Download PDF of Number 68 (Spring 2012) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 68 Spring 2012

____________________________________

CONTENTS

Stephen Jan Parker 3

Gennady Barabtarlo

Brian Boyd

Ariane Csonka Comstock

Gavriel Shapiro

Nikki Smith

News 34

by Stephen Jan Parker

Notes and Brief Commentaries 35

by Priscilla Meyer

“Emile Verhaeren and the Earliest Intimation 35

of Potustronnost,’ Nabokov’s ‘Main Theme’”

– Stanislav Shvabrin

“The Movie of E.A. Dupont in Nabokov’s Novel 39

Mashenka"

– Alexia Gassin

“Nabokov On Tour-Part I” 43

– Samuel Schuman

“Correction to ‘Lolita’s Ape: Caged at Last’” 52

– Stephen Blackwell

Annotations to Ada 35: Part I, Chapter 35 53

by Brian Boyd

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 68, except for:

- Brian Boyd’s “Annotations to Ada” (because superseded by, updated, hyperlinked and freely available on, his website AdaOnline).

Dmitri Nabokov

August 2011

[5]

Stephen Jan Parker

This issue of The Nabokovian is a special one, because I am offering it in honor of Dmitri Nabokov who passed away this year on February 22. As a personal, long-time friend of Dmitri, I shall begin this issue with my remarks and some photos. In major newspapers and magazines, many things have already been written about Dmitri, his life and actions, and thus much is publically known. What I shall do here is speak about our special and unique personal friendship.

Let me begin by giving the context of our friendship. I was a student of his father, Vladimir Nabokov, at Cornell University. Subsequently Vladimir Nabokov assisted me when I was writing my PhD dissertation on his Russian novels. Thereafter I became his assistant and worked for him and with him for many, many years. I worked with him in Montreux, Switzerland, and at times my wife and I visited with him there and also in Gstaad, Switzerland where Vladimir and his wife often went during the summers to get away from the mass of summer tourists in Montreux. And then, following his death, I became a close friend of his wife, Véra. I also created the Vladimir Nabokov Research News letter in 1978, which became the The Nabokovian in 1984. I also set up the Vladimir Nabokov Society and have been its Secretary/Treasurer ever since I helped create it in 1979.

The first time I saw Dmitri was when my wife and I were having dinner with Véra at the Montreux Palace Hotel in 1981. After he passed by, Véra explained to us his disastrous automobile roll over off the highway, caused by a tire collapse, while he was driving to Montreux. He had been tossed out the door of his car but caught under it when a terrible fire broke out. He eventually pushed his way free, but had by then been horrendously burned - his hands, his arms, his legs, part of his torso and fractured his neck. He nearly died, but as his mother explained to us, he chose to go on living, and then he spent nearly a full year in the hospital, and when we were seeing him he had just returned home.

[6]

On the boat as we row in Lake Geneva

Famous Chateau de Chillon in the background

In the years that followed, beginning in 1984, I spent several months of several summers working in the Nabokov’s 6th floor apartment in the Montreux Palace Hotel, where Vladimir Nabokov had lived for the last 17 years of his life. My project was to examine, annotate, and eventually publish a detailed list of the one thousand books that were held in the Nabokovs’ apartment and upstairs in the attic in a special book savings room. And while I was working on this project with the wonderful assistance of Véra, Dmitri and I began to get to know each other and we developed a unique, solid friendship that continued to the day of his death.

As it started out, we enjoyed being together so much that we competed in all sorts of things: tennis and ping-pong, running, climbing, and skiing. And several times we went out to fly by hand a large helicopter. He would quite often drive us up to the restaurant at Caux high over Montreaux for wonderful meals. And drove beautifully up and down the winding road. Each summer we drove off rapidly from Montreaux, and he drove

[7]

very well and skillfully his Ferrari, to spend fabulous days in Zermatt, Switzerland. It was a remarkable, special place for the highest possible Alps skiing at the Matterhorn, particularly in the months of August! The skiing was exhilarating. Wc spent most nights up above in an Italian refuge, and some nights down below in a wonderful hotel. Up above we skied, down below we played tennis or marched and climbed, and we also sun-bathed high above among all the beautiful Italian ladies

who came up only to sun-bathe, not ski.

Dmitri picking me up with his car carrying the

flying helicopter

Getting ready to drive in Dmitri’s car to Zermatt

[8]

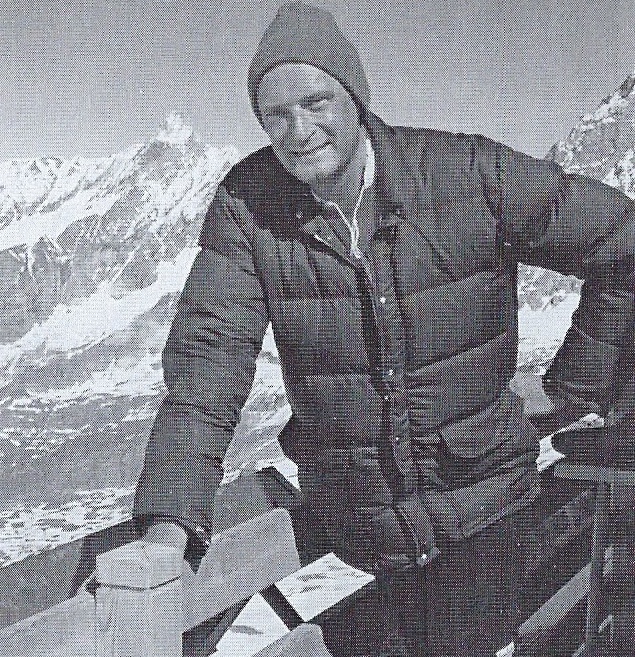

Dmitri up above at the ski area at the Matterhorn

Dmitri having dinner up above at the Italian sleep over place at the

Matterhorn

[9]

Dmitri up above a year later at the Matterhorn ski area

There was nothing ostentatious about Dmitri and nothing snobbish. We had marvelous conversations on various Vladimir Nabokov publication plans and projects; his mother’s will; the establishment of the Vladimir Nabokov foundation; his women friends; our sports; our friendship.

In Montreux we would get together often over many years. Since I spent, and still spend, summers in southern France, I would go off to Montreux by plane, train, or car. And Dmitri also always had a home in West Palm Beach, Florida and then Palm Beach where he lived for a great many years. Since my parents had an apartment in West Palm Beach, I could go there easily. And later on I simply stayed on occasion at his place or nearby. And we would greatly enjoy being together, playing together, walking together, meeting with his friends, driving together, listening to him singing. Indeed he allowed me to drive one of his fabulous cars! In brief, we were simply best friends engaged in many projects and subjects.

We stayed in contact on a regular monthly basis over all the years, by email and by telephone. Dmitri and I met in various places in the USA and abroad. He constantly supplied information and materials for The Nabokovian, and asked and

[10]

Dmitri relaxing at his apartment home in Montreux

allowed me to work with him on a number of projects involving translations of his father’s works. Dmitri read and spoke five languages (Russian, French, English, Italian, German) and thus watched over the correct continuing publication of his father’s works, and he went on translating many works, particularly from Russian into English (which he had done for many, many years), things that had never before been translated, and also most lately, from Russian into Italian.

After his mother’s death he gave me a copy of his father’s unpublished work, The Original of Laura, and for many years we discussed whether or not it should be published. And when he decided to do it, we talked about what would be the best way to put it forth. And most lately what we talked about was

[11]

Dmitri at his apartment home in Montreux

one of his most recent projects, the translation of a collection of letters written by his mother to his father, and its upcoming publication.

Contrary to many opposite statements by people who did not really know Dmitri well, Dmitri had marvelous social graces and showed wonderful hospitality. As I saw him, Dmitri

[12]

was always respectful, attentive, supportive, and loving to his mother. And he was remarkably friendly and hospitable to a great many acquaintances. And to me he was a wonderful, dear friend whom I shall miss for as long as I shall live.

Dmitri and I

August 2011

Gennady Barabtarlo

He died, of a lung infection, in a hospital 17 km from the clinic where his father had died of a similar cause. His lifetime matched that of his father’s within half a year. He was bom when his father was thirty-five, and survived him by as many years. Even the date of his death had an odd echo of the well-known nonplus concerning his father’s birthday: Nabokov Sr.

