fet, Huntington, West Virginia

—David Herlihy, Boston, Massachusetts

PALE FIRE AND DOCTOR JOHNSON

Apart from a reference to Boswell’s Life, the most conspicuous presence of Dr. Johnson in Pale Fire is a passage on his cat, Hodge, which serves as the novel’s epigraph. Another reference concerns the alleged likeness of Shade to the doctor. A useful aperture to revisit Dr. Johnson (see my “Pale Fire and the Life of Johnson”, The Nabokovian, 26, 1991) may be found in a passage of Macaulay’s review of John Croker’s edition of Boswell’s Life of Johnson which Macaulay wrote for The Edinburgh Review.

Johnson was in the habit of sifting with extreme severity the evidence for all stories which were merely odd. But when they were not only odd but miraculous, his severity relaxed. He began to be credulous precisely at the point where the most credulous people begin to be sceptical. It is curious to observe, both in his writing and in his conversation, the contrast between the disdainful manner in which he rejects unauthenticated anecdotes, even when they are consistent with the general laws of nature, and the respectful manner in which he mentions the wildest

[22]

stories relating to the invisible world. A man who told him of a water-spout or a meteoric stone generally had the lie direct given him for his pains: A man who told him of a prediction or a dream wonderfully accomplished was sure of a courteous hearing. ...

[H]e related with a grave face how old Mr. Cave of St. John’s Gate saw a ghost, and how this ghost was something of a'shadowy being. He went himself on a ghost-hunt to Cock-Lane, and was angry with John Wesley for not following up another scent of the same kind with proper spirit and perseverance. (Thomas Babington Macaulay, Sept., 1831, Repr. in Critical and Historical Essays. Leipzig: Tauchnitz, 1850, 5 vols., vol. 1, 386-7)

The affair of the Cock Lane ghost was a most sensational event that engrossed London in 1762. This ghost was of the poltergeist-type, exactly like Hazel’s “domestic ghost” (164), and communicated by rapping and scratching, answering questions with knocks, one for “yes” and two for a negative, much like the “Spirit” in “Pale Fire,” lines 649-650 (though here the spirit refrains from answering the questions posed). Although Horace Walpole thought that the whole place reeked of fraud, Johnson joined a committee of inquiry, and wrote an account on behalf of the deputation in which he writes that “|t]he spirit was solemnly required to perform ...” (Margaret Lane, Samuel Johnson and His World. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1975, 148-9. Johnson’s report is included in James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D., 1791, London: Everyman’s Library, 1952, 2 vols., vol. 1, 252-3). Of course, Walpole’s suspicions proved to be opportune, and the whole business was declared a counterfeit in Johnson’s report. Johnson was nonetheless a great believer in ghosts: “It is wonderful that five thousand years have now elapsed since the creations of the world, and still it is undecided whether or not there has ever been an instance of the spirit of any person

[23]

appearing after death. All argument is against it; but all belief is for it” (Boswell, vol. 2, 167).

Johnson was not only inclined to recognize ghosts, but to embrace other kinds of paranormal occurrences as well. “[H]e was willing,” writes Boswell, “to inquire into the truth of any relation of supernatural agency, a general belief of which has prevailed in all nations and ages” (Boswell, vol. 1, 252). Nabokov shared this interest with Johnson as well Johnson’s dualistic attitude towards supernatural phenomena. Tuuli-Ann Ristkok, who has traced many of the sources of the occult events Nabokov refers to in “The Vane Sisters,” writes that “Nabokov’s remarkable familiarity with such details can only have been acquired through extensive reading in these volumes of reports and investigations, ...” and that “the question is whether Nabokov may be hinting that despite the examples of fraud, he accepts at least to some degree the possibility that occult and psychic phenomena may be ‘veridical’” (“Nabokov’s ‘Vane Sisters’—Once in a Thousand Years of Fiction,” University of Windsor Review, vol. 11, 1976. 27-49, 41). Johnson also believed in miracles, the argument being that God may suspend the laws of nature “in order to establish a system highly advantageous to mankind” (Boswell, vol. 1, 275). Johnson’s fear of death was caused by the complete unpredictability of the hereafter, a mystery (although Johnson was far more acquiescent in its insolvability than Nabokov) which frequently exercised his mind. “Ah! We must wait till we are in another state of being, to have many things explained to us,” said Johnson, much in the same vein as Fyodor’s expression, “’You will understand when you are big "(Gift 342).

Macaulay proceeds with the discussion of another incident, about a young boy who suddenly sensed and declared that his father had died, which proved to be true, though the boy was in France and his father in Ireland, a distance that at that time could not be covered in less than a fortnight (Samuel

[24]

Johnson, Lives of the English Poets, 1779-1781, London: Everyman’s Library, 1954, 2 vols., vol. 1, 134). As there were several witnesses, Johnson taxes his readers with the choice between “reason or testimony,” but it is clear that Johnson’s willingness to believe this “miracle” is hardly curtailed by his own dictum that this would be irrational.

