Download PDF of Number 7 (Fall 1981) Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter

THE VLADIMIR NABOKOV

RESEARCH NEWSLETTER

Number 7 Fall 1981

______________________________________________

CONTENTS

1981 Annual Meeting

The Vladimir Nabokov Society 3

News Items and Work in Progress

by Stephen Jan Parker 4

David Cronenberg: A Postscript

by Timothy R. Lucas 10

Abstract: David Lowe, "Nabokov's Hermann:

Homme sans moeurs et sans religion!"

(AATSEEL paper) 16

Annotations & Queries by Charles Nicol

Contributors: Pekka Tammi, D. Barton Johnson 19

From a Family Album 25

Abstract: Priscilla Meyer, "Nabokov’s Lolita and

Pushkin's Onegin: A Colloquy of Muses"

(article in progress) 33

Abstract: Jonathan Borden Sisson,

"Cosmic Synchronization and Other Worlds in

The Work of Vladimir Nabokov"

(Ph.D. dissertation) 35

Abstract: Nancy Garfinkel, "The Intimacy of

Imagination: A Study of the Self in

Nabokov's English Novels"

(Ph.D. dissertation) 38

Bibliography

by Stephen Jan Parker

Contributor: Grove Koger 40

Reminder 51

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 7, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

[3]

1981 ANNUAL MEETING THE VLADIMIR NABOKOV SOCIETY

The annual meeting of The Vladimir Nabokov Society will be held in New York City on Wednesday, December 29, 7:00-9:00 pm, in the Broadway Suite of the Roosevelt Hotel (Madison Avenue at 45th Street). The Society meeting is part of the official program of the National Convention of AATSEEL (American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages). And, as is almost always the case, AATSEEL's convention is being held concurrently with the MLA convention, which should insure a good turnout for the session.

The meeting will be chaired by Samuel Schuman, President of the Society. Participants in the formal program, under the title "Nabokov … and Others," will be: Gladys M. Clifton, "John Shade's Poem: Nabokov's Subtlest Parody;" Alex E. Alexander, "Alice in Humberland;" Susan Vander Closter, "A Discussion of The Gift;" Sergei Davydov, "Models, Mimics, and the 'Matreshka-Technique' in Nabokov's 'Lips to Lips';" respondent, Beverly L. Clark; special presentation, Nina Berberova, "Nabokov's Readings: Nabokov's Readings in English Literature Before the Revolution."

The business meeting of the Society will be held following the formal program. Along with reports from Society officers, matters to be discussed will include continuing efforts to obtain MLA affiliated organization status and plans for next year's meeting (place, time, and topic to be determined).

[4]

NEWS ITEMS AND WORK IN PROGRESS

by Stephen Jan Parker

The rising costs of publishing, supplies, and postage have finally caught and surpassed Newsletter revenues. Thus we must increase (modestly) our membership/ subscription rates, the first increase in two years, as follows:

individuals, $4.00 per year

institutions, $5.50 per year

for subscriptions outside the USA add $1.00 per year for postage;

airmail - add $2.00 per year for Canada and Pan Am; $3.00 for Europe.

back issues: $3.00 each for individuals; $4.00 each for institutions.

Numbers 1 and 2 in xerox copy only.

It is our hope that this slight adjustment in rates will not result in subscription/member-ship losses.

*

Volume II of Vladimir Nabokov: Lectures on Literature, devoted to Nabokov's university lectures on Russian authors, is scheduled for release on November 4. A pre-release review of the book can be found in the New York Times Book Review of October 25.

*

[5]

Mrs. Vera Nabokov has provided the following list of Mr. Nabokov's works appearing thus far this year:

1981 releases - King Queen, Knave, Details of a Sunset, Ada, Glory, Look at the Harlequins!, Tyrants Destroyed, Strong Opinions. New York: McGraw-Hill paperbacks.

January 1981 -Feu pale (Pale Fire). tr. Raymond Girard. Paris: Editions Gallimard, collection "L'lmaginaire," paperback.

February 1981 - The Gift. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books paperback.

March 1981 - Tyrants Destroyed and Other Stories. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books paperback.

March 1981 - Regarde, regarde les arlequins! (Look at the Harlequins!). tr. J.B. Blandenier. Paris: Union générale d'éditeurs, serie "Domaine étranger."

April 1981 - Machenka (Mary), tr. Marcelle Sibon. Paris: Librarie Fayard, intro, by Vladimir Nabokov, paperback.

March 1981 - La Invention de Vals (The Waltz Invention), tr. José M. Martinez Monasterio, Barcelona: Plaza & Janes, édition "Rotativa."

April 1981 - L'Exploit (Glory), tr. Maurice Couturier. Paris: Editions Julliard.

May 1981 - tapes: Lolita Gyldendal, in Danish (Lydbger), Denmark. Album 1: 6 cassettes; album II: 5 cassettes, narrator Mogens Boisen.

May 1981 - "The Vane Sisters" in American Tradition in Literature anthology, ed. Georges Perkins. Vol. II. New York: Random House. Idem in shorter edition in one volume.

[6]

May - Glorie, tr. R. Kluphuis. Amsterdam: Elseviers

July - Pale Fire. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books reprint.

July - Transparent Things. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books reprint.

July - Bend Sinister. New York: Time-Life Books, special edition.

*

Phyllis Roth (Dept, of English, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY 12866) is still accepting submissions for Critical Essays on Vladimir Nabokov to be published by G. K. Hall. See the original announcement in VNRN #6 (Spring 1981), p. 4.

Steven Nielsen (Slavic Languages & Literatures, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138) is completing work on his dissertation, The Genesis and the Significance of the Intentionally Deceptive Narrator in Nabokov's Novels.

