Download PDF of Number 9 (Fall 1982) Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter

THE VLADIMIR NABOKOV

RESEARCH NEWSLETTER

Number 9 Fall 1982

______________________________________________

CONTENTS

News Items and Work in Progress

by Stephen Jan Parker 4

Notes From a Descriptive Bibliography (continued),

by Michael Juliar 14

Abstract: Paul Bennett Morgan,

"The Use of Female Characters in the Fiction of V. Nabokov"

(M.A. Thesis) 26

Nabokov in Literatura na Swiecie (Poland)

by Leszek Engelking 30

Annotations & Queries by Charles Nicol

Contributors: Gene Barabtarlo, Ronald E. Peterson,

D. Barton Johnson 34

1982 Nabokov Bibliography by Stephen Jan Parker

Contributor: Paul Bennett Morgan 43

VNRN Institutional Subscribers 53

Reminder 56

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 9, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

[4]

NEWS ITEMS AND WORK IN PROGRESS

by Stephen Jan Parker

The Vladimir Nabokov Society is meeting in two locales this year. On December 28 there will be a Nabokov section in conjunction with the annual convention of AATSEEL in Chicago —1:15-3:15 p.m., in the Florentine Room of the American Congress Hotel, 521 South Michigan Avenue. Samuel Schuman will serve as moderator for a panel on the topic, "Vladimir Nabokov: Aesthete and/or Humanist." Panelists will include Patricia Bruckmann, Lawrence Lee, Priscilla Meyer, and Charles Ross.

On December 30, there will be a Special Session on Nabokov in conjunction with the annual MLA Convention in Los Angeles, from 10:15-11:30 am, in the Los Cerritos Room of the Westin Bonaventure Hotel (Fifth and Figueroa Streets). D. Barton Johnson will serve as discussion leader on the topic, "The Role of Games in Nabokov." Participants will include Janet Gezari, Charles Nicol, Stephen Parker and Earl Sampson. The business meeting of the Vladimir Nabokov Society will follow the session program. One item of business will be the election of Society officers.

*

Mrs. Vera Nabokov has provided the following list of Mr. Nabokov's works appearing March - September 1982:

[5]

March 1982 — Lolita, tr. E. H. Kahane. Paris: Gallimard, Folio paperback.

March 1982 — Une Beauté Russe (A Russian Beauty), tr. Gerard-Henri Durand. Paris: Julliard, no. 2045 paperback.

April 1982 — Elements of Fiction, eds. Robert Scholes and Rosemary Sullivan. Toronto, Canada: Oxford University Press; includes a reprint of "A Visit to the Museum."

May 1982 — Anya v strane chudes' (Alice in Wonderland), by Lewis Carroll. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Ardis; edition of VN's translation, illustrations by John Tenniel.

May 1982 — Machenka (Mary), tr. Marcelle Sibon. Paris: Fayard, edition "Point."

June 1982— Speak, Memory. Harmonds-worth, England: Penguin paperback.

July 1982 — Lolita, tr. Bruno Oddera, intro. Pietro Citati. "Club Italiano die Lettori."

July 1982 — Nabokov's Fifth Arc, eds. J. E. Rivers & Charles Nicol. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press; contains "Notes by Vivian Darkbloom: Notes to "ADA."

July 1982 — Sieh doch die Harlekins! (Look at the Harlequins!), tr. Uwe Friesel. Hamburg, West Germany: Rowohlt, "Deutsche Buch-Gemeinschaft."

[6]

July 1982 — Laughter in the Dark. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin paperback.

August 1982 — La Meprise (Despair), tr. Marcel Stora. Paris: Gallimard, Folio paperback.

August-September 1982— "Details of a Sunset" in Illustrarione Italiana, Nuova Serie Anno II, No. 6.

September 1982 — Anya v strane chudes'. Ann Arbor: Ardis. Exact reproduction of first edition, 1923.

September 1982 — "Fruhling in Fialta" (Spring in Fialta), tr. Dieter Zimmer. Hamburg: Rowohlt rororo paperback.

*

Cornell University, where VN taught for ten years, will devote a number of occasions during the current academic year to honoring his work and his association with Cornell. Preliminary plans include a series of lectures by writers influenced by Nabokov; a series of scholarly talks; and a round-table presentation of recollections by persons who knew him during his Cornell years. There will also be an extensive library exhibit of Nabokoviana pertinent to his Cornell years. For further information contact Professor George Gibian (Department of Russian Literature, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853).

*

[7]

Michael Juliar (74 Kings Road, Little Silver, NJ 07739) is bringing to completion his comprehensive descriptive bibliography of Nabokov's writings, a publication which will be of immense interest and use to all Nabokovphiles, whether teachers, writers, book collectors, or readers. His continuing "Notes From a Descriptive Bibliography" appear in this issue.

*

Valerie Burling (Le Mesnil au Grain, 14260 Aunay-sur-Odon, France) is working on a doctoral thesis entitled "Vision(s) dans l'lmage du Reel: une Lecture des Romans Anglais de Vladimir Nabokov" at the Université de Caen, France.

*

Vimala Ramarao (216 Richards Hall, Harvard University, Cambridge MA 02138) is on a Fulbright grant this year, completing her Ph.D. dissertation, "Self-Consciousness in the Later English Novels of Vladimir Nabokov and its Influence on the Technique," for Bangalore University, India.

*

Dorothea Kiehne-Obuch (Schwetzinger-str. 70, 6909 Walldorf, West Germany) is preparing a study of the contribution to the history of literature which Nabokov made in his Lectures on Russian Literature, entitled

[8]

"Der literarhistorische Aspekt in Vladimir Nabokovs 'Lectures on Russian Literature.'"

*

Ardis (2901 Heatherway, Ann Arbor, MI 48104) announces the publication of A Nabokov Who's Who. A Complete Guide to Characters and Proper Names in the Works of Vladimir Nabokov in April 1983.

The hour-long radio documentary on VN's life and works, edited by Brian Barfield and announced in VNRN #7, was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on March 17. The program will be repeated sometime in the near future.

*

The Journal of the New York Entomological Society (No. 1, March 1982) carries "Vladimir Nabokov 1899-1977: a note on a late entomologist" by Michael Juliar.