[13]

was bom on April the 22nd by the N.S., but in his exile chose to mark it on the 23rd; most obituaries reported that Dmitri Nabokov died on the 22nd whereas a few, perhaps more reliable, claimed that it happened at 3 am on the 23rd. These symmetries arrest attention — but their crowding also dulls it; yet neither VVN nor DVN would find them gratuitous.

His father wrote that life “is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of perfect darkness,” the one that precedes man’s coming into existence and the other, to which man is speeding “at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour.” This is said right at the gangway into Conclusive Evidence (of the author’s having existed, per his explanation of the original title), a memoir cut into the patented faceted shape of a Nabokov novel. At its entrance we see the future memoirist gaining awareness of his three-year-old self as he walks between his parents, each holding him by the hand; the next generation’s family trio exits the book in the same fashion, Mitia’s father and mother leading him by the hand from Europe to other shores, pausing on railway bridges in West Berlin, Prague, and Paris as he grows three, four, five, and six years old.

He did not triplicate that pantomime of the threesome. His death cut off the Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov line: both his uncles were childless, he was an only child, with no progeny. The branchy family tree dwindling to naught was practically a natural law in Russian emigration. He never married while his parents — whom he adored with devotion rarely seen nowadays — were alive mainly because their moral and intellectual example set such a high mark and contrasted so sharply with what had become common by the time of his coming of age, that he could not quite imagine any one of the women he courted as their daughter-in-law. And when they both died, he was kept from marrying — once coming very close to — by the set habits of a sixty-year-old bachelor and bon enfant.

His manners and tact were of the old-world charming sort; his mind was sharp and receptive; his vocabulary and verbal

[14]

dexterity in the three European languages he knew well in addition to his native, were prodigious. He was slightly shy about his written Russian, but his speech was of the extinct noble variety, which differed so much from the poor gunky patois now standard in the land of Nabokov’s birth that when he started making televised appearances in the Russian Federation many claimed he had lost his mother tongue. (The same was said twenty years earlier about his father, when the Russian Lolita became freely accessible there). That uncommonly resourceful facility with words across linguistic borders made him a natural early translator and, I think, the best translator of his father’s fiction and verse, first into English and later into Italian. From the 1980s he took upon himself the huge and ever growing management of his father’s posthumous publishing enterprise and of the scrupulous protection of his rights as an author and his honour as a man. In this undertaking he made many more mistakes than in his translations, first shooting voles with a bazooka, then running out of ammunition at the approach of howling hyenas. Publishing the draft cards of Laura his mother had not had the heart to bum as she had been told to was, to my mind (which he knew), the last such mistake. But those who summarily condemned him for “betraying his father” (Russian bloggerheads upbraided him especially fiercely) did not know — and did not trust him when he tried to plant hints in interviews and in the awkward, roundabout preface — that his decision was influenced by the heavy press of material and immaterial circumstances which he hoped would have justified it in the eyes of his father. He had no one whose business and right it might have been to question this supposition, much less excoriate him for it.

He was a man of exceptional faculties. Well-bred at home and educated, thanks to the unsparing efforts of his parents, at first-rate grammar schools, then at Harvard, he received superb vocal training in Boston and Milan, and started on a professional career as an operatic basso. He debuted in La Bohème as Colline,

[15]

a philosopher from the first act; in the last, he pawns his loved overcoat so as to buy medicine for the dying mistress of his pal (played by Pavarotti, also debuting that night). Nabokov, who was in the audience, must have reflected on Gogol’s famous plot turned inside out.

Despite the initial success, his professional career, stretching as it did over twenty years on some of the best stages all over the world, never took wing. It demanded full-throttled, undivided, self-denying dedication whereas he shared it with energy-consuming hobbies, car racing being at the time the chief one — also on the best European stages (a basso profundo Formula One autodrome was right next to his Monza flat). He took numerous prizes, [1]* but this dangerous diversion (race drivers crashed much more frequently and fatally then than they do now) sapped even more nervous energy from his parents, who, like the elderly parents of a demented boy in Nabokov’s 1948 story, waited with sinking hearts by the phone in their Montreux-Palace rooms for him to ring to confirm that he was alive and in one piece after that race as well (“I make the sign of the cross every time he makes that call,” Nabokov confessed to his sister.) In a similar fashion, they had waited at

the bottom of a peak in the Rockies, looking up in the rapidly darkening twilight for their 17-year-old son to come down from a solitary climb that stuck him on a narrow ledge some two miles above them.

He always called, even when, having at last squeezed his six-and-a-half-foot frame out of the window of the enflamed Ferrari that fishtailed out of control on a mundane drive, he rang up his now widowed mother from a sterile bubble in a Lausanne burn unit to tell her, in a faint but tamed voice, stifling the superhuman pain, that he would not be able to make it for dinner as pre-agreed. This, of course, reminds one — as it no doubt did him — of the heroics of some of his father’s heroes,

________

1* Those interested in his motoring tastes can look up a well-illustrated two-part 2009 story by Roger Boylan on autosavant.com(!)

[16]

but it was by no means affected. His literary gift was genuine, too. His translations, both in prose and in verse, combine precision, inventiveness, and elegance to such a rare degree of success that the transformation strikes one as a verbal miracle and becomes an original in its own right. He wrote a large and complex novel and published an excellent, swift-paced memoir in a film-script present tense, Close Calls and Fulfilled Dreams.

Just as his parents, he was a dampproof anticommunist and anti-Soviet, and in general was athwart the sinister bend of the age, sometimes in hyperbolic defiance to whatever its leftist tendencies. He once remarked (in a private letter) that the latest version of the 1,250 hp Veyron (a recent Bugatti supercar) barrelling flat-out at its top speed (253 mph) would run out of fuel in exactly twelve minutes, “a detail I would gladly stuff down the throats of the tree-huggers.” Had his father lived to encounter the term — it entered the American usage the year he died—he might have quipped that one should at least know the name of what one hugs. Like his parents, he never visited the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics; he saw for the first time his father’s former St Petersburg house and the estate in Rozhestveno, not yet burnt down, only in the mid-1990s. It was in a sense a visit to the museum: 47, Morskaia Street had by then been turned in part into a Nabokov memorial, and the city

had received back its original name yet remained the capital of Leningrad Province. Not every fulfilled dream comes true.

From the early forties to the late fifties, in fiction after fiction — in verse, too — his father would place his youngsters in various imaginable dangers and horrors, as if in order to render harmless this particular kind of disaster in life by forestalling it in fiction, counting on fate’s supposed aversion for plagiarism.A lifeless body on a remote hill in “When he was small, when he would fall...”, a strange war-time poem; kidnapped and tortured David Krug; the poor youth tortured in a different way in “Signs and Symbols”; precocious, “up-up-up” tall teenager

[17]

Victor, whose dreams are permeable to Pnin’s, an illegitimate son of his “water father’s” heartless former wife and a witless German bromide, both running him through the gauntlet of frightfully idiotic Freudian tests; lanky Lance vanishing into thin air while his parents stare through their tears into the starry night skies and imagine him scaling the craggy cosmic space as he did the mountains; even Lolita, - - all are part of the perhaps longer series of stand-ins.

He was addicted to high speed — not of the contemplative kind, which tachicardically drives one to the borderline of eternity, but the kinetic, particularly one generated by an internal combustion motor and measured by the tachometer on a dashboard. He raced his 900 hp speedboat in the Atlantic and flew a helicopter over the Mediterranean. It was therefore the queerer and the sadder to see him in a wheelchair puttering about his Montreux flat at the speed of ten manual revolutions per minute. But even months before he died he still hoped to gain back his driving licence.

His father’s next-to-last novel closes on an odd sentence that is supposed to identify the voice welcoming the hero arriving at the other shore. And even though the author took pains to make up a gauche interview with himself in order to clarify that the narrators were spirits of the dead, and that this particular one could be recognized by his knack for jumbling idiomatic bits, it is possible to wonder whether that explanation fully drains the meaning of the “easy does it, you know, son.”

This is a free and enlarged version of the Russian obituary that was published in the Moscow daily Kommersant, in the 27 February issue. G.B.

Brian Boyd

Dmitri Nabokov liked many things, but few better than

[18]

playing the host—a disposition he may have inherited from his father’s father, like his love of music, of telephones and of cars, and another sharp contrast with his own father.

I first met Dmitri in December 1979. I’d just spent a month cataloguing his father’s archives in Montreux for his mother, and was stopping in New York between flights, on my way to see my Canadian girlfriend for the first time in six months.