*

D. Barton Johnson (Department of German & Russian, University of California, Santa Barbara, 93106) writes that he has a number of articles which will soon appear; "Spatial Modeling and Deixis: Nabokov's Invitation to a Beheading," in Poetics Today (Tel Aviv); "The, Scrabble Game in Ada or Taking Nabokov Clitorally," in The Journal of Modern Literature; "The Key to Nabokov's Gift, in Canadian-American Slavic Studies;

*

[7]

"Vladimir Nabokov's Solus Rex and the 'Ultima Thule' Theme," in Slavic Review; "Inverted Reality in Nabokov's Look at the Harlequins!" in Studies in Twentieth Century Literature. He has also submitted for publication two other articles: "The Ambidextrous Universe of Nabokov's Look at the Harlequins!" and Don't Touch My Circles: The Two Worlds of Nabokov's Bend Sinister."

*

According to the program of the upcoming AATSEEL meeting, Marina Astman of Barnard College will read a paper, entitled "Nabokov and America" in the session, "Russian Views of America and American Views of Russia," on December 29.

*

Gavriel Shapiro (601 East Clark St., Apt. 23, Champaign, IL 61820) has recently published an article in Russian, "Russkie literaturnye alliuzii v romane Nabokova Priglashenie na kazn"’ ("Russian Literary Allusions in Nabokov's Invitation to a Beheading"), Russian Literature, IX (1981) 369-378.

*

The newest of Ardis (2901 Heatherway, Ann Arbor, MI 48104) titles on Nabokov is W. W. Rowe's Nabokov's Spectral Dimension, a 1981 release.

*

[8]

In our Spring 1981 issue the abstract of Ellen Pifer's paper, "Wrestling with Doubles in Nabokov's Novels," was incorrectly identified as having been read at the AATSEEL meeting. Actually, Professor Pifer presented the paper at the Houston MLA Convention in the Special Session, "The Double: Patterns in Twentieth Century Literature."

*

On occasion, letters to the Newsletter mention courses being taught on Nabokov. For example, Stephen Fix (English Department, Williams College, Williamstown, MA 01267) writes us that this semester he is co-teaching a seminar on Nabokov and Pynchon. It would be of interest to try to determine the extent and nature of Nabokov studies in colleges and universities in the USA and abroad. Write us with the following information: title/theme of the course; works being read; frequency of course offering; and department in which the course is offered.

*

A sixty minute documentary on the life and work of Vladimir Nabokov, presented by Denis Donoghue, Henry James Professor of English Literature at New York University, with readings from Nabokov's work by James Mason, is in preparation. The program is being produced by Brian Barfield for England's BBC Radio 3 and is scheduled for broadcast this spring.

*

[9]

John DeMoss (Pft. Ed. Ctr., Annex A Box 3, APO NY 09710) has composed a 38 page index to Nabokov's Strong Opinions. He lists key words, proper nouns, subjects, and even some entire quotes, with copious subheadings. His aim, he writes, is to provide a useful index for people, like himself, who have read the book and want to look up some topic or quotation which they remember imperfectly. Mr. DeMoss will be glad to provide a copy to all interested persons at a cost of $4.00 to cover photocopying and airmail postage.

*

Special thanks are due Ms. Paula Oliver and Ms. Cheryl Berry for their assistance in putting together this issue.

[10]

DAVID CRONENBERG: A POSTSCRIPT

by Timothy R. Lucas

(The topic of this year's meeting, "Nabokov … And Others," is timely because it also points to the growing comparativist dimension in Nabokov studies. We find it in numerous articles, dissertations , and in such books as Autobiography and Imagination: Studies in Self-Scrutiny (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981) which examines "the imaginative strategies practiced by James, Yeats, Pasternak, Sartre, Nabokov" and Representation and the Imagination: Beckett, Kafka, Nabokov, and Schoenberg (Chicago University Press, 1981).

Recent correspondence with Timothy Lucas (3160 McHenry Avenue 11, Cincinnati, OH 45211) brings another dimension of "Others" which perhaps fits best under our paraNabokovologie rubric. Mr. Lucas has written an essay on Nabokov's pervasive influence in today's horror film genre. Quoting Joe Dante ("The Howling"): "Nabokov has almost replaced Brecht for this generation of filmmakers. When people went beyond the realm of film, it was called Brechtian. Today, the same thing is Nabokovian." Following below is Mr. Lucas' postscript to his article. SJP)

*

"The Shape of Rage: Filming the New Mythology", an essay of mine published in Heavy Metal's September 1981 issue, puts forth the observation that the major auteurs behind the contemporary horror film are

[11]

influencing the genre with their personal interests in the writings of Vladimir Nabokov. Of course, I realize how absurd and pretentious this may sound; The Howling influenced by Ada?—that's how it sounds; still, it's true, nonetheless.

For the past nine years, I've analyzed the evolution of fantasy films in reviews for Cinefantastique and, over the years, I've noticed some intriguingly Nabokovian touches in the textures of certain films I've seen. When I read Paul M. Sammon's article/inter-view with Canadian director David Cronenberg (They Came From Within, Rabid, The Brood, and Scanners) in Cinefantastique's Spring 1981 issue (Vol. 10 - No. 4, pp. 20 - 35), I was pleased to learn this had been no hallucination on my part; Sammon touched fleetingly on Cronenberg's love of Nabokov, his boyhood interest in lepidoptery, et cetera, several times. So, when the opportunity to interview Cronenberg for Heavy Metal arose, I jumped at the chance to probe this subject more deeply, for my own purposes, and for interested readers of the VNRN.

Portions of the following transcription appear in Heavy Metal (September 1981, pps.73-76).

TRL: In which ways, if any, has Nabokov influenced your work as a film-maker, and as a maker of horror films in particular?

DC: I've just been reading his Lectures on Literature, and remembered how it struck me that Nabokov always said that, after all

[12]

those years spent reinventing' Russia, he found himself faced with the prospect of having to reinvent America. What he meant, of course, is that an artist does not deal with 'Reality' (as it is properly known) but in fact has to reinvent everything. Each work is the invention of a world. That's why, when I say there's no such thing as a realistic film — and I do — I'm really only echoing Nabokov, saying there is no such thing as a realistic novel. The films that played as being "ultra-realistic" some years back, like Marty for example, look so theatrical that they are not, in any sense, realistic. I think movies function best as a dream tale or dream state, and work on dream logic. I like to think of film audiences as members of a Platonic group, sitting around a fire in Plato's cave, dreaming a common dream together as they watch the screen. My film The Brood could be seen as the "nightmare version" of Kramer vs. Kramer. For that reason, in my opinion, it's more realistic. As a film about divorce, The Brood is more realistic in terms of the underlife of the situation. When Kramer goes to sleep at night, he dreams The Brood.