Although the Cock Lane poltergeist was not quite a genuine ghost, Johnson thought that he had conclusive evidence of at least a few supernatural occurrences. There is the case of Lord Lyttelton’s prophecy, the prediction of the time of his own death which Johnson “heard with [his] own ears from [Lord Lyttelton’s] uncle” (Boswell, vol. 2, 525). According to Walter Scott, Lord Lyttelton had taken poison and therefore could predict his death trustworthily (Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft. London: George Routledge, 1885, 289). Then there is that auditory mystery which is so very similar to what happened with Kinbote. Johnson, writes Boswell, “mentioned a thing as not infrequent, of which I had never heard before, —being called that is, hearing one’s name pronounced by the voice of a known person at a great distance, far beyond the possibility of being reached by any sound uttered by human organs” (Boswell, vol. 2, 381). Next Johnson tells about an acquaintance “on whose veracity [he] can depend,” who heard, while walking in the woods somewhere in Scotland, the voice of his brother who had gone to America, “and the next packet brought accounts of that brother’s death.” And Boswell proceeds by relating that “Dr. Johnson said, that one day at Oxford, as he was turning the key of his chamber, he heard his mother distinctly call - Sam. She was then at Lichfield; but nothing ensued.” This conversation took place on a Sunday (April 15, 1781) “after solemn worship in St. Paul’s church” (Boswell, 2, 379). The likeness to what befell Kinbote, whose fear of Hell is as strong as Dr. Johnson’s, as Kinbote ponders dejectedly that “these is a chance yet of my not being excluded from Heaven, and that salvation may be granted to me despite

[25]

the frozen mud and horror in my heart”(258), is striking. On a Sunday (July 19, 1959), after having prayed in two different churches, Kinbote returns home; what happens next is best told by quoting Kinbote verbatim:

As I was ascending with bowed head the gravel path to my poor rented house,

I heard with absolute distinction, as if he were standing at my shoulder and speaking

loudly, as to a slightly deaf man, Shade’s voice say: ‘Come tonight, Charlie.’ I looked

around me in awe and wonder: I was quite alone. I at once telephoned, The Shades

were out, said the cheeky ancillula.... I retelephoned two hours later .... and asked him

[Shade] as calmly as possible what he had been doing around noon when I had heard

him like a big bird in my garden. He could not quite remember, said wait a minute, he had

been playing golf with Paul.... or at least watching Paul play with another colleague. (258-9)

The coincidences with the experience of Johnson are evident and might explain the use (as in Johnson’s case) of a more familiar form of Kinbote’s given name (“Charlie” rather than Charles). But contrary to Johnson’s case, who could tell that “nothing ensued,” Shade dies two days after this incident.

Macaulay also points to Johnson’s acceptance of “the claim of the Highland seers.” This claim, the possession of second sight, was a frequent topic of discussion and enquiry during the trip Johnson and Boswell made to the Highlands and the island of Skye. They both wrote a record of their travels, A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775) by Johnson, and The Journal of a tour to the Hebrides (1786) by Boswell (published in one volume by Penguin Books, 1984). Johnson’s discussion of second sight amounts to a small learned treatise, well documented by the sources available to him (Thomas Jemielity, “Samuel Johnson, the Second Sight, and his Sources,” Studies in English Literature

[26]

1500-1900, vol.14, 3, 1974, 403-420). He defined second sight as “an impression made either by the mind upon the eye, or by the eye upon the mind, by which things distant or future are perceived, and seen as if they were present” (110). It was regarded as a phenomenon only to be found in the Scottish Highlands, and most common in Skye. That the Highland seers “often see death,” Johnson writes, “is to be expected: because death is an event frequent and important”(lll). In a note appended to The Lady of the Lake, Walter Scott writes that “in despite of evidence which neither Bacon, Boyle, nor Johnson were able to resist,” this visionary faculty “seems to be now universally abandoned to the use of poetry”(The Poetical Works of Sir Walter Scott, Oxford Complete Edition, 1904,279. This edition was reprinted many times at least until the nineteen-seventies).

The Lady of the Lake includes two Highland seers, Brian, the Hermit, and Allan, the Minstrel, and its Canto IV is titled “The Prophecy” in reference to the vision Brian sees after he has “unfurled,/ the curtain of the future world” (IV, VI, 1. 116-17). Shade, whose Canto IV shelters a prophecy or premonition as well, had two visions foreshadowing future events. In his youth, at the age of eleven, while playing with a toy wheelbarrow pushed by a boy, he had a fainting attack and felt distributed through space and time, which scene forecasts his actual death. Another vision Shade had on 17 October, 1958 anticipated Mrs. Z’s experience. This vision also was preceded by a fainting spell. A similar sequence of fits and visions can be observed among Highland seers. Boswell tells about a young Mr. M’Kinnon (whom he and Johnson met in Skye): “Young Mr. M’Kinnon mentioned one M’Kenzie, who is still alive, who had often fainted in his presence, and when he recovered, mentioned visions which had been presented to him.” One such vision was about a funeral, “and three weeks afterwards he saw what M’Kenzie had predicted” (249). And in Wales Scott’s A Legend of Montrose,

