The characters in VN's story Kartofel'nyi El'f ("The Potato Elf," 1929) include Zita and Arabella, the acrobat sisters:

И в эту ночь, когда, после своего номера, Фред в пальтишке и котелке, почихивая и урча, семенил за кулисами по тусклому коридору,- на вершок открывшаяся дверь внезапно брызнула веселым светом, и два голоса позвали его. Это были Зита и Арабелла, сестры-акробатки, обе полураздетые, смуглые, черноволосые, с длинными синими глазами. В комнате был беспорядок, театральная и трепетная пестрота, запах духов. На подзеркальнике валялись пуховки, гребни, граненый флакон с резиновой грушей, шпильки в коробке из-под шоколада, пурпурно-сальные палочки грима.

Сестры мгновенно оглушили карлика своим лепетом. Они щекотали и тискали Фреда, который, весь надувшись темной кровью, смотрел исподлобья и, как шар, перекатывался между быстрых обнаженных рук, дразнивших его. И когда Арабелла, играя, притянула его к себе и упала на кушетку, Фред почувствовал, что сходит с ума и стал барахтаться и сопеть, вцепившись ей в шею. Откидывая его, она подняла голую руку, он рванулся, скользнул, присосался губами к бритой мышке, к горячей, чуть колючей впадине. Другая, Зита, помирая со смеху, старалась оттащить его за ногу; в ту же минуту со стуком отпахнулась дверь, и, в белом, как мраморе, трико, вошел француз, партнер акробаток. Молча и без злобы он цапнул карлика за шиворот,- только щелкнуло крахмальное крылышко, соскочившее с запонки,- поднял на воздух и, как обезьянку, выбросил его из комнаты. Захлопнулась дверь. Фокусник, бродивший по коридору, успел заметить белый блеск сильной руки и черную фигурку, поджавшую лапки на лету.

That same night, as Fred, after his number, snuffling and grumbling, in bowler and tiny topcoat, was toddling along a dim backstage passage, a door came ajar with a sudden splash of gay light and two voices called him in. It was Zita and Arabella, sister acrobats, both half-undressed, suntanned, black-haired, with elongated blue eyes. A shimmer of theatrical disorder and the fragrance of lotions filled the room. The dressing table was littered with powder puffs, combs, cut-glass atomizers, hairpins in an ex-chocolate box, and rouge sticks.

The two girls instantly deafened Fred with their chatter. They tickled and squeezed the dwarf, who, glowering and empurpled with lust, rolled like a ball in the embrace of the bare-armed teases. Finally, when frolicsome Arabella drew him to her and fell backward upon the couch, Fred lost his head and began to wriggle against her, snorting and clasping her neck. In attempting to push him away, she raised her arm and, slipping under it, he lunged and glued his lips to the hot pricklish hollow of her shaven axilla. The other girl, weak with laughter, tried in vain to drag him off by his legs. At that moment the door banged open, and the French partner of the two aerialists came into the room wearing marble-white tights. Silently, without any resentment, he grabbed the dwarf by the scruff of the neck (all you heard was the snap of Fred's wing collar as one side broke loose from the stud), lifted him in the air, and threw him out like a monkey. The door slammed. Shock, who happened to be wandering past, managed to catch a glimpse of the marble-bright arm and of a black little figure with feet retracted in flight. (chapter 2)

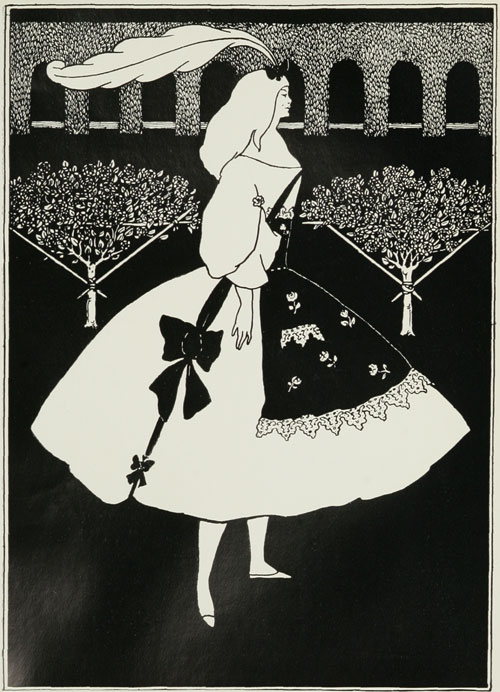

A circus dwarf, Fred Dobson (the Potato Elf) attempts to kiss Arabella's armpit but is thrown away by the Frenchman (Zita's and Arabella's partner). According to Aubrey Beardlsley (the author of The Slippers of Cinderella, one of the six drawings that appeared in Volume II of The Yellow Book, July 1894), Arabella was the name of Cinderella's elder sister:

For you must have all heard of the Princess Cinderella with her slim feet and shining slippers. She was beloved by Prince ——, who married her, but she died soon afterwards, poisoned (according to Dr. Gerschovius) by her elder sister Arabella, with powdered glass. It was ground I suspect from those very slippers she danced in at the famous ball. For the slippers of Cinderella have never been found since. They are not at Cluny.

Hector Sandus

Aubrey Beardsley. The Slippers of Cinderella (The Yellow Book, vol. 2, 1894, p. 95)

In the same Volume II of The Yellow Book Max Beerbohm's Letter to the Editor was published. An English essayist, parodist and caricaturist, Max Beerbohm (1872-1956) is the author of Zuleika Dobson (1911), a novel. A satire of undergraduate life at Oxford, it includes the famous line "Death cancels all engagements." Zuleika Dobson—"though not strictly beautiful"—is a devastatingly attractive young woman of the Edwardian era, a true femme fatale, who is a prestidigitator by profession, formerly a governess. Prestidigitator means conjuror. The characters in The Potato Elf include the conjuror Shock (who gets an engagement in America) and his wife Nora (who seduces the poor dwarf). Fred cannot detach the the gaze of his eyes from the emerald-green pompon on Nora's slipper:

Почувствовав у себя на волосах ее шевелившиеся пальцы, карлик застыл и вдруг начал молча и быстро облизываться. Скосив глаза в сторону, он не мог оторвать взгляд от изумрудного помпона на туфле госпожи Шок. И внезапно каким-то нелепым и упоительным образом все пришло в движение.

Upon feeling those light fingers in his hair, Fred at first sat motionless, then began to lick his lips in feverish silence. His eyes, turned askance, could not detach their gaze from the green pompon on Mrs. Shock’s slipper. And all at once, in some absurd and intoxicating way, everything came into motion. (Chapter 4)

Nora Helmer is the main character in Henrik Ibsen's play A Doll's House (1879). In his Letter to the Editor Max Beerbohm mentions the dulness of Ibsen:

In fact, the police-constable mode of criticism is a failure. True that, here and there, much beautiful work of the kind has been done. In the old, old Quarterlies is many a slashing review, that, however absurd it be as criticism, we can hardly wish unwritten. In the National Observer, before its reformation, were countless fine examples of the cavilling method. The paper was rowdy, venomous and insincere. There was libel in every line of it. It roared with the lambs and bleated with the lions. It was a disgrace to journalism and a glory to literature. I think of it often with tears and desiderium. But the men who wrote these things stand upon a very different plane to the men employed as critics by the press of Great Britain. These must be judged, not by their workmanship, which is naught, but by the spirit that animates them and the consequence of their efforts. If only they could learn that it is for the critic to seek after beauty and to try to interpret it to others, if only they would give over their eternal fault-finding and not presume to interfere with the artist at his work, then with an equally small amount of ability our pressmen might do nearly as much good as they have hitherto done harm. Why should they regard writers with such enmity? The average pressman, reviewing a book of stories or of poems by an unknown writer, seems not to think where are the beauties of this work that I may praise them, and by my praise quicken the sense of beauty in others? He steadily applies himself to the ignoble task of plucking out and gloating over its defects. It is a pity that critics should show so little sympathy with writers, and curious when we consider that most of them tried to be writers themselves, once. Every new school that has come into the world, every new writer who has brought with him a new mode, they have rudely persecuted. The dulness of Ibsen, the obscurity of Meredith, the horrors of Zola—all these are household words. It is not until the pack has yelled itself hoarse that the level voice of justice is heard in praise. To pretend that no generation is capable of gauging the greatness of its own artists is the merest bauble-tit. Were it not for the accursed abuse of their function by the great body of critics, no poet need live uncrown'd, apart. Many and irreparable are the wrongs that our critics have done. At length let them repent with ashes upon their heads. Where they see not beauty, let them be silent, reverently feeling that it may yet be there, and train their dull senses in quest of it. (The Yellow Book, vol. II, 1894, pp. 282-283)