*

It is always of special interest to learn of Nabokov related activities in Eastern Europe. Thus Leszek Engelking's summary of Nabokov publications in Poland, which appears elsewhere in this issue, is of particular note. Along with his detailed sum-

[9]

marу, Mr. Engelking also sends along a query. In chapter two of Invitation to a Beheading there is the following fragment: "Childhood on suburban lawns. They played ball, pig, daddy-longlegs, leapfrog, rump-berry, poke." (In Russian: "Igrali v miach, v svin'iu, v karamoru, v chekhardu, v malinu, v tych' … ") In trying to render a Polish translation, Mr. Engelking has been able to adduce the meanings of "ball," "pig," and "leapfrog," but not of "daddy-longlegs," "rumpberry," and "poke." Are these Nabokov's inventions, he wonders? Or do such games exist? Any responses to this query should be sent to the editor.

*

The call for information on Nabokov studies in colleges and universities (VNRN #7) has brought a number of responses which begin to suggest their extent and nature.

Renate Hof (Amerika-Institut der Universität Munchen) writes: "The first course to be given at Munich University was given by Prof. Werner von Koppenfels (English Institute) in 1977. The scope of the course encompassed Bend Sinister, Lolita and Pale Fire. I gave a course last year containing The Eye, Bend Sinister, Lolita and Transparent Things. This course was held at the American Institute. During the winter semester '81-'82 Frau Prof. Doring-Smirnow held a course on The Gift at the Slavic Institute. Furthermore, it might be interesting for you to know that, as far as I know,

[10]

the first seminar held about Nabokov in Germany was given by Prof. Bernd Ostendorf in 1969-'70 at Freiburg University."

Word from France comes from Professor Maurice Couturier (Faculté des lettres, Université de Nice). He estimates that Nabokov is being taught in about half of the French universities, and informs us that André le Vot of the Université de Sorbonne-Nouvelle was one of the pioneers of Nabokov studies in France. Prof. Couturier teaches on Lolita and Alice in Wonderland in his M.A. seminar at the Université de Nice. He mentions that he was prevented from teaching Lolita while he was at the Sorbonne "on the ground that 'ça pourrait choquer les jeunes filles.'"

Don Stanley, our sole respondent from Canada (Vancouver, B.C.), "tutor [s] a course in American literature for the provincial government's Open Learning Institute, which runs a distance learning program throughout British Columbia. We recently revised the course and added a unit on Lolita: We're using the edition with Alfred Appel's devoted annotations, and we hope to include a tape of Nabokov reading the Quilty murder scene. I thought you'd be amused to know that a question on the assignment for the unit quotes the topic of your 'Call for Panel Participants' (VNRN #8) and asks the student to imagine himself in Chicago, choosing sides."

Responses from throughout the USA indicate that Nabokov's works, as one might expect, are on the curricula of numerous

[11]

colleges and universities, in both English and Slavic department course offerings. Lolita, Pale Fire and Pnin are the texts most usually incorporated into English department courses; the earlier stories and novels, in Slavic department courses. Susan Vander Closter incorporates various Nabokov texts into her courses at Virginia Intermont College; Dale Peterson offers a seminar on VN and a colloqium on Borges and VN at Amherst; Stephen Fix со-teaches on VN and Pyncheon at Williams College; Robert Bowie integrates VN texts into his Russian literature courses at Miami University (Ohio), as does Marina Astman in her courses at Barnard College/Columbia University Here at the University of Kansas, VN’s works are taught in a number of courses in both the English and Slavic Departments, and recently a graduate seminar was offered on VN's short stories in the Slavic department.

Readers are requested to please continue to send in such information.

*

D. Barton Johnson (Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of California, Santa Barbara 93106) has recently completed work on two articles: "The Labyrinth of Incest in Nabokov's Ada" and "Text and Pre-Text in Nabokov's Defense." He sends along the following item: "A bit of para-Nabokoviana is to be found in the latest novel of the recently exiled writer Vasily Aksyonov —widely regarded as the best Russian novelist of his generation (b. 1932).

[12]

In his 1981 political thriller Ostrov Krym 'The Isle of Crimea,' the Crimean peninsula has been transmuted into the island home of the White forces who evacuated the mainland at the end of the Civil War. It is an affluent, bourgeois democracy that after sixty years of independence offers itself up to Mother Russia — with disastrous consequences. The Nabokov family, themselves Crimean exiles, are mentioned twice. Early in the novel the hero, Andrei Luchnikov, reflects on the savagery of some of the Whites (as well as the Reds) and mentions the assassination of Nabokov's father (pp.16-17). One of the last scenes is set in the island-country's 'literary restaurant' which is appropriately named 'The Nabokov' (pp. 291-297)."

*

The VNRN is now included in all standard listings of periodicals and newsletters. It has been reviewed favorably in the USA and abroad, and is searched annually for inclusion in the MLA Bibliography, American Literary Scholarship Annual, and the Journal of Modern Literature Review Issue.

