The poet in VN’s novel Pale Fire (1962), John Shade lives in the frame house between Goldsworth and Wordsmith:

I cannot understand why from the lake

I could make out our front porch when I'd take

Lake Road to school, whilst now, although no tree

Has intervened, I look but fail to see

Even the roof. Maybe some quirk in space

Has caused a fold or furrow to displace

The fragile vista, the frame house between

Goldsworth and Wordsmith on its square of green. (Lines 41-48)

In his note to Lines 47-48 (the frame house between Goldsworth and Wordsmith) Kinbote (Shade’s mad commentator who imagines that he is Charles the Beloved, the last self-exiled king of Zembla) writes:

The first name refers to the house in Dulwich Road that I rented from Hugh Warren Goldsworth, authority on Roman Law and distinguished judge. I never had the pleasure of meeting my landlord but I came to know his handwriting almost as well as I do Shade's. The second name denotes, of course, Wordsmith University. In seeming to suggest a midway situation between the two places, our poet is less concerned with spatial exactitude than with a witty exchange of syllables invoking the two masters of the heroic couplet, between whom he embowers his own muse. Actually, the "frame house on its square of green" was five miles west of the Wordsmith campus but only fifty yards or so distant from my east windows.

“The two masters of the heroic couplet” mentioned by Kinbote are Oliver Goldsmith (an Irish poet, playwright, essayist and novelist, 1728-74) and William Wordsworth (an English poet, 1770-1850). Thackeray called Goldsmith "the best beloved of English writers." At the end of his essay Robert Louis Stevenson (1895) Walter Raleigh (a namesake of an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer of the Elizabethan era) pairs Stevenson with Goldsmith and Montaigne and quotes Thackeray's words about Goldsmith:

Lastly, to bring to an end this imperfect review of the works of a writer who has left none greater behind him, Stevenson excels at what is perhaps the most delicate of literary tasks and the utmost test, where it is successfully encountered, of nobility, - the practice, namely, of self-revelation and self-delineation. To talk much about oneself with detail, composure, and ease, with no shadow of hypocrisy and no whiff or taint of indecent familiarity, no puling and no posing, - the shores of the sea of literature are strewn with the wrecks and forlorn properties of those who have adventured on this dangerous attempt. But a criticism of Stevenson is happy in this, that from the writer it can pass with perfect trust and perfect fluency to the man. He shares with Goldsmith and Montaigne, his own favourite, the happy privilege of making lovers among his readers. 'To be the most beloved of English writers - what a title that is for a man!' says Thackeray of Goldsmith. In such matters, a dispute for pre-eminence in the captivation of hearts would be unseemly; it is enough to say that Stevenson too has his lovers among those who have accompanied him on his INLAND VOYAGE, or through the fastnesses of the Cevennes in the wake of Modestine. He is loved by those that never saw his face; and one who has sealed that dizzy height of ambition may well be content, without the impertinent assurance that, when the Japanese have taken London and revised the contents of the British Museum, the yellow scribes whom they shall set to produce a new edition of the BIOGRAPHIE UNIVERSELLE will include in their entries the following item: - 'STEVENSON, R. L. A PROLIFIC WRITER OF STORIES AMONG THE ABORIGINES. FLOURISHED BEFORE THE COMING OF THE JAPANESE. HIS WORKS ARE LOST.'

"Flourished before the coming of the Japanese" brings to mind J. D. Salinger's story Just Before the War with the Eskimos (1948) and Mr. Yoshoto, a character in Salinger's story De Daumier-Smith's Blue Period (1952). The epigraph to Salinger’s “Nine Stories” is a Zen koan: “We know the sound of two hands clapping. But what is the sound of one hand clapping?” Describing his rented house, Kinbote mentions Judge Goldsworth's wife whose intellectual interests are fully developed, going as they do from Amber to Zen:

In the Foreword to this work I have had occasion to say something about the amenities of my habitation. The charming, charmingly vague lady (see note to line 691), who secured it for me, sight unseen, meant well, no doubt, especially since it was widely admired in the neighborhood for its "old-world spaciousness and graciousness." Actually, it was an old, dismal, white-and-black, half-timbered house, of the type termed wodnaggen in my country, with carved gables, drafty bow windows and a so-called "semi-noble" porch, surmounted by a hideous veranda. Judge Goldsworth had a wife, and four daughters. Family photographs met me in the hallway and pursued me from room to room, and although I am sure that Alphina (9), Betty (10), Candida (12), and Dee (14) will soon change from horribly cute little schoolgirls to smart young ladies and superior mothers, I must confess that their pert pictures irritated me to such an extent that finally I gathered them one by one and dumped them all in a closet under the gallows row of their cellophane-shrouded winter clothes. In the study I found a large picture of their parents, with sexes reversed, Mrs. G. resembling Malenkov, and Mr. G. a Medusa-locked hag, and this I replaced by the reproduction of a beloved early Picasso: earth boy leading raincloud horse. I did not bother, though, to do much about the family books which were also all over the house - four sets of different Children's Encyclopedias, and a stolid grown-up one that ascended all the way from shelf to shelf along a flight of stairs to burst an appendix in the attic. Judging by the novels in Mrs. Goldsworth's boudoir, her intellectual interests were fully developed, going as they did from Amber to Zen. The head of this alphabetic family had a library too, but this consisted mainly of legal works and a lot of conspicuously lettered ledgers. All the layman could glean for instruction and entertainment was a morocco-bound album in which the judge had lovingly pasted the life histories and pictures of people he had sent to prison or condemned to death: unforgettable faces of imbecile hoodlums, last smokes and last grins, a strangler's quite ordinary-looking hands, a self-made widow, the close-set merciless eyes of a homicidal maniac (somewhat resembling, I admit, the late Jacques d'Argus), a bright little parricide aged seven ("Now, sonny, we want you to tell us -"), and a sad pudgy old pederast who had blown up his blackmailer. What rather surprised me was that he, my learned landlord, and not his "missus," directed the household. Not only had he left me a detailed inventory of all such articles as cluster around a new tenant like a mob of menacing natives, but he had taken stupendous pains to write out on slips of paper recommendations, explanations, injunctions and supplementary lists. Whatever I touched on the first day of my stay yielded a specimen of Goldsworthiana. I unlocked the medicine chest in the second bathroom, and out fluttered a message advising me that the slit for discarded safety blades was too full to use. I opened the icebox, and it warned me with a bark that "no national specialties with odors hard to get rid of" should be placed therein. I pulled out the middle drawer of the desk in the study - and discovered a catalogue raisonné of its meager contents which included an assortment of ashtrays, a damask paperknife (described as "one ancient dagger brought by Mrs. Goldsworth's father from the Orient"), and an old but unused pocket diary optimistically maturing there until its calendric correspondencies came around again. Among various detailed notices affixed to a special board in the pantry, such as plumbing instructions, dissertations on electricity, discourses on cactuses and so forth, I found the diet of the black cat that came with the house:

Mon, Wed, Fri: Liver

Tue, Thu, Sat: Fish

Sun: Ground meat

(All it got from me was milk and sardines; it was a likable little creature but after a while its movements began to grate on my nerves and I farmed it out to Mrs. Finley, the cleaning woman.) But perhaps the funniest note concerned the manipulations of the window curtains which had to be drawn in different ways at different hours to prevent the sun from getting at the upholstery. A description of the position of the sun, daily and seasonal, was given for the several windows, and if I had heeded all this I would have been kept as busy as a participant in a regatta. A footnote, however, generously suggested that instead of manning the curtains, I might prefer to shift and reshift out of sun range the more precious pieces of furniture (two embroidered armchairs and a heavy "royal console") but should do it carefully lest I scratch the wall moldings. I cannot, alas, reproduce the meticulous schedule of these transposals but seem to recall that I was supposed to castle the long way before going to bed and the short way first thing in the morning. My dear Shade roared with laughter when I led him on a tour of inspection and had him find some of those bunny eggs for himself. Thank God, his robust hilarity dissipated the atmosphere of damnum infectum in which I was supposed to dwell. On his part, he regaled me with a number of anecdotes concerning the judge's dry wit and courtroom mannerisms; most of these anecdotes were doubtless folklore exaggerations, a few were evident inventions, and all were harmless. He did not bring up, my sweet old friend never did, ridiculous stories about the terrifying shadows that Judge Goldsworth's gown threw across the underworld, or about this or that beast lying in prison and positively dying of raghdirst (thirst for revenge) - crass banalities circulated by the scurrilous and the heartless - by all those for whom romance, remoteness, sealskin-lined scarlet skies, the darkening dunes of a fabulous kingdom, simply do not exist. But enough of this. Let us turn to our poet's windows. I have no desire to twist and batter an unambiguous apparatus criticus into the monstrous semblance of a novel. (note to Lines 47-48)