[27]

the seer Allan M’Aulay (or MacAulay) suffers from severe fainting attacks before making his prophesies: “straining his eyes until they almost started from their sockets, he fell with a convulsive shudder into the arms of Donald and his brother, who, knowing the nature of his fits, had come near to prevent his fall” (references to the Waverley Novels are made to the Border Edition, edited by Andrew Lang, 24 vols., London: Macmillan & Co., 1900; vol. VII, 71). As has been mentioned, the visions of these seers often concern impending death. In a lengthy note on second sight, Andrew Lang writes how seers call the persons whose approaching death they have perceived, “fey” (vol. VII, 307-310). This archaic word is also used by Shade in his poem, “Pale Fire,” line 968. The 1901 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (vol. IV) shows that an antique form of this word can be found in Beowulf (in line 1568, translated as “death-doomed” by Michael Alexander, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1973, 100; see also line 2141, p. 118) as well as in Langland’s Piers the Ploughman. Apart from these exceptions, its use seems to be limited to Scottish authors. In the Everyman’s Library edition of R.L. Stevenson’s Weir of Hermiston (1896, London, New York, 1974) the word is glossed as “unlike oneself, ‘strange’ (as persons are observed to be in premonition of death)” (294, see also 254). Walter Scott uses the word “fey” in several of his novels, always meaning as being “predestined to speedy death,” an expectation based on some kind of foreknowledge (and not on natural explanation such as ill health) (The Pirate, vol. XIII, 70, see also The Heart of Mid-Lothian, vol. VI, 40 and 45 and The Fait Maid of Perth, vol. XXI, 297-98). It seems that Shade used this word in very much the same way, as may be concluded from his lines 967-970:

Maybe my sensual love for the consonne

D ’appui. Echo’s fey child, is based upon

A feeling of fantastically planned,

[28]

Richly rhymed life. ...

Clearly Shade senses that his versification corresponds with the turnings his life might take. Or as Shade has it in line 974: his “private universe scans right.” What role does this “consonne d’appui” play in Shade’s life? As Brian Boyd has explained, a consonne d’appui denotes “a repeated consonant preceding the vowels normally taken as the beginning of the rhyme” (Nabokov s Pale Fire: The Magic of Artistic Discovery, Princeton: PUP, 1999, 285). “[I]f the next line after line 999,” Boyd writes, “reads ‘I was the shadow of the waxwing slain’ it will indeed have that consonne d’appui (the 1 of ‘lane’ and ‘slain’).. .”(218). Boyd’s presumption seems well-founded, as may be concluded from Shade’s interpolated phrase: “Echo’s fey child”; the echo of the rhyming pattern resounds in a word suggestive of a fey being which repeats the supporting consonant. As “fey” signifies the foreshadowing of death, the last word of line 1000 must be “slain.” (The only monosyllabic alternatives, “plain” and “plane,” lack the import the adjective “fey” requires.) Doubtless, the final line of “Pale Fire” is the same as its initial line. Shade has predicted his own death by his versification. At the same time he has foreseen his afterlife, as he will live on as line 4 intimates. Lines 977 and 978 confirm this:

I’m reasonably sure that we survive

And that my darling somewhere is alive

“Survive” means to live on after an event, which makes death more likely than remaining alive. What was the life-threatening incident that Shade anticipated? Certainly not the setting of the alarm clock or the putting back of his volume of poems on its shelf, as Shade so placidly observes in lines 983-84. And how can his daughter be alive, given that readers still feel overwhelmed by her death as related in Canto II? It is obvious

[29]

that Shade is referring to an afterlife which will re-unite him and his wife and with their daughter. And it is remarkable how different the tone of Canto IV is, especially its second half, compared with the worrying strain which marks Canto II. The afterlife, in Canto II still a “foul” and “inadmissible abyss,” is welcomed serenely in Canto IV by gracious modulations of thought. It might be that this confident tone, which assures the reader that Shade has finally seen the right answer to the question which has tormented him “all [his] twisted life,” makes the choice of the novel’s epigraph understandable.

The epigraph that Nabokov borrowed from Boswell’s Life is about a madman who kills cats. Pale Fire ends with the murder of Shade by a madman. Boswell tells how Johnson, thinking about the fate of his favorite cat, Hodge, “in a sort of kindly reverie” says that “Hodge shall not be shot.” In his wording Johnson uses four denials. He must have been quite convinced that Hodge would survive. Johnson’s rumination is untroubled; his “kindly reverie” shows that he is not worried at all and even finds some pleasure in his musings, as if he had some sort of prescience. Are readers supposed to compare this “reverie” with the serenity of Shade’s thoughts while he was composing the last three stanzas of his poem, knowing that he could be reasonably sure he would survive?

Addendum. It might be observed that the present reading of some of the lines of Canto IV are rather dependent on some familiarity with Scottish letters and lore. Because not everyone may rank Walter Scott as high as a novelist of his age as I rank Nabokov among the novelists of his own century (although Alexander Dolinin, who published a book on Scott’s novels, might sympathize with this position), it could be argued that the views expressed here are due to a mere coincidence. This objection, however, seems difficult to defend. Dictionaries present “fey” as a Scottish word. Next, the Scottish connections in Pale Fire are rather conspicuous. Mary McCarthy’s discovery (about half a century ago) that

[30]

Hazel Shade’s name is taken from The Lady of the Lake has often been repeated. And that the tutor of King Charles when young, was a Scotsman who taught princesses to enjoy Walter Scott’s Lord Ronald’s Coronach is as robust a truth as Zembla can provide. No less real is Aunt Maud’s Skye Terrier, or the reference to the coronation chair of a Scottish king. The name of the Shade family’s oculist, Jim McVey, has a Scottish ring as does the name of the place where Hazel gets off the bus, Lochanhead, to drown herself in the lake near Lochan Neck. Lochanhead resembles most closely the Lochearnhead out of the booklet by Angus M’Diarmid, A Description of the Beauties of Edinample and Locheamhead, from which Kinbote quotes the phrase “incoherent transactions.” It is, to conclude this postscript, quite remarkable that the settings of the Lady of the Lake, of Lord Ronald’s Coronach and of M’Diarmid’s account are all located in a small area, between Loch Katrine and Loch Earn, the distance between these lakes being only about 20 kilometers.