Meeting Véra Nabokov and then Elena Sikorski for the first time, I’d worn a suit my parents had bought to make me look less disreputable, in their eyes, than the orange or fading purple overalls that had become my second skin. I’d felt and no doubt looked awkward in that alien three-piece, and quickly reverted to, if not the overalls, then jeans, while I was working amid the dusty boxes in the library-cum-lumber-room across the corridor from Véra’s living room in the Montreux Palace Hotel. But visiting Dmitri for the first time, I thought I’d better tog up again.

I rang the doorbell on Dmitri’s apartment just off Central Park, in the East 70s, and there he was, beaming from on high, booming a deep welcome, crushing my hand with his mountain-climber’s grip—and in jeans and T-shirt, before me in my three-piece.

I told him I had something like three hours to spend with him before heading to the airport again. But despite my looking at my watch after a couple of hours, he wanted to keep asking questions of me, even more than I wanted to ask questions of him, and kept doing so as he cooked up a quick but toothsome pasta. I told him I’d miss my plane to Toronto, and my connection to Thunder Bay, but he still wanted to question and answer. I did miss my flights, but he called to arrange new ones—not dreaming that they cost a small fortune for someone who had been a student for ten years, and had spent the first half of the year without an income, while travelling Nabokov trails in the US Northeast, and was now just a postdoc.

Our matching passion for Nabokov and our otherwise

[19]

mostly mismatching styles shaped our asymmetrical friendship. For much of the decade after 1979, I worked closely with Véra when in Europe. I would see Dmitri most often, when he visited his mother from Monza, in the corridor of the Montreux Palace. Near one end was his mother’s sitting room, and at the other, the elevator and the little former laundry cupboard I had transformed into the Nabokov archive room. The moment he emerged from his mother’s, “Hello, Brian” would rumble out like low thunder, while he strode at speed toward me and the elevator, as if he needed to gather momentum for take-off in his Ferrari waiting below.

Headlong haste and hesitation combined oddly in Dmitri. A speedster on the ski slopes, the racetrack and the highway, he could be slow and indecisive as a translator and elsewhere. While working on the biography in Montreux I would often have afternoon coffee with Véra, now quite deaf and rarely on speaking terms with her hearing aids. When Dmitri visited, he would act as a megaphone, relaying to his mother what her ears could not catch of my Kiwi accent. They would often be stumped by a few phrases in a translation, and we would discuss different possibilities, slowly, and reach tentative resolutions. But the next afternoon, and perhaps the next, we would return to the same cruxes, and often assay the same options. The pattern would continue, without Véra, when I stayed with Dmitri in later years.

Dmitri loved participating in interviews and documentaries, and again would bask in the role of generous host. I remember him taking Bronwen and me, and the filmmaker Chris Sykes and his cinematographer and sound recordist, to lunch at his favorite restaurant at Caux, on the slopes above Montreux. He seemed to feel the magnificent terrace 700 meters above Lake Geneva almost part of his demesne, and Helmut, the chef, both part of his staff and a personal friend (Helmut too was an ace skier). A devotee of gadgets and of telephone talk, he would swing his brick-like Motorola resonantly down on the table before he

[20]

sat down, and a meal would rarely go by—certainly neither of the lunches he hosted for the film crew and us—without his being called by friends from around Europe or the Americas. He happily drove his blue Ferrari from Caux down the narrow cobble zigzags toward Montreux, again and again, until the documentary-makers had just the shots they needed.

Just over a year before her death, Véra Nabokov had to move out of the Montreux Palace, and Dmitri advised her to buy an apartment 100 metres above the town, up on the slope toward Caux, with a view matching the one from the Montreux Palace suite, but loftier and more breathtakingly panoramic. After her death he inherited the apartment and made it his home, and his own. He set up his large-scale electric model train to snake through the living room and out into the garden, the freight carriages sometimes transporting a brandy bottle and glasses, and enjoyed his large-scale radio-controlled helicopter while he was also learning to fly a real helicopter. The smaller apartment next door was an extended archive room and guest suite. Another apartment above was for his Italian cook. Not quite “fifty servants, and no questions asked,” but again like his grandfather, and unlike his father, who preferred the Montreux Palace precisely because he need not employ his own staff, Dmitri liked an ample establishment.

I had catalogued the Nabokov archive partly for Véra to consult, partly so that a prospective purchaser would know what was there. No serious buyer emerged until the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature at the New York Public Library signalled its readiness to acquire the papers, by now mostly in the basement under Dmitri’s apartment. Dmitri again showed his indecision, caught between eagerness to sell and reluctance to let the papers go, especially since he feared—this was the height of Russian publishing piracy—that Russian scholars or scoundrels might copy and print the materials. The New York Public Library brought me over from Auckland to Montreux in July 1992 to help persuade

[21]

Dmitri to relinquish the papers, and I was able to break the impasse by proposing that Russian-language materials could be out of bounds, without special permission, so long as he still had grounds to fear piracy.

Dmitri’s love of phone calls—and the further-flung, the better—was another mismatch with my near phone-aversiveness, and even more with the time difference between Montreux and Auckland. Especially in the early years after his mother’s death, Dmitri would occasionally ring, usually at about 4 am our time, to seek advice on some problem: translation, editing, locating a manuscript (for his own reference, and for publishing projects, he had kept photocopies of what the Berg had taken), responding to a publisher or to another affront to the Nabokov name. I would tell him what time it was, but he’d be so eager to talk, and I’d be so wide awake by then, that I’d agree to continue, and try to instil in him again, before saying goodbye, a consciousness of the time difference.

The next time, he would not remember, just as he would not remember that when he gave his time and generously opened his memory and his photo and video collections to those who came to interview him for documentaries about his father, they would always leave the thousands of photographs in chaos. He would still say yes, next time, to the next documentary crew—and perhaps still make the same complaint to me in a new middle-of-the-night call.

Some of the most memorable meals I have ever had have been with Dmitri. He enjoyed the fact that I, unlike practically everyone else he hosted, could eat and drink as much as he: it gave him additional license to enjoy all he wanted. We had three heaped helpings of superb pasta, hardly the lightest of foods, at an Italian restaurant on Montreux’s Place du Marché, where again he treated the cook as an old friend and a faithful servant. When Bronwen and I came to stay with him over Christmas and New Year 1994, he had his cook serve up such rich fare that Bronwen fell ill from the intake. Perhaps it was two nights

[22]

before Bronwen succumbed when Dmitri informed us, looking at his then inamorata, that they were going to announce their engagement in Russia, where they had been imminently invited. The next day I arrived with a bottle of champagne to celebrate the news—and Dmitri looked a little bewildered.

Was it that night, when Dmitri, getting no response from his cook after the first course at dinner, despite his penetrating bass, and realizing she was not in the kitchen or within earshot, dashed from the table as if to her defense? A few minutes later he descended from her apartment, slammed a gun down on the dinner table—he had feared she was being abducted, but she was merely having a row with her ex-husband—with its barrel pointing straight at Bronwen. Bronwen, who had never seen a real gun, let alone had one pointed at her, immediately blanched, and I asked Dmitri would he mind not pointing it at my wife. He was surprised: after all, the safety catch, he assured us, was on.

Two years later the Library of America launched its editions of Nabokov’s English-language novels and Speak, Memory with a reading of Lolita from start to finish, from Humbert’s famous first “Lolita” to his last, in a gallery in New York’s SoHo. Dmitri was to begin the eleven-hour reading. Its complex schedule meant it had to start strictly on time. Knowing that Dmitri’s penchant for speed did not equate to punctuality, the organizers had arranged for a limousine to bring him from his hotel well in advance. Somehow, between leaving his hotel room and reaching the curb, Dmitri managed not to find the limousine driver, and despite frantic calls between SoHo and the Pierre, Dmitri could not be located. Stanley Crouch had to begin, memorably reciting the first chapter from memory. Dmitri eventually arrived late in the first hour.