So, in answer to your question, I would say that Nabokov's attitudes really crystallized my own. As for horror films in particular, I'm reminded that Nabokov didn't feel that an artist had any social responsibility, in the sense of preaching a moral. So, when people have asked me, in the past, whether I worry about the effect my films have on children, lately I've been expressing myself in a more Nabokovian way, saying

[13]

that, as a citizen I have a social responsibility and, as a father, I have a social responsibility but, as an artist, I have absolutely no responsibility to anyone.

TRL: Still, more than any other artistic medium, film demands a certain level of commercialism, right?

DC: Yes, this philosophy doesn't translate totally into film. An artist like Nabokov would've been perfectly willing to let Lolita sit on a shelf for 5 or 6 years, if he couldn't find a publisher for it — and not change it. But when you begin taking money from a producer, and you have investors, and you're going to spend $5,000,000 on a movie, it becomes a little dicey. Because, suddenly, you do have responsibilities that don't coincide exactly with …

TRL: With your inspiration. In the end credits of your most recent film Scanners, I noticed a character named Arno Crostic. Was this spurred on by Nabokov's fascination with acrostics and wordplay?

DC: No. I never actually use anagrams, but I — for some reason, a name really says something to me and that's usually the way it is. I would never be as cross-referential as Nabokov is in, say, Ada, where you have such things as dorophones and Silentium motorcycles. The latter was interesting to me because I have some Italian motorcycles, and they have mufflers called "Silentiums". Now that's something for the VNRN!

[14]

TRL: Yet there are some horror film-makers who follow the cross-referrential route—Joe Dante in The Howling, and John Carpenter in Halloween—naming characters after their producers, after characters from classic horror films, who stylistically ape the moves of other directors in hommage.

DC: I don't have any impulse to do that, at all. In a way, these guys have more in common with Nabokov on this point than I do, because I get no pleasure out of setting those things up, or in knowing that they're there. To me, such techniques distract the audience, it prevents them from entering the trance.

TRL: What are your opinions of the films made of Nabokov's novels?

DC: The only one I thought was really good, and it's a very quirky one, was King Queen Knave. Even cinematically, it's very quirky, but I thought this very quality reproduced something of Nabokov that straight guys like Kubrick hadn't been able to reach. I haven't read King, Queen, Knave, so I don't know to what extent the film was faithful, but something about its sense of humor felt very right to me.

I also saw Laughter in the Dark, which wasn't a very successful film. It was transplanted and updated, which drastically altered the feel of it; that bothered me. The film was so bleak; it had absolutely no irony, no humor, no anything. I haven't seen Despair, the Fassbinder film.

[15]

I didn't think Lolita was at all successful, except for James Mason as Humbert Humbert--he was perfect. But I thought it became a bit distracted with the Peter Sellers routines, and I also thought that Sue Lyon was terrible. Not only was she terrible, she was dressed terribly.

TRL: In a time when mainstream films seem hopelessly tied to the same old themes and modes of presentation, do you believe horror films (because of their nature) are any more accessible to structural expansion and experimentation?

DC: Yes, I do. It's harder to experiment in a film without that general tone that says. Anything can happen and you must accept it as being real. That's why I make these films.

[16]

ABSTRACT

"Nabokov's Hermann: Homme sans moeurs et sans religion!"

by David Lowe

(Abstract of the paper presented at the Annual National Meeting of AATSEEL, Houston, December 1980.)

Hermann, the narrator of Nabokov's Despair, is characterized by a peculiar sort of tunnel vision that is both destructive and self-protective. He perceives non-existent similarities and fads to distinguish real ones. Specifically, Hermann, who is obsessed with a false real-life double, Felix, has a genuine fictional double in the person of the mad hero of Pushkin's "Queen of Spades."

Both Hermanns are Russianized Germans. In both protagonists there is a dangerous discrepancy between surface restraint and an unbridled fantasy. For the two Hermanns crime is associated with card playing. Pushkin's Hermann has his ill-earned "three, seven, ace," while Nabokov's hero at one point says: "Let us discuss crime, crime as an art; and card tricks." He goes on to describe the preparations for Felix's murder in the following way: "My accomplishment resembles a game of patience, arranged beforehand; first I put down the open cards in such a manner as to make its success a dead certainty; then I gathered them up in the opposite order and gave the prepared pack to others with the perfect assurance it would come out." In short,

[17]

both players are more than willing to gamble for precariously high stakes as long as they can stack the deck. (The catch, of course, is that neither is playing with a full deck.)

Details surrounding the crimes and preparations for the crimes in the two works overlap. Both Hermanns conduct lengthy clandestine correspondences. In another parallel, berth Hermanns are cast into the role of voyeur at their victims' nocturnal toilette. The most important parallel is an obsession with an utterly mad scheme, the sources for which lie in literature itself. Allied with this obsession is an absence of traditional moral or religious values combined with a cringing superstitiousness.

Because of their overheated imaginations both Hermanns are imprisoned in an illusory reality of their own molding. Significantly, "Queen of Spades" and Despair rely on common imagery having to do with conjuring, dreams, nightmares, mirrors, and reflections. The two protagonists suffer from a metaphorical blindness that causes them to see things that are not there and vice versa.

Is one falling into a Nabokovian trap by drawing parallels between "The Queen of Spades" and Despair? After all, Ardalion, who gives the lie to Hermann's artistic pretensions, says:n"You forget, my good man, that what the artist perceives is, primarily, the difference between things. It is the vulgar who note their resemblance." This paper may then be nothing but vulgar scholarship, but the evidence suggesting a link between Pushkin's story and Nabokov's

[18]

novel is persuasive. And how ironically appropriate it is that in Despair Hermann, so certain of his infinite superiority to those "great and nimble novelists and criminals," so persuaded of the accuracy of his perceptions about literature and life, so convinced that in Felix he has found a double, and so wrong on all counts, should fail as well to discern his mirror reflection in the demented hero of "Queen of Spades."