– Gerard de Vries, Voorschoten, Netherlands

NABOKOV—CHUKOVSKY CONTROVERSY: THE OSCAR WILDE EPISODE

In his diary entry for January 13, 1961, Kornei Chukovsky (1882-1969), a journalist, literary critic, and

children’s writer, praises Nabokov’s Pnin: “I am now reading Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin, a great book to the glory of the Russian righteous man thrown into the American university life. The book is poetic, clever—about the absentmindedness, un-adultness, and amusingness, and soul’s greatness of the Russian semi-professor Timofei Pnin. The book is

[31]

saturated with sarcasm—and with love.” (“Teper' chitaiu knigu Vladimir’a Nabokov’a ‘Pnin,’ velikuiu knigu, vo

slavu russkogo pravednika, broshennogo v amerikanskuiu universitetskuiu zhizn'. Kniga poetichnaia, umnaia—o rasseiannosti, nevzroslosti i zabavnosti i dushevnom velichii russkogo poluprofessora Timofeia Pnina. Kniga nasyshchena sarkazmom—i liubov'iu”) (Kornei Chukovsky, Dnevnik [1930—1969], Moscow: Soveremennyi pisatel', 1994, 297). Chukovsky goes on to delineate the novel’s main plotline and to point at the unreliability of its narrator: “In this novel, the author shares his recollections with the readers about one Russian man whom he used to encounter in Petrograd, Paris, and America. This man does not have a very high opinion of the veracity of his biographer. When the latter began a conversation in his presence about a certain Ludmila, Pnin shouted to his interlocutors: ‘Don’t believe a word he says... It’s all lies... He is a dreadful inventor.’” (“V etom romane avtor delitsia s chitateliami svoimi vospominaniiami ob odnom

russkom cheloveke, kotorogo on vstrechal v Petrograde, v Parizhe, v Amerike. Etot chelovek ne ochen'-to vysokogo mneniia o pravdivosti svoego biografa. Kogda tot zavel v ego prisutstvii razgovor o kakoi-to Liudmile, Pnin gromko kriknul ego sobesednikam: ‘Ne ver'te ni odnomu ego slovu. Vse eto vraki... On uzhasnyi vydumshchik!’ ‘Don’t believe a word he says... He makes up every thing [sic]... He is a dreadful inventor’”) (ibid. 297-98). Deliberately confusing V. N., the novel’s narrator and character, and his authorial namesake, Chukovsky, then, asserts: “Regrettably, I learned this from my own experience. Quoting his father, Vlad.<imir> Dmitrievich Nabokov, the novelist recounts in his memoirs that allegedly at the time when I appeared at Buckingham Palace before George V, I allegedly turned to him with a question about Oscar Wilde. Nonsense! The King read out his text and V. D. Nabokov—-his. One was not supposed to talk to the King. It is all a tall tale. He slanders his father...” (“V etom, k

[32]

sozhaleniiu, ia ubedilsia na sobstvennom opyte. So slov svoego ottsa Vlad.<imira> Dmitrievicha Nabokova romanist rasskazyvaet v svoikh memuarakh, budto v to vremia, kogda ia predstal v Bukingemskom dvortse pered ochami Georga V, ia budto by obratilsia k nemu s voprosom ob Oskare Uail' de. Vzdor! Korol' prochital nam po bumazhke svoi tekst i VI. D. Nabokov—svoi. Razgovarivat's korolem ne polagalos'. Vse eto anekdot. On kleveshchet na ottsa...” (ibid. 298).

In this diary entry, Chukovsky refers to the passage from Nabokov’s memoirs that he could read at the time both in English (Conclusive Evidence, 1951) and in Russian (Drugie berega, 1954). The passage in question reads: “There had been an official banquet presided over by Sir Edward Grey, and a funny interview with George V whom the critic Chukovski, the enfant terrible of the group, insisted on asking if he liked the works of Oscar Wilde—‘dze ooarks of Ooald.’ The king, who was baffled by his interrogator’s accent and who, anyway, had never been a voracious reader, neatly countered by inquiring how his guests liked the London fog (later Chukovski used to cite this triumphantly as an example of British cant—tabooing a writer because of his morals)” (CE 187; for the Russian text, see Ssoch, 5: 299-300).