*

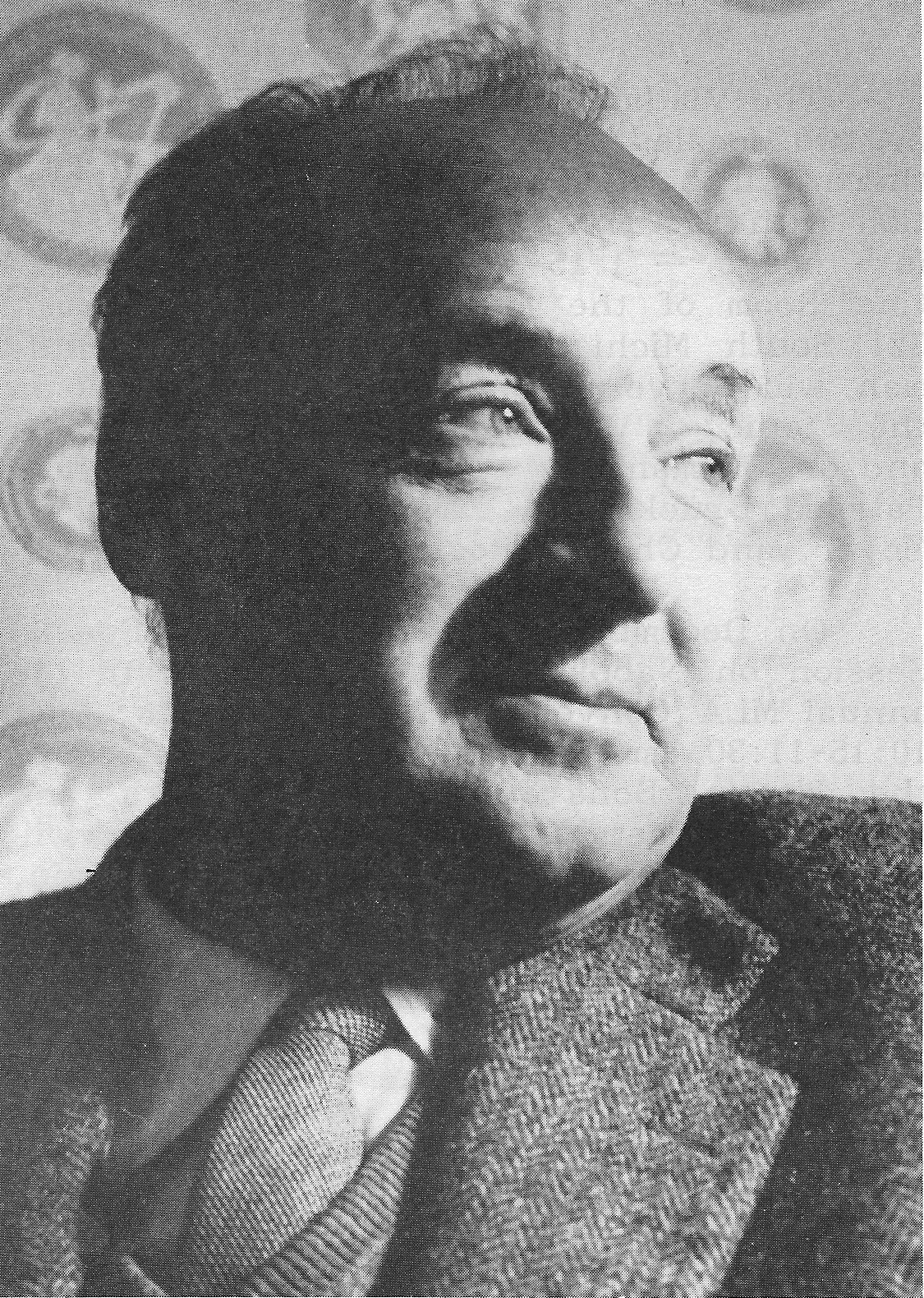

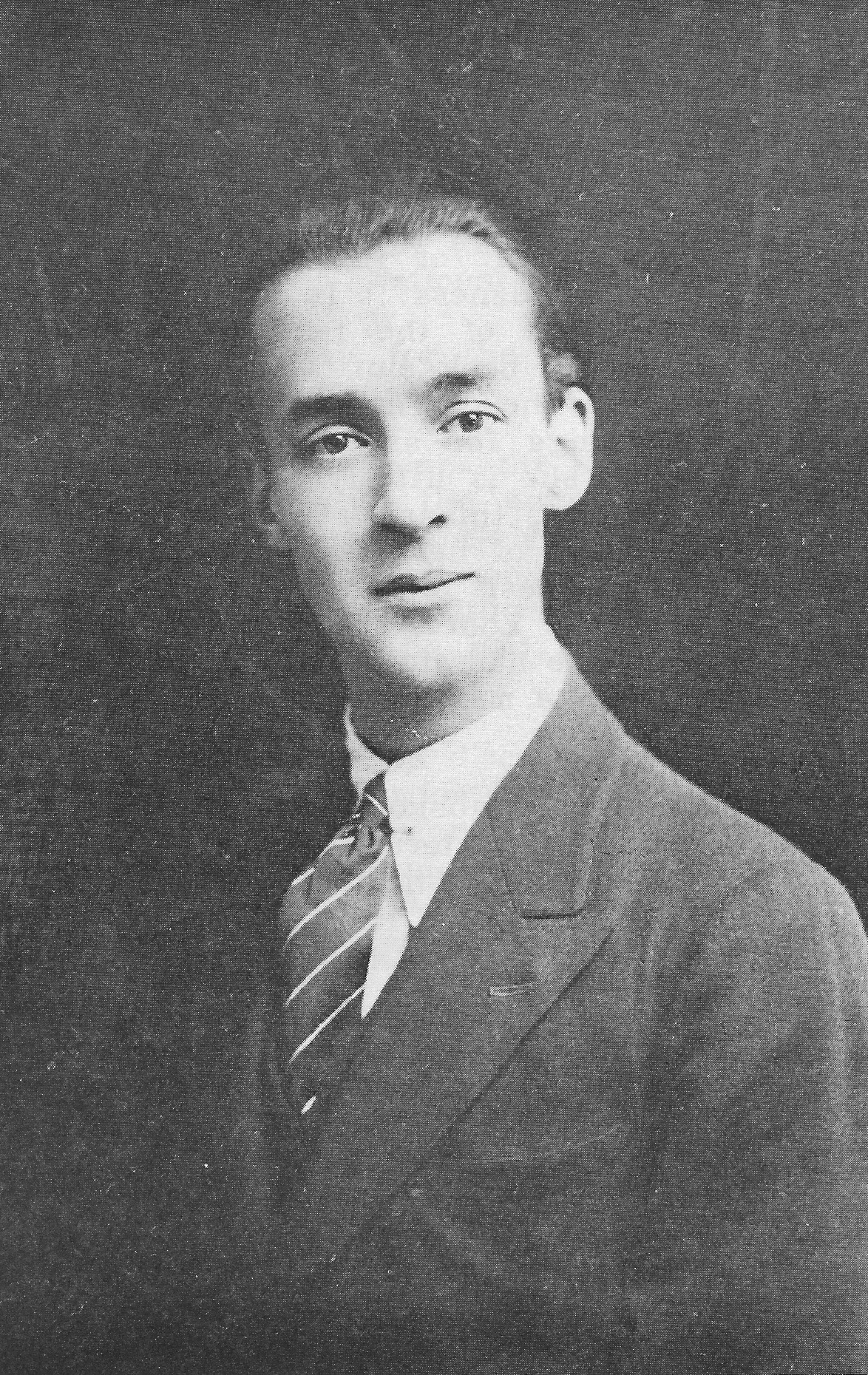

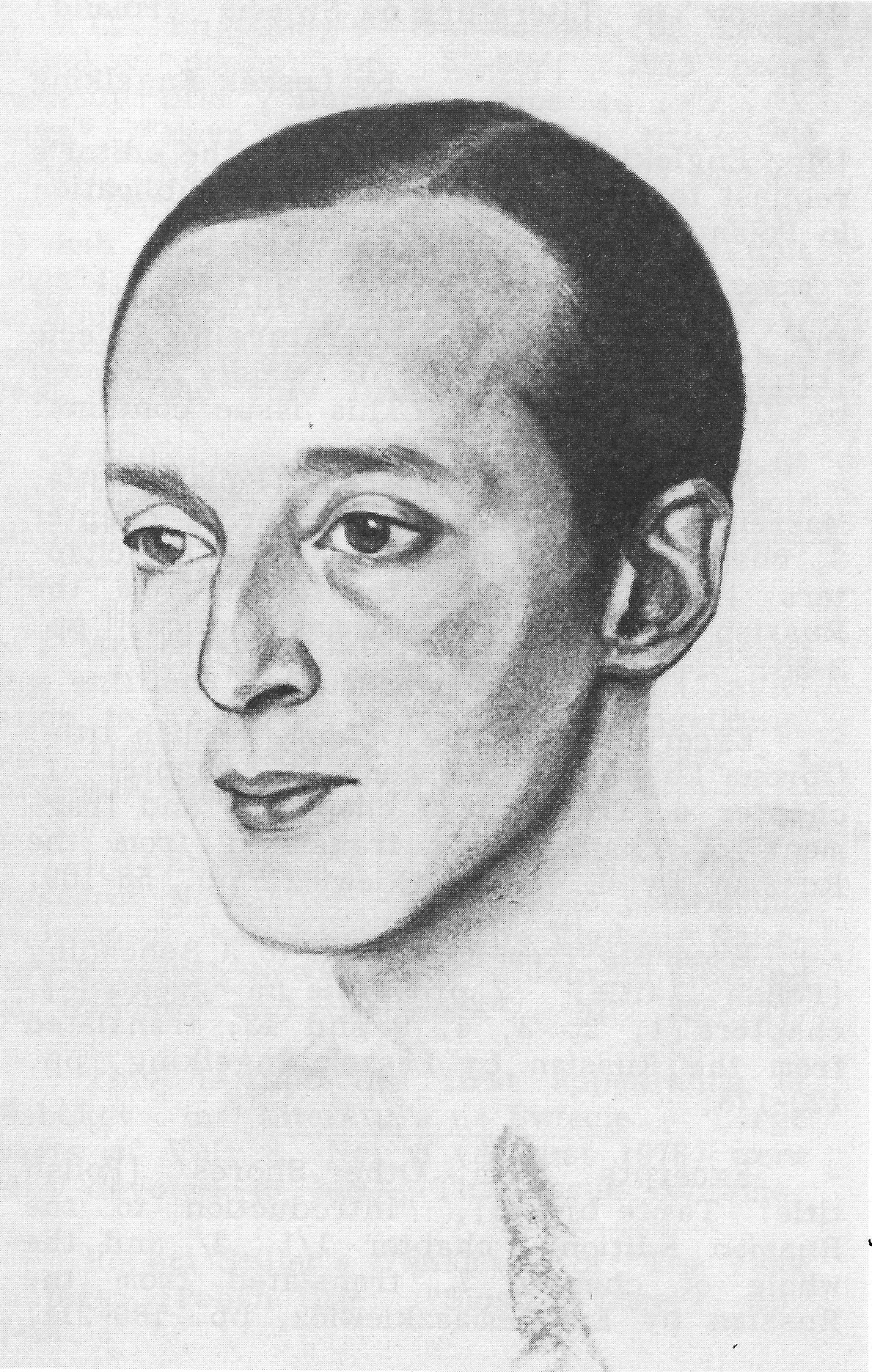

The photographs which appear in this issue were provided by Mrs. Vera Nabokov. The portrait reproduced on page 29 was done by Magda Nahman-Acharia, Berlin, 1933.

*

[13]

Our very special thanks to Ms. Paula Oliver for her help in putting together this issue.

[14]

Notes from a Descriptive Bibliography (continued)

by Michael Juliar

ITEM 3

An incomplete chronology of publication of Vladimir Nabokov's major Russian works in Europe during the 20's and early 30's could be something like the following:

1922 Nikolka Persik

1923 Gornii put'

1923 Grozd'

1923 Ania v strane chudes'

1926 Mashen'ka

1928 Korol' dama valet

1930 Zashchita Luzhina

1930 Vozvrashchenie Chorba

This chronology, based on Field's modest bibliographic research, causes the casual peruser to make three temporal assumptions about Nabokov books, Nabokov literary works, and Nabokov compositions:

1) That the date on the title page of a book was the year in which the book was first published, put on sale, and made available to the Russian émigré public. That is how the above listing was prepared. It is inaccurate.

2) That this publication date was the moment when the work was first set before Russian readers' eyes and signalled the critics that it was open-season on the work. This is a distortion of

[15]

how part of the Russian literary scene functioned.

3) That publication in book form followed soon after Nabokov completed the work's composition. The exceptions to this are well known: Sogliadatai (completed in 1930, published in a book in 1938); Otchaianie (completed in 1932, published in a book in 1936); Priglashenie na kazn' (completed in 1934, published in a book in 1938); Dar (completed in 1937, published in a book in 1952).