These were the years when he was at his fiercest as keeper of the flame of his father’s reputation. Before he read out the earlyish substitute passage he had chosen from Lolita, he pulled out a prepared text to extol the Library of America project and

[23]

to denounce would-be dousers and stealers of the flame. After another hour of readings, I left for lunch with Dmitri and our friends, his agent, Nikki Smith, and her husband Peter Skolnik, an intellectual property lawyer especially invaluable to Dmitri in those years of Russian publishing recklessness. I was onto my third beer—was I keeping up with Dmitri this time, or was it just that the beer was so good?—when one of the organizers came rushing in to tell me I was on soon. I had thought my passage still more than an hour away; I have never popped up from a table so fast. As it happened, I did have most of an hour before my turn, but I think those beers added an extra relish of sinister glee to the passage I had chosen, the bedroom scene in the Enchanted Hunters Hotel.

The most farcical of all the meals I shared with Dmitri I can date to April 24, 1999, the day after his father’s hundred birthday. I had spent the birthday itself in St Petersburg and at Vyra, after Nabokov centenary and Pushkin bicentenary celebrations in St. Petersburg and Moscow all week, and I wanted to report to Dmitri about Russia, St. Petersburg, Vyra, the Nabokov celebrations and the Nabokov Museum, which I had visited for the first time. Gavriel Shapiro was also staying with Dmitri, and as it was a Saturday the cook had gone out for the night, leaving ravioli ready by the stovetop. For years Dmitri’s appetite for life had been making him larger, and he was hot in almost any conditions, often leaving doors and windows in his apartment ajar even in winter, and wearing short sleeves and shorts, or less, whenever he could. He was utterly unselfconscious about his body, including the burn scars on his left hand, head, and back from his near-fatal 1981 accident in one of his Ferraris, and about his new girth, and with only two men for company, he happily pottered around the place in no more than his underpants. We sat and talked about the centenary celebrations, I showed the photos I had taken and the posters I had brought, and we discussed translations for Nabokov's Butterflies. We carried on drinking and talking until at about

[24]

10pm we realized we should have some dinner, and moved out to the kitchen to get it ready. Somehow despite Florinda’s preparations, and with nothing more complicated than ravioli as the centrepiece, and with someone who had mastered Italian food decades ago uncertainly at the helm, we managed to turn the preparations into an ordeal worthy of the Three Stooges, even if our timing was not quite so sharp.

This millennium I have seen less of Dmitri, working as I have mostly on literature and evolution, and trying not to work on Nabokov. For much of the last decade he was wheelchair bound, plagued by diabetes and the resultant leg infections, and by polymyalgic neuropathy. The heavy doses of morphine he was on for the polymyalgia almost killed him in 2002. I saw him shortly after, recovering at a clinic, and read on his laptop a first fragment of his splendidly eloquent and elegant memoir. I urged him to continue, to give it priority, but as far as I know he was able to write little more. His eyes, long troublesome, were making work still more difficult.

After every visit in these years I left Montreux thinking I might never see Dmitri again. Then next time he would be still there, a little less mobile, but as gracious and hospitable as ever, letting me work at his computer whenever he left it, letting me roam for what I needed in the archives at any hour of day or night. He put at my disposal, and Olga Voronina’s, the letters from his father to his mother, which Véra had never let me read. (She had kept them in her bedroom, and only after knowing me for five years did she succumb to my repeated requests to have access to them, albeit indirectly, as with a hoarse cough she read the letters aloud, omitting the endearments and more, into my tape-recorder.)

Because of his health, especially his eyesight, Dmitri by now found it hard to undertake sustained projects, but he still enjoyed translating his father’s poems, each its own tough nut to chew on. He hoped to translate all the verse in Stikhi (1979), and although his strength ran out before he could do so, he

[25]

did translate his father’s longest Russian poem, “A University Poem,” finding a flexibility, in an intermittent rhyme scheme of his own devising, that makes this perhaps his finest achievement as a translator.

One of the last times I shared the same sonic space as Dmitri was during a 2008 radio interview for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Book Show, along with Ron Rosenbaum and Leland de la Durantaye. Dmitri had been thinking for years of publishing The Original of Laura. In 2001 he had the index cards transcribed and sent the typescript to trusted friends like Stephen Parker and myself. The more I reread it, the less I felt my earlier recoil from the text that Véra had allowed me to read once, in her Montreux Palace sitting room. I now regretted my advice to her and Dmitri, the next time he had come to Montreux, that they should destroy it. Ron Rosenbaum read a 2007 article by Leland de la Durantaye that he took as a new sign Dmitri might soon bum the manuscript, and appealed to Dmitri through his Slate column not to do so. Dmitri enjoyed, if not the dilemma itself, then the attention the dilemma aroused, and his own power of decision, and the opportunity for Nabokovian mystification. On the ABC Book Show he told us, tongue half in cheek, that he had a visitation or vision of his father approving his publishing the book.

The last time Bronwen and I stayed with Dmitri was in February 2011. Judging by reports of those who visited him later, we arrived at a bad moment. He was still determined to play the host, but Parkinson’s had added to his other troubles and he was locked into a particularly severe attack. We had drinks before dinner, but he could barely speak. That night or perhaps the next—he was much better by then, if still in a sad plight—I asked him, trying to match his perpetual optimism (he would still tell visitors he hoped to drive once more), did he have other Nabokovian projects lined up? “Death,” he answered. He waited for, and savored, our look of horrified concern. Then, after a pause, enjoying the joke, he explained: “I want to translate

[26]

Smert’ [Death]” his dulled eyes still twinkling back and forth from Bronwen to me. All remained intact: the intelligence, the wit, the pleasure of an audience and the pleasure of a host offering what he could to his guests, even this brief glimpse of a free self trapped in a failing body.

Ariane Csonka Comstock

As befitted the son of such parents, Dmitri Nabokov was larger than life; taller, stronger, smarter and luckier than most mortals, yet he could never escape the shadow of his beloved father.

I was one of the few who came to Nabokov through Dmitri; we met in 1977, when he came to Palm Beach to sing a concert for my then-husband, Paul Csonka.

When he came again, three years later, I was divorcing. We began a brief romance, which developed into a relationship that endured through his lifetime, in varying degrees of closeness. It outlasted my marriages, his many affairs, and encompassed half the world, from Palm Beach to Montreux and Chamonix (with his ineffably beautiful mother), Zermatt, Cannes, San Remo and Sardinia.

We had much in common: European parents from a fallen aristocracy, a passion for languages, music and sports. He terrified me with skiing and mountain climbing, but never could beat me at tennis. I challenged him in turn with horseback riding; he was typically fearless, jumping during the first lesson – I teased that it was easy, because, at 6’5 1/2 ” he could put his feet down.

A small boy at heart, Dmitri never lost his passion for model trains and cars. A favorite memory is of the time he took my son (his godson) to fly a remote-controlled helicopter. It was quite a sight; a 6-foot helicopter atop his Ferrari riding through

[27]

Montreux like a giant insect with a beetle in its claws. At the field, he had planned a surprise; a real helicopter appeared, to take us flying through the Alps.

DN was a study in paradox. He loved animals, but never had a pet. He loved women (and how they swarmed around him), but never took a wife. He wrote magnificently, but seldom read. He sang professionally, but rarely listened to music. He was an ardent athlete, yet spent his last decade immobilized in a wheelchair. He loved to laugh, erupting in a booming basso hoot - but never told a joke. We laughed together at human weirdness, at wordplays, puns and the silly limericks he invented so easily.

It was during his last years that I learned to appreciate the rare gift for words which Dmitri inherited, along with the burden and gift of his literary legacy. I worked with him on “Laura”, and in translating many of the stories and poems. And what a joy it was, for one who had translated operas (including “Lolita”), to experience that Nabokovian genius; polishing a phrase, seeking the precise word that would recreate in English his father’s Russian rhythm and rhyme, alliteration, onomatopoeia and imagery.

The absence of that overpowering presence has torn a huge hole in the fabric of our lives. But Dmitri will always be with me, in the resonant tones of a Verdian basso profundo, the flash of a Ferrari clinging to the curves of a mountain road, the sapphirine sparkle of sunlight on the sea, a peaceful morning broken by the roar of a powerful engine –- or a gun shot out the window announcing that it was time to wake up, adventures were awaiting.

I like to think that now he has awakened to the joyous embraces of his mother and father. And after a long interlude of rapturous reminiscing, his father will say, “Splendidly done, my son. But, you know, on page 443 of the Stories, there should have been a comma...”