How, then, to reconcile these two contradictory accounts, one by Nabokov, which he heard from his fatherin 1916 and related some thirty-five to forty years later, and Chukovsky’s repudiation of it in 1961? Perhaps the following account by another member of the Russian delegation, Efim Aleksandrovich Egorov (1861-1935), a journalist and the foreign editor of the St. Petersburg daily, The New Time (Novoe Vremia), written hot on the heels of the events, will help to clarify the matter. This is how Egorov describes the audience with King George V: “The King entered. He was in the same modest costume as his modest Russian visitors. The Ambassador presented us one after the other; the King shook our hands with truly British energy, and said a pleasant word

[33]

to each. He then begged us to come closer, and addressed us in a speech which we afterwards reconstructed from memory and transmitted by telegraph to Petrograd. [...] on this occasion it was not an Englishman who spoke to us; it was England herself. The speech was simple, clear, naturally developed, without the slightest affectation or compulsion. [...] On pronouncing the final words of his speech, the King turned to one of those present and asked, ‘Have you all understood me?’ We hastened to reply, ‘All,’ although in fact some of us were not very strong in the language of our island Allies and understood rather the harmony of the words than their meaning. After this little misunderstanding the King turned to Nabokov, who was standing closest of all to him in the field uniform of a subaltern, with the question, ‘Were we visiting England for the first time.’ I did not hear how Nabokov answered, but he closed his reply with an expression of gratitude for the gracious reception and gracious words addressed by the King to the Russian journalists. The King then took leave of us, again shaking our hands” (The Times Russian Supplement, April 29, 1916, 2). Egorov’s account, although not reporting any specific word exchange between George V and Chukovsky, nonetheless refutes the latter’s notion that “one was not supposed to talk to the King.” Furthermore, it demonstrates that the King shook hands and spoke, albeit briefly, with each member of the Russian delegation. It is quite possible, therefore, that, being “the enfant terrible of the group,” Chukovsky asked the King his Oscar Wilde question precisely at that time. While Chukovsky calls Nabokov “a dreadful inventor,” purposely mixing up V.N., the narrator of Pnin, with its author to prove his point, Egorov’s account calls the veracity of Chukovsky’s rebuttal into question. The last phrase of the diary entry betrays Chukovsky’s anger. It is highly peculiar that Chukovsky, a renowned man of letters, an authority on the Russian language, the author of Alive as Life (Zhivoi kak zhizn' ), employs the

[34]

excessive locution “slanders his father” (“kleveshchet na ottsa”) when attempting to refute Nabokov’s account whereas “distorts his father’s words” (“iskazhaet slova ottsa”) would have been sufficient and more suitable. Earlier in the same passage, Chukovsky’s embarrassment can be discerned in his trying very hard to contest Nabokov’s account by awkwardly using the almost identical locutions (“budto” and “budto by”) within one sentence.

Further, Nabokov evidently aroused Chukovsky’s rancor by ridiculing his poor English pronunciation. Nabokov also undoubtedly stirred Chukovsky’s ire when presenting him in an unfavorable light: drawing groundless conclusions based on sheer miscommunication and wishful thinking. Curiously, in doing so, Chukovsky emulated an incident that occurred to Alexander Herzen, one of his literary idols (see Chukovsky, Dnevnik [1930—1969], 240 and 363), also in London, more than fifty years earlier. As Nabokov describes it in The Gift, Herzen “had confused the sounds of two English words ‘beggar’ and ‘bugger’ and from this had made a brilliant deduction concerning the English respect for wealth” (Gift 201).

—Gavriel Shapiro, Ithaca, New York

ANNOTATIONS TO ADA'S SCRABBLE GAME

According to Ada, the heroine of Nabokov’s eponymous novel, Van’s and Ada’s younger half-sister Lucette even as a child of eight could remember a lot of “bagatelles, little ‘ turrets ’ and little ‘barrels,’ biryul’ki proshlago. She was, cette Lucette, like the girl in Ah, cette Line (a popular novel), a macédoine of

intuition, stupidity, naïveté and cunning’” (1.24).

[35]

As pointed out by Boyd (“Annotations to Ada," 152.10-11, The Nabokovian 54), the popular novel’s title is a pun on acetylene, colorless ether-smelling gas widely used as an illuminant until it was ousted by electric light. Acetylene is mentioned in the first stanza of Wilgelm Zorgenfrey’s poem Nad Nevoy (“Over the Neva,” 1920):

Pozdney noch 'yu nad Nevoy,

Vpolose storozhevoy,

Vzvyla zlobnaya sirena,

Vspykhnul snop atsetilena.

Late night over the Neva.

There, where they are keeping watch,

A siren sends up its vicious howl,

Acetylene flares a pillar of fire.

Apart from acetylene, Zorgenfrey (a minor poet, 1882-1938, who perished in the Soviet purges of the 1930s, the dedicatee of Blok’s famous Don Juan poem, Shagi komandora, “The Commander’s Footsteps,” 1910-12) famously mentions in his poem another fuel, kerosene:

– Ya segodnya, grazhdanin,

Plokho spal:

Dushu ya na kerosin

Obmenyal.

“Citizen!

I slept badly last night:

For kerosene

I’ve exchanged my soul.”

Kerosin, for which the poor inhabitant of the devastatedSt. Petersburg of the years of War Communism exchanged his

[36]

soul, is the word that Ada’s letters form at the beginning of one of the Flavita (Russian scrabble) games played by Van, Ada and Lucette at Ardis one August evening in 1884. Even more mysteriously, when Ada was collecting her seven letters, she casually says: “I would much prefer the Benten lamp here but it is out of kerosin" (1.36).