The three main characters in Pale Fire are the poet Shade, his commentator Kinbote and his murderer Gradus. Describing Gradus’ day in New York, Kinbote mentions a Zemblan moppet and her Japanese friend:

He [Gradus] began with the day's copy of The New York Times. His lips moving like wrestling worms, he read about all kinds of things. Hrushchov (whom they spelled "Khrushchev") had abruptly put off a visit to Scandinavia and was to visit Zembla instead (here I tune in: "Vï nazïvaete sebya zemblerami, you call yourselves Zemblans, a ya vas nazïvayu zemlyakami, and I call you fellow countrymen!" Laughter and applause.) The United States was about to launch its first atom-driven merchant ship (just to annoy the Ruskers, of course. J. G.). Last night in Newark, an apartment house at 555 South Street was hit by a thunderbolt that smashed a TV set and injured two people watching an actress lost in a violent studio storm (those tormented spirits are terrible! C. X. K. teste J. S.). The Rachel Jewelry Company in Brooklyn advertised in agate type for a jewelry polisher who "must have experience on costume jewelry (oh, Degré had!). The Helman brothers said they had assisted in the negotiations for the placement of a sizable note: "$11, 000, 000, Decker Glass Manufacturing Company, Inc., note due July 1, 1979," and Gradus, grown young again, reread this this twice, with the background gray thought, perhaps, that he would be sixty-four four days after that (no comment). On another bench he found a Monday issue of the same newspaper. During a visit to a museum in Whitehorse (Gradus kicked at a pigeon that came too near), the Queen of England walked to a corner of the White Animals Room, removed her right glove and, with her back turned to several evidently observant people, rubbed her forehead and one of her eyes. A pro-Red revolt had erupted in Iraq. Asked about the Soviet exhibition at the New York Coliseum, Carl Sandburg, a poet, replied, and I quote: "They make their appeal on the highest of intellectual levels." A hack reviewer of new books for tourists, reviewing his own tour through Norway, said that the fjords were too famous to need (his) description, and that all Scandinavians loved flowers. And at a picnic for international children a Zemblan moppet cried to her Japanese friend: Ufgut, ufgut, velkam ut Semblerland! (Adieu, adieu, till we meet in Zembla!) I confess it has been a wonderful game - this looking up in the WUL of various ephemerides over the shadow of a padded shoulder. (note to Line 949)

The WUL is the abbreviation of Wordsmith University Library. Gradus' birthday, July 5, is also Shade's and Kinbote's birthday (while Shade was born in 1898, Kinbote and Gradus were born in 1915). Describing Shade's birthday party, Kinbote mentions "the Bustle and Vanity of the World." Vanity Fair (1847-48) is a novel by Thackeray. In his essay An Apology for Idlers (1877) R. L. Stevenson mentions "all the bustle and glamor of reality." Kinbote's note to Line 493 (She took her poor young life) is not an apology of suicide – it is the simple and sober description of a spiritual situation.