[28]

Gavriel Shapiro

I met Dmitri for the first time on his birthday, exactly sixteen years ago, even though we had corresponded as early as the 1980s. My then Cornell colleague Michael Scammell invited me to join him on his visit with Dmitri in the New York Hotel Pierre where Dmitri, as his parents before him, used to lodge at the time on his travels to the city. Dmitri invited us to tea at the hotel’s ornate lounge and was most charming and hospitable throughout the entire meeting. He kept the appointment in spite of his being unwell that day: he had a fever, sore throat, and his voice sounded husky. At that first encounter, I was struck by his most imposing 6’6” figure, by the rather unusual robin’s egg color of his eyes, and by his remarkable resemblance to his father.

Throughout the years, I had numerous communications with Dmitri by e-mail, by phone, and in person. His conduct was always most courteous, his kindness and generosity were endless. How many superb translations of his father’s poems did he render upon my request amid his busiest schedule! How invaluable was his eagle-eyed editorship of my far from perfect manuscripts! What an expert and patient teacher of English he was! For example, he taught me to use “As we recall,” and never “As we may recall,” because the latter sounds condescending to the reader. What a gold mine of information he was about his parents for whom he had an infinite reverence and adoration!

Dmitri was a most reliable friend, always ready to come to the rescue. When in 1997, the Cornell Russian Department was under the threat of imminent annihilation, Dmitri singlehandedly saved it by writing, in the tradition of his beloved father, an open letter to the university student paper, The Cornell Daily Sun. In this letter, he protested the Department’s shutdown and rightly called attention to his father’s giving “rebirth and fame to the century-old study of Russian Literature at Cornell.” The Department, alas, is no more, but Dmitri’s miraculous

[29]

intervention had given a few generations of students “the sheer bliss of proper study, within a dedicated department, of one of the world’s foremost literatures.”

Dmitri was a rare breed. In the tradition of his family, his parents and grandparents, he was a Renaissance man. He was always fascinated, in the parlance of his father, both by “the precision of poetry and the intuition of science,” including modem technology. Thus, one day, he told me over the phone that he was building a computer to his own specifications.

He possessed an enormous linguistic aptitude and literary talent. Here is but one example. During one of my visits to Montreux, while we were having lunch, a package arrived. It contained an English translation of one of his father’s earlier Russian stories. Dmitri found this translation adequate, but it was clearly not up to his standards. He then suggested that “we” go over the translation “together.” Of course, I was merely an apprentice in his master class. And the master class it was! It was astonishing to be privy to Dmitri’s creative lab, to hear his enormous vocabulary in both languages, to listen to the dazzling array of synonyms that he tried one by one until finding the best locution. In the end, he magically turned the initial adequate rendition into a true chef d'oeuvre.

As we all know, Dmitri was a most accomplished opera singer. It is less known that he also had exquisite taste and supreme erudition in the fine arts. On my visit to West Palm Beach, I brought him a catalogue of the Metropolitan Museum exhibit that he wanted to, but was unable to attend. While leafing through the catalogue, Dmitri made profound observations that would have made any art historian green with envy.

In his younger years, Dmitri was an avid athlete: boxer, tennis player, mountain climber, prize-winning car and boat racer, and helicopter pilot. One day I got an inkling of just how good Dmitri was in these sports which require dexterity and presence of mind: when I was taking him to the hospital with a ruptured Achilles tendon, it was he who, in spite of the

[30]

excruciating pain, was not only navigating but in fact helping me operate the SUV through the serpentine streets of Montreux by having a hold on the steering wheel, thereby giving me the most memorable, and quite necessary, driving lesson.

I spoke with Dmitri for the last time shortly before the New Year. His sonorous voice, as usual, was brimming with energy. Dmitri was very pleased when I suggested a visit with him in July. His last words were: “Buduzhdat'!”(“I shall be waiting!”)

When on February 23 I received the news about Dmitri’s passing, my very first reaction was of shock and disbelief: “It can’t be, there is some mistake here.” I was shaken to the core, and physically felt a great void: “Dmitri is no more.” As time has progressed, I began to realize that although his body is not here, his spirit is ever-present. Now when I cannot e-mail, telephone, or visit him in West Palm Beach or in Montreux, I frequently talk to him in my mind and do not feel the loss as acutely as at the very first moment. Pondering about Dmitri brings to mind Ivan Bunin’s magnificent “Light Breathing” which Dmitri, like his father, held in high esteem. To paraphrase slightly the story’s closing lines: “Dmitri’s gracious breathing got dissipated in the world, in these cloudy skies, in this cold spring wind.” Dmitri continues to ennoble our lives and to suffuse them with beneficence and spirituality.

Nikki Smith

When his mother died, Dmitri Nabokov asked me to speak at the memorial service he arranged for her not far from Montreux. I said what I had to say; and as I left the podium, failed to see the step. There was her son, on his feet, his hand gripping my arm. That was Dmitri: alert to the impending disaster. The self-elected, self-serving Nabokov scholars; the typos. The copyright infringers, the rush of a culture that threatened to

[31]

bury the past; the eulogist about to fall on her face. He rose to the occasion, looking, even then, like his father, and gifted with his mother’s warm, unassuming manner. Canned soups were fine; bargain basement wines; apartments wallpapered and furnished, however dubiously, by the prior occupant. Visitors were apt to find him in shirt tails and flip flops.

When he delivered me safely to my seat that day, Dmitri went to the podium to deliver his own eulogy for his mother. He wasn’t good at keeping things—phone numbers got lost, schedules, diets, a copy of the first edition of Lolita inscribed to him by his father. Following the death of his mother, he would begin to lose much of what was his own, including, to his occasional dismay, the privacy he had as the only child in the house of an émigré professor and his wife. With age went the voice that climbed through opera venues in Rome and Istanbul. What he referred to as “the toys” would go—the model train that whistled around the floor of his dining room in Montreux was packed away; the souped-up cars and boats that unnerved his parents sat unused. But what he would hold on to was the impulse to be a good son.

That impulse is writ in the Nabokov translations he undertook with his father, and later his mother. He would outlive her by nearly 21 years, and that impulse would keep him on his feet even as he was confined to hospitals and wheelchairs. He would complete what she had undertaken: he sent the Montreux archives, sealed and unsealed, to the New York Public Library; collected, annotated and translated the balance of the Nabokov stories—behind schedule, they appeared late in the year to become Book #11 on the New York Time's list of the ten best books of the year. He would do what she would never have done: she’d elected to open the archives to Brian Boyd, resulting in the magisterial two-volume biography of her husband; Dmitri opened the archives to Stacy Schiff. who won a Pulitzer prize for her biography of his self-effacing mother.

His mother said that she would never return to Russia; on

[32]

his father’s 100th birthday, Dmitri went. Feted in a St Petersburg released from the Soviet thumb, he met a young scholar, Olga Voronina, who, some five years later, would set in motion what became the first royalty-bearing edition of Nabokov published in Russian in Russia. Among the volumes Dmitri would authorize: the first collection, Andrey Babikov’s, of all of Nabokov for, and on, the theatre; Gennady Barabatarlo’s Russian translations of The Real Life of Sebastian Knight and, the novel embraced in some quarters as the anthem for a new kind of Russian, Pnin.

If his mother mourned the inattention given Nabokov the poet, Dmitri—his ear tuned to the air-borne sound of a living, breathing Nabokov—would authorize, for performances in theatres filled with living, breathing human beings, stripped- down versions of Lolita: A Screenplay. It premiered in Milan under his supervision; other versions played in Germany, in Bucharest, Ljubljana, at the Abbey in Dublin; last I knew, it was headed for Paris.

Would his mother have welcomed the internet or released The Original of Laura? Her son wasn’t certain, but he would applaud the best of the VN websites and toy with the notion of a website for Laura so that Nabokovians could join him in playing cards.

Did he have a good time? There is, I think, no question that the family business of keeping VN up and running enlarged and heartened his mother. In some sense, the role of businessman of letters would diminish Dmitri. Superbly educated, graceful, volatile, rendered, in effect, stationary, he would miss—a good-enough metaphor here—the open road.

And the readers of Nabokov? He would enlarge their numbers, many times over. It may be that he came to trust them rather more than his parents did, but there is no question that on his death their good son would leave Nabokovians enriched: smarter, wiser, more exuberant, better equipped to see. Therein resides honor.

[33]

The burial spot of Vladimir Nabokov in Vevey, Switzerland, where

both his wife’s and now his son’s ashes are buried.