There is no more to be said on point three. But there is much of interest in the first two.

Publication Dates

There is no standard source for the publication dates of books published during the Russian emigration in Europe in the 1920's and 30's. Dates can be garnered only through advertisements, new book listings and book reviews in contemporary newspapers . One outstanding source, and the one which I have relied on here, is Rui', the Berlin Russian-language newspaper which published Tuesday through Sunday, from mid-November (probably 17 November) 1920 to 13 October 1931.

Rul's Sunday edition was bathed in literature. By the middle twenties, ads from the émigré publishing houses and bookstores announcing new books and classics, scholarly and literary works, filled many pages. A

[16]

book review page, "Kritika i bibliografia" ["Criticism and bibliography"], and a column, "Literaturnyia zametki" ["Literary notes"], both of which Nabokov contributed to, appeared regularly. New books in Russian, or in other languages but of special interest to the émigré community, were reviewed or listed.

So, it is possible, while winding one's way through a blur of microfilm pages, to watch for the Slovo ad, the "Novyia knigi" ["New books"] listing, or the Savel'ev review of a new Sirin work to get an idea when the book was issued. Reviews or listings could, however, in the ambling course of journal-istic/literary events, appear weeks after the book first came out.

But publishing houses and bookstores want to waste no time in getting their product before the public and cash returned on their investment. Ads, therefore, are among the best clues to when a book was published. Grani and Gamaiun placed ads. Slovo, the publisher of Nabokov's Nikolka Persik translation, and his first three novels, placed fair-sized display ads. There were not many other authors who received such treatment.