In my article in Russian, “Will Grandma Get the Xmas Card, or Why did Ada's Baronial Barn Burn?” (http://www.libraries.psu.edu/nabokov/sklyarenko6.doc) I suggest that kerosene is absent in the “Benten” and possibly in all the other kerosene lamps in Ardis Hall because it was used by Ada (who needed the house to be empty for several hours which she would spend in intimacy with Van) and her accomplices to set the bam on fire. I compare the Burning Bam scene in Ada (1.19) to the fire in Ilf and Petrov’s The Golden Calf (1931) that destroys the so- called Voron’ya slobodka (“Raven’s Nest”). The latter is set on fire by its restless inhabitants, who are afraid that, unless they do it themselves (having insured their property beforehand), their house will sooner or later burn down because of “no one’s grandmother” who doesn’t trust electricity and uses a perilous kerosene lamp in her entresol lodgings.

Kerosene is used as a fuel not only in lamps, but also in various stoves, including the primus. The primus stove is mentioned, along with “white kerosene,” in Mandelshtam’s poem My s toboy na kukhne posidim (“You and I shall sit for a while in the kitchen...” 1931) and in Ilf and Petrov’s “The Twelve Chairs” (1928). A young couple, the inhabitants of “the Brother Berthold Schwarz hostel” (as Ostap Bender, the novel’s hero, jokingly renames the Semashko hostel for chemistry students in Moscow after the Franciscan monk and alchemist believed to be the first European to discover gunpowder), turn on their primus every time when they want to drown the sounds of their frequent love-makings. But it doesn’t help much: the neighbors can hear everything through the thin veneer partitions and it is only the Zverevs themselves who, deafened by their constantly

[37]

working apparatus, blissfully hear nothing (chapter XVI: “The Brother Berthold Schwarz hostel”).

Van calls the bedchambers and adjacent accommodations he is assigned during his stay at Ardis “more than modest” (1.6), but they must be luxurious compared to the tiny hostel room, resembling one of those pencil-box compartments, in which Bender and Vorob’yaninov have to dwell in Moscow. The squalid “Brother Berthold Schwarz hostel” and the majestic Ardis Hall mansion have only one thing in common: the spiral staircase that, in the Moscow building, leads to Panteley Ivanpulo’s room in the attic story (where Bender and his companion eventually put up) and, in Ardis Hall, to the third floor library where Van and Ada make love for the first time.

They do it on the divan near the window from which they can see the glow of the distant fire. On the evening preceding the Night of the Burning Bam the three young Veens play Flavita (1.36) and Lucette’s letters form the amusing VANIADA (the central i in it is the Russian counterpart of “and”). From these she extracts divan, a word that also exists in Russian, with exactly the same meaning. It seems to me there is a correspondence between this piece of furniture, the Vaniada divan (on which Lucette says she too would like to sit but is not allowed space), and the twelve Gambs chairs in Ilf and Petrov’s novel, as well as between the diamonds that Mme Petukhov, Vorob’yaninov’s late mother-in-law, had concealed in the upholstery of one of the dozen of chairs and the diamonds (that turn out to be false) in the story written by Mile Larivière, Lucette’s governess (1.13).

Mile Larivière makes a debut reading of herLo Rivière de Diamants, the Antiterran version of La Parure (1884) by Guy de Maupassant (the writer, who, according to Vivian Darkbloom, the author of “Notes to Ada'' doesn’t exist on Antiterra, the twin planet of Earth, on which Nabokov’s novel is set), at the picnic on Ada’s twelfth birthday. On the way back from the picnic site, Van, sitting in the caleche beside Mile Larivière, has to hold Ada in his lap. It is Van’s and Ada’s first physical

[38]

contact (four years later, returning from the same picnic site, Van, now sitting beside Ada, holds Lucette in his lap: 1.39). Now, in The Twelve Chairs (chapter XI: “The ‘Mirror of Life’ Alphabet”) Ostap Bender says to Varfolomey Korobeynikov, the keeper of the Stargorod archives: blizhe k telu [“closer to the body, a pun on blizhe k delu, “get/come to the point”], as Maupassant [my emphasis] says.” It is from old Varfolomeich (cf. Varfolomeevskaya noch ’, Russian for “St. Bartholomew’s night,” the massacre of the Huguenots in Paris) that Bender manages to receive orders for the furniture that had belonged to Vorob’yaninov, the former marshal of nobility in Stargorod, before it was nationalized by the new regime.

From these orders Bender and Vorob’yaninov learn that one of the twelve chairs they are hunting for belongs now to grazhdanin (citizen) Gritsatsuev, “a disabled soldier of the Imperialist War.” They pay him a visit but, instead meet his widow, Mme Gritsatsuev (“the ardent woman, a poet’s dream” or “the diamond widow,” as Ostap calls her), whom Bender decides to marry in order to search her chair (which is also French for “flesh”). Bender leaves her (on the first night of his married life) and, when her disemboweled chair proves empty, sets off with Vorob’yaninov to Moscow. The spouses meet once again there, in the editorial office of the Stanok (“Machine-Tool”) newspaper, and this time Bender has to lock his wife in a staircase landing in order to escape from her (chapter XXVIII: “The Pullet and her Pacific Cock”).