[34]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

This is a very special edition of The Nabokovian, since it is the only issue that has ever been dedicated to an individual. The most important contributor of information and texts, and most important monetary contributor, to the Vladimir Nabokov Society and The Nabokovian, has been Dmitri Nabokov. He has been closely linked to the Society and its publication for many decades. And thus this is a unique and highly special edition.

***

Nabokov Society News

Unfortunately the membership/subscription figures in 2012 have continued to drop, and the financial situation for The Nabokovian publication, with the absence of Dmitri and therefore his continuing support, is now critical. A remarkable number of members this year have sent in significant contributions to help keep The Nabokovian alive – and I send them a most heartfelt “thank you” for their wonderful support. But the reality is that we are still about $2,000 short. We shall continue to publish this coming fall, and then the following year. And by then I hope that things get better and the printed Nabokovian can continue to exist.

Once again, and now for the 33 rd year, I wish to express my truly greatest appreciation, along with the appreciation of the Nabokov Society, to Ms. Paula Courtney for her continuing, exceptional assistance in the production and publication of The Nabokovian.

[35]

NOTES AND BRIEF COMMENTARIES

By Priscilla Meyer

Submissions, in English, should be forwarded to PriscillaMeyer at pmever@wesleyan.edu. E-mail submission preferred. If using a PC, please send attachments in .doc format. All contributors must be current members of the Nabokov Society. Deadlines are April 1 and October 1 respectively for the Spring and Fall issues. Notes may be sent, anonymously, to a reader for review. If accepted for publication, some slight editorial alterations may be made. References to Nabokov’s English or Englished works should be made either to the first American (or British) edition or to the Vintage collected series. All Russian quotations must be transliterated and translated. Please observe the style (footnotes incorporated within the text, American punctuation, single space after periods, signature: name, place, etc.) used in this section.

EMILE VERHAEREN AND THE EARLIEST INTIMATION OF POTUSTRONNOST’, NABOKOV’S “MAIN THEME”

As the focal point of this issue of The Nabokovian must sadly be the passing of Dmitri Nabokov, 1 too would like to dedicate my brief note on the most important theme of Vladimir Nabokov’s art to the memory of his son. Since contacting him for the first time more than a decade ago, I continued to be in touch with him until what proved to be the last two years of his life. Whenever I found myself in need of his advice I got it; whenever I asked him, he shared with me his recollections of his parents’ life and work, supplied me with insight and materials that were as invaluable as they were unequalled in depth and consequence. I will never forget his calls on my mobile phone at some of the most intense stages of my share

[36]

of work on the preparation of the manuscript of The Original of Laura for publication, and I can only regret that I may not convey the full extent of his exuberance should I attempt to re-capture it in words; I will treasure his correspondence with me as a manifestation of his sense of humor, attention to detail and willingness to come to one’s aid when he was uniquely positioned to do so. I owe Dmitri Nabokov my very ability to contribute this present note to The Nabokovian, as without his encouragement and permission I would not have been able to access the restricted sections of his father’s archive or undertake my exploration of the ways in which his father’s original creativity is informed by his life-long interest in translation.

* * *

In his seminal article “Nabokov and Rupert Brooke,” D. Barton Johnson points out that “Nabokov’s first use of the term potustoronnost’, the ‘hereafter,’ occurs as a preliminary to his discussion of Brooke’s poem ‘The Life Beyond’” (see Nabokov and His Fictions: New Perspectives, ed. by Julian W. Connolly, Cambridge UP, 1999, p. 187). Introducing a line of interpretation that was to be developed later by its other adherents (its germ is discernible in the biographical writings of Andrew Field, yet most recently and eloquently it has been reinvigorated by Alexander Dolinin), Johnson surmised that “the ‘hereafter’ theme,” apparently missing from Nabokov’s juvenilia, was “launched” by the March 1919 death of Yuri Rausch von Traubenberg, a tragic event that suddenly rendered death a reality for the future writer (see ibid.). There is ground to believe, however, that Vera Nabokov’s retrospective disclosure of potustoronnost' as the main theme with which her late husband’s oeuvre is shot through may turn out to be even more far-reaching in its scope than it was taken to mean initially (see her laconic preamble to her husband’s Stikhi [Anna Arbor, 1979]).

[37]

Conspicuously absent from his earliest published output, the first formulation of potustoronnost’ - the hereafter, the otherworldly, the beyond or the otherworld, as it has been alternatively conveyed in English -- does nonetheless occur in a poetic exercise that dates to Nabokov’s pre-exilic, pre-Crimean days in his native Petersburg-Petrograd. Given that translation held the status of a deeply personal mode of expression for the future writer from the earliest stages in his artistic evolution (in connection with which one is reminded of his first published work, an appropriative Russian rendition of Alfred de Musset’s “La nuit de decembre,” 1914, the relevance of which has been persuasively demonstrated by Jane Grayson), it should not come as a surprise that so important a theme must have found an initial outlet for itself in this and not any other medium or guise.

Among other unpublished, uncollected poems and translations penned in the period between September/October—November, 1917, and dedicated to Ewa Lubrzinska, “Stikhotvoreniia,” the manuscript album B (now in the Vladimir Nabokov Archive with the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, New York Public Library) preserves Nabokov’s translation of “Les voyageurs” by Emile Verhaeren (1855-1916). First reproduced in the collection Les Soirs dedicated to a fellow Belgian poet Georges Rodenbach (1887), “Les voyageurs” is a short narrative poem that encompasses eleven quatrains of enclosed rhymes. In full agreement with the principles of Verhaeren’s brand of Symbolism, “Les voyageurs” is a tra vel narrative that is highly allegorical in nature. It tells the tale of the unnamed wanderers who are quick to part with their nondescript homeland as they respond to “the strange echo of pensive horizons” and heed “the

ancient call of distant sibyls” (the poem’s opening quatrain reads: “Et par l’étrange écho des horizons songeurs, / Et par l’antique appel des sybilles lointaines, / Et par les au-dela mystérieux des plaines, / Un soir, se sont sentis hélés, les voyageurs”). Having visited a number of ancient, enigmatic lands, the poem’s

[38]

protagonists, the voyagers – much like the anthropomorphized “drunken boat” of Rimbaud’s eponymous poem (1871) – must return home, yet they will never be the same, as every fiber of their existence has now been irreversibly altered by their encounter with “other firmaments” (the poem’s concluding quatrains reads: “Car les soirs leur seront de tourmenteurs aimants, / Les soirs et les soleils ouverts, comme des portes, / Sur leurs rêves défunts et leurs visions mortes / Et leurs amours nimbés par d’ autres firmaments,’ ’ see Émile Vérhaeren, Poèmes, Paris, 1911, vol. 2, pp. 51-54).

In his equilinear Russian version of this poem, Nabokov saw fit to translate its opening quatrain’s third line .. [p]ar les au-delà mystérieux des plaines..as “tain plenitel’nykh ravnin potustoronnikh” (“[of] enthralling mysteries of otherworldly prairies”). While on the superficial level this choice of an epithet may be interpreted as a mere manifestation of the asymmetry of the original in its poetic foreign-language representation, its significance is greatly amplified by the role allotted to its nominal variant as the centerpiece of Nabokovian mythopoetics, the writer’s personal denomination of his intuition of a plane of being ostensibly located beyond the divide separating life from death.

In his essay “Dante sovremennosti” (“Modern-Day Dante,” 1913), the doyen of Russian Symbolism and principal champion of Verhaeren in his and Nabokov’s homeland Valery Bryusov (1873-1924) aptly highlighted the mystical orientation of “an entire period of [Verhaeren’s] work (Les Soirs, Les Débacles, Les Flambeaux noirs, and partially Les cloître),” a period that was “devoted to his attempts with the force of intuition, with epiphany that was artistic rather than religious, to peer beyond the border of the accessible to cerebral knowledge” (“.. .tselyi period ego deiatel’nosti [Les Soirs, Les Débacles, Les Flambeaux noirs, otchasti i Les cloître] byl posviashchen popytkam siloi intuitsii, esli ne religioznogo, to khudozhestvennogo prozreniia zaglianut’ za predel dostupnogo znaniiu, rassudochnomu...”

[39]

[see his Izbrannyesochineniia, Moscow, 1955, vol. 2, p. 239]).

While amplifying the tacit significance of Verhaeren’s “Les voyageurs,” Nabokov’s choice of an epithet serves as additional testimony to his consistency in his devotion to the “main theme” of his art, one that owed its formulation to his insistent dialogue with other creative minds, one conducted through the medium of literary translation.