There is a second Pushkinian moment here as well, and it has to do with Nabokov's Hermann's assertion that he is an artistic genius and that the motivation for his crime is primarily esthetic. Surely somewhere in the- subtext here is Pushkin's "Mozart and Salieri," in which the central question is whether an artistic genius and a murderer can reside in one and the same body. Is Despair Nabokov's attempt to show that a genius can be a murderer? After all, Hermann is a brilliant author, just as he is a cold-blooded murderer. He is also quite, quite insane; and Pushkin's statement of the dilemma leaves, insanity out of the proceedings and argumentation.

Clarence Brown has remarked that Pushkin is Nabokov's muse and Nabokov's fate. Nowhere is that more true than in Despair, where Nabokov gives Pushkin a knowing nod and joins him in the glorious exercise of making high art out of what would seem to be shoddy material.

[19]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

(Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov's works will be to the most recent hardcover U.S. editions.)

Some Remarks on Flaubert and Ada

(In VNRN #5, Fall 1980, pp. 27-28, I rashly asserted that Ada seemed to include only a single direct allusion to Flaubert. Several correspondents corrected me. The most detailed reply came from Finland and appears below.)

Charles Nicol's theory on the alleged dearth of Flaubert-references in Ada may require qualification, for at least one heretofore undetected allusion to that author can be pointed out. The single-sentence paragraph ending Part One, Chapter Forty-three in Van Veen's chronicle is designed as a parody of Flaubert's clipped chapter closings in Madame Bovary, and a specific source appears at the end of Part One, Chapter Nine in the latter text:

When in early September Van Veen left Manhattan for Lute, he was pregnant (Ada, p.345).

[20]

Quand on partit de Tostes, au mois de mars, Mme Bovary était enceinte (Madame Bovary, Paris: Garnier-Flammarion, 1966, p. 101).

In the edition used by Nabokov himself as a teaching copy when lecturing on "Masters of European Fiction" this is rendered as "When they left Tostes in the month of March, Madame Bovary was pregnant" (Madame Bovary, trans. Eleanor Marx Aveling, New York: Rinehart, 1948, p. 69; the text is reproduced in Lectures on Literature, p. 141).

That previous commentators have already glossed this passage as an allusion to expressly Tolstoyan devices (Proffer, "Ada as Wonderland: A Glossary of Allusions to Russian Literature"; Appel, "Ada Described") is due to a characteristic ploy on Nabokov’s part. An overt reference to "a clever pastiche by Ada Veen mimicking Tolstoy’s paragraph rhythm and chapter closings" (p. 343) appears on an adjacent page, and Anna Karenina indeed provides another possible source for the parody (cp. the comment on Kitty Levin's pregnancy closing V: 20). The Tolstoy linkage is pointed out, in addition, in "Notes to Ada" by "Vivian Darkbloom" (Penguin ed., p. 472). Nabokov's allusions in Ada are often multi-referential, and by crossing Flaubert with Tolstoy he has managed to telescope a pertinent observation on the status of his own creation as well: even masters of European fiction duplicate patterns of artifice found in others; no literary text escapes being part of a literary series; and it is to such a

[21]

series that Ada--a composite of intertextual relations--owes its existence.

It appears, then, that Flaubert has more "understudies" than one in Ada, and by multiplying these literary relationships Nabokov has secured the position of the French novelist also in Antiterran annals of literature.

— Pekka Tammi, The Finnish Academy, Helsinki, Finland

A Possible Anti-Source for Ada, or, Did Nabokov Read German Novels?

In "Vstrecha" ("The Reunion"), a story written in December 1931, Nabokov makes passing reference to a German novel on the then "fashionable theme" of incest. Nabokov identifies the author as Leonard Frank (1882-1961), but does not give the title of the book which he terms "philistine tripe." The novel is Leonard Frank's notorious 1929 Bruder und Schwester (Miinchen, 1953; in English as Brother and Sister, New York, 1930), which deals with the incestuous passion and marriage of fabulously wealthy, polyglot, cosmopolitan siblings who, after the death of their parents, live happily ever after. Although the plot of the novel differs quite substantially from that of Ada, it nevertheless contains a number of scenes and details which (perhaps by chance) parallel those in Nabokov's 1969 chef-d'oeuvre. Frank, a quondam best-selling author who has been termed "a vulgarisator of expressionism," writes an overwrought prose that must have afforded Nabokov

[22]

considerable amusement if he actually read the work that he alludes to. A sample: "Her mouth opened soft to his firm lips; they slipped down into the chasm of her wild and fainting surrender, which inflamed him ever afresh to the verge of madness" (p. 59). If indeed the forgotten Frank novel is one of the subtexts of Ada, it must certainly be accounted as a negative one.

But did Nabokov read the novel or was the reference hearsay? In his Foreword to the English translation of the 1928 King, Queen, Knave Nabokov asserts, "I spoke no German, had no German friends, had not read a single German novel either in the original or in translation." Although Ada itself, in spite of its plethora of literary allusions to brother-sister incest (especially Chateaubriand and Byron), contains no overt reference to Frank's book, Nabokov's 1930 Zashchita Luzhina (The Defense) does display a curious parallel. Compare the following passages:

(Luzhin) stopped stock-still in front of a stationery store where the wax dummy of a man with two faces, one sad and the other joyful, was throwing open his jacket alternately to left and right: the fountain pen clipped into the left pocket of his white waistcoat had sprinkled the whiteness with ink, while on the right was the pen that never ran (The Defense, p. 204).