It is impossible, though, to determine the exact date a book was published. But, by concentrating on the publisher and bookstore ads, it is possible to determine the week of publication.

The following is some evidence extracted from Rul'. It is neither complete nor definitive information on the publication and

[17]

criticism of a few of Nabokov's earliest works.

Gornii put', Berlin: Grani.

In Rul', 19 November 1922, p. 16, Grani placed a display ad for books on sale. Included is Gornii put' at 3 marks. In an earlier issue, 19 February 1922, Grani had listed a Sirin work 'Pechataiutsia' ['Being printed'], that could only have been Gornii put'. Though the title-page gives a publication year of 1923, it was certainly published and on sale in November 1922.

In Rul', 28 January 1923, p. 13, is a review by "В. K." of Grozd' and Gornii put', the former with a 1923 date, the latter with no date given.

Nikolka Persik, Berlin: Slovo.

In Rul', 26 November 1922, p. 13, under "New Books" appears the first mention of publication of this translation. A Slovo display ad, with prices, also appears in the same issue, on p. 15.

Grozd', Berlin: [Gamaiun].

The first Gamaiun ad in which Grozd' is listed appeared in Rul', 28 January 1923, p. 12 at 1.50 marks. However, except for this 'one date, no copies of Rul' for the first three months of 1923 are available and there may have been earlier ads for Grozd'. In that same issue, is a review by "В. K." of Grozd' and Gornii put'.

[18]

Ania v strane chudes', Berlin: Gamaiim.

Rul', 13 May 1923, p. 14, carried the first ad listing Ania у strane chudes'.

Mashken'ka, Berlin: Slovo.

Rul', 21 March 1926, carries the first ad for Mashen'ka, price $.80 American. It appears in the "Novyia knigi" ["New Books"] listing on 24 March 1926. The first specifically dated review was in Rul', 31 March 1926, by Iu. Aikhenval'd in the "Literaturnye zametki” ["Literary Notes"] column.

Korol' dama valet, Berlin: Slovo.

Rul', 23 September 1928, p. 9, carries the first display ad, by Slovo, for the book at $1.25 American. Also mentioned is Mashen'ka, at $.40 which later changed, in some ads, to 5.25 marks. In the same issue is an ad by the bookstore Moskva listing, among other authors' works, this first Nabokov novel. On 10 October 1928, it was in the new books listing, "Novyia knigi".

Zashchita Luzhina, Berlin: Slovo.

The first complete appearance of Zashchita Luzhina was its serialization in Sovremennyia Zapiski, Paris, No. XL (November 1929), pp. [163]-210, Chaps.1-4; No. XLI (January 1930), pp. [99]-164, Chaps. 5-9; No. XLI I (April 1930), pp. [127]-210, Chaps.10-14.

The first ad for the book was placed by Slovo in Rul', 21 September 1930, p. 4,

[19]

displaying this third novel, at $1.25 American dollars, along with their earlier releases of Mashen'ka, Korol' dama valet, and Vozvrashchenie Chorba. The same issue also had an ad by Moskva i Logos mentioning the book.

The first review of the book (the earlier appearance of the work in the journal had been commented on) was by A. Savel'ev in Rul', 1 October 1930, p. 5, on the literary page, "Kritika i Bibliografiia" ["Criticism and Bibliography"].

Vozvrashchenie Chorba, Berlin: Slovo.

A display ad by Slovo in Rul', 15 December 1929, p. 4, announced Vozvrashchenie Chorba for sale at $1.25 American. On the same page, the Moskva bookstore announced the coming availability of the book. A week later, a Moskva ad said the book was on sale. It was in the new book listing, "Novyia knigi", on 8 January 1930.

The Russian literary journal

In the English-writing and -reading world, bibliographers tend to relegate periodical appearances to back-room sections of their studies. This is a reflection of how literature is handled in our society. A literary composition has no passport, no identification papers, until it has appeared between covers and is put on sale as a book in a bookstore. Of course, we all read stories and poems and even novels in magazines and journals all the time. But do critics review them? Does the public respond to them as born and bawling

[20]

works? Do bibliographers state that in such-and-such an issue of Esquire appeared the first publications—the true first appearance — of Transparent Things?

The Russian literary world is different. Since the early 19th century (and also since the Revolution, both inside the Soviet Union and outside, in the emigration) many authors , especially the established ones, have had their major works, such as novels, published in the thick literary journals before they were published in separate book form. Such journal publication has been and still is considered--bibliographically speaking — the true first appearance of the work.

Sovremennyia Zapiski, published in Paris from 1920 to 1940, was such a "thick literary journal." It published, among other things, the last seven of Nabokov's nine Russian novels. Roughly speaking, these novels first appeared as a whole, though serialized, in Sovremennyia Zapiski; they were first read by the émigré population there; and, they were ingested from the journal, chewed on and, depending on tastes, digested or spat out at that point. And the critics reviewed the journals.

Many of the novels didn't appear in book form for years after their appearances in Sovremennyia Zapiski. Yet, readers were as fully aware of the novels as complete, finished and publicly published works as if they had come out as books. The appearances of the seven novels, therefore, in Sovremennyia Zapiski, and not their appearance in book form, should determine their chronology in a bibliography.

[21]

This leaves us with a new, though not yet complete chronology. The additional information has been garnered from Nabokov's introductions to his English language translations and other sources. Since Rul' stopped publishing in October 1931, the investigation will now shift to other daily journals, such as Poslednie Novosti. Therefore, all dates from the last quarter of 1931 and later are quite subject to change. Nabokov's later Russian works are here ignored.