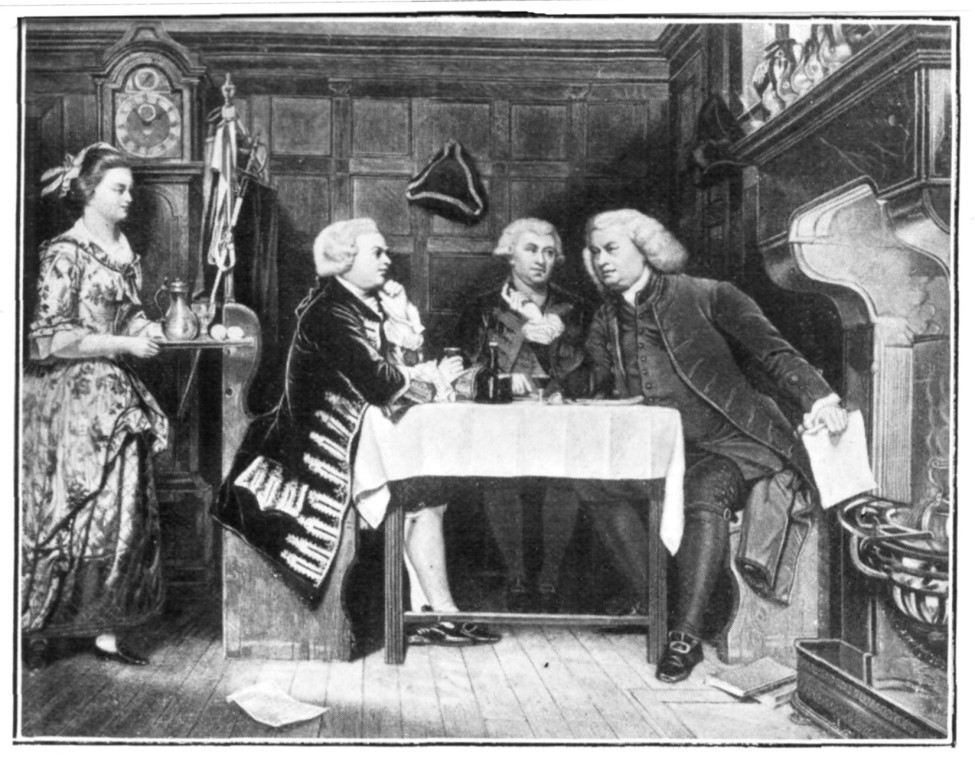

DR. JOHNSON, BOSWELL AND GOLDSMITH, AT THE MITRE TAVERN. (From the painting by Eyre Crowe.) The epigraph to Pale Fire is from James Boswell’s biography of Samuel Johnson:

DR. JOHNSON, BOSWELL AND GOLDSMITH, AT THE MITRE TAVERN. (From the painting by Eyre Crowe.) The epigraph to Pale Fire is from James Boswell’s biography of Samuel Johnson:

This reminds me of the ludicrous account he gave Mr. Langston, of the despicable state of a young gentleman of good family. 'Sir, when I heard of him last, he was running about town shooting cats.' And then in a sort of kindly reverie, he bethought himself of his own favorite cat, and said, 'But Hodge shan't be shot: no, no, Hodge shall not be shot.'

- James Boswell, the Life of Samuel Johnson

The epigraph to R. L. Stevenson's essay An Apology for Idlers is from the same book:

BOSWELL: We grow weary when idle.

JOHNSON: That is, sir, because others being busy, we want company; but if we were idle, there would be no growing weary; we should all entertain one another."

R. L. Stevenson is the author of A Chapter on Dreams (1888). At the end of his lecture on dreams Van Veen (the narrator and main character in VN's novel Ada, 1969) mentions Walter Raleigh’s decapitated trunk still topped by the image of his wetnurse (Sir Walter Raleigh was sentenced to death in 1603 and beheaded on 29 October 1618):

I have some notes here on the general character of dreams. One puzzling feature is the multitude of perfect strangers with clear features, but never seen again, accompanying, meeting, welcoming me, pestering me with long tedious tales about other strangers — all this in localities familiar to me and in the midst of people, deceased or living, whom I knew well; or the curious tricks of an agent of Chronos — a very exact clock-time awareness, with all the pangs (possibly full-bladder pangs in disguise) of not getting somewhere in time, and with that clock hand before me, numerically meaningful, mechanically plausible, but combined — and that is the curious part — with an extremely hazy, hardly existing passing-of-time feeling (this theme I will also reserve for a later chapter). All dreams are affected by the experiences and impressions of the present as well as by memories of childhood; all reflect, in images or sensations, a draft, a light, a rich meal or a grave internal disorder. Perhaps the most typical trait of practically all dreams, unimportant or portentous — and this despite the presence, in stretches or patches, of fairly logical (within special limits) cogitation and awareness (often absurd) of dream-past events — should be understood by my students as a dismal weakening of the intellectual faculties of the dreamer, who is not really shocked to run into a long-dead friend. At his best the dreamer wears semi-opaque blinkers; at his worst he’s an imbecile. The class (1891, 1892, 1893, 1894, et cetera) will carefully note (rustle of bluebooks) that, owing to their very nature, to that mental mediocrity and bumble, dreams cannot yield any semblance of morality or symbol or allegory or Greek myth, unless, naturally, the dreamer is a Greek or a mythicist. Metamorphoses in dreams are as common as metaphors in poetry. A writer who likens, say, the fact of imagination’s weakening less rapidly than memory, to the lead of a pencil getting used up more slowly than its erasing end, is comparing two real, concrete, existing things. Do you want me to repeat that? (cries of ‘yes! yes!’) Well, the pencil I’m holding is still conveniently long though it has served me a lot, but its rubber cap is practically erased by the very action it has been performing too many times. My imagination is still strong and serviceable but my memory is getting shorter and shorter. I compare that real experience to the condition of this real commonplace object. Neither is a symbol of the other. Similarly, when a teashop humorist says that a little conical titbit with a comical cherry on top resembles this or that (titters in the audience) he is turning a pink cake into a pink breast (tempestuous laughter) in a fraise-like frill or frilled phrase (silence). Both objects are real, they are not interchangeable, not tokens of something else, say, of Walter Raleigh’s decapitated trunk still topped by the image of his wetnurse (one lone chuckle). Now the mistake — the lewd, ludicrous and vulgar mistake of the Signy-Mondieu analysts consists in their regarding a real object, a pompon, say, or a pumpkin (actually seen in a dream by the patient) as a significant abstraction of the real object, as a bumpkin’s bonbon or one-half of the bust if you see what I mean (scattered giggles). There can be no emblem or parable in a village idiot’s hallucinations or in last night’s dream of any of us in this hall. In those random visions nothing — underscore ‘nothing’ (grating sound of horizontal strokes) — can be construed as allowing itself to be deciphered by a witch doctor who can then cure a madman or give comfort to a killer by laying the blame on a too fond, too fiendish or too indifferent parent — secret festerings that the foster quack feigns to heal by expensive confession fests (laughter and applause). (2.4)