All the shop windows were now illuminated ... and a life-sized wax figure, a Ulan with two heads, one face cheerful

[23]

and one bitterly aggrieved, constantly drew aside the lapels of his coat, showing first a pique waistcoat stained with ink, and then — beaming — the other side, snow-white, because the fountain-pen in the pocket was of a nonleaking sort (Brother and Sister, p. 48).

Given the publication dates it is tempting to assume that Nabokov borrowed the image, thus contradicting his above statement about his innocence of German novels and implying firsthand familiarity with Frank’s novel. (The 1930 publication date of the English translation of Frank's work is too late for it — rather than the German text — to be a probable source.) Alas, the case is not as clear-cut as one would wish. Judging by contemporary German reviews, Frank's book appeared in late 1929. The Defense, although published in book form in 1930, was serialized in Sovremennye Zapiski starting in the last issue of 1929 (#40) and extending into issues 41 and 42 in 1930. The scene with the wax dummy is in the final instalment — presumably well after the appearance of Frank's novel. The crucial issue, however, is the date of the composition of the scene and that remains unknown. Thus the publication dates do not rule out the possibility of a borrowing, but neither do they support it. Further, both Nabokov and Frank lived in Berlin in the late twenties and it is quite possible that the figure of the wax dummy which apparently stood in a shop window in Friedrichstrasse was noticed by both authors and was incorporated into their current novels.

[24]

The whole matter may be a web of coincidences, but the coincidence seems a bit forced given Nabokov's reference to Frank's novel of incest in his 1931 short story and the suggestive, albeit inconclusive, parallels between Frank's Вruder und Schwester and Nabokov's Ada.

—D. Barton Johnson, University of California at Santa Barbara

[25]

From a Family Album

The photographs on this and the following pages were taken circa 1897. They were found by a friend of the Nabokov's in an old family album kept in a small museum in the village of Rozhestvenn. They have been provided to the Newsletter by Hélène Sikorski-Nabokov, Vladimir Nabokov's sister. They have never been reproduced in any publication.

[26-27]

Photo #1. Mushrooms, Vyra Estate. Right to left: Olga Nikolaevna Rukavishnikov (VN's maternal grandmother); Elena Ivanovna Nabokov (VN’s mother), not yet married at this time; two unidentified ladies.

"One of [Mother's] greatest pleasures in summer was the very Russian sport of hodi’1 po gribi (looking for mushrooms). ... As often happened at the end of a rainy day, the sun might cast a lurid gleam just before setting, and there, on the damp round table, her mushrooms would lie, very colorful, some bearing traces of extraneous vegetation—a grass blade sticking to a viscid fawn cap, or moss still clothing the bulbous base of a dark stippled stem. And a tiny looper caterpillar would be there, too, measuring, like a child's finger and thumb, the rim of the table, and every now and then stretching upward to grope, in vain, for the shrub from which it had been dislodged."

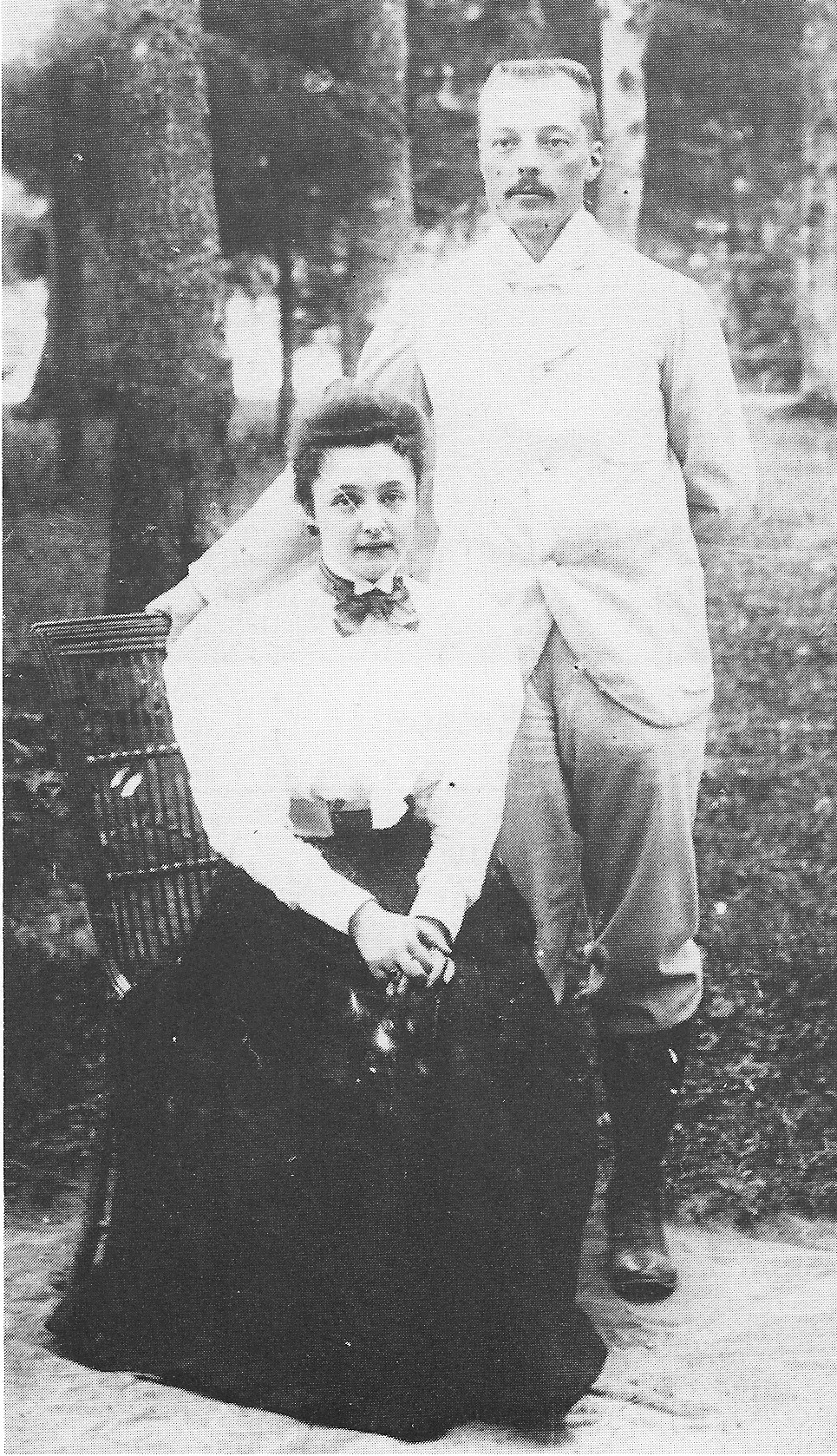

Photo #2. VN's Parents, Vyra Estate.

"Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, jurist, publicist and statesman, son of Dmitri Nikolaevich Nabokov, Minister of Justice, and Baroness Maria von Korff, was born on July 20, 1870, at Tsarskoe Selo

[30]

near St. Petersburg, and was killed by an assassin's bullet on March 28, 1922 in Berlin.

... On November 14 ( a date scrupulously celebrated every subsequent year in our anniversary conscious family) 1897, he married Elena Ivanovna Rukavishnikov, the twenty-one- year- old daughter of a country neighbor with whom he had six children (the first a stillborn boy)." (SM, 173-74)."My Mother, Elena Ivanovna (August 29, 1876-May 2, 1939), was the daughter of Ivan Vasilievich Rukavishnikov (1841-1901), landowner, justice of the peace, and philanthropist, son of a millionaire industrialist, and Olga Nikolaevna (1845-1901), daughter of Dr. Kozlov." (SM, 66).

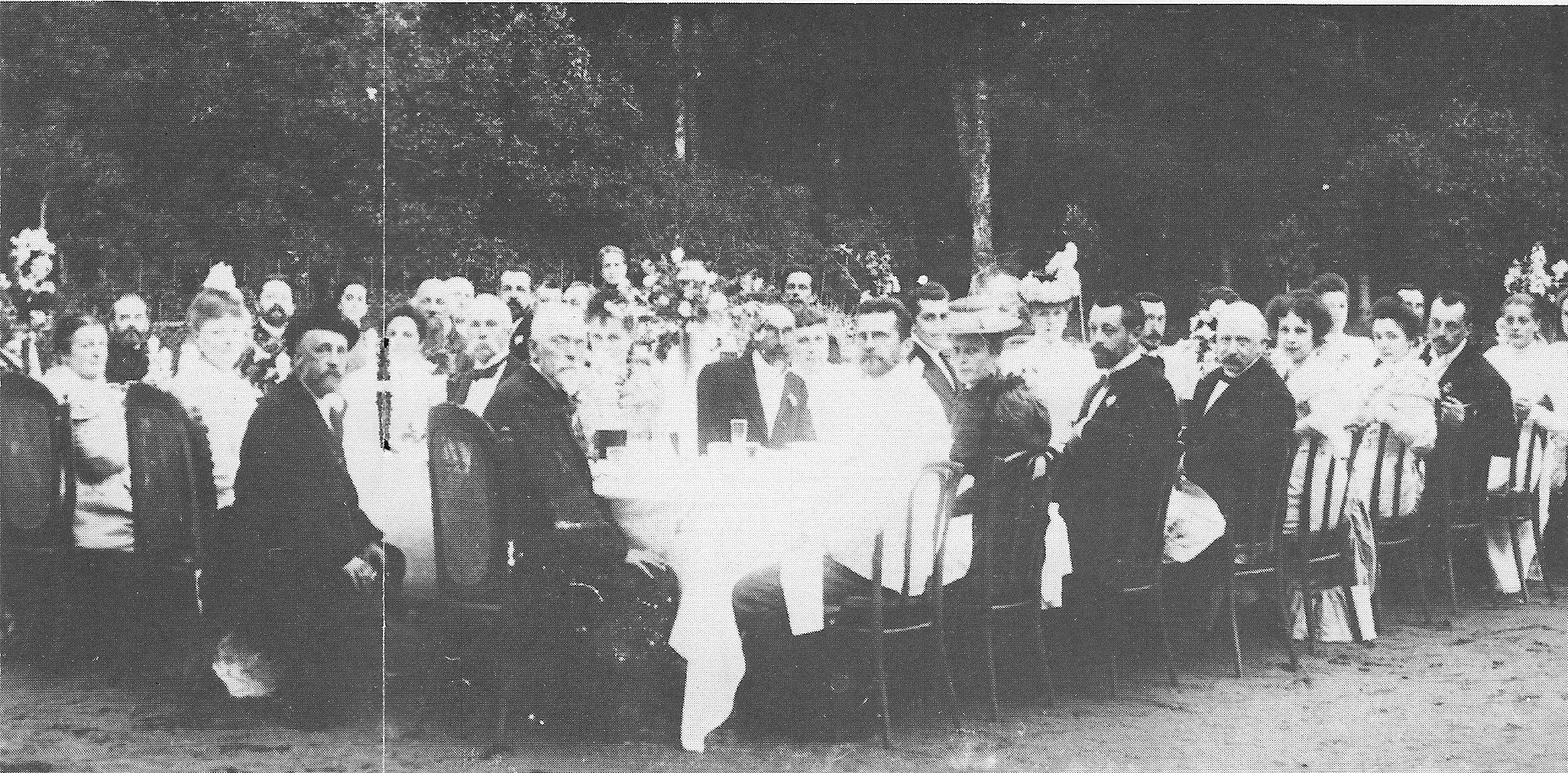

Photo #3: Engagement Dinner, Summer.

VN's father, second from the right, is leaning on the back of his chair. Next to him, on his left, his young fiancé, VN's mother. From left to right: VN’s maternal grandmother, his paternal grandmother, and his maternal grandfather. The others are paternal aunts and guests.

Photo #4: Bicyclists. Left to right: Vasilij Ivanovich Rukavishnikov ("Uncle Ruka," VN's maternal uncle); VN’s father and mother; unidentified lady; Elizaveta Dmitrievna (later married to Prince Heinrich Sayn Wittgenstein); unidentified gentleman; Natalia Dmitrievna Peterson, née Nabokov, and her

[31]

son Dmitri. Both ladies in white are VN's paternal aunts.