A Brief Chronology of Major Russian Works

In Russia

1914 first poem composed

1916 Stikhi first book published

1918 Dva puti book published

In Western Europe

1922, Nov. Gornii put' book published

1922, Nov. Nikolka Persik book published

1923, Apr. Grozd' book published

1923, May Ania v strane chudes' book published

1925, sum: Mashen'ka writing began

1926, early Mashen'ka writing finished

1926, Mar. Mashen'ka excerpt appeared

[22]

1926, Mar. Mashen'ka book published

1927, sum. Korol' dama valet conceived

1927-8, win. Korol' dama valet writing began

1928, sum. Korol' dama valet writing finished

1928, Sep. Korol' dama valet excerpt appeared

1928, Sep. Korol' dama valet book published

1929, Spr. Zashchita Luzhina writing began

1929, Sep.,

thru 1930, Apr. Zashchita Luzhina excerpts appeared

1929, Nov.,

thru 1930, Aug. Zashchita Luzhina novel serialized

1929, Dec. Vozvrashchenie Chorba book published

1930, May Sogliadatai writing finished

1930, May Podvig writing began

1930, Sep Zashchita Luzhina book published

1930, Oct. Sogliadatai excerpt appeared

1930, Nov. Sogliadatai novel in periodical

1930, end Podvig writing finished

1931, Jan.,

thru 1932, Jan. Podvig excerpts appeared

[23]

1931, Feb.,

thru 1932, Feb?. Podvig novel serialized

1931, late,

thru 1932 Kamera obskura excerpts appeared

1932, 2nd half,

thru 1933, 1st half Kamera obskura novel serialized

1932 Kamera obskura book published

1932 Podvig book published

1932 Otchaianie written

1932, Dec.,

thru 1933, Nov. Otchaianie excerpts appeared

1934 Otchaianie novel serialized

1934 Priglashenie na kazn' written

1935-1937 Dar written

1935, late, thru

1936, early Priglashenie na kazn' novel serialized

1936 Otchaianie book published

1937, Mar., thru

1938, Feb. Dar excerpts appeared

1937-1938 Dar novel serialized

1938 Sogliadatai book published (with other stories)

[24]

1938 Priglashenie na kazn' book published

In Western Europe and the United States

1940/1942 Solus Rex excerpts appeared

In the United States 1

1952 Dar book published

ITEM 4

An update to item 1 in VNRN, No. 8, Spring 1982—

I have received additional information and a correction for a census of four rare Nabokov publications.

1) Stikhi, 1916, Petrograd, privately printed, numbered in black (stamped?), 1-500, on verso of title-page.

— one copy unnumbered, at the M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin State Public Library, Leningrad.

— copy no. 335, with the Nabokov family.

— copy no. 344, with the Nabokov family.

Vera Nabokov has corrected the rumor I reported earlier. She says, "The information that Nabokov advertised seeking this

[25]

book, and then destroyed the copies he bought is entirely fictitious. Actually, I placed once an ad seeking copies of the old editions and was able to acquire two novels. ..."

2) Al'manakh: Dva Puti, 1918, Petrograd, privately printed.

— two copies, with the Nabokov family.

— one copy, at the M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin State Public Library, Leningrad, now reported missing.

3) Camera Obscura, 1936, London, John Long, Ltd., translated by Winifred Roy

— one copy, with dust jacket, with the Nabokov family.

— one copy, at the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh

— one copy, in private hands.

Vera Nabokov says she knows nothing of the "cheap edition."

4) Despair, 1937, London, John Long, Ltd. , translated by the author.

— one copy, with the Nabokov family.

— one copy, at the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

I would appreciate any further citations or information.

[26]

ABSTRACT

"The Use of Female Characters in the Fiction of V. Nabokov"

by Paul Bennett Morgan National Library of Wales

(Abstract of Thesis for the award of M.A., University of Wales, 1980)

This study examines the special use of female characters in the novels and short stories of Vladimir Nabokov. It is not a hunt for 'proto-Lolitas' nor is it concerned with Nabokov's own attitudes to females in general (if, indeed, he had any such attitudes) .

A pattern may be discerned in the use of females which illuminates the works concerned, clarifies our understanding of Nabokov's literary technique and contributes to an understanding of two major themes which run through all his works: the ironic, even satiric perception of an imperfect world, and the passionate yearning for a blissful perfection which transcends it.

After a discussion of Nabokov's characterisation , in which the importance of his narrators is noted, along with Nabokov's acknowledgement of his characters' ultimate opacity, it is seen that his two main modes of presenting female characters reflect his two major themes: they function as embodiments of human fallibility and weakness, and as incarnations of ineffable beauty and perfection for the protagonists.

[27]

These contradictory functions are then explored, especially as they comment on the consciousness of the narrator (or protagonist) who perceives the female. Finally, the furthest sophistication of this technique is examined. When a single female is made to serve both purposes, ironic consequences are generated both for the female and the idealizing consciousness. In Lolita, however , both views of the female occur not only within one book but also within one consciousness: the narrator invests a female with his longings for an ideal beauty, yet also perceives she is utterly ordinary, even vulgar. At first, this situation leads him to his heartless use of her; finally, though, it facilitates a synthesis of the two views into a complete vision of Lolita, an enactment of the maturation of the narrator's perception and a reconciling of the major themes in Nabokov's fiction.

In this way, Nabokov uses his presentation of female characters to fight 'the utter degradation, ridicule and horror of having developed an infinity of sensation and thought within a finite existence'.

[28]

[29]

[30]

Nabokov in Literatura na Swiecie (Poland)

by Leszek Engelking

[Mr. Engleking is responding to the editor's request for precise information on publication in Poland.]

Vol. 12, No. 5-6 [May-June 1982] of the Polish monthly Literatura na Swiecie [Literature in the World] is mainly devoted to Vladimir Nabokov. This issue contains:

— Excerpts from Mary [Polish title: Maszeńka], fragments of chapter 2, chapter 3, chapter 4, fragment of chapter 13, chapters 14, 15 and 17, translated from the Russian by Eugenia Siemaszkiewicz, pp. 3-50;

— Excerpts from The Defense [Polish title: Obrona Luzyna], fragment of chapter 1, chapter 4, fragment of chapter 6 and fragment of chapter 14, translated from the Russian by E. Siemaszkiewicz, pp. 56-109;

— Excerpts from Invitation to a Beheading [Polish title: Zaproszenie na egzekucje], chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 9 and 13, translated from the Russian by Leszek Engelking, pp.120-178;

— Excerpts from Other Shores [Polish title: Tamte brzegi], "Introduction to the Russian Edition", chapter 1/1, 2/ and the whole of chapter 7, translated from the Russian by E. Siemaszkiewicz, pp. 180-211;

[31]

— L. Engelking's translations of seven Nabokov poems: pp. 52-55/: 1923 poem without title /"Berezhno nyos ya..."/, "V rayu" /"Moya dusha...", [Polish title:"W raju"], "Na zakate" [Polish title : "O zachodzie"], "Chto za noch' sluchhos' s pamyatyu" [Polish title: "Co sie stalo z pamiecia dzis noca"], "Neuralgia intercostalis", 1965 poem without title /"Sred' etikh Ustvennits. . ."/ and "Rain" [PoUsh title: "Deszcz"]; the last text is the only translation from English;

— "Kalendarium zycia i tworczosci Wladimira Nabokowa: ["A Chronology of Vladimir Nabokov's Life and Work"] by L. Engelking, pp. 212-225;

— An essay about Invitation to a Beheading entitled "Zaproszenie do odrozy" ["Invitation to a Journey"] also by L. Engelking, pp. 110-119, and — last but not least — a presentation of the VNRN:

— L. Engelking's "The Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter - czasopismo poswiecone tworczosci Nabokowa" /"The Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter — a Journal Devoted to Nabokov and His Work"/, pp. 226-227.