—Stanislav Shvabrin, Princeton, NJ

THE MOVIE OF E. A. DUPONT IN NABOKOV’S NOVEL MASHENKA

During his years in Berlin, Vladimir Nabokov, like many other Russian emigrants, used to work as an extra for German films produced by the Babelsberg Studios in Potsdam. The subject of Russian extras in foreign movies was studied in detail by the Russian researcher Rashit Yangirov in his work Raby nemogo. Ocherki istoricheskogo byta russkikh kinematogrqfistov za rubezhom 1920-1930-egody (Slaves of the Silent. Studies in the history of Russian filmmakers abroad in the 1920s-1930s, Moscow: Russkiy Put’, 2007). In the spring of 1925, this topic was al so discussed in the Russian daily, Rul' (The Rudder) (1920- 1931). The article “Russkie statisty v kino” (Russian extras in the motion pictures) reported that the German production company Terra-Film used about four hundred Russian extras for its films, since it could pay them less than German extras, who were employed by the “Paritätische Börse” (“Joint Market”). This state of affairs angered many Berliners, which compelled the German ministry of Labor to issue a special request for the studios not to employ Russians in movie-making. The reporter concluded his article with a statement defending the emigrants: “Nado skore vinit’ bogatye kinematograficheskie obshchestva,

[40]

chem nishchikh russkikh statistov” (“It would make more sense to blame the rich production companies than the poor Russian extras” [“Russkie statisty v kino,” Rul', Berlin: Ullstein, 1925, 1319, 4, my translation]).

In his first novel Mashenka, published in March of 1926 by the publishing house Slovo in Berlin, Nabokov tells the story of one of his experiences as an extra. It was in a movie in which he appeared very briefly. He emphasizes the depersonalization and the loss of identity of a Russian émigré when he/she works as an extra amongst the masses the directors fix on film. This episode was described by Nabokov’s friend Ivan Lukash and is recounted by Brian Boyd in his biography of Nabokov: “One film required a theater audience, and because Nabokov in his old London dinner jacket was the only one in evening dress, the camera lingered on him” (Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov. The American Years, 1940-1977, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991,205). Presumably, this episode in Nabokov’s life took place in April 1923. However, one can question this date, because we are told a few lines later in the biography, that the writer will use this moment very “soon” in Mashenka, which

he wrote in the fall of 1925 (Vladimir Nabokov. The American Years, 205). Therefore we can assume that the exact timing of this episode in the writer’s life cannot be specified properly, especially as Nabokov himself admitted “not to remember the names of these movies” he took part in (Vladimir Nabokov, Strong Opinions, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1973, 161). However, we can restore the missing information by analyzing the text of Mashenka.

In the novel, the main character, Ganin, is watching a movie in a local cinema in Berlin. The following scene is described: “A prima donna, who had once in her life committed an involuntary murder, suddenly remembered it while playing the role of a murderess in opera. Rolling her improbably large eyes, she collapsed supine onto the stage” (Vladimir Nabokov, Mary, London: Penguin Books, 2007, 24). This scene is based on the

[41]

movie of the German director Ewald AndrEe Dupont, entitled Der Demütige und die Sängerin (The Humble Man and the Singer), produced in 1924 by the company Terra-Film, which premiered on April 2nd 1925 in Berlin. This movie is a screen adaptation of the eponymous novel of the German writer Felix Hollander, published in the weekly Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (BIZ) in 1924.

The movie tells the story of Toni Seidewitz, performed by the famous actress Lil Dagover, a young woman with a wonderful voice who dreams of becoming a great opera singer. Encouraged by her mother, a failed actress, Toni accepts a proposal to marry the rich and brutal manufacturer Liesesang (played by Hans Mierendorfif), who promises to help her start her career by paying for her singing lessons. However, once Liesesang realizes that Toni could actually be successful, he makes sure that it does not happen, for fear of losing control over her. Desperate (she tolerates violence of Liesesang for the sake of her career), she confides in Raimundi, a young Italian who is secretly in love with her. In order to help her and to show his love, Raimundi kills Liesesang with an overdose of sedatives administered when the manufacturer is sick. Toni feels guilty and rejects the advances of Raimundi. As a consequence, Raimundi commits suicide. Toni goes back to Berlin to find a job “[um] die Toten [zu] erwecken” (“in order to wake the dead” [“Der Demütige und die Sängerin,” Zensurkarte, Berlin, 18.03.1925, 10101, 6, my translation]). Using her voice and performance, she wants to bring herself as well as the others back to life. She becomes the leading singer in Carmen and signs with the opera house, where she has to sing an opera, entitled The Murderess, for her friend and composer Wladimir Kreuzer. When Toni is to sing the lyrics “Ich bin die Mörderin” (“I am the murderess” [Zensurkarte, 8, my translation]), she collapses on the stage, overwhelmed by her feeling of guilt. According to the film critics, this scene is the best scene of the movie: “Geradezu verblüffend die Szene in der Oper” (The scene in the opera is quite amazing [“Der

[42]

Demütige und die Sängerin“, Lichtbildbühne, Berlin, 44, 37,

my translation]).

Thus the last scene of the film definitely takes place in a theater. Incidentally, a picture of this scene was released in the film periodical Kinematograph (“Der Demütige und die Sängerin", Kinematograph, Düsseldorf, 916, 22). This allows us to draw a parallel between this closing scene and the scene in Nabokov’s novel, in which the author gives his personal touch when parodying the scene in the following description: “Now the scene showed an aging, world-famous actress giving a very skillful representation of a dead young woman (Mary, 25). He adds the fact that Lil Dagover is aging (she was 38 years old at the time) in order to caricature the femme fatale. That is probably the reason why he gives a special place to Lyudmila in this scene-she is sitting beside Ganin during the viewing of the movie. She is actually the opposite of a femme fatale. Furthermore, according to the writer, the young opera singer should die to pay for her fault, while Dupont’s movie has a happy ending: after she regains consciousness, Toni tells her story to her friend Wladimir, who doesn’t leave her and supports her. The composer thinks that the murder of Liesesang should be considered a “sacrifice for art,” since Toni was entitled to sing in exchange for her life. Finally, we assume that Nabokov described this episode of his life in Mashenka to suggest that he had not recovered from the way he was treated by the Babelsberg Studios, which apparently treated their extras with contempt. In his autobiographical memoir Speak, Memory the writer explains that he loses a part of his life once he writes it down: “I have often noticed that after I had bestowed on the characters of my novels some treasured item of my past, it would pine away in the artificial world where I had so abruptly placed it” (Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory: An Autobiography Revisited, New York : G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1966, 75). These special moments of his experience, then, don’t belong to him anymore. It seems that he gets free from his memories, which come alive through

[43]

other characters again, when he relates them to his reader. We could speculate that by describing this real episode as an extra and externalizing what happened in the studio, Nabokov performed a kind of psychotherapy, allowing him to “forget” his brief appearance in Dupont’s movie. Moreover, the use of The Humble Man and the Singer is a way for Nabokov to emphasize Ganin’s gradual transformation into a shadow on the screen and into the life of the character.

—Alexia Gassin, Paris

NABOKOV ON TOUR—PART I

In 1942, still a relative newcomer to American academic and literary life, VladimirNabokov embarked on a small lecture and reading tour of seven Southern and Midwestern colleges. He was seeking to supplement the meager income he would earn in 1942-43 from his work at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. The tour was arranged by the Institute of International Education, founded after the First World War to encourage global understanding.

Nabokovians have two readily available sources of information about the 1942 tour. Brian Boyd’s Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years:(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991) offers the history of the period from September to December of that year (pp.48-53; and footnotes on pp. 679-680). The first part of the trip lasted about a month, from the end of September to the end of October, and included stops at Coker College in Hartsville, SC; Spellman College in TN; Georgia State College for Women in Valdosta; and The University of the South in Sewanee, TN. After a brief respite at his home in

[44]

Cambridge, he was back on the road in early November, speaking at Macalester College in St. Paul, MN; and Knox College in Galesburg, IL. He returned again to Cambridge on November 18, and made one more collegiate excursion in December to Longwood College, in Farmville, VA. The entire venture, Boyd reports, was not a fiscal success.