". . . there was the linden tree marking the spot, the side of the road that sloped up toward the village of Gryazno (accented on the ultima), at the steepest bit where one preferred to take one's "bike by the horns" (bika za roga) as my father, a dedicated cyclist, liked to say, and where he had proposed" (SM, 40).

*

"Uncle Ruka appeared to me in my childhood to belong to a world of toys, gay picture books, and cherry trees laden with glossy black fruit. ... I remember him as a slender, neat little man with a dusky complexion, gray-green eyes flecked with rust, a dark, bushy mustache, and a mobile Adam's apple bobbing conspicuously above the opal and gold snake ring that held the knot of his tie . . . and there was usually a carnation in the buttonhole of his dove-gray, mouse-gray or silver-gray summer suit." (SM, 68-69).

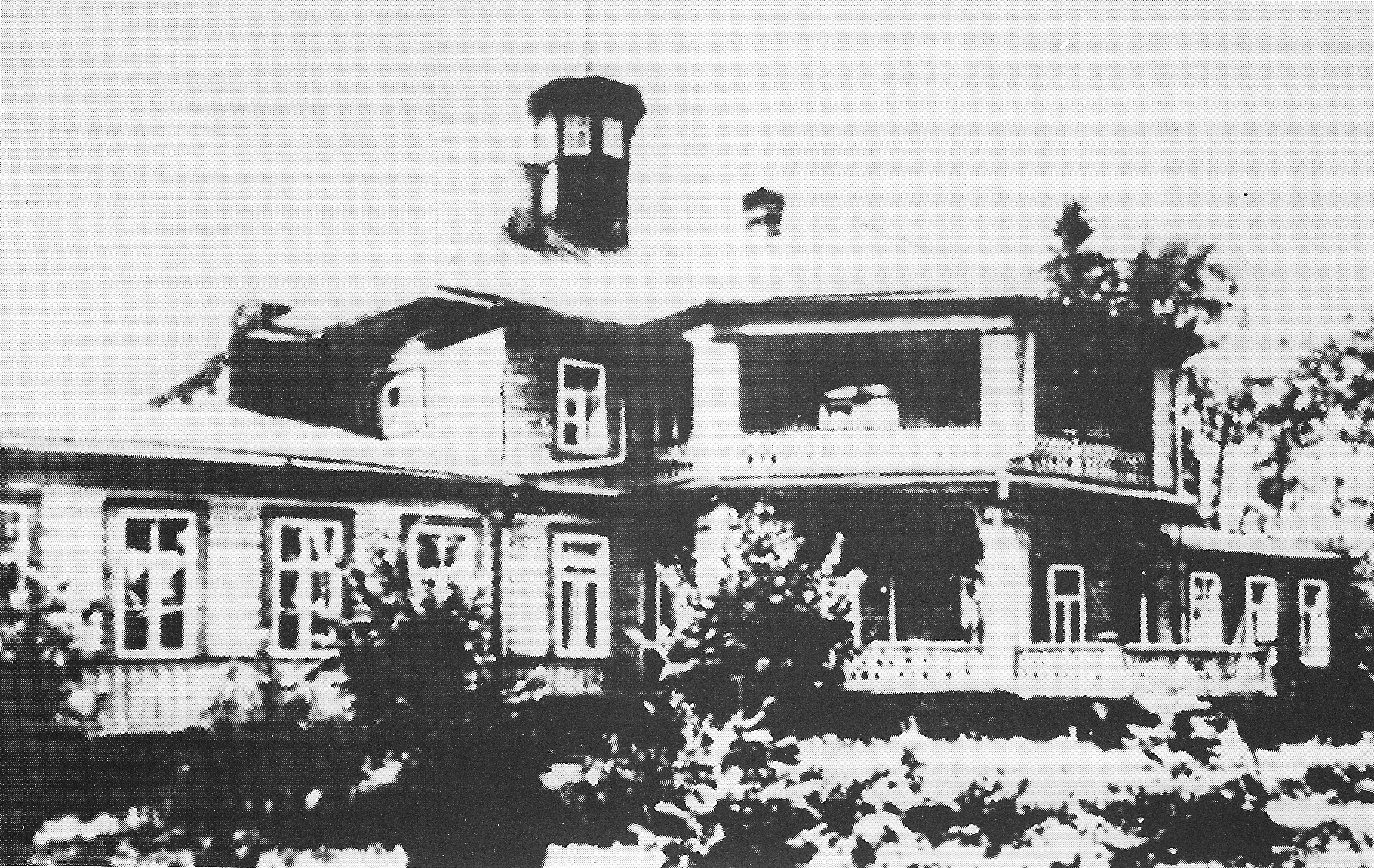

Photo #5: Batovo Estate House.

"The estate of Batovo enters history in 1805 when it becomes the property of Anastasia Matveevna Rïleev, born Essen. Her son, Kondratiy Fyodorovich Rïleev (1795-1826), minor poet, journalist, and famous Decembrist, spent most

[32]

of his summers in the region .... the Rïleev pistol duel with Pushkin, of which so little is known, took place in the Batovo park between May 5 and 9 (Old Style), 1820. … Batovo was acquired from the state by my paternal grandmother's mother, Nina Aleksandrovna Shishkov, later Baroness von Korff, from whom my grandfather purchased it around 1855." (SM, 61-62).

[33]

ABSTRACT

"Nabokov's Lolita and Pushkin's Onegin: A Colloquy of Muses"

by Priscilla Meyer Wesleyan University

(Abstract of an article in progress)

Nabokov was working on his 4 volume translation and commentary of Eugene Onegin in the 1950's at the same time as he was writing Lolita. Yet in that novel full of literary references, he never once alludes directly to Onegin, a novel which might be said to be the most important single monument in Nabokov's literary canon.