This is not the first appearance of Nabokov in Literatura na Swiecie. Large parts of Vol. 8, No. 8 (August 1978) were also devoted to him. That issue contains:

— Robert Stiller's translation of "The Vane Sisters" [Polish title: "Siostry Vane"], pp. 6-27.

[32]

— Jaroslaw Anders' translation from Ada, excerpts from Part One (chapters 1, 2 and fragment of chapter 3), pp. 28-55;

— Ariadna Demkowska-Bohdziewicz's translation from Transparent Things (published under the English title), chapters 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11, pp. 56-77;

— R. Stiller's translation from Nabokov's commentary to Eugene Onegin, comments on the first three stanzas of Pushkin's work, pp. 108-137;

— The English text and R. Stiller's translation of "An Evening of Russian Poetry" [Polish title: "Odczyt о poezji rosyjskiej"], pp. 138-163;

— Romana Cekalska's translation from Nikolay Gogol [Polish title: Mikolaj Gogol], chapter 5 "The Apotheosis of a Mask" [Polish title: "Pochwala maski"], pp. 164-175;

— R. Stiller's "Wywiad z Nabokovem" ("An Interview with Nabokov"): a fictive one, combinations of fragments of various Nabokov interviews and articles contained in Strong Opinions, pp. 78-107;

— J. Anders' translation of large excerpts from Clarence Brown's "Nabokov's Pushkin and Nabokov's Nabokov" [Polish title: "Puszkin Nabokova i Nabokova Nabokov"], pp. 176-191, and

— Lech Budrecki's paper "Nabokov i literatura" ("Nabokov and Literature"), pp. 192-215.

[34]

All translations in the issue are, of course, from English.

Literatura na Swiecie is considering publishing some of Nabokov's works and some essays about the writer next year.

[35]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

(Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov's works will be to the most recent hardcover U.S. editions.)

"That main secret tra-ta-ta tra-ta-ta tra-ta-" (Fame, 105).

In the Appel and Newman festschrift, Robert P. Hughes discusses, among other things, "Mali è trano t'amesti," sung by Marthe's brother at the family gathering ("Notes on the Translation of Invitation to a Beheading," Nabokov, p. 291); he notes that it may contain some "probably misleading but suspiciously Russian-looking fragments," cautiously concluding that "a … worker of anagrams may ferret out in full yet another magic phrase." One may add that, first, this pseudo-Italian snatch of an "aria" is sung twice in the course of that nightmare reunion (Invitation, p.103); and that, second, the brunet brother is said to be a singer. Indeed, the operatic theme in the book has some interesting farcical recurrences, from Rodion's singing in the "imitation-jaunty pose of operatic rakes in the tavern scene," to M'sieur Pierre's Singspiel attire, to the "new comic opera Socrates

[35]

Must Decrease" announced from the block to be performed after the execution (it is not unlikely that Marthe's brother was supposed to participate and thus was rehearsing his aria in Cincinnatus's cell).

Now, the phrase in question is indeed magical. Upon thorough reshuffling of its letters and diacritics one comes out with the following Russian sentence:

Smert' mila eto taina / Death is sweet; that's a secret.

One will note that the way of transliteration is rather typical of Nabokov at the time (the apostrophe in t'amesti standing for the soft sign, and the accent aigu denoting the Russian 3). A dash or semicolon in the middle of the phrase seems somewhat desirable. One will also mark that this overeager fellow was hushed by his brother immediately after his sonorous outburst as if he had really let out an important secret (perhaps, just another treacherous and torturing trap which, however, went unnoticed by Cincinnatus ).

The coded sentence has numerous thematic possibilities and a definite connection with the book's motto. One wonders whether it may not be a paraphrase of a Russian version of some real libretto, Faust or the like.

— Gene Barabtarlo, The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

[36]

Time in The Gift

The Gift opens around four in the afternoon of April first and closes on a mild evening three years and three months later, on a June twenty-ninth. In a conversation on that June 29, Nabokov's hero Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev makes a remark very characteristic of his creator: "The most enchanting things in nature and art are based on deception" (p. 376). And the novel begins, appropriately enough, with a typically Nabokovian deception: "One cloudy but luminous day, towards four in the afternoon, on April the first, 192—( … Russian authors ... in keeping with the honesty peculiar to our literature, omit the final digit) …"

In his brief introduction to the English translation, Nabokov mentions the time of his novel in a general fashion: "circa 1925." But although he somewhat obscures the exact year of the novel's inception, he gives clues later which tell the reader when the action of the book takes place. The most precise intimation of the date is provided in the fifth chapter; using the information about the book reviews of the biography of Nikolay Chernyshevsky and the Shchyogolevs’ departure for Denmark, one can say with certainty that the story closes on June 29, 1928. Thus the date the story opens can also be fixed: April 1, 1925.

In the first two chapters, Fyodor lives at Frau Klara Stoboy's for exactly two years, from April 1, 1925 to March 31, 1927. The posthumous biography in the first chap-

[37]

ter is composed two years after Mme Chernyshevsky has lost her only son (p. 48). Yasha Chernyshevsky had shot himself on April 18, 1923, a few months before "Lenin met a sloppy end" in January, 1924, and before "Duse, Puccini and Anatole France died," all in 1924 (pp. 58, 60, 62). On April 1, 1925 Fyodor recalls that over seven years have passed since the October Revolution (p. 29). That evening, he hears a conversation about "some unlamented Soviet politician who had fallen from power after Lenin's death" (p. 47). That political leader is probably Leon Trotsky, who had been removed from his post as war commissar in January, 1925.

Fyodor's mother comes to visit him in Berlin at Christmas that same year, and as a result of their discussions of Fyodor's father, especially the circumstances of his death, Fyodor spends the next year and three months working on the biography of his father. Fyodor then moves to Agamemnonstrasse and meets Zina Mertz on March 31, 1927 (p. 156). Early in the third chapter, he remembers that his Poems had been published "two years ago" (p. 167). And he further recalls (still in early April, 1927) his initial reactions to the rhythm studies of Andrei Bely, "the author of Moscow" (p. 169); this novel by Bely had in fact been published in full only in 1926.

On a Friday in early April, 1927, he has his first significant encounter with Zina, "about ten days after they became acquainted" (p. 191). The next Sunday, they have a long conversation, during which Fyodor

[38]

discovers that Zina is his most ardent admirer (pp. 191-94). A short time after that he meets with the Chernyshevskys and announces that he plans to write a biography of Nikolay Chernyshevsky, following the advice given him by Alexander Chernyshevsky "about three years ago" (p. 208). This calculation stretches the interval between suggestion and decision rather significantly, from a little over two to "about" three years. The reports of the progress on the biography that follow indicate that Fyodor composes it during the winter of 1927-28 and finishes it in time for publication around Easter, 1928.

Nabokov, however, inserts a comment near the end of the third chapter that shifts the narrative back to the original time frame: Fyodor meets an un talented but helpful fellow writer named Busch, whom he recalls seeing "two and a half years ago" (p. 221), at a literary gathering shortly before his mother's Christmas visit. Further references in the fifth chapter make it obvious that the final events reported in the novel take place one year and three months — exactly "four hundred and fifty-five days" (p. 374)-— after Fyodor had met Zina. Fyodor's last conversation with Zina's stepfather, Shchyogolev, also emphasizes that he and they "had one year and a half of cohabitation" (p. 360). To make it even clearer, Zina and Fyodor are shown retracing the twists of fate that began to bring them together (though they did not actually meet at that time) "three and a half odd years" earlier (p. 375), i.e., at the beginning of the book.

[39]

The penultimate day of the story is named: "on the twenty-eighth of June, around three p.m." (p. 348), Fyodor finishes a swim in a private creek in the Grunewald. On that day, before the Shchyogolevs leave for Copenhagen by train, Fyodor contemplates the "beginning (tomorrow night!) of his full life with Zina" (p. 357). The actual day of the departure, June 29, is "some kind of national holiday" in Berlin (p. 370), with parades and flags everywhere.

Fyodor's biography has come out about two months before this date; as one of the reviews of the book makes clear, the biography has appeared almost exactly one hundred years after N. Chernyshevsky's birth on July 12, 1828, O.S. (pp. 320-21). This clue is in fact the most direct one about the precise year, but there are other hints in the same chapter that also point to 1928. The mention of a leap year, which 1928 was, contains one of these hints (p. 347); and the statement that the writer Vladimirov, who Nabokov admits in the Foreword represents himself, was twenty-nine years old that year, as was Nabokov in April, 1928, is another that provides added support to the view that The Gift ends in 1928.

Unlike other, more "enchanting" deceptions , this coquettishness about time is related to the chess problems that appealed so much to Fyodor (and his author). The almost transparent deceit that partly camouflages the precise years of the novel's action is designed to be discovered and resolved logically, somewhat like a riddle. The out-

[40]

come, therefore, is that the novel begins not in 192—, but in 1925, and ends during the centenary of Cherny shevsky's birth in 1928.

—Ronald E. Peterson, Occidental College, Los Angeles

The "Yablochko" Chastushka in Bend Sinister

Bend Sinister (1947), Nabokov's first American novel, contains a great many allusions for which his new readers were ill equipped. After the success of Lolita, Time-Life Books reissued the earlier novel in paperback with a new introduction by the author (1964), also included in the later McGraw-Hill edition (1973). This Introduction (the only one to a Nabokov novel first written in English — Lolita has an afterword) is the most informative among Nabokov's prefaces in its explication of various arcane references. There are, nonetheless, many allusions still awaiting their annotators.

Near the end of the novel Krug, having capitulated to the demands of the Ekwilist regime, is taken to be reunited with his son David; by administrative error, however, the boy has been inadvertently murdered. Krug is finally allowed to see the garishly laid-out body. Maddened by grief, Krug starts to run out of the room but is restrained by a "friendly soldier" who says "Yablochko, kuda-zh ty tak kotishsa [little apple, whither are you rolling]?" (p. 225). The immediate meaning is obvious: "Where do you think you are going?" But why this

[41]

very folksy Russian expression? The first sublayer of meaning is not difficult: throughout the novel an "apple motif" is attached to the hero Adam Krug (see especially the Adam's apple allusion on p. 47). Nabokov's allusions are often multileveled, however. The subtext of the soldier's phrase is the beginning of a four-line chastushka that was enormously popular in the early years of the Revolution. The chastushka form is a sort of ditty, often humorous and epigrammatic (and at times vulgar), usually socio-political in content.

This particular chastushka had a multitude of variants among both Reds and Whites. An early example (Odessa, 1917) is based upon an incident that occurred on the Black Sea naval vessel Almaz when a group of White army officers were hanged by the seamen: "Oy, yablochko, / Kuda kotishsya?

/ Na "Almaz" popadёsh, / Ne vorotishsya! " (Oy, little apple / Where are you rolling? / If you get to the Almaz / You won't come back!). A later Kiev variant substitutes Chrezvychayku (the office of the Cheka, the dread political police) for Almaz. A White variant was "Oy, yablochko, / Katish parami:/ Budem ryb kormit' / Kommissarami!" (Oy, little apple / Roll in pairs: / We shall feed the fish / With Commissars!). Hundreds of the "little apple" quatrains have been collected by Russian folklorists, and Nabokov very likely heard examples himself during his sojourn in the south of Russia where they were especially popular during the Civil War. From there the little apple rolled into Bend Sinister.

[42]

Another reference to this chastushka occurs in a similar context in Look at the Harlequins! (p. 10). As Vadim Vadimovich flees across the Russo-Polish frontier in 1918 he is challenged by a Red Army border guard: "And whither … may you be rolling (kotishsya), little apple (yablochko)?" VV responds by shooting him dead.

Although no longer current, the "yablochko" chastushki have been used by Soviet artists as "local color." Some examples: poet Sergej Esenin's "Pesnya о velikom poxode" (Song of a Great Campaign, 1924); Mikhail Svetlov's popular poem-become-song "Grenada" (1926), and A. Prokof'ev's "Matrosy peli ’Yablochko"' (The Sailors Sang "Little Apple"). The only other English-language reference that I have encountered is by Nabokov's fellow Anglo-Russian writer Ayn Rand (b. Petersburg, 1905), who makes the chastushka one of the motifs of her awful revolutionary epic We the Living (1936) (Signet Y4440, pp. 18-19, 110, 336-37).

—D. Barton Johnson, University of California at Santa Barbara