A second perspective on these travels are the letters (in the VN Archive, a major source for Boyd’s history) that Nabokov wrote home to his wife. Excerpts from five of them were published in The New Yorker as “The Russia Professor: The Author on Tour” (June 13 & 20, 2011, 100-104, tr. Olga Voronina and Brian Boyd, with Dmitri Nabokov). The letters are from Hartsville; Atlanta; Valdosta; Springfield, IL; and St. Paul. They offer a touching and often humorous account of Nabokov’s experiences at the colleges and on the road, as well as a glimpse of his communications with Vera.

Student and regional newspapers, yearbooks, press releases, and letters from those seven institutions provide an interesting glimpse of how the 43 year-old Nabokov was received in academic America at the beginning of his career as an English language writer.

Similar biographical information is included in several of the different collegiate previews of Nabokov’s visit, drawn from a description of VN which the Institute for International Education used to introduce Nabokov to the collegiate market [cited in Boyd’s The American Years, FTNT, 679.] That biography includes VN’s St. Petersburg youth, his father’s liberal political activities, the flight from the Bolshevik revolution, Nabokov’s English education and his immigration to the United States, and a summary of his writing career as of 1942. It lists eight prepared lectures and talks on four authors which VN was prepared to deliver [Boyd, The American Years, 43].

We begin with Coker College.

[45]

II.

Hartsville, the home of Coker College, is in central South Carolina. The college celebrated its centennial in 2008, and was until the 1960’s a small liberal arts school for women: it is now co-educational and has a student body of about 1100. At the time of Nabokov’s visit, it was affiliated with the South Carolina Baptist Convention.

Nabokov’s letter to Vera dated October 2-3, 1942 from Hartsville details his Pninian and comical “vilest of trips” from New York to South Carolina. Boyd (49-50) recapitulates the tale. After missing the connecting bus to Hartsville, VN was temporarily stranded in the “heat and sun” of Florence, some 25 miles from the campus. The College promised to send a car, and a comical series of miscommunications ensued. These were caused, in part, as Nabokov joked in his letter to Vera, because “the college was expecting a gentleman with Dostoyevsky’s beard, Stalin’s mustache, Chekhov’s prince-nez, and a Tolstoyan blouse.” He arrived only in the nick of time for a dinner party in his honor, before which he took a quick bath then lost a cufflink. A substitute cufflink was eventually offered, and from then on, everything proceeded smoothly.

Nabokov was, along with Elizabethan scholar Hardin Craig, the headliner of the three-day Coker College Literary Festival, speaking three times. There are several items in the Coker College archives relating to this visit. (My thanks to Nancy Matthews who serves as archivist at the Coker College Library.)

The college newspaper, The Periscope, of September 30 previews the literary festival. The article begins: “Vladimir Nabokov, who has been called ‘the greatest Russian novelist writing today, ’will open the fifth Coker College Literary festival on the evening of October 1.” The remainder of the article follows the standard biographical blurb cited above.

This material in the student newspaper comes, almost word-for-word from a college press release of September 27,

[46]

entitled “Coker Literary Festival To Be Held October 1-3.” The release includes an expanded biography and adds (also from the Institute on International Education information):

Professor Philip E. Moseley, Cornell University, writes:

“I should like to add that in my own opinion, and in that of

many far better experts than myself, Mr. Nabokov (under

his pen-name of ‘Sirin’) is already the greatest Russian

novelist writing today, and contains infinite promise of

ever greater achievement - I use these superlatives about

his writing deliberately, for I have been reading his work

in Russian since 1932.”

The release also includes a brief biographical and bibliographical blurb from The Atlantic Monthly of November, 1941, where “Cloud, Castle, Lake” and “The Aurelian” appeared—VN’s first publications in an English language periodical.

The program of the Fifth Annual Coker College Literary Festival (“contributing to the literary renaissance of the South”) October 1-3,1942, lists, as noted above, Nabokov’s participation. The conference began with the dinner VN almost missed followed by Nabokov’s talk on “The Art of Writing” and a reception on the evening of the 1st. Interestingly, in his letter to Véra, Nabokov describes his initial talk somewhat differently: “I spoke on ‘common sense’ and it turned out - well, even better than I normally expect.” (This is a version of “The Art of Literature and Commonsense” published in Fredson Bowers, Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980, 371-380. This talk was the backbone of all of Nabokov’s collegiate visits.) The next day, Friday, October 2, Nabokov spoke at 10:15 AM on “The Novel,” and at the same hour on Saturday, October 3, delivered his lecture on “The Short Story.” Again, somewhat contrary to the official program, Nabokov himself describes his final talk on Saturday

[47]

as “The Tragedy of Tragedy.” This lecture, according to Dmitri Nabokov, was written for Nabokov’s summer course on drama at Stanford in 1941 [For the lecture and Dmitri Nabokov’s introduction see The Man from the USSR and Other Plays', San Diego: Harcourt, 1984, pp 311 ff.] Besides a brief biography of Nabokov, the program recapitulates the information from the press release. It also notes that the festival “is distinguished by a list of speakers – all working practically and professionally in the field of creative literature. You will have ample opportunity to meet them, and talk with them - and, yes, collect autographs – if you can.” Books will be on display throughout and the authors represented “will gladly autograph them for you.” As a “special feature,” it notes that “Thursday evening after Mr. Nabokov’s lecture, all are invited to the drawing room to meet the speaker, and others on the program.”

Two other opportunities to mingle with the guests are a book tea Friday afternoon and an open house on Saturday from 3:00 until 5:30.

The final citation of Nabokov’s visit to Hartsville is from the 1942-43 Coker College yearbook, “Milestone,” edited by a student, Peggy Burnet. Under the title of “The Outside World,” the yearbook notes that

The Literary Festival came and with it Archibald

Rutledge, South Carolina’s own poet; Vladimir

Nabokov, Russian novelist and word artist; Dr. Hardin

Craig, noted Shakespearean authority, at present

Professor of English at Chapel Hill.

The yearbook citation is accompanied by a picture of Nabokov, presumably at Coker, standing outdoors and looking lean and dapper, head slightly tilted and with a somewhat bemused expression on his face, wearing a suit and tie, and with a cigarette burning in his right hand.

Boyd notes that Nabokov had to dress in formal attire for

[48]

three dinners in a row at Coker, and that he amused himself during his (relatively slight) free time by chasing both insects and tennis balls, the latter driven by the College’s best player; that he went canoeing; and that he received $100 plus his meals and lodging for the three day stint.

Nabokov assured Véra, addressed as “my dear sweetheart,” that she should “not imagine that I am running after Creole girls here. Here they’re more the Miss Perkins type and the younger women have fiery husbands; I barely see any girl students.” He is referring to Agnes Perkins, his colleague in the English Department at Wellesley; see Sarah White’s letter at

www.newyorker.com/magazine/letters/2011/07/s11/110711/ mama_mail3.

These materials suggest that Coker College’s perception of Vladimir Nabokov was appreciative and accurate. It is possible there was some miscommunication regarding the topics of his three talks, but there is no indication this actually caused any problem, since all the topics VN mentions, or are cited in the program, are on list of his presentations from the Institute of International Education. In his early 40s, VN seemed to these students, and their literary mentors, to be a somewhat exotic Russian man of letters. They find his Slavic background

interesting, note his creative endeavors, and also are impressed by his literary scholarship. It is, perhaps, a telling clue that the only material written after Nabokov’s appearances, the 1942-43 yearbook, adds to his credential as “novelist” the glowing description “and word artist!”

III.

The next stop on the tour was Spellman College in Atlanta, which Nabokov described as “a black Wellesley.” (I am grateful for the help of Kayin Shabazz and Taronda E. Spencer at Spellman and the Atlanta University Center for their archival assistance in Atlanta.) On October 7, he notes that he finds “the woman president very nice indeed.” That President, Florence

[49]

Read, is described by Brian Boyd as “a vibrant, astute older woman who surrounded him with every attention and would become a long-term friend of the Nabokov family.” President Read, a graduate of Mount Holyoke college, served as President from 1927 until 1953, and was the last White person to lead Spellman (her successor was Dr. Albert Manley, the first Black and the first male to serve in that role). In The Story of Spelman College, a collegiate history by President Read (Atlanta, GA, 1961) is a list of important speakers at the school, including Ralph Bunche, Martin Niemoeller, Langston Hughes, Stephen Spender and Louis Untermeyer. Most of those individuals are simply identified, but when Dr. Read gets to Nabokov, she writes “poet and novelist (an inspiring visitor for six days).”