I propose that Nabokov set himself the task of creating a 20th century equivalent to Onegin, a novel which would resituate the notions of "high" and "low," of "popular" and "elite" in order to create a contemporary realism, just as Pushkin overturned the tenets of Romanticism 100 years earlier.

The main characters of the novels may readily be paired:

Lensky the foolish young German romantic who dies in a duel with Onegin, the cold hero, is analogous to Quilty, the pornographer who is shot by Humbert. The crime committed by both, in the authors' views, is of having murdered the artistic ideals each author cherishes and embodies in his novel.

[34]

Central to my discussion are, of course, the heroines — Tatyana and Lolita (note the congruent sounds). They are the heroines of tragic love stories, but the plot line is, interestingly, merely the metaphorical level of both novels. Their "real" function is as their author's muse, and this is the heart of the matter: Pushkin and Nabokov provide a critique of their cultures and a direction for a "true" aesthetic through the new syntheses of cultural components available to the heroine-muses. My article will show the congruence of Pushkin's and Nabokov's view of art: their novels imply a "naive reader: who collapses art into a True Love version of reality through sentimental projection, a trivialization which leads to tragedy.

The interrelation ship of the two novels provides an illuminating reading of each, as well as a literary confession de foi not made as fully or explicitly by either author elsewhere .

[35]

ABSTRACT

"Cosmic Synchronization and Other Worlds in the Work of Vladimir Nabokov"

by Jonathan Borden Sisson

(Abstract of Dissertation for the award of Ph. D., University of Minnesota, 1979.)

Vladimir Nabokov's concept of "cosmic" synchronization," defined in his autobiography Speak, Memory (1951), offers a principle for a comprehensive understanding of his work, especially of the fruition of his vision in his last four hovels. Cosmic synchronization is the system of all interrelationships within the universe. Awareness of cosmic synchronization is simulated by the creation of an illusion of' a simultaneous perception of all phenomena throughout the universe. A poem, short story, novel, or chess problem may stimulate in the reader this perceptual illusion and its consequent "aesthetic bliss," and Nabokov suggests such an expansionary vision by frequently implying the operation of apparently acausal physical laws unknown at present. He furthermore posits a transcendental vision of an ultimate "something else" that may be perceived intuitively by the mind receptive to a significant pattern of clues in the immediate environment.

As simulation of the greater comprehension of cosmic synchronization, Nabokov uses several devices that recur throughout his work. Three primary devices are the catalogue of remote activity, the juxtapos-

[36]

ition of contrasting images , and the metaphor of metamorphosis. The additional use of "overlapping" images of conflation suggests acausal coincidental relationships and creates an effect of simultaneity of imagery necessary to a vision of cosmic synchronization. In order to liberate the mind from ordinary logical axioms, as preparation for awareness of cosmic synchronization, Nabokov sometimes creates alternative realities: contrasting environments or situations that function simultaneously and yet appear to be mutually exclusive. For example, both the narrator of "Terra Incognita" (1931) and the reader cannot determine whether the story takes place in a jungle or in a bedroom in a city. Alternative realities of variously different kinds occur in the fiction of Nathaniel Hawthorne , Henry James, and H. G. Wells. Wells's works, furthermore, contain significant precursory elements illuminative of Nabokov's works.

In his last four novels — Pale Fire (1962), Ada (1969), Transparent Things (1972), and Look at the Harlequins! (1974) — Nabokov provides four conjectural models of "other worlds." Pale Fire, in contrast to Nabokov's unfinished novel Solus Rex (1940, 1942), offers alternative realities: the disturbed narrator Charles Kinbote appears to be deluded in his belief that he is the exiled king of Zembla, but, despite his unreliability, he may actually be the king of Zembla. Pale Fire also develops the theme of cosmic s yn chronization and transcendent perception of another world entered by John Shade during a stroke. Ada delineates the discrepancies between the

[37]

two almost parallel worlds of Terra and Demonia (Antiterra): because some Demonians share glimpses of a mysterious other world called Terra, which seems to be our Earth, the reader experiences not a typical search for another world but the helpless frustration of observing limited minds struggling to perceive a world obvious to the reader. Transparent Things, narrated from the point of view of ghosts who can intervene in the world of the living, describes another world ordinarily unperceived, with intense devices of cosmic synchronization. Look at the Harlequins! also portrays the interpenetration of two almost parallel worlds: the narrator-novelist, in his life and in his works, parodies Nabokov unwittingly , but he occasionally encounters the world of Nabokov, which, like Terra in Ada, is familiar to the reader; finally the narrator suffers a seizure that enables him to travel into another world. All these conjectural other worlds stimulate the reader to a transcendence of ordinary perception and logic, as a precondition for the greater awareness of cosmic synchronization.

[38]

ABSTRACT

The Intimacy of Imagination: A Study of the Self in Nabokov's English Novels

by Nancy Garfinkel

(Abstract of dissertation submitted for the award of Ph.D., SUNY at Buffalo, 1980.)

My dissertation is a chronological study of Vladimir Nabokov's English novels. Beginning with the thesis that Nabokov's status as émigré — his loss of fatherland and mothertongue — is a metaphor for other more internal and profound psychological displacements, I consider the process of replacing geography and language with art.

Beginning with The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, I explore the relationships between the themes of identity and loss of self; 'artifice' and 'reason'; and intimacy and distance. I show how Nabokov turns apparent paradox into a kind of linear (or 'spiralled') rhetoric. The primary focus of the work is an exploration of Nabokov's search for and discovery of self through the private metaphysics of his novels. I trace the dramatic overlay of theme, narrative style, characterization, and particular characters from one novel to the next. My claim is that of the eight English novels there are only really six 'novelistic' novels, Ada being the last. Transparent Things, the penultimate of the English oeuvre, addresses the relationship between reader and author.' Look at the Harlequins!, the final novel, is concerned with the self-reflexive, inverted

[39]

solipsism inherent in the relationship between the author and his narrator — in short, between the author and himself. In this final work, the original displacements find their finish in the total disregard for any reader: it is a self-sufficient and impenetrable defense against any further possible loss.