by Zoran Kuzmanovich

It is with deepening sadness that I report the passing of Don Johnson who died August 25, 2020 at Villa Alamar, a Santa Barbara memory-care facility. Don was 87. He was born on June 15, 1933 near Ladoga, Indiana. He attended Indiana University for his BA degree in Russian and UC Berkeley for his MA in economics. He received his PhD from the UCLA Slavic Department with a thesis titled “Transform Analysis of Russian Prepositional Constructions.” The thesis was a work that investigated the parameters for the then-new field of computer-aided machine translation. After receiving his doctoral degree, Don taught briefly at Ohio State University before returning to California to teach at UC-Santa Barbara. Having started his series of publications on Nabokov as early as 1971, Don was the first Nabokov scholar to teach a course devoted only to Nabokov and became the central figure in shaping the field of Nabokov studies not only through his witty incisive wide-ranging essays (collected in Worlds in Regression), but also by serving twice as the President of the International Vladimir Nabokov Society. From the very beginning of the field of Nabokov studies, Don encouraged, stimulated, challenged and nourished scholarship on Nabokov by creating venues, forums, and formats to promote the work of others. The first such effort was the peer-reviewed print journal Nabokov Studies. It was followed by NABOKV-L, the Electronic Nabokov Discussion Forum which Don moderated for over a decade. Two annual prizes were created in Don’s name to recognize his work on Nabokov. One honors the best essay published in Nabokov Studies. The other is given for the best undergraduate work on Nabokov done at UC-Santa Barbara.

Don is survived by his wife and occasional collaborator Sheila Goldburgh Johnson and his stepchildren Aaron Moody and Jessica Dora. In his characteristic modesty, Don has asked for no memorial service beyond the private family one. There is no information yet on memorial donations.

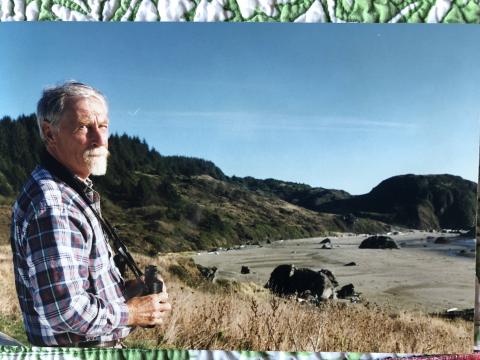

That much is public record. But while it takes notice of Don’s innovative scholarly methods, the public record fails to emphasize Don’s generosity, playfulness, and skilled literary detective work for which his experience with birding and his brief employment at the National Security Agency had been appropriate preparation. It also fails to account for the manner in which Don peregrinated among, tunneled through, or levitated above Nabokov’s interwoven Russian and English works. For four decades Don kept writing essays that were genuinely at home in the great and not-so-great Russian, English, German and French works of literature that the young Nabokov first imbibed and then wove into the texture of his creative and scholarly output. And then, of course, there are Don’s other areas of Nabokovian expertise: alphabetic chromesthesia, alphabetic iconicism, alphabetic paronomasia, microstylistics, butterflies, paintings, genealogies, chess, synaesthesia and polychromatism, Ayn Rand and Mayne Reid, Greta Garbo, tobacco types, and God knows what else.

The public notice also does not begin to suggest Don’s sensitivity to nuance and his unerring nose for the vividness of Nabokovian details, especially those that integrate plot, motif, theme both within and among Nabokov’s works. In the late 1970s and early 1980s when Nabokov was being studied as a clever stylist, parodist, and metafictionist puzzlemaker escaping into aesthetics from the pressures of history, emotions, and morality, critics new to the field sought for a Nabokov who was serious, tender, relevant, and even prophetic. Véra Nabokov supplied just such a Nabokov by declaring that the “beyond” was Nabokov’s “main theme,” and a number of critics followed suit in repositioning Nabokov as escaping not into aesthetics but into a mistily repetitive Neoplatonic gnosis. Like Brian Boyd, Sergei Davydov, and Priscilla Meyer, Don quietly treated Véra Nabokov’s declaration as an overstatement to which she was entitled and continued to examine the ways in which Nabokov’s brilliant narrative techniques sent the reader from Nabokov’s patterned use of a single letter to implied two-world aesthetic cosmologies, with the key difference being that for Don it was never the same two worlds from one Nabokov book to another.

Don’s generosity to incoming Nabokov scholars is legendary. Without such generosity, my scholarly life would be very much poorer on a number of levels. His hospitality is no less the stuff of great stories: his generous pour of Scotch, his quiet warning about the rattlesnakes under the Ceanothus, his recounting of the actions of a man who mistook Don’s house for a laundromat. To those who were not fortunate enough to visit his house on Tunnel Road, Don’s generosity is evident in his reviews of other scholars’ work. In fact, Don’s skill at sympathetic exposition in his reviews often makes you wish he had written the book he was reviewing. Don’s own prose is never marred by false profundity or namedropping, and he remained wonderfully uninfected by the theoretical equivalent of COVID-19 that ravaged US campuses during the last three decades of the 20th century. Don’s brevity, clarity, candor, and good will were evident in everything he did. When I took over the editing duties for Nabokov Studies, Don made certain I fully understood the challenge of evaluating papers by friends and former mentors. I owe to Don whatever moral calcium there is in my editorial backbone from learning to recognize and respect the difference between the well-wrought and the overwrought. In a few cases such respect has meant the loss of good friends who had allowed the flavor of their own prose to absorb a lethal dose of Nabokov’s and did not appreciate having that unconscious contamination pointed out to them.

My intention to write a doctoral thesis on Katherine Mansfield got re-evaluated after a reading of Don’s articles on the fate of Nabokov’s works in Soviet Russia, a belatedness and indebtedness I must mention and celebrate here. To quote Sam Schuman, another generous pioneer of Nabokov studies, “Whenever and wherever we talk about Nabokov, in speech, in print, and electronically, Don has been there first.” And while he was there, ahead of many of us, Don seems to have dropped the kind of scholarly crumbs that when consumed and thoroughly digested lead us to an appreciation of the movingly mysterious in Nabokov’s work. The benefit of those crumbs is such that they let us find a state from which we can value Nabokov’s work as a marvelous thing in the world rather than as merely a question Nabokov put to the world or to us.

Don’s integrity, curiosity, innovation, and generosity of spirit are legacies in themselves and tools by which we ought to direct and measure the light we think we generate as critics of Nabokov’s work. Quite simply, Don’s work and the dissemination pattern of that work teach us to seek in Nabokov’s work more of Nabokov and less of ourselves. While we may never fully master that lesson, we thank D. Barton Johnson for delivering the lesson in so convincing and so memorable a fashion.

Comments