At the end of his Commentary Kinbote quotes the words of his Zemblan nurse:

Many years ago--how many I would not care to say--I remember my Zemblan nurse telling me, a little man of six in the throes of adult insomnia: "Minnamin, Gut mag alkan, Pern dirstan" (my darling, God makes hungry, the Devil thirsty). Well, folks, I guess many in this fine hall are as hungry and thirsty as me, and I'd better stop, folks, right here.

Yes, better stop. My notes and self are petering out. Gentlemen, I have suffered very much, and more than any of you can imagine. I pray for the Lord's benediction to rest on my wretched countrymen. My work is finished. My poet is dead.

God will help me, I trust, to rid myself of any desire to follow the example of the other two characters in this work. I shall continue to exist. I may assume other disguises, other forms, but I shall try to exist. I may turn up yet, on another campus, as an old, happy, health heterosexual Russian, a writer in exile, sans fame, sans future, sans audience, sans anything but his art. I may join forces with Odon in a new motion picture: Escape from Zembla (ball in the palace, bomb in the palace square). I may pander to the simple tastes of theatrical critics and cook up a stage play, an old-fashioned melodrama with three principles: a lunatic who intends to kill an imaginary king, another lunatic who imagines himself to be that king, and a distinguished old poet who stumbles by chance into the line of fire, and perishes in the clash between the two figments. Oh, I may do many things! History permitting, I may sail back to my recovered kingdom, and with a great sob greet the gray coastline and the gleam of a roof in the rain. I may huddle and groan in a madhouse. But whatever happens, wherever the scene is laid, somebody, somewhere, will quietly set out--somebody has already set out, somebody still rather far away is buying a ticket, is boarding a bus, a ship, a plane, has landed, is walking toward a million photographers, and presently he will ring at my door--a bigger, more respectable, more competent Gradus. (note to Line 1000)

Zemblan for “my darling,” minnamin blends mon ami (Fr., my friend) with Mignon, a character in Goethe's Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre (“Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship,” 1795-96), and madamina (It., my dear lady), the first word in the Catalogue Aria sung by Leporello (Don Giovanni’s servant) to Elvira in Act One of Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni (1787):

Madamina, il catalogo è questo

Delle belle che amò il padron mio;

un catalogo egli è che ho fatt'io;

Osservate, leggete con me.

In Italia seicento e quaranta;

In Alemagna duecento e trentuna;

Cento in Francia, in Turchia novantuna;

Ma in Ispagna son già mille e tre...

My dear lady, this is the list

Of the beauties my master has loved,

A list which I have compiled.

Observe, read along with me.

In Italy, six hundred and forty;

In Germany, two hundred and thirty-one;

A hundred in France; in Turkey, ninety-one;

But in Spain already one thousand and three...

Il catalogo è questo brings to mind a catalogue raisonné mentioned by Kinbote when he describes his rented house in New Wye. The Wye is a river in England and Wales. Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour. July 13, 1798 is a poem by Wordsworth.