The name of Bender’s poor jilted wife is echoed in Ada, in the name of an (apparently, luxurious) hotel. (And, vice versa, Mile Larivière’s pen-name, Guillaume de Monpamasse [sic!], hints at Maupassant but, Montparnasse being a district in Paris, also reminds one of the cheap Stargorod hotel, in which Bender and Vorob’yaninov, as well as their rival, Father Fyodor, put up: Sorbonne.) Baron Klim Avidov, one of Marina

Durmanova’s former lovers who gave her children the Flavita set (1.36), is said to have knocked down an English tourist, a

[39]

certain Walter C. Keyway, Esq., for his jocular remark that it was clever “to drop the Erst letter of one’s name in order to use it as a particule, at the Gritz, in Venezia Rossa” (see also my essay in Russian “Fisted Good, the Kulak Property, Kulaks Robbed of their Property: How Nabokov Unclenches Evil’s Fists in Ada" at http://www.topos.ru/articles/0908/03_03.shtml). Several anagrams would be appropriate here:

BARON KLIM AVIDOV = VIVIAN DARKBLOOM = VLADIMIR NABOKOV

BENTEN + TAM -TAM + OH = BENTHAM + TEMNOTA

(Benten is a Japanese goddess of the sea and the name of the indigenous part of Yokohama mentioned in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days (1873), the novel alluded to in Ada's first chapter; tam-tam is a gong mentioned in the same “Japanese” chapter of Jules Verne’s novel; Bentham is Jeremy Bentham, 1748-1832, English jurist and philosopher, who is mentioned in Eugene Onegin: Canto One, XLII, 5-6; temnota is Russian for “darkness” and “ignorance”; cf. Kim Beauharnais, the kitchen boy and photographer at Ardis, who must have helped Ada to set the bam on fire and who, many years later, is blinded, or, in other words, “plunged into darkness,” by Van for having spied on him and Ada: 2.11)

IVANOPULO + STANOK + D = DIVAN + POLUSTANOK + O (D is a letter of the Latin alphabet that W. C. Keyway believes was dropped by Baron Klim Avidov to be used as a nobility particle before the surname; cf. “the ‘D’ also stood for Duke, his [Gran D. du Mont’s, one of Marina’s lovers, in whose company little Ada and Lucette traveled in Europe] mother’s maiden name”: 1.24; in the old Russian alphabet, D’s alphabetic counterpart was called dobro, “good” as a noun; polustanok is Russian for “whistle stop”; cf. Torfyanka and Volosyanka, two whistle stops near Ardis: 1.41)

[40]

PARIS = PARSI = PSARI = SPIRAL – L (Paris is the city in and capital of France; on Antiterra is also known as Lute, apparently, short of Lutetia, the city’s ancient name; the legendary Trojan prince, a character in Homer’s Iliad', a character in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, 1599; Parsi is an Indian Zoroastrian descended from Persian Zoroastrians who went to India in the 7Ih and 8th centuries to escape Muslim persecutions; Aouda, the character in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, is a Parsi woman whom the novel’s hero, Phileas Fogg, saves in India and marries in London; cf. Persitskiy, a character in Ilf and Petrov’s The Twelve Chairs, a reporter working for the Stanok newspaper, whose name means “Persian”; psari is Russian for “persons in charge of hounds”; cf. Pushkin’s lines from the beginning of Count Nulin, 1825: Psarivokhotnich’ikh uborakh / Chut ’ svet uzh na konyakh sidyat, “At daybreak people in charge of hounds in huntsmen clothes are already on horseback”; spiral is a helix; cf. Nabokov: “The spiral is a spiritualized circle”; cf. the spiral staircase in Ardis Hall and in the Moscow “Berthold Schwarz hostel”; L is a letter of the Latin alphabet; Lucette’s initial with which she remains in a Flavita game after composing innocent rotik, “little mouth,” of her six letters: L, I, K, R, O, T: 2.5; cf. “poor Mile L.” as Ada refers to Mile Larivière: 1.3; cf. the L disaster that caused, among other things, the banning of electricity on Antiterra: 1.3)

LUCETTE + FIRE = LUCIFER + TETE = LUTE + FREE + CITADEL – ADEL (Lucifer is a rebellious archangel, identified with Satan, who fell from heaven; a character in Milton’s Paradise Lost, 1667; the planet Venus when appearing as the morning star; in Ada, Van calls fireflies lucifers: 1.12; tête is French for “head;” cf. Pushkin: Mais je n 'ai point tourné de tête, “I didn’t turn her head,” the third line of Pushkin’s four- line French poem "J’ai possédé maitresse honêtte..." 1821; cf. “[Mile Larivière] told him [Van] to refrain from turning

[41]

Lucette’s head by making of her a fairy-tale damsel in distress:” 1.23; Lute is the Antiterran alternative name of Paris; free is “enjoying personal rights or liberty, as a person who is not in slavery;” cf. the question Van asks himself when he wakes up on the morning following the Night of the Burning Barn: “Are we really free?”: 1.20; citadel is a fortress that commands a city; any strongly fortified place, stronghold; Adel is German for “nobility”)

Mile Larivière asks Van to refrain from turning her little charge’s head by making of her a fairy-tale damsel in distress after Lucette complains that Van and Ada, while playing, tied her to a tree with a skipping rope. They wanted to get rid of their half-sister’s importunate presence for a few minutes in order to make love in a nearby grove. When they return to the captive, they find that she has almost managed to disentangle herself. But several days later Ada informs Van that Lucette confessed, in fact, Ada made her confess, that it was the other way round: “when they returned to the damsel in distress, she was in all haste, not freeing herself, but actually trying to tie herself up again after breaking loose and spying on them through the larches” (1.24).

Van and Ada are afraid that Lucette can tell her governess, who would pass it on to Marina, the three children’s mother (officially, though, Van is Ada’s and Lucette’s first cousin), about their romance, which would put an end to it. But they fear in vain: poor Lucette does not give away their secret (“I can’t speak to Belle [Lucette’s name for her governess] about dirty things,” she says when Ada accuses her of having a dirty mind: 1.40). All the same, Van and Ada should have heeded Ida Larivière’s warning and not involve their little half-sister in their affair. It is, in part, because she remembers the past’s baubles, biryul'ki proshlogo, too vividly (“One remembers, Van, those little things much more clearly than the big fatal ones,” she once says to Van: 2.5) that Lucette, who also fell in

[42]

love with Van, eventually commits suicide (3.5).

The Russian word biryul'ka that can be translated as “bauble” or ‘’’trifle” literally means “spillikin,” jackstraw.” It is in this meaning that Mandelshtam (whose work is as important in Ada as Ilf and Petrov’s) uses it in one of his Vos 'mistishiya (“The Eight-Line Poems,” 1933):

I tam, gde stsepilis ’ biryul’ki,

Rebyonok molchan’e khranit -

Bol ’shaya vselennaya v lyul ’ke

U malen ’koy vechnosti spit.

And there, where the spillikins are coupled,

The child keeps silent.

In little eternity’s cradle

The big universe is asleep.

Like Mandelstam’s spillikins, or his metaphors, the coupled allusions in Ada are very difficult to disentangle. It seems to me that Ah, cette Line, a popular novel’s Franco-English title, hints not only at acetylene, but also at a certain Russian poetic line. Can we ever establish it? A stuffed owl and a “motor landaulet” mentioned in the same chapter of Ada (1.24), as well as Don Juan s Last Fling, the movie that Van and Lucette watch onboard the Tobakoff on the evening of Lucette’s suicide (3.5), suggest that it could be the immemorial line from Blok’s The Commander s Footsteps’. Chyornyi, tikhiy, kaksova, motor (“A black car, noiseless like an owl”). Motor (as automobiles of the early era were called in Russia) rhymes in Blok’s poem with komandor. In both Pushkin’s little tragedy The Stone Guest (1830) and Blok’s poem komandor is the marble statue of the Knight Commander (mentioned in Ada as “the Marmoreal Guest, that immemorial ghost,” 1.18) that, invited by Don Juan, comes to supper to Donna Anna, the Commander’s widow. But this word also occurs in The Golden Calf. Balaganov, a member of

[43]

the Antelope Gnu (Adam Kozlevich’s antediluvian car) crew, calls thus Bender—presumably, because the latter wears a cap of the Chernomorsk yacht-club (komandor means also “Commodore” in Russian).

The invented city on the Black sea (Chyornoe more), the setting of Ilf and Petrov’s novel, Chernomorsk reminds one of Chernomor, the evil sorcerer in Pushkin’s long poem Ruslan and Lyudmila (1820). (The rare oak that grows in Ardis, Quercus ruslan Chat., 2.7, apparently was transplanted from the beginning of the introductory poem to Ruslan and Lyudmila: “U lukomor’ya dub zelyonyi...” “A green oak by the curved seashore...”) On the other hand, it reminds one of Chernomordik (from chyornaya morda, “black muzzle”), the rather improbable but funny name of the chemist in Chekhov’s story Aptekarsha (“The Chemist’s Wife,” 1886). Two men enter a pharmacy not because they want to buy anything, but because they want to see the beautiful wife of the chemist (who is snoring in a back room) at the counter. In order to start a conversation with her, they ask vinum gallicum rubrum (French red wine formerly sold in pharmacies as a remedy) that, when sampled, turns out to be vinum plohissimum (Russo-Lat., “very bad wine”).

A well-known Latin proverb says: In vino veritas (“In wine is truth”). This is what drunks, the habituès of a suburban inn, cry out in Blok’s famous poem Neznakomka (“The Incognita,” 1906):

I p ’yanitsy s glazami krolikov

“In vino veritas!” krichat.

And drunks with the eyes of rabbits

Cry out: “In vino veritas!”

Among Ada's many characters there is one who never appears in the book but is often referred to by other characters: Dr Krolik, the local physician and entomologist, Ada’s teacher of

[44]

natural history. His name means “rabbit” in Russian, reminding one of Blok’s rabbit-eyed drunks. As to the name Veen, of all the main characters of Nabokov’s family chronicle, it means “peat bog” in Dutch but sounds rather like vin, gen. pi. of vino, Russian for “wine.” An anagram of ovin (“bam”), voin (“warrior”) and Vion (as Batyushkov spells Bion, a Greek pastoral poet of the 2nd century B. C.), vino is a key word of Nabokov’s charadoid (the word that seems to be Ilf and Petrov’s invention and occurs in The Golden Calf), the great charade-like puzzle consisting of anagrams similar to those brought up in this article.

Thanks to Sergey Karpukhin and Priscilla Meyer for improving my English, written in 2009

—Alexey Sklyarenko, Petersburg

DEFLOWERING THE MYTH OF ZEPHYR AND FLORA IN NABOKOV’S THE ORIGINAL OF LAURA

This note explores the important network of images relating Flora to her antique original, as we find her in Botticelli’s Primavera as well as in Ovid’s Fasti. The main correlation lies in Nabokov’s treatment of Flora’s defloration (77-81) which constitutes a burlesque echo of Ovid and Botticelli’s illustrations of the myth of Zephyr